Rihc Ana Llorente Y Vogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA KIT T Able of Contents

MEDIA KIT T able of Contents 3 About • Seyie Design 4 Interior Branding Services • Hospitality / Residential • Design 360 10 Additional Scope of Services 11 Portfolio - Additional Projects 19 Press • Vogue India • GRAMMY Awards® • ET, Maria Shriver & Coveteur • Vogue & Fendi Casa 23 Contact Information seyiedesign.com 323.630.1841 [email protected] 2 bout A SEYIE DESIGN Seyie Putsure founded Seyie Design to create fashionable & functional branded interiors for luxury and design-conscious residential and beauty, fashion & lifestyle companies. Having started her career as an executive with Saks Fifth Avenue, Chanel and Dolce & Gabbana in New York City, she brings a deep understanding of branding, merchandising and special consumer experience strategy, and a high level of sophistication into the interiors that Seyie Design creates. Since its founding in 2007, Seyie Design’s body of work has grown internationally to include corporate offce, mixed-use development, retail, high-end salons and spas, boutique bakeries, event lounges and private residences. Seyie was Fendi Casa’s Designer of the Month, the exclusive designer for the 54th and 55th Annual GRAMMY Awards® Offcial Talent Gift Lounge, and has been featured in TIME, LUCKY, Vogue, Elle, and DDI Magazine, among others. She has also been named by Vogue India as one of “the new women of interiors.” Understanding an individual’s personal style or a company’s brand image, along with their unique lifestyle or practical business needs, Seyie Design works directly with clients on all levels to discover the best harmony for spaces from concept to execution. It balances fashionable interiors that capture the essence of the individual or company’s brand identity, and functional spaces that support lifestyle or promote business productivity. -

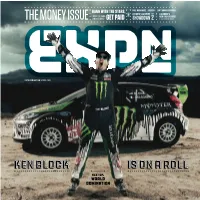

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Depictions of Empowerment? How Indian Women Are Represented in Vogue India and India Today Woman a PROJECT SUBMITTED to the FACU

Depictions of Empowerment? How Indian Women Are Represented in Vogue India and India Today Woman A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Monica Singh IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES August 2016 © Monica Singh, 2016 Contents ILLUSTRATIONS........................................................................................................................ ii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................................................................ 19 CHAPTER 3 ................................................................................................................................ 28 CHAPTER 4 ................................................................................................................................ 36 CHAPTER 5 ................................................................................................................................ 53 CHAPTER 6 ................................................................................................................................ 60 REFLECTION FOR ACTION................................................................................................. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

Who's Pulling the Strings?

UNITED STATE DUNHILL REVS UP OF MIND THE LABEL’S A BUOYANT NEW SCENT, AMERICAN MARKET WAS ICON, IS SET A KEY TOPIC AT THE PITTI THE DRESS RACE IS ON TO LAUNCH IMMAGINE UOMO TRADE WITH THE OSCAR NOMINEES SET, THE FOCUS MONDAY. SHOW. PAGES 4 AND 5 TURNS TO WHO WILL WEAR WHAT. PAGE 11 PAGE 7 WWDFRIDAY, JANUARY 16, 2015 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY END OF AN ERROR Target Exiting Canada, Court OKs Liquidation “I came hoping to fi nd a path By SHARON EDELSON that would allow us to continue operations in Canada,” Cornell BRIAN CORNELL CONTINUES said during a conference call with to shake things up at Target. retail analysts on Thursday. “My The retailer on Thursday de- strong preference was to develop a cided to end its money-losing plan to fulfi ll that vision. I realized business in Canada and received the solution would not be easy.” permission from a Canadian Cornell said that when he realized court to begin the liquidation the extent to which Target had process, including the appoint- disappointed Canadian consum- ment of Alvarez & Marsal Canada, ers, he decided the problems were under the Companies’ Creditors insurmountable. Target will close Arrangement Act. 133 stores, which will result in a When Cornell joined Target loss of about 17,600 jobs. Corp. as chairman and chief execu- Target’s entry into Canada tive offi cer in August, he promised began in 2011, when it acquired employees and shareholders that 220 Zellers leases from Hudson’s he would take a “good, hard look at Bay Co. -

ANNUAL Report 2011

ANNUAL REPORT REPORT annual 2011 2011 Incorporated in France as a “Société Anonyme” with registered capital of 120,596,816.40 euros 632 012 100 R.C.S. Paris Headquarters: 41 rue Martre 92117 Clichy – France Tel.: +33 1 47 56 70 00 Fax: +33 1 47 56 86 42 Registered office: 14 rue Royale 75008 Paris – France www.loreal.com www.loreal-finance.com YOUR CONTACTS INDIVIDUAL SHAREHOLDERS AND FINANCIAL ANALYSTS AND FINANCIAL MARKET AUTHORITIES INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS Jean Régis Carof Françoise Lauvin [email protected] Tel.: +33 1 47 56 86 82 [email protected] Carolien Renaud-Feitz [email protected] Investors Relations Department L’Oréal Headquarters From France: toll-free number for 41, rue Martre shareholders: 0 800 666 666 92117 Clichy Cedex – France From outside France: +33 1 40 14 80 50 JOURNALISTS Service Actionnaires L’Oréal Corporate Media Relations BNP Paribas Securities Services Stéphanie Carson Parker Service Emetteurs Tel.: +33 1 47 56 76 71 Grands Moulins de Pantin [email protected] 9, rue du Débarcadère 93761 Pantin Cedex – France Corporate Media Relations L’Oréal Headquarters 41, rue Martre 92117 Clichy Cedex – France Published by the Administration and Finance Division and by the Image and Corporate Information Department. This is a free translation into English of the L’Oréal 2011 Annual Report issued in the French language and is provided solely for the convenience of English speaking readers. In case of discrepancy the French version prevail. Photograph credits: Josemar Alves (p.57), Syed Muhammad Anas (p.17, 51), Chung Anh (p.57, 70), David Arky/Tetra Images/GraphicObsession/ Photononstop (p.66), David Arraez (p.57), Leandro Bergamo (p.9, 21, 46, 63), Jean-Christian Bourcart/Interlinks Image (p.17), Anthony Bradshaw/ Getty Images (p.55), Alain Buu (p.11, 79), Stéphane Coutelle/D. -

2018 Pulse of the Fashion Industry

PULSE OF THE FASHION INDUSTRY 2018 PULSE OF THE FASHION INDUSTRY 2018 Publisher Acknowledgements Global Fashion Agenda and The Boston Consulting Group The authors would like to thank all of those who contributed their time and expertise to this report. Authors Morten Lehmann, Sofia Tärneberg, Thomas Special thanks go to the Sustainable Apparel Coalition for providing Tochtermann, Caroline Chalmer, Jonas Eder-Hansen, the data that made it possible to take the Pulse of the Fashion Dr. Javier F. Seara, Sebastian Boger, Catharina Hase, Industry, and the colleagues who contributed to this report, including Viola Von Berlepsch and Samuel Deichmann Baptiste Carrière-Pradal, Jason Kibbey, and Elena Kocherovsky. Copywriter Global Fashion Agenda Strategic Partners: Christine Hall and John Landry Hendrik Alpen (H&M), Michael Beutler (Kering), Mattias Bodin (H&M), Cecilia Brännsten (H&M), Baptiste Carriere-Pradal (Sustainable Graphic Designer Apparel Coalition), Helen Crowley (Kering), Marie-Claire Daveu Daniel Siim (Kering), Sandra Durrant (Target), Anna Gedda (H&M), Emilio Guzman (H&M), Jason Kibbey (Sustainable Apparel Coalition), Ebba Larsson Cover photo (H&M), Maritha Lorentzon (H&M), Ivanka Mamic (Target), Pamela Global Fashion Agenda Mar (Li & Fung), Emmanuelle Picard-Deyme (Kering), Dorte Rye Olsen (BESTSELLER), Harsh Saini (Li & Fung), Dorthe Scherling Nielsen Photos (BESTSELLER), Cecilia Takayama (Kering), Cecilia Tiblad Berntsson Copenhagen Fashion Week (H&M) and Géraldine Vallejo (Kering). Simon Lau I:CO/ SOEX Group Global Fashion Agenda Sounding Board: Orsola de Castro (Fashion Revolution), Simone Cipriani (Ethical Print Fashion Initiative), Linda Greer (NRDC), Katrin Ley (Fashion for Good) KLS PurePrint A/S and Bandana Tewari (Vogue India). 2018 Copyright © Global Fashion Agenda and Global Fashion Agenda team: The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. -

Title List of Rbdigital Magazine Subscriptions (May27, 2020)

Title List of RBdigital Magazine Subscriptions (May27, 2020) TITLE SUBJECT LANGUAGE PLACE OF PUBLICATION 7 Jours News & General Interest FrencH Canada AD – France Architecture FrencH France AD – Italia Architecture Italian Italy AD – GerMany Architecture GerMan GerMany Advocate Lifestyle EnglisH United States Adweek Business EnglisH United States Affaires Plus (A+) Business FrencH Canada All About History History EnglisH United KingdoM Allure WoMen EnglisH United States American Craft Crafts & Hobbies EnglisH United States American History History EnglisH United States American Poetry Review Literature & Writing EnglisH United States American Theatre Theatre EnglisH United States Aperture Art & Photography EnglisH United States Apple Magazine Computers EnglisH United States Architectural Digest Architecture EnglisH United States Architectural Digest - India Architecture EnglisH India Architectural Digest - MeXico Architecture SpanisH MeXico Art & Décoration - France HoMe & Lifestyle FrencH France Artist’s Magazine Art & Photography EnglisH United States Astronomy Science & TecHnology EnglisH United States Audubon Magazine Science & TecHnology EnglisH United States Australian Knitting Crafts & Hobbies EnglisH Australia Avantages HS HoMe & Lifestyle FrencH France AZURE HoMe & Lifestyle EnglisH Canada Backpacker Sports & Recreation EnglisH United States Bake from ScratcH Food & Beverage EnglisH United States BBC Easycook Food & Beverage EnglisH United KingdoM BBC Good Food Magazine Food & Beverage EnglisH United KingdoM BBC History Magazine -

Fotografi 105 NOK

Nummer 2 2021 Fotografi 105 NOK Mikael Jansson Aapo Huhta Terje Abusdal K. Linnea Backe Lisa Digernes Tina Modotti Kyrre Lien Morten Løberg TIDSAM 2611-02 02 7 388261 110502 RETURUKENummer 19 2 — 2021 1 Innhold 7 Aktuelt 12 Mitt utstyr: Mirjam Stenevik 14 Mikael Jansson: Med haukeblikk 30 Mitt viktigste bilde: Monica Strømdahl 32 Aapo Huhta: Et øyeblikk i tiden 44 Fotobøker: Terje Abusdal 50 Lesernes portfolio: K. Linnea Backe 58 Samleren: Lisa Digernes 62 Tema: Karantenekunst 70 Profil: Kyrre Lien 72 Klassikeren: Tina Modotti 78 NFF: Stein Dahlsrud 82 Morten Løberg: Minimalist med bred horisont 96 10 spørsmål: Else Marie Hagen 2 Fotografi «Alt jeg gjør fotografisk er basert på en refleksjon rundt hva som er sant og ikke i et bilde.» – Aapo Huhta Nummer 2 — 2021 3 Leder Et år har nå gått siden Norge stengte ned. Med ett ble hverdagen for fotografer, forhandlere, skoler og studenter snudd på hodet. For mange ble selve livsgrunn- laget revet bort i løpet av noen dager, mens for andre ble utfordringen å finne løsninger som gjorde det praktisk mulig å kunne gjøre et fotoopptak, selge et kamera eller holde en forelesning under de overveldende restriksjonene som har fulgt oss siden mars 2020. Men etter hvert kommer hverdagen krypende. Man finner måter å løse utfor- dringene på, og nye løsninger ser dagens lys. Skolene holder foredrag via nett, studentene finner nye måter å løse oppgavene sine på, og fotografer gjør sine jobber med to meters avstand, antibac og ansiktsmasker. I denne utgaven av Fotografi har vi snakket med en rekke fotografer og spurt dem om hvordan dette året har vært for dem. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm-chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury-fashion businesses Journal Item How to cite: Carrigan, Marylyn; Moraes, Caroline and McEachern, Morven (2013). From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm-chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury-fashion businesses. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(11-12) pp. 1277–1307. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 Westburn Publishers Ltd. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.798675 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk [Referencing details: Carrigan, M., Moraes, C. and McEachern, M. (forthcoming), “From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury fashion businesses,” Journal of Marketing Management.] From conspicuous to considered fashion: A harm chain approach to the responsibilities of luxury fashion businesses Professor Marylyn Carrigan*, Department of Marketing, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham, University House, Birmingham, B15 2TY Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 121 415 8179 Fax: +44 (0) 121 414 7791 *author for correspondence Dr. Caroline Moraes, Department of Marketing, Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham, University House, Birmingham, B15 2TY Dr. Morven McEachern, Department of Marketing, Lancaster University Management School, Charles Carter Building, Lancaster LA1 4YX Author biographies Prof. -

Donna Karan Celebrated the Easy-Pieces Mantra on Which Ample Knits That Covered Cozy from Nordic to Aran to Homespun, the Latter in the Mulleavy She Founded Her House

PLUS HAIDER ACKERMANN SOCIAL MEDIA CRUSH BELLE CURVES MISSING MCQUEEN CHANEL’S ICEBERG ROAD TO TRADITION WWD BYE-BYE, BRYANT PARK COLLECTIONS CARDIN’S SPACE RACE CHRISTOPHER BAILEY Inspector Gadget A Top Ten: John Galliano is RICCARDO TISCI riding high at Givenchy’s Self-Made Man Christian Dior. L’WREN SCOTT Fearlessly Chic THE TRENDS PATCHWORK FUR NORDIC TRACK BLUSH HOUR PLAID TIMES VELVET CRUSH ARMY LIVES AND MORE The Top Ten FALL ’10 Collections 0412.COL.001.Cover.a;15.indd 1 4/6/10 8:42:43 PM You Choose vote for Your favorite designer P o P u L a r vote SPONSORED bY Make your favorite designer a winner at the 2010 CFDA Fashion Awards and be entered for a chance to win tickets to a New York Fashion Week show.* The CFDA Fashion Awards are a production of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. www.cfda.com vote now on *NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. To enter and for full rules, go to www.wwd.com/popular-vote. Starts 9:00 AM EST 4/1/10 and ends 11:59 PM EST 5/28/10. Open to legal residents of the 50 United States/D.C. 18 or older, except employees of Sponsor, their immediate families and those living in the same household. Odds of winning depend on the number of entries received. Void outside the 50 PHOTO BY STEVE EICHNER United States/D.C. and where prohibited. A.R.V. of prize $1,459.99: Sponsor: Condé Nast Publications. You Choose vote for Your favorite designer P o P u L a r vote SPONSORED bY Make your favorite designer a winner at the 2010 CFDA Fashion Awards and be entered for a chance to win tickets to a New York Fashion Week show.* The CFDA Fashion Awards are a production of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. -

Styleline Fallwinter 06.Indd

Philadelphia University Fall/Winter 2005/2006 FASHION WEEK SPRING 2006 Focus on . Alumni “All Dressed Up” Alice Temperley Spring 2006 By Kristen Goldy and By Danielle Badali www.Style.com Kari McElwee every shape and size. his year, the Spring Dresses ranged from gran- W hen mentioning "fash- T2006 fashion shows ny to baby doll, and ion," very often, the industry were every woman’s many were finished is seen as risky. However, dream. From with clean, handker- for Gretchen Miller, a for- Versace’s curve- chief hems. Light mer Fashion Design major at hugging skirts blues, greens and Philadelphia University, and to Temperley’s oranges comple- her partner, Lori Hedrick, an lady-like dresses, mented a satiny but- unconventional slow-and- it's all about being ter-cream shade that steady approach appears to be feminine and pretty. looked as though it the right one. The Trenton, Gretchen Miller (left) and Lori And this season, was drizzled on. To N.J., natives founded Lolo + Hedrick at the grand opening. each designer show- add to the modern Gretch Dahling in 2002, a col- cased a unique way feel, Sui matched lection of uniquely designed funding and exposure. “We’ve to achieve this. dresses and skirts wrist bags characterized by never taken out a big loan or In New York, with western-style patchwork detail and vintage anything,” Hedrick explains, Alice Temperley boots and long feel. Recently, I was able to “we only use the money we brought a delicate rope necklaces. For catch up with the creative make.” This approach certainly splash of lady-like evening, dresses women to discuss their experi- slows expansion; yet Miller elegance to the runway and skirts that ences in the business.