Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa: La Herencia De Livingstone En a Burnt-Out Case, De Graham Greene Y El Sueño Del Celta, De Mario Vargas Llosa

ISSN: 0213-1854 'Civilizar' Africa: La herencia de Livingstone en A Burnt-Out Case, de Graham Greene y El sueño del celta, de Mario Vargas Llosa (‘Civilizing’ Africa: Livingstone’s Inheritance in A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene and El sueño del celta, by Mario Vargas Llosa) BEATRIZ VALVERDE JIMÉNEZ [email protected] Universidad Loyola Andalucía Fecha de recepción: 8 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de julio de 2015 Resumen: En este artículo usamos el concepto de „semiosfera‟ desarrollado por el estudioso ruso-estonio Juri Lotman para examinar las relaciones entre las comunidades nativas y las europeas en el Congo belga creadas por Graham Greene en A Burnt-Out Case y por Mario Vargas Llosa en El sueño del celta. Con este análisis tratamos de probar que aunque ambos autores denuncian con sus obras las terribles consecuencias de la colonización europea para los africanos, las comunidades nativas son descritas desde un punto de vista occidental y paternalista. Palabras clave: Congo. Colonización. Lotman. Semiosfera. Europeos. Africanos. Greene. Vargas Llosa. Abstract: In this article the concept of „semiosphere‟, developed by the Russian-Estonian scholar Juri Lotman, is used to examine the relationship between the African and the European communities in the Congo portrayed by Graham Greene in A Burnt-Out Case and by Mario Vargas Llosa in El sueño del celta. With this analysis I will prove that even though both authors denounce the terrible consequences of the European colonization had for the African people, the native communities in the novels are still depicted from a western paternalistic perspective. -

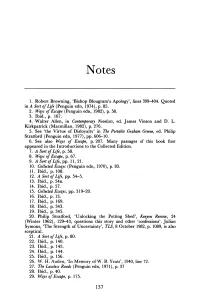

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

The Third Man"

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

Henry Graham Greene Was Born on October 2, 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire

Henry Graham Greene was born on October 2, 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. His father Charles Henry was headmaster of the private school Graham attended. The fourth of six children, Greene was very shy and sensitive. He disliked sports and was often truant from school in order to read adventure stories by authors such as Rider Haggard and Ballantyne. These novels had a deep influence on him and helped to shape his writing style. Greene was educated at Berkhamstead School and Balliol College, Oxford. He had a natural talent for writing, worked for the Times of London and published lots of poems, stories, articles and reviews. In 1927 he married Vivien Dayrell-Browning. After the collapse of their marriage he had several relationships. During World War II Greene worked for the Foreign Office in London. Greene died in Vevey, Switzerland, on April 3, 1991. Graham Greene is an English novelist, short-story writer and journalist, whose novels treat moral issues in the context of political settings. Greene is one of the most read novelist of the 20th-century, an excellent storyteller. Adventure and suspense are constant elements in his novels and many of his books have been made into successful films. Greene was a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature several times, but he never received the award. The Quiet American is set in Vietnam 1952, during the end of the French occupation and start of the American involvement. Thomas Fowler, a foreign correspondent for a newspaper in London, who is living there starts feeling comfortable at his new location, although he has to report stories of the war between the French army and the Communists in Vietnam. -

Denying the Gods: the Religious Roots of Atheism RE230C-002

Denying the Gods: The Religious Roots of Atheism RE230C-002 Instructor: W. Ezekiel Goggin Office: Ladd 210 Email: [email protected] Class Meetings: W/F 8:40-10:00 (Tisch 301) Office hours: WF 10:15-11:45am Course Description A historical and systematic investigation of the religious sources of ancient, modern, and contemporary atheisms. “New Atheists” such as Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, and the late Christopher Hitchens are often invoked in contemporary discourse as intellectually authoritative voices for atheism. For these “New Atheists,” the difference between religion and unbelief is straightforward: rationality is superior to superstition, freedom should be valued over submission, critical inquiry should replace blind faith. However, the historical relationship of atheism to religion and religious belief is considerably more complex than such neat, binary oppositions allow. Far from being a contemporary phenomenon, atheism has religious roots as deep and ancient as the theism which it purports to reject. While “New Atheism” tends to be dismissive of religion and religious beliefs, many ancient and modern atheisms emerged from a willingness to take religion seriously on its own terms. Through comparative analysis of the appearance of atheism and antireligious thought within, between, and adjacent to several religious traditions (e.g., Ancient Greek religion Christian Mysticism, Hinduism, and Judaism), this course will contextualize and evaluate a range of atheistic positions. By the end of the course, we will see, it is perhaps better to speak about “atheisms” than “atheism.” Objectives In pursuit of these themes, students will achieve five major objectives: 1.) Think critically about atheisms within the hermeneutic frameworks of religious studies 2.) Gain familiarity with key theoretical and historical questions and figures in the history of atheism 3.) Develop an appreciation of the complex historical relationship between religions and the atheisms to which they give rise. -

An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Abstract

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Nicholls, Nicole (2014). Engaging Men, An Exploration of the Help-Seeking Experiences of Male Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the draft version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/3749/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Engaging Men, An Exploration of the Help-Seeking Experiences of Male Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse By Nicole Nicholls Thesis submitted to fulfil the requirements of the Professional Doctorate in Counselling Psychology City University Department of Psychology Submitted February 2014 0 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... -

![Concordia Seminary Library, St. Louis Page 1 New Book List As of 4/19/2011 B-BJ [PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOLOGY, ETHICS]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8534/concordia-seminary-library-st-louis-page-1-new-book-list-as-of-4-19-2011-b-bj-philosophy-psychology-ethics-1598534.webp)

Concordia Seminary Library, St. Louis Page 1 New Book List As of 4/19/2011 B-BJ [PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOLOGY, ETHICS]

Concordia Seminary Library, St. Louis Page 1 New Book List as of 4/19/2011 B-BJ [PHILOSOPHY, PSYCHOLOGY, ETHICS] Panigrahy, P. K. The theory of zero-existence : Mãyã, the power divine. New Delhi : Sarup & Sons, 2002. (cosl B132.M3 P35 2002) The Cambridge companion to Philo. Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2009. (cosl B689.Z7 C36 2009) Heyder, Regina, 1966-. Auctoritas scripturae : Schriftauslegung und Theologieverständnis Peter Abaelards unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der "Expositio in Hexaemeron". Münster : Aschendorff, c2010. (cosl B720 .B4 n.F. v.74) Manegold, von Lautenbach, ca. 1030-ca. 1112. Liber contra Wolfelmum. Paris ; Dudley, Mass. : Peeters, 2002. (cosl B734 .M3513 2002) Scepticism from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Wiesbaden : In Kommission bei O. Harrassowitz, 1987. (cosl B779 .S3 1987) Erasmus of Rotterdam Society yearbook. Oxon Hill, Md. : The Society, c1981- (cosl B785.E64 A13) Die deutschen Humanisten : Dokumente zur Überlieferung der antiken und mittelalterlichen Literatur in der frühen Neuzeit. Turnhout : Brepols, 2005- (cosl B821 .D493) Humanismus und Reformation : Martin Luther und Erasmus von Rotterdam in den Konflikten ihrer Zeit. Munchen : Verlag Schnell & Steiner, 1985. (cosl B821 .H87 1985) McDowell, John Henry. Perception as a capacity for knowledge. Milwaukee, Wis. : Marquette University Press, 2011. (cosl B828.45 .M43 2011) Scruton, Roger. The uses of pessimism and the danger of false hope. Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press, 2010. (cosl B1649.S2473 U83 2010) Heidegger, Martin, 1889-1976. Seminare Hegel-Schelling. Frankfurt am Main : Vittorio Klostermann, c2011. (cosl B3279 .H45 1976 v.86) Why Kierkegaard matters : a festschrift in honor of Robert L. Perkins. Macon, Ga. : Mercer University Press, 2010. -

Women Adrift: Familial and Cultural Alienation in the Personal Narratives of Francophone Women

WOMEN ADRIFT: FAMILIAL AND CULTURAL ALIENATION IN THE PERSONAL NARRATIVES OF FRANCOPHONE WOMEN by KAREN BETH MASTERS submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in the subject French at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF. EDGARD SIENAERT, Research fellow, Centre for Africa Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa November 2015 © University of South Africa 2015 ABSTRACT This study analyzes the experience of alienation from family and culture as portrayed in the personal narratives of francophone women. The authors appearing in this study are Assia Djebar and Marie Cardinal, from Algeria, Mariama Bâ and Ken Bugul, from Senegal, Marguerite Duras and Kim Lefèvre, from Vietnam, Calixthe Beyala, from Cameroon, Gabrielle Roy, from Canada, and Maryse Condé, from Guadeloupe. Alienation is deconstructed into the domains of blood, money, land, religion, education and history. The authors’ experiences of alienation in each domain are classified according to severity and cultural normativity. The study seeks to determine the manner in which alienation manifests in each domain, and to identify factors which aid or hinder recovery. Alienation in the domain of blood occurs as a result of warfare, illness, racism, ancestral trauma, and the rites of passage of menarche, loss of virginity, and menopause. Money-related alienation is linked to endemic classism, often caused by colonial influence. The authors experienced varying degrees of economic vulnerability to men, depending upon cultural and familial norms. Colonialism, warfare and environmental degradation all contribute to alienation in the domain of land. Women were found to be more susceptible to alienation in the domain of religion due to patriarchal religious constructs.