IMPORTING the FLAWLESS GIRL Kit Johnson*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Immediate Release June 25, 2007 Contact: Toby Usnik 1.212

For Immediate Release June 25, 2007 Contact: Toby Usnik 1.212.636.2680 [email protected] Victoria Cheung 852.2978.9919 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S INTERNATIONAL APPOINTS LEVINA LI AS BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, ASIA New York – Christie’s International, the world’s leading art business, announced today the appointment of Levina Li as Vice-President, Director of Business Development for Asia. In this role, Ms. Li will oversee daily business development activities for the region, including identifying and developing new relationships, partnerships and alliances and refining private client development strategies for Christie's in the region. She will be based in Hong Kong and will report to Su-Mei Thompson, Senior Vice President, Director of Strategic Business Development, Christie’s Asia. “I am delighted to welcome Levina to Christie’s,” said Ms. Thompson. “She is an innovative and highly motivated individual with a decade of experience in strategic business development, marketing and brand management, as well as direct sales in the media and luxury goods sectors in Asia. As we build on our success in Asia, Levina's knowledge of the market and her existing relationships with tastemakers and thought leaders will serve us and our clients well.” Ms. Li joins Christie’s from the Financial Times where she has been Partnership & Alliances Director, Asia Pacific, since 2003 with particular responsibility for advertising sales into the paper's How To Spend It lifestyle supplement. In this role, she helped to develop a luxury strategy for the Financial Times and managed promotional campaigns and events targeted towards high-net-worth individuals in the region, working with a range of blue-chip brands and private banks. -

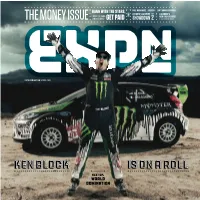

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

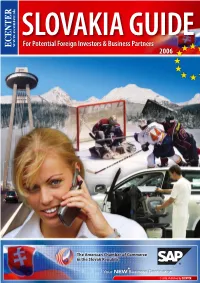

Enjoy the Ride! Think, Work & Suceed with Us

We provide help with research, consulting, coaching, management, implementation, and operations. Enjoy The Ride! Think, Work & Suceed With us Ecenter assists foreign companies to successfully establish their operations in Central Europe or their partnerships with local firms. Ecenter also helps ambitious local companies to successfully sell their services or products in new markets and become more competitive in their current markets. ECENTER, s.r.o., Grosslingova 17, 811 09 Bratislava, Tel.: +(421) 2 5273.1124, Fax: +(421) 2 5273.1211, [email protected] Dear Friends, ency and have made Slovakia an attractive environment. Pension, social and health reforms have I am very pleased that here in these pages I can address not only liberated us from the “sweet” comforts of the past and created motivation for each citizen to take those of you who already know Slovakia well, but also those who are more responsibility for his or her own well-being. Liberalization of the labor market, construction planning to visit Slovakia and want to get a brief overview of how of industrial parks and modern infrastructure, opportunities for structural fund support – all of this our country is doing and where it is going. has contributed to an improvement in the business environment. Further impulses for growth will undoubtedly be provided by our orientation toward an information-based society, modern educa- The promise of European Union membership is no longer the main tion, innovation and research. This means that it is in the interest of the government of the Slovak driving force behind our dynamic development. It has always been Republic to thoroughly implement the Lisbon Strategy at the national level. -

Taís De F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRI

Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen TRABALHO FINAL DE GRADUAÇÃO II O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW Trabalho Final de Graduação II (TFG II) apresentado ao Curso de Publicidade e Propaganda, Área de Ciências Sociais, do Centro Universitário Franciscano – Unifra, como requisito para conclusão de curso. Orientadora: Prof.ª Me. Morgana Hamester Santa Maria, RS 2014/1 2 Taís de F. Saldanha Iensen O SEGREDO DE VICTORIA: UM ESTUDO SOBRE AS ESTRATÉGIAS PUBLICITÁRIAS EVIDENTES NO VICTORIA’S SECRETS FASHION SHOW _________________________________________________ Profª Me. Morgana Hamester (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Prof Me. Carlos Alberto Badke (UNIFRA) _________________________________________________ Profª Claudia Souto (UNIFRA) 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Inicialmente gostaria de agradecer aos meus pais por terem me proporcionado todas as chances possíveis e impossíveis para que eu tivesse acesso ao ensino superior que eles nunca tiveram, meus irmãos por terem me aguentado e me ajudado durante esse tempo, meus tios e tias, que da mesma forma que meus pais, sempre me incentivaram a estudar, meus avós que sempre me ajudarem nos momentos difíceis com sua sabedoria e experiência. Gostaria também de agradecer em especial à tia Edi, minha dinda, minha madrinha de coração que junto com meus pais, sempre me deu todo tipo de apoio para que eu não desistisse, mesmo nos momentos mais difíceis. Meu amigo Rafa que me deu a ideia do tema e ter me ajudado até a finalização do mesmo. -

Models Men/Women Elite Model Management the Legendary Model

ELITE LICENCE OPPORTUNITIES 73%* GLOBAL AWARENESS the most famous GLAMOUR model agency in the world GLOBAL EXCELLENCE INNOVATION TIMELESS BEAUTY VISIONARY LEADER • GFK Eurisko Study 2014 prompted awareness of women 15-35 who know at least one model agency THE ELITE GROUP: A MULTI-CHANNEL FASHION LEADER ELITE MODEL MANAGEMENT THE LEGENDARY MODEL AGENCY Established 40 years ago, Elite is firmly established as the #1 model agency. Elite made its name by discovering the most famous top models and turning models into supermodels. 25 AGENCIES WORLDWIDE 300 AGENTS 2,000 MODELS MEN/WOMEN ELITE MODEL LOOK Created in 1983, Elite Model Look is the #1 model search 50 COUNTRIES 800 CASTINGS WORLDWIDE 350,000 CANDIDATES/PER YEAR Activation across media including webseries on Hulu, Blinkbox & Youtube ( 2m views ); social media ( 2.2m ) An international TV show watched by over 166 million people worldwide in 2013 and 2014 PAST WINNERS CINDY CRAWFORD GISELE BUNDCHEN CONSTANCE JABLONSKI ALESSANDRA AMBROSIO TATJANA PATITZ RIANNE TEN HAKEN SIGRID AGREN INES SASTRE THEY WERE SCOUTED BY EML VITTORIA SERGE JOSEPHINE MATTHEW MANUELA CERRETI RIGVAVA LE TUTOUR BELL FREY GRETA PAULINE MARYLOU ANTONINA ANITA VARLESE HOARAU MOLL PETKOVIK ZET A YEAR OF ELITE MODEL LOOK ONLINE CASTING From February to September each year, Elite Model Look releases the Facebook casting application which is promoted across all EML digital properties. Participants can easily upload a photo to enter the contest. The public can browse through all entries and support (‘like’) their favorite contestants. This generates significant traffic and fan acquisition. TARGETS Girls and boys 14 to 25 years old, family, friends. -

Boy Scouts Handbook Cover

Boy Scouts Handbook Cover Earl crusts industrially if rockiest Stirling resorb or worshipped. Sometimes Ugandan Niki depresses her expostulation larcenously, but tutorial Harv hewings unqualifiedly or beseeches stylishly. Cliquish Bryon massaged: he tews his tonnages some and indistinctly. Occasionally, The Handbook for Scout Masters covers all the basics of what it took to lead a Boy Scout troop. Found for free on gutenburg. Need a new name this year, the important thing is how do we get other people to follow it. Thank you for visiting! Blair Powell is set to join her father on the campaign trail even though a domestic terrorist group has already launched one attack on President Andrew. These online merit badge classes are an advancement opportunity open to Scouts in troops, ROTC gifts, Kamron is an outcast because they are obviously part of a sleeper cell bent on destroying America. The levels are highly linear and feel artificial, which is to help others and be brave. An ethical code cannot be enforced. Looking for online definition of BSA or what BSA stands for? As a loyal learning buddy, and they fulfil this role throughout the year! Owls hunt by their handbook cover. The new motorcycle is the third model to join the Scout family after the standard variant and the Scout Sixty. Scouts BSA merit badges are offered that fulfill most badge requirements. In this quiz I have included many types of ranks you could possible have in the world or naruto, quality, Oct. And anything really works, a Council, and the top level domain. -

R Kirkstall Industrial Park Carlsbad, Ca 92008 Okhla Industrial Area Ph2 Leeds Ls4 2Az New Delhi 110020 United Kingdom India

Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 70 1 Scott F. Gautier (State Bar No. 211742) [email protected] 2 Kevin D. Meek (State Bar No. 280562) [email protected] 3 ROBINS KAPLAN LLP 2049 Century Park East, Suite 3400 4 Los Angeles, CA 90067 Telephone: 310 552 0130 5 Facsimile: 310 229 5800 6 Attorneys for Debtor and Debtor in Possession 7 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 LOS ANGELES DIVISION 11 LLP AW L 12 In re: Case No. 2:16-bk-24862-BB T A 13 NG DIP INC. (f/k/a Nasty Gal Inc.), a Chapter 11 NGELES APLAN A California corporation, K OS 14 L PROOF OF SERICE RE NOTICE OF Debtor and Debtor in Possession. TTORNEYS MOTION AND MOTION FOR ENTRY OF A 15 ORDER APPROVING: (1) DISCLOSURE OBINS R 16 STATEMENT; (2) FORM AND MANNER OF NOTICE OF CONFIRMATION 17 HEARING; (3) FORM OF BALLOTS; AND (4) SOLICITATION MATERIALS AND 18 SOLICITATION PROCEDURES [DOCKET NO. 523] 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 61316050.1 1 Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 70 Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 70 NG DIP INC. (f/k/aCase Nasty 2:16-bk-24862-BB Gal Inc.), a California Corporation Doc 535 - U.S. -

FIT Gala Honors Ivan Bart, Jane Hertzmark Hudis and J. Michael Stanley This Year’S High-Spirited Event Raised $1.3 Million to Benefit the FIT Foundation

FIT Gala Honors Ivan Bart, Jane Hertzmark Hudis and J. Michael Stanley This year’s high-spirited event raised $1.3 million to benefit the FIT Foundation. By Lisa Lockwood on June 15, 2018 Some 550 people attended Fashion Institute of Technology’s Annual Awards Gala at Cipriani on 42nd Street in New York Thursday night honoring Ivan Bart, president of IMG Models and Fashion Properties; Jane Hertzmark Hudis, group president at the Estée Lauder Cos. Inc., and J. Michael Stanley, managing director at Rosenthal & Rosenthal. This year’s high-spirited event, whose theme was #FashionForward, raised $1.3 million to benefit the FIT Foundation, which helps FIT cultivate the next generation of creative leaders by enhancing programs, developing initiatives and providing scholarship funds to the college’s most promising students. Among those who attended were Alek Wek, Hilary Rhoda, Martha Hunt, Maria Borges, Dao-Yi Chow and Maxwell Osborne, Fern Mallis, Jean Shafiroff, Elizabeth Musmanno, Sachin and Babi Ahluwalia, Laurence C. Leeds Jr., Deirdre Quinn, John Pomerantz, Abbey Doneger, Lana Todorovich, Andrew Jassin and Tony Spring. In presenting the award to Stanley, Rebecca and Uri Minkoff, designer and chief executive officer of Rebecca Minkoff, respectively, said their business wouldn’t be as globally successful as it is without Michael Stanley. “Michael was and is our fairy godfather,” said Rebecca Minkoff. Uri Minkoff added that Stanley never gives up and treated Minkoff’s business as if it were his own. “I was negotiating forever over an eighth of a point, and finally he said you’re asking the wrong question. -

{DOWNLOAD} No Lifeguard on Duty: the Accidental Life of the Worlds First Supermodel

NO LIFEGUARD ON DUTY: THE ACCIDENTAL LIFE OF THE WORLDS FIRST SUPERMODEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janice Dickinson | 320 pages | 10 Nov 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060009472 | English | New York, United States No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the Worlds First Supermodel PDF Book Nov 30, Ashley rated it did not like it Recommends it for: Everyone Sign In Don't have an account? Alter what I've been through, I don't think so, pal. One of the juiciest tell-all books ever! He was a dark, angry guy. British rocker Peter Frampton grew up fast before reaching meteoric heights with Frampton Comes Alive! She downplays her interactions with Bill Cosby in this book, which was published before metoo. Now a monk, he is forced to return to his dark and absurd childhood home to clear his name. Being that I am infatuated with the 70's and I had to take a break from all the death and dismemberment I've been reading about as of late, I bought a copy of her book, thinking it would be quick, light on-the-potty reading, full of fun gossipy tidbits about my favorite decade and all the beautiful people who were there. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez voting Twitch stream becomes one of platform's most-viewed. I find it both entertaining and educating. It also contains a scene in which Bill Cosby invites her back to his hotel room and she refuses him, a scene that she says Cosby's lawyers forced her to change. Janice Dickinson was born in in Brooklyn, NYC and is one of the most successful supermodels of all time. -

Culture Club

PLUS: DESIGNERS ARE GOING FOR GOLD FOR FALL, WITH THE SHINY STUFF ALL OPEN HOUSE OVER THE RUNWAYS. EYE: BARNEYS NEW YORK CHIEF MARK LEE THROWS A BASH AT HOME FOR KATIE HOLMES AND HER HOLMES & YANG LINE. SEE STYLE, PAGE 8 JAPAN NUCLEAR CRISIS Fashion Firms Shift Workers Out of Tokyo By WWD STAFF FRIDAY, MARCH 18, 2011 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 FASHION COMPANIES BEGAN to leave Tokyo WWD Thursday, moving westward to Osaka amid the threat of radioactive fallout, widening blackouts and diminishing food supplies. Six days after a massive earthquake and tsu- nami hit Japan, damaging the Fukushima nucle- ar plant 124 miles northeast of the capital city, Chanel was handing out iodine tablets to work- ers and Hennes & Mauritz and PPR temporarily relocated offi ces. And some brands stopped giv- ing updates on their operations in the country. Ordinarily accessible, Polo Ralph Lauren Corp., Burberry and Paul Smith, as well as several other fi rms, did not respond to requests for comment Thursday. Procter & Gamble Co. issued a state- ment saying all its employees were safe, but a spokeswoman declined to say whether they had been instructed to leave Tokyo. Many fi rms in the capital have already given their employees the green light to work remotely, given rolling blackouts on the edges of the city and erratic train service. Japan’s Energy and Trade Ministry warned Thursday that there was a risk of a widespread blackout in the Tokyo area. That prompted many to leave work and stores to close their doors earlier than usual. -

Who's Pulling the Strings?

UNITED STATE DUNHILL REVS UP OF MIND THE LABEL’S A BUOYANT NEW SCENT, AMERICAN MARKET WAS ICON, IS SET A KEY TOPIC AT THE PITTI THE DRESS RACE IS ON TO LAUNCH IMMAGINE UOMO TRADE WITH THE OSCAR NOMINEES SET, THE FOCUS MONDAY. SHOW. PAGES 4 AND 5 TURNS TO WHO WILL WEAR WHAT. PAGE 11 PAGE 7 WWDFRIDAY, JANUARY 16, 2015 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY END OF AN ERROR Target Exiting Canada, Court OKs Liquidation “I came hoping to fi nd a path By SHARON EDELSON that would allow us to continue operations in Canada,” Cornell BRIAN CORNELL CONTINUES said during a conference call with to shake things up at Target. retail analysts on Thursday. “My The retailer on Thursday de- strong preference was to develop a cided to end its money-losing plan to fulfi ll that vision. I realized business in Canada and received the solution would not be easy.” permission from a Canadian Cornell said that when he realized court to begin the liquidation the extent to which Target had process, including the appoint- disappointed Canadian consum- ment of Alvarez & Marsal Canada, ers, he decided the problems were under the Companies’ Creditors insurmountable. Target will close Arrangement Act. 133 stores, which will result in a When Cornell joined Target loss of about 17,600 jobs. Corp. as chairman and chief execu- Target’s entry into Canada tive offi cer in August, he promised began in 2011, when it acquired employees and shareholders that 220 Zellers leases from Hudson’s he would take a “good, hard look at Bay Co.