Graham Greene's Books for Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa: La Herencia De Livingstone En a Burnt-Out Case, De Graham Greene Y El Sueño Del Celta, De Mario Vargas Llosa

ISSN: 0213-1854 'Civilizar' Africa: La herencia de Livingstone en A Burnt-Out Case, de Graham Greene y El sueño del celta, de Mario Vargas Llosa (‘Civilizing’ Africa: Livingstone’s Inheritance in A Burnt-Out Case, by Graham Greene and El sueño del celta, by Mario Vargas Llosa) BEATRIZ VALVERDE JIMÉNEZ [email protected] Universidad Loyola Andalucía Fecha de recepción: 8 de mayo de 2015 Fecha de aceptación: 1 de julio de 2015 Resumen: En este artículo usamos el concepto de „semiosfera‟ desarrollado por el estudioso ruso-estonio Juri Lotman para examinar las relaciones entre las comunidades nativas y las europeas en el Congo belga creadas por Graham Greene en A Burnt-Out Case y por Mario Vargas Llosa en El sueño del celta. Con este análisis tratamos de probar que aunque ambos autores denuncian con sus obras las terribles consecuencias de la colonización europea para los africanos, las comunidades nativas son descritas desde un punto de vista occidental y paternalista. Palabras clave: Congo. Colonización. Lotman. Semiosfera. Europeos. Africanos. Greene. Vargas Llosa. Abstract: In this article the concept of „semiosphere‟, developed by the Russian-Estonian scholar Juri Lotman, is used to examine the relationship between the African and the European communities in the Congo portrayed by Graham Greene in A Burnt-Out Case and by Mario Vargas Llosa in El sueño del celta. With this analysis I will prove that even though both authors denounce the terrible consequences of the European colonization had for the African people, the native communities in the novels are still depicted from a western paternalistic perspective. -

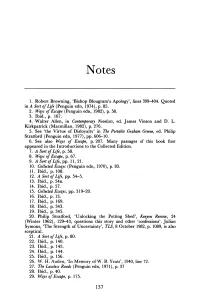

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

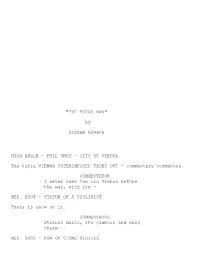

The Third Man"

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Edward Ardizzone Papers, 1935-1966

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1w1004hc No online items Finding Aid for the Edward Ardizzone Papers, 1935-1966 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities --Book ArtsArts and Humanities --Fine Arts --DrawingArts and Humanities --Fine Arts --PaintingGeographical (By Place) --Europe --United Kingdom Finding Aid for the Edward 268 1 Ardizzone Papers, 1935-1966 Finding Aid for the Edward Ardizzone Papers, 1935-1966 Collection number: 268 UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Los Angeles, CA Contact Information UCLA Library Special Collections staff UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Phyllis Herzog, 7 July 1965 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, May 2002 © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Edward Ardizzone Papers, Date (inclusive): 1935-1966 Collection number: 268 Creator: Ardizzone, Edward, 1900- Extent: 1 box (0.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Edward Ardizzone (1900-1979) was born in Haiphong, French Indochina. -

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) - Not Even Past

The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 0 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene (2003) Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the by Mathew J. Butler Confederacy” Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory (1940), the story of a fugitive “whisky priest” in 1930s Mexico, is a short, pathos-laden novel about religious persecution after the Mexican Revolution. The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices. May 06, 2020 Not all professional historians admire the novel, More from The Public Historian however. Some find it overly polemical, others even anachronistic, given that the story of a persecuted priest, written after Greene’s visit in March-April 1938, BOOKS coincided with President Cárdenas’s decision to end the long revolutionary campaign against the Church. It America for Americans: A History of is also rather curious that the most celebrated novel Xenophobia in the United States by about Mexican Catholicism during the Revolution was Erika Lee (2019) written by an English neophyte who was new to Mexico. Greene’s English prejudices give rise to the novel’s flaws. -

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene's 'Dark and Magical Heart

Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ by Dorcas Wangui MA (Lancaster) BA (Lancaster) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Wangui 1 Abstract Visual Theologies in Graham Greene’s ‘Dark and Magical Heart of Faith’ This study explores the ways in which Catholic images, statues, and icons haunt the fictional, spiritual wasteland of Greene’s writing, nicknamed ‘Greeneland’. It is also prompted by a real space, discovered by Greene during his 1938 trip to Mexico, which was subsequently fictionalised in The Power and the Glory (1940), and which he described as ‘a short cut to the dark and magical heart of faith’. This is a space in which modern notions of disenchantment meets a primal need for magic – or the miraculous – and where the presentation of concepts like ‘salvation’ are defamiliarised as savage processes that test humanity. This brutal nature of faith is reflected in the pagan aesthetics of Greeneland which focus on the macabre and heretical images of Christianity and how for Greene, these images magically transform the darkness of doubt into desperate redemption. As an amateur spy, playwright and screen writer Greene’s visual imagination was a strength to his work and this study will focus on how the visuality of Greene’s faith remains in dialogue with debates concerning the ‘liquidation of religion’ in society, as presented by Graham Ward. The thesis places Greene’s work in dialogue with other Catholic novelists and filmmakers, particularly in relation to their own visual-religious aesthetics, such as Martin Scorsese and David Lodge. -

The Destructors Graham Greene

The Destructors Graham Greene Online Information For the online version of BookRags' The Destructors Premium Study Guide, including complete copyright information, please visit: http://www.bookrags.com/studyguide-destructors/ Copyright Information ©2000-2007 BookRags, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. The following sections of this BookRags Premium Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. ©1998-2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". © 1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copywritten by BookRags, Inc. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Annual Report 2009

Annual Report 2009 Digitization INNOVATION CultureFREEDOM CommitmentChange Bertelsmann Annual Report 2009 CreativityEntertainment High-quality journalism Performance Services Independence ResponsibilityFlexibility BESTSELLERS ENTREPRENEURSHIP InternationalityValues Inspiration Sales expertise Continuity Media PartnershipQUALITY PublishingCitizenship companies Tradition Future Strong roots are essential for a company to prosper and grow. Bertelsmann’s roots go back to 1835, when Carl Bertelsmann, a printer and bookbinder, founded C. Bertelsmann Verlag. Over the past 175 years, what began as a small Protestant Christian publishing house has grown into a leading global media and services group. As media and communication channels, technology and customer needs have changed over the years, Bertelsmann has modifi ed its products, brands and services, without losing its corporate identity. In 2010, Bertelsmann is celebrating its 175-year history of entrepreneurship, creativity, corporate responsibility and partnership, values that shape our identity and equip us well to meet the challenges of the future. This anniver- sary, accordingly, is being celebrated under the heading “175 Years of Bertelsmann – The Legacy for Our Future.” Bertelsmann at a Glance Key Figures (IFRS) in € millions 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 Business Development Consolidated revenues 15,364 16,249 16,191 19,297 17,890 Operating EBIT 1,424 1,575 1,717 1,867 1,610 Operating EBITDA 2,003 2,138 2,292 2,548 2,274 Return on sales in percent1) 9.3 9.7 10.6 9.7 9.0 Bertelsmann Value -

Bertelsmann 2018 Summary Plan Descriptions

2 018 Summary Plan Descriptions TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................... CHAPTER General and Administrative Information .......................................................................... Introduction Medical Plans ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Medical Coverage During Retirement ................................................................................. 1A Dental Plans ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Vision Plan................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Disability Plan ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Life and Accident Insurance Plans.......................................................................................... 5 Health Care Flexible Spending Account Plan .......................................................... 6 Dependent Care Flexible Spending Account Plan ............................................ 7 Long Term Care................................................................................................................................................. -

Edward Ardizzone: Artist and Illustrator Free

FREE EDWARD ARDIZZONE: ARTIST AND ILLUSTRATOR PDF Alan Powers | 208 pages | 01 May 2017 | Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd | 9781848221826 | English | London, United Kingdom Edward Ardizzone - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. Overview Edward Ardizzone RA was one of relatively few British artists who defined the field of illustration for their generation. Although his work as an artist and illustrator was wide-ranging, it is for his illustrated children's books, almost continuously available since they were first published from the late s onwards, that he is best known. This book provides the first fully illustrated survey of Ardizzone's work, analysing his activity as an artist and illustrator in the context of 20th- century British art, illustration, printing and publishing. Copiously illustrated with many previously unpublished images, Edward Ardizzone: Artist and Illustrator also contributes more broadly to the Edward Ardizzone: Artist and Illustrator reassessment and investigation of midth-century British art Edward Ardizzone: Artist and Illustrator illustration. Alan Powers author of the bestselling Eric Ravilious: Artist and Designer has written a critically considered text which draws for the first time on the family's archives, those of Ardizzone's publishers, and conversations with those who knew the artist. -

A Critical Analysis of the Priest in the Power and the Glory by Graham Greene

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 5, Issue 4, April 2017, PP 1-11 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0504001 www.arcjournals.org A Critical Analysis of the Priest in the Power and the Glory by Graham Greene Mathias Adandé Mehounou, Marcellin Abadame, Gerard Adounsiba Benin Abstract: In this article, I have sought to analyse the character of the whiskey priest in his painful and desperate quest for repentance. This quest, at first unsatisfied, urges him on fleeing away because of his rejection of the story of his rejection of the moral values which govern the world in which he lives. The story of the whiskey priest in The Power and the Glory can also be seen as the one of a man who suffers like Jesus Christ on the Way of the Cross, from human beings and from Nature. The consequence in that he goes through a moral growth in the sense that, in the end, he proves himself to be modest, compassionate in disrupting the lieutenant‟s habitual way of looking at the Catholic clergy. Keywords: Martyr, Roman Catholic Church, whiskey priest, Judas, mestizo, damnation, sinful. 1. INTRODUCTION The Power and the Glory tells the story of a Roman Catholic priest in the state of Tabasco in Mixico during the 1930s a time when the Mexican government, still effectively controlled by Plutarco Elias Calles, strove to suppress the Catholic Church. The persecution was especially severe in the province of Tabasco, where the atheist governor Tomàs Garrido Canabal had founded and actively encouraged fascist paramilitary groupe called the” Red-Shirts” The main character in the story is a nameless “whiskey priest”, who combines a geat power for self- destruction with pitiful craveness, an almost painful penitence and a desperate quest for dignity.