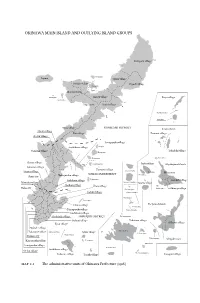

Map 12.1 the Administrative Units of Okinawa Prefecture (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Has Still Yet to Recognize Ryukyu/Okinawan Peoples

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan Prepared for 128th Session, Geneva, 2 March - 27 March, 2020 Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. II. Introduction The nation of Japan has made some significant strides in addressing historical issues of marginalization and discrimination against the Ainu Peoples. However, Japan has not made the same effort to address such issues regarding the Ryukyu Peoples. Both Peoples have been subject to historical injustices such as suppression of cultural practices and language, removal from land, and discrimination. Today, Ainu individuals continue to suffer greater rates of discrimination, poverty and lower rates of academic success compared to non-Ainu Japanese citizens. Furthermore, the dialogue between the government of Japan and the Ainu Peoples continues to be lacking. The Ryukyu Peoples continue to not be recognized as Indigenous by the Japanese government and face the nonconsensual use of their traditional lands by the United States military. -

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Procedure for Marrying Japanese in Okinawa

Procedure for Marrying Japanese in Okinawa Affidavit of Competency to Marry (Required Document for marriage in Japan): Legal will assist with completion and endorsement of Affidavit of Competency to Marry for the service member. Translations: Have Affidavit of Competency to Marry Translated into Japanese. Translate Birth Certificate into Japanese or use a Passport. Complete Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage) in Japanese. - This form can be obtained from any City Hall office in Japan. - Two witnesses, 20 years of age or older are required. If they are not Japanese, they must provide proof of citizenship in the form of a Birth Certificate with translation or Passport. City Hall Office: Must go to City Hall where fiancée’s address is registered or where Koseki (Family Tree) is filed Bring the following: Konin Todoke (Notification of Marriage) Original documents: Birth Certificate or Passports for the service member. Affidavit of Competency to Marry for the service member. Translated Affidavit of Competency to Marry. Translated Birth Certificate. Copies of witnesses citizenship documents and translations (if applicable). Another form of picture ID. Koseki Tohon. - City hall officials register marriage and issue Marriage Certificate. - Large certificate (A3) has witness names on it (associated costs). - Small certificate (B4) (associated costs). Translation Office: Translate marriage certificate into English (must be “official English translation”). Personnel Office (IPAC): Present Marriage Certificate with translation. Bring all the necessary documents to IPAC for your new spouse to acquire military I.D card. Please call IPAC ID section at 645-4038/5742 for more information. Version 2. Location: Building 5717 Camp Foster, down the hill from the Naval Hospital. -

Practical and Advanced Renewable Energy in Okinawa

The First International Workshop on Open Energy Systems (14-15 January 2014, OIST) Practical and Advanced Renewable Energy in Okinawa Dr. Jun-ichiro Giorgos TSUTSUMI Professor, Faculty of Engineering E-mail: [email protected] Contents of Presentation • Emission of Green House Gas from Energy • Ordinary Popular Natural Energy in Okinawa – Natural Energy (Photovoltaic System, Wind Turbine) – Recycle Energy (Waste Heat, Digested Gas, BDF) • Hawaii-Okinawa Clean Energy Partnership – Smart Grid System, OTEC, Energy Saving, People Exchange • Energy Research in University of the Ryukyus – Remote Control, Ocean Biomass, Solar Heater, Power Stabilizer • Smart Energy Projects by Okinawa Prefecture – Smart Energy Houses, Leveling System, Miyako Projects, etc. • Energy Projects in Miyako Island – Whole Island EMS, PV on Rented Roofs, Small EV • Remarks in Development of Renewable Energy Global Air Temperature and CO2 Concentration Industrial Revolu0on CO2 Emission Rate from Fossil Fuels Heating values and CO2 emission rates by combustion of various fossil fuels. CO2 emission: Coal > Oil > Gas. CO2 Emission Rate by Electric Power Companies before Fukushima “Adjusted rate” means the emission rates adjusted by the carbon credits of Kyoto mechanism. Mega Solar Fields in Okinawa (1) Fukuzato, Miyakojima (4,000kW) Okinawa Electric Power Co. (2) Abu, Nago (1,000kW) Okinawa Electric Co. (3) Ikehara, Okinawa (2,000kW) EcoLumiere LLC. Mega Solar Energy Field in Miyako Island Damages on wind turbines By typhoon 0314 (Maemi) New Type of Tiltable Wind -

KAKEHASHI Project Okinawa Program the 1 Slot Program Report

Japan’s Friendship Ties Program (USA) KAKEHASHI Project Okinawa Program the 1st slot Program Report 1. Program Overview Under the “KAKEHASHI Project” of Japan’s Friendship Ties Program, 42 high school students and 4 supervisors from the United States visited Japan from December 6th to December 13th, 2016 to participate in the program aimed at promoting their understanding of Japan with regard to Japanese politics, economy, society, culture, history, and foreign policy. Through lecture by ministry, observation of historical sites, school exchange, homestay, and other experiences, the participants enjoyed a wide range of opportunities to improve their understanding of Japan and shared their individual interests and experiences through SNS. Based on their findings and learning in Japan, each group of participants made a presentation in the final session and reported on the action plans to be taken after returning to their home country. 【Participating Countries and Number of Participants】 U.S.A. 46 Participants (A: Illinois University Laboratory High School, B: Fort Hayes Arts and Academic High School) 【Prefectures Visited】 Tokyo, Okinawa 2. Program Schedule December 6th (Tue) Arrival at Narita International Airport December 7th (Wed) [Orientation] [Lecture] North American Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Foreign Affairs “Japan’s Foreign Policy” [Historical Landmark] Imperial Palace Move to Okinawa December 8th (Thu) [Historical Facilities] Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, Peace Memorial Park [Historical Landmark] Shurijo Castle [Observation] Okinawa Prefectural Museum [Cultural Experience] Eisa dance 1 December 9th (Fri) [School Experience・Homestay] Okinawa Prefectural Naha Kokusai High School (Group A), Okinawa Prefectural Nago High School (Group B) December 10th (Sat) [Homestay] December 11th (Sun) [Homestay] Farewell Party [Workshop] December 12nd (Mon) Move to Tokyo [Reporting Session] December 13th (Tue) [Historical Landmark] Asakusa [Historical Landmark] Meiji Jingu Shrine Departure from Narita International Airport 3. -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

Higashi Village

We ask for your understanding Cape Hedo and cooperation for the environmental conservation funds. 58 Covered in spreading rich green subtropical forest, the northern part of 70 Okinawa's main island is called“Yanbaru.” Ferns and the broccoli-like 58 Itaji trees grow in abundance, and the moisture that wells up in between Kunigami Village Higashi Convenience Store (FamilyMart) Hentona Okinawa them forms clear streams that enrich the hilly land as they make their way Ie Island Ogimi Village towards the ocean. The rich forest is home to a number of animals that Kouri Island Prefecture cannot be found anywhere else on the planet, including natural monu- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium Higashi Nakijin Village ments and endemic species such as the endangered Okinawa Rail, the (Ocean Expo Park) Genka Shioya Bay Village 9 Takae Okinawan Woodpecker and the Yanbaru Long-Armed Scarab Beetle, Minna Island Yagaji Island 331 Motobu Town 58 Taira making it a cradle of precious flora and fauna. 70 Miyagi Senaga Island Kawata Village With its endless and diverse vegetation, Yanbaru was selected as a 14 Arume Gesashi proposed world natural heritage site in December 2013. Nago City Living alongside this nature, the people of Yanbaru formed little settle- 58 331 ments hugging the coastline. It is said that in days gone by, lumber cut Kyoda I.C. 329 from the forest was passed from settlement to settlement, and carried to Shurijo Castle. Living together with the natural blessings from agriculture Futami Iriguchi Cape Manza and fishing, people's prayers are carried forward to the future even today Ginoza I.C. -

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” Under the Japan-U.S

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” under the Japan-U.S. Alliance August 10-12, 2013 International Geographical Union (IGU) 2013 Kyoto Regional Conference Commission on Political Geography Post-Conference Field Trip In Collaboration with Political Geography Research Group, Human Geographical Society of Japan and Okinawa Geographical Society Contents Organizers and Participants………………………………………………………………………….. p. 2 Co-organizers Assistants Supporting Organizations Informants Participants Time Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 4 Route Maps……………………………………………………………………………………….…..p. 5 Naha Airport……………………………………………………………………………………….... p. 6 Domestic Flight Arrival Procedures Domestic Flight Departure Procedures Departing From Okinawa during a Typhoon Traveling to Okinawa during a Typhoon Accommodation………………………………………...…………………………………………..... p. 9 Deigo Hotel History of Deigo Hotel History of Okinawa (Ryukyu)………………………………………..………………………............. p. 11 From Ryukyu to Okinawa The Battle of Okinawa Postwar Occupation and Administration by the United States Post-Reversion U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa…………………………………………………………………...… p. 14 Futenma Air Station Kadena Air Base Camp Schwab Camp Hansen Military Base Towns in Okinawa………………………………………………………...………….. p. 20 Political Economic Profile of Selected Base Towns Okinawa City (formerly Koza City) Chatan Town Yomitan Village Henoko, Nago City Kin Town What to do in Naha……………………………………………………………………………...… p. 31 1 Organizers -

The Enduring Myth of an Okinawan Struggle: the History and Trajectory of a Diverse Community of Protest

The Enduring Myth of an Okinawan Struggle: The History and Trajectory of a Diverse Community of Protest A dissertation presented to the Division of Arts, Murdoch University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2003 Miyume Tanji BA (Sophia University) MA (Australian National University) I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research. It contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any university. ——————————————————————————————— ii ABSTRACT The islands of Okinawa have a long history of people’s protest. Much of this has been a manifestation in one way or another of Okinawa’s enforced assimilation into Japan and their differential treatment thereafter. However, it is only in the contemporary period that we find interpretations among academic and popular writers of a collective political movement opposing marginalisation of, and discrimination against, Okinawans. This is most powerfully expressed in the idea of the three ‘waves’ of a post-war ‘Okinawan struggle’ against the US military bases. Yet, since Okinawa’s annexation to Japan in 1879, differences have constantly existed among protest groups over the reasons for and the means by which to protest, and these have only intensified after the reversion to Japanese administration in 1972. This dissertation examines the trajectory of Okinawan protest actors, focusing on the development and nature of internal differences, the origin and survival of the idea of a united ‘Okinawan struggle’, and the implications of these factors for political reform agendas in Okinawa. It explains the internal differences in organisation, strategies and collective identities among the groups in terms of three major priorities in their protest. -

Page 1 ACTA ARACHNOL., 27, Special Number), 1977. 337

ACTAARACHNOL.,27,Specialnumber),1977. 337 PreliminaryReportontheCaveSpider FaunaoftheRyukyuArchipelago By MatsueiSHIMOJANA FutenmaHighSchool,Iiutenma,GinowanCity,OkinawaPrefecture,Japan Synopsis SHIMOJANA,Matsuei(FutenmaHighSchool,Futenma,GinowanCity,OkinawaPre- fecture):PreliminaryreportonthecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyuArchipelago.Actor arachnol.,27(Specialnumber):337-365(1977). AsurveyofthecavespiderfaunaintheRyukyuArchipelagowascarriedoutfrom1966 to1976.Fourtytwospeciesofthirtysixgenerabelongingtotwentythreefamilieswererecord- edfrommanylimestonecavesintheRyukyuIslands.Therepresentativecavespidersinthe RyukyuArchipelagoare〃 σ∫ゴ7σ〃σ10〃8ψ 姥 ρガ∫,ノ7αZ6ガ勿)!o〃6!σo々 勿 σ"σ6η ∫ガ3,の60667σ1σ 〃76σ♂σ andTetrablemmashimojanaietc.Amongofthem,SpeoceralaureatesandTetrablemma shimojanaiarewidelydistributedintheRyukyuChain.ThecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyu ArchipelagoismuchdifferentfromtheJapaneseIslands. Introduction ThecavespiderfaunaoftheRyukyuIslandshasbeenreportedbyDr・T・ YAGINuMA(1962,1970),Dr.T.KoMATsu(1968,1972,1974)andthepresentauthor (1973),butthenumberofrecordedspeciesisfewandfragmentary・ BiospeleologicalsurveyoftheRyukyuArchipelagohavebeencarriedoutbythe author,andhehascollectedmanykindsofsubterraneananimalsfrommanylimestone caves. Thepresentpaperdealswiththespiderfaunadisclosedduringthesesurveys. Befbregoingfurtherintothesubjects,theauthorwishestoexpresshishearty thankstoDr.TakeoYAGINuMAofOhtemonGakuinUniversity,Osaka,Dr.Shun-ichi UENoofNationalScienceMuseum,Tokyo,Dr.SadaoIKEHARAofUniversityofthe Ryukyus,Okinawa,Dr.ToshihiroKoMATsuofMatsumotoDentalCollege,Nagano -

Onna Village Illustration Map

Onna Village Illustration Map Onna Sunset Coast Road This is the name given to the North-South 27 km (Ukaji to Nakama) Onna Village stretch of Prefectural Road 6 and National Route 58, which passes through Onna Village along the sea. Out of numerous recommen- Area:50.82k㎡ dations of a nickname from the public, this name was chosen to Population:11,089人 reflect the beautiful sunset view. The area with this designation was (As of January 2021) extended in the spring of 2014. The sea area within Onna Village is designated the Okinawa Seashore National Park and at dusk, the clear sky and waters are wrapped in a magical orange hue. → ❶ Manzamo (Prefectural Designated Scenic Beauty) ❶ Manzamo Tourist Facility ❷ Onna Village Seaside Park Nabee Beach The park features a flat meadow that extends to the edge This facility has souvenir shops, restaurants, an You can enjoy BBQ and marine sports throughout To Nago of a 20 m-high Ryukyu limestone cliff. The name is said exhibition space and an observatory. It is a the year at the beach. Protective jellyfish nets are Halekulani Okinawa [ Language] to originate from the words of the former king of Ryukyu, three-story building with a local specialty corner installed from April until the end of October. The UMITO PLAGE Shokei, who praised the place as being “a Mo (field) that on the first floor, restaurants and shops on the beach is located inside a bay so the sea is relatively The Atta Okinawa is big enough for 10,000 people (Man) to sit (za).” The second floor, and an observatory overlooking the calm, and you can enjoy swimming safely.The Hyatt Regency sunset is also beautiful and shouldn’t be missed.