The Ryukyuanist a Newsletter on Ryukyu/Okinawa Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

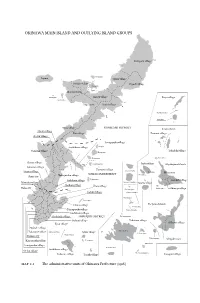

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Higashi Village

We ask for your understanding Cape Hedo and cooperation for the environmental conservation funds. 58 Covered in spreading rich green subtropical forest, the northern part of 70 Okinawa's main island is called“Yanbaru.” Ferns and the broccoli-like 58 Itaji trees grow in abundance, and the moisture that wells up in between Kunigami Village Higashi Convenience Store (FamilyMart) Hentona Okinawa them forms clear streams that enrich the hilly land as they make their way Ie Island Ogimi Village towards the ocean. The rich forest is home to a number of animals that Kouri Island Prefecture cannot be found anywhere else on the planet, including natural monu- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium Higashi Nakijin Village ments and endemic species such as the endangered Okinawa Rail, the (Ocean Expo Park) Genka Shioya Bay Village 9 Takae Okinawan Woodpecker and the Yanbaru Long-Armed Scarab Beetle, Minna Island Yagaji Island 331 Motobu Town 58 Taira making it a cradle of precious flora and fauna. 70 Miyagi Senaga Island Kawata Village With its endless and diverse vegetation, Yanbaru was selected as a 14 Arume Gesashi proposed world natural heritage site in December 2013. Nago City Living alongside this nature, the people of Yanbaru formed little settle- 58 331 ments hugging the coastline. It is said that in days gone by, lumber cut Kyoda I.C. 329 from the forest was passed from settlement to settlement, and carried to Shurijo Castle. Living together with the natural blessings from agriculture Futami Iriguchi Cape Manza and fishing, people's prayers are carried forward to the future even today Ginoza I.C. -

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” Under the Japan-U.S

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” under the Japan-U.S. Alliance August 10-12, 2013 International Geographical Union (IGU) 2013 Kyoto Regional Conference Commission on Political Geography Post-Conference Field Trip In Collaboration with Political Geography Research Group, Human Geographical Society of Japan and Okinawa Geographical Society Contents Organizers and Participants………………………………………………………………………….. p. 2 Co-organizers Assistants Supporting Organizations Informants Participants Time Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 4 Route Maps……………………………………………………………………………………….…..p. 5 Naha Airport……………………………………………………………………………………….... p. 6 Domestic Flight Arrival Procedures Domestic Flight Departure Procedures Departing From Okinawa during a Typhoon Traveling to Okinawa during a Typhoon Accommodation………………………………………...…………………………………………..... p. 9 Deigo Hotel History of Deigo Hotel History of Okinawa (Ryukyu)………………………………………..………………………............. p. 11 From Ryukyu to Okinawa The Battle of Okinawa Postwar Occupation and Administration by the United States Post-Reversion U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa…………………………………………………………………...… p. 14 Futenma Air Station Kadena Air Base Camp Schwab Camp Hansen Military Base Towns in Okinawa………………………………………………………...………….. p. 20 Political Economic Profile of Selected Base Towns Okinawa City (formerly Koza City) Chatan Town Yomitan Village Henoko, Nago City Kin Town What to do in Naha……………………………………………………………………………...… p. 31 1 Organizers -

Page 1 ACTA ARACHNOL., 27, Special Number), 1977. 337

ACTAARACHNOL.,27,Specialnumber),1977. 337 PreliminaryReportontheCaveSpider FaunaoftheRyukyuArchipelago By MatsueiSHIMOJANA FutenmaHighSchool,Iiutenma,GinowanCity,OkinawaPrefecture,Japan Synopsis SHIMOJANA,Matsuei(FutenmaHighSchool,Futenma,GinowanCity,OkinawaPre- fecture):PreliminaryreportonthecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyuArchipelago.Actor arachnol.,27(Specialnumber):337-365(1977). AsurveyofthecavespiderfaunaintheRyukyuArchipelagowascarriedoutfrom1966 to1976.Fourtytwospeciesofthirtysixgenerabelongingtotwentythreefamilieswererecord- edfrommanylimestonecavesintheRyukyuIslands.Therepresentativecavespidersinthe RyukyuArchipelagoare〃 σ∫ゴ7σ〃σ10〃8ψ 姥 ρガ∫,ノ7αZ6ガ勿)!o〃6!σo々 勿 σ"σ6η ∫ガ3,の60667σ1σ 〃76σ♂σ andTetrablemmashimojanaietc.Amongofthem,SpeoceralaureatesandTetrablemma shimojanaiarewidelydistributedintheRyukyuChain.ThecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyu ArchipelagoismuchdifferentfromtheJapaneseIslands. Introduction ThecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyuIslandshasbeenreportedbyDr・T・ YAGINuMA(1962,1970),Dr.T.KoMATsu(1968,1972,1974)andthepresentauthor (1973),butthenumberofrecordedspeciesisfewandfragmentary・ BiospeleologicalsurveyoftheRyukyuArchipelagohavebeencarriedoutbythe author,andhehascollectedmanykindsofsubterraneananimalsfrommanylimestone caves. Thepresentpaperdealswiththespiderfaunadisclosedduringthesesurveys. Befbregoingfurtherintothesubjects,theauthorwishestoexpresshishearty thankstoDr.TakeoYAGINuMAofOhtemonGakuinUniversity,Osaka,Dr.Shun-ichi UENoofNationalScienceMuseum,Tokyo,Dr.SadaoIKEHARAofUniversityofthe Ryukyus,Okinawa,Dr.ToshihiroKoMATsuofMatsumotoDentalCollege,Nagano -

Onna Village Illustration Map

Onna Village Illustration Map Onna Sunset Coast Road This is the name given to the North-South 27 km (Ukaji to Nakama) Onna Village stretch of Prefectural Road 6 and National Route 58, which passes through Onna Village along the sea. Out of numerous recommen- Area:50.82k㎡ dations of a nickname from the public, this name was chosen to Population:11,089人 reflect the beautiful sunset view. The area with this designation was (As of January 2021) extended in the spring of 2014. The sea area within Onna Village is designated the Okinawa Seashore National Park and at dusk, the clear sky and waters are wrapped in a magical orange hue. → ❶ Manzamo (Prefectural Designated Scenic Beauty) ❶ Manzamo Tourist Facility ❷ Onna Village Seaside Park Nabee Beach The park features a flat meadow that extends to the edge This facility has souvenir shops, restaurants, an You can enjoy BBQ and marine sports throughout To Nago of a 20 m-high Ryukyu limestone cliff. The name is said exhibition space and an observatory. It is a the year at the beach. Protective jellyfish nets are Halekulani Okinawa [ Language] to originate from the words of the former king of Ryukyu, three-story building with a local specialty corner installed from April until the end of October. The UMITO PLAGE Shokei, who praised the place as being “a Mo (field) that on the first floor, restaurants and shops on the beach is located inside a bay so the sea is relatively The Atta Okinawa is big enough for 10,000 people (Man) to sit (za).” The second floor, and an observatory overlooking the calm, and you can enjoy swimming safely.The Hyatt Regency sunset is also beautiful and shouldn’t be missed. -

Corporate Guide.Indd

Corporate Guide Corporate Guide Published/March 2016 Business Planning Division, Planning & Research Department, The Okinawa Development Finance Corporation 1-2-26 Omoromachi, Naha-shi, Okinawa 900-8520 TEL.098-941-1740 FAX.098-941-1925 http://www.okinawakouko.go.jp/ ◎This pamphlet has been prepared using environmentally-friendly vegetable oil ink and recycled paper. CORPORATE GUIDE CONTENTS Overview of The Okinawa Development Finance Corporation Additional Materials Profile 02 History 20 Overview of Operations 03 Organization 21 Branches 22 Outline of Loans and Investment Systems Types of Funds 06 Industrial Development Loans 07 Small and Medium-sized Enterprise(SME) Loans 08 Micro Business Loans 09 Environmental Health Business Loans 10 Fuzhou Medical Service Loans 11 Taipei Primary Sector Loans 12 (Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries) Housing Loans 13 Investments 14 Investments for the Creation of New Businesses 15 The Okinawa Development Finance Corporation Unique Funding Systems 16 Io-Torishima Island Okinawa Islands Iheya Island Izena Island Aguni Island Ie Island Okinawa Main Island Kume Island Senkaku Islands Taisho Island Kerama Islands Kuba Island Kitadaito Island Overview of The Okinawa Uotsuri Island Minamidaito Island Development Finance Corporation Daito Islands Irabu Island Miyako Island Sakishima Islands Profile ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 02 Yonaguni Island Tarama Island Miyako Islands Iriomote Island Ishigaki Island ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ Okidaito Island Overview of Operations -

US Military Facilities and Areas

1 2 Although 59 years have passed since the end of the Second World War, Okinawa, which accounts for only 0.6 percent of Japan's total land area, still hosts vast military bases, which represent approximately 74.7 percent of all facilities exclusively used by U.S. Forces Japan. U.S. military bases account for roughly 10.4 percent of the total land area of Okinawa, and 18.8 percent of the main island of Okinawa where population and industries are concentrated. Number of Facilities 3 Sapporo Japan Sea Sendai Seoul THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA Tokyo Osaka Yellow Sea Pusan Nagoya Fukuoka JAPAN Shanghai Kagoshima East China Sea Ryukyu OKINAWA Fuzhou Islands Naha Taipei Miyako Island Ishigaki Island 500Km TAIWAN 1,000Km Luzon THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES 1,500Km Manila 2,000Km Mindanao Palau Borneo Okinawa, which accounts for approximately 0.6% of the total land area of Japan, is the nation's southwestern-most prefecture. It consists of 160 islands, which are scattered over a wide area of ocean span- ning 1,000km from east to west and 400km from north to south. Approximately 1.35 million people live on fifty of these islands. From the prefectural capital of Naha city, it takes about two hours and 30 minutes to fly to Tokyo (approx. 1,550km), one hour and 30 minutes to Shanghai, China (approx. 820km), and one hour to Taipei, Tai- wan (approx. 630km). As Okinawa is situated in a critical location connecting mainland Japan, the Chinese 4 Continent and the nations of Southeast Asia, we expect that Okinawa will become a center for exchange be- tween Japan and the various nations of East and Southeast Asia. -

NAHA-Shi HAEBARU -Cho YONABARU -Cho NISHIHARA-Cho

IE-Son IE-JIMA KOURI-JIMA Buses for Naha stop Hotel Orion Motobu resort & spa Bise Fukugi Namiki-iriguchi Buses for Naha don’t stop Emerald beach-mae Centurion resort vintage Okinawa Churaumi Kinen Koen-mae (Churaumi aquarium) Hanasaki marche-mae NAKIJIN-Son Karry Condo Churaumi MIYAGI-JIMA YAGAJI-JIMA MINNA-JIMA SESOKO-JIMA MOTOBU-Cho HANEJI-NAIKAI Motobu port OU-JIMA Hotel Resonex Nago NAGO Bus Terminal Nago Shiyakusho mae NAGO-WAN Wansaka Oura Park Kanehide Kise Beach Palace KANUCHA Resort The Busena Terrace NAGO-Shi Okinawa Mariott Resort & Spa OURA-WAN Kariyushi beach-mae Halekulani Okinawa The Ritz Carlton Okinawa Okinawa Kariyushi Beach Resort Ocean Spa Halekulani Okinawa-mae Hyatt Regency Seragaki Island Okinawa ANA Intercontinental Manza Beach Resort Nabee beach-mae GINOZA-Son ONNA-Son KIN-Cho Rizzan Sea Park Hotel Tancha Bay Sheraton Okinawa Sun Marina Resort Sun marina beach-mae Kafuu Resort Fuchaku Hotel Monterey Okinawa Spa & Resort Condo Hotel Tiger beach-mae Hotel Moon Beach Hiyori ocean resort Okinawa Renaissance Resort Okinawa Okinawa Zampamisaki Royal Hotel On-na Best western On-na -no-Eki KIN-WAN Hoshinoya Okinawa Yomitan Bus Terminal Hotel Nikko Alivila YOMITAN-Son IKEI-JIMA MIYAGI-SHIMA URUMA-Shi KADENA-Cho URUMA-Shi HENZA-JIMA CHATAN-Cho OKINAWA-Shi La’gent Hotel Okinawa Chatan Hilton Okinawa Chatan Double tree by Hilton Okinawa Chatan Vessel Hotel Campana Okinawa American village-mae HAMAHIGA-JIMA The Beach Tower Okinawa KITANAKAGUSUKU-Son GINOWAN-Shi Laguna Garden Hotel Moon Ocean Ginowan Hotel & Residence NAKAGUSUKU-Son San-A Parco city NAKAGUSUKU-WAN URASOE-Shi Urasoe Tedako Maeda Uranishi Kyozuka TSUKEN-JIMA Furujima Shiritsu Byoin-mae Ishimine NISHIHARA-Cho Omoromachi Gibo Sta. -

OKINAWA, JAPAN August 16 - 26, 2018

OKINAWA, JAPAN August 16 - 26, 2018 NAHA • ITOMAN • NAKAGAMI • KUNIGAMI • YOMITAN THE GAIL PROJECT: AN OKINAWAN-AMERICAN DIALOGUE Dear UC Santa Cruz Alumni and Friends, I’m writing to invite you along on an adventure: 10 days in Okinawa, Japan with me, a cohort of Gail Project undergraduates and fellow travelers, all exploring the history, tradition, and culture of this unique and significant island. We will visit caves that were once forts in the heart of battle, winding markets with all of the tastes, smells, and colors you can imagine, shrines that will fill you with peace, and artisans who will immerse you into their craft. We will overlook military bases as we think about the American Occupation and the impacts of that relationship. We will eat Okinawan soba (noodles with pork), sample Goya (bitter melon), learn the intricate steps that create the dyed cloth known as Bingata, and dance to traditional Okinawan music. This is a remarkable opportunity for many reasons, as this trip is the first of its kind at UC Santa Cruz. I’m also proud to provide you with a journey unlike any you will have at other universities, as we are fusing the student and alumni experience. Our Gail Project students, while still working on their own undergraduate research, will make special appearances with the travelers and act as docents and guides at various sites along the way. This experience will allow travelers to meet and learn along with the students, and will offer insight into UC Santa Cruz’s commitment to hands-on research opportunities for undergraduates. -

Title Studies of the Third Miyakojima Typhoon -Its Characteristics and The

Studies of the Third Miyakojima Typhoon -Its Characteristics Title and the Damage to Structures- ISHIZAKI, Hatsuo; YAMAMOTO, Ryozaburo; MITSUTA, Author(s) Yasushi; MUROTA, Tatsuo; MAITANI, Toshihiko Bulletin of the Disaster Prevention Research Institute (1969), Citation 19(1): 45-85 Issue Date 1969-08 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/124765 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Bull. Disas. Prey. Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ., Vol. 19, Part 1, No. 153, Aug. 1969 45 Studies of the Third Miyakojima Typhoon -Its Characteristics and the Damage to Structures- By Hatsuo ISHIZAKI, Ryozaburo YAMAMOTO, Yasushi MITSUTA, Tatsuo MUROTA and Toshihiko MAITANI ( Manuscript recieved May 31, 1969) Abstract An expedition was made to Okinawa for the study of the Third Miyakojima Typhoon, which brought about serious damage there in September 1968. The meteorological characteristics and the damage to buildings were examined in comparison with those of the Second Miyakojima Typhoon, which struck the same region in 1966. The results are described in this paper following the checking rules which were advised to UNESCO by the AD HOC Working Group on Missions to Areas Damaged by Severe Wind Storms. 1. Introduction From 23rd to 24th September 1968, severe wind storms caused by the Third Miyakojima Typhoon (6816, Della) devastated many communities in Okinawa. The damage was severe and widespread over buildings, services, crops, trees, ships and telephone lines. The Miyakojima Islands suffered, more than any other islands, from the destructive force of the wind, where a maximum wind speed of 54.3 m/sec and a maximum peak gust of 79.8m/sec were observed and as many as 807 houses were completely destroyed. -

A Simple Ikat Sash from Southern Okinawa: Symbol of Island Identity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 A Simple Ikat Sash From Southern Okinawa: Symbol Of Island Identity Amanda Mayer Stinchecum Independent scholar based in New York Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Stinchecum, Amanda Mayer, "A Simple Ikat Sash From Southern Okinawa: Symbol Of Island Identity" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 548. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/548 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A SIMPLE IKAT SASH FROM SOUTHERN OKINAWA: SYMBOL OF ISLAND IDENTITY ©Amanda Mayer Stinchecum INTRODUCTION ( When I began this project in 1999,1 set out to explore a large theme: the relation between ikat textiles and ritual in Yaeyama, the southernmost island-group of Okinawa prefecture.1 I hoped to trace direct links to Southeast Asia, imagined by many Japanese and Okinawan scholars as the source of Ryukyuan ikat.. I set out to pursue the histories ( of two ikat textiles—a sash and a headscarf—used on Taketomi, linked, in legend, to ceremonial or ritual contexts, and intended to include ikat garments worn by women on ceremonial occasions. As my study unfolded, the persistence of the legend associated with the sash in spite of any evidence of ritual use manifestations of that legend today, ( and the complex history that underlies it drew me more and more to concentrate on that / one simple object.