Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada

Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada To cite this version: Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada. Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni). Kiefer, Ferenc; Blevins, James P.; Bartos, Huba. Perspectives on morphological organization: Data and analyses, Brill, pp.31-49, 2017, 9789004342910. 10.1163/9789004342934_004. hal-01493096 HAL Id: hal-01493096 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01493096 Submitted on 20 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Kiefer, Ferenc & Blevins, James P. & Bartos, Huba (eds,), Perspectives on morphological organization: Data and analyses, 31–49. Leiden: Brill. isbn: 9789004342910. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004342934. chapter 2 Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard and Masahiro Yamada 1 Dunan and the other Japonic languages 1.1 Japanese and the other Japonic languages Most Japonic languages have a relatively simple and transparent morphology.1 Their verb morphology is usually characterized by a highly agglutinative struc- ture that exhibits little morphophonology, with only a few conjugation classes and a handful of irregular verbs. For instance, Modern Standard Japanese has only two regular conjugation classes: a consonant-stem class (C) and a vowel- stem class (V). -

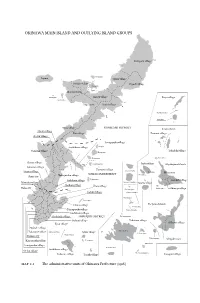

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Effects of Constructing a New Airport on Ishigaki Island

Island Sustainability II 181 Effects of constructing a new airport on Ishigaki Island Y. Maeno1, H. Gotoh1, M. Takezawa1 & T. Satoh2 1Nihon University, Japan 2Nihon Harbor Consultants Ltd., Japan Abstract Okinawa Prefecture marked the 40th anniversary of its reversion to Japanese sovereignty from US control in 2012. Such isolated islands are almost under the environment separated by the mainland and the sea, so that they have the economic differences from the mainland and some policies for being active isolated islands are taken. It is necessary to promote economical measures in order to increase the prosperity of isolated islands through initiatives involving tourism, fisheries, manufacturing, etc. In this study, Ishigaki Island was considered as an example of such an isolated island. Ishigaki Island is located to the west of the main islands of Okinawa and the second-largest island of the Yaeyama Island group. Ishigaki Island falls under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, which is situated approximately half-way between Kyushu and Taiwan. Both islands belong to the Ryukyu Archipelago, which consists of more than 100 islands extending over an area of 1,000 km from Kyushu (the southwesternmost of Japan’s four main islands) to Taiwan in the south. Located between China and mainland Japan, Ishigaki Island has been culturally influenced by both countries. Much of the island and the surrounding ocean are protected as part of Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park. Ishigaki Airport, built in 1943, is the largest airport in the Yaeyama Island group. The runway and air security facilities were improved in accordance with passenger demand for larger aircraft, and the airport became a tentative jet airport in May 1979. -

Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor

Samsuddin M. F., Hamzah A. H., & Mohd Radzi F. dealogy Journal, 2020 Vol. 5, No. 2, 79-88 Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor Muhammad Fitri Samsuddin1, Azni Hanim Hamzah2, Fazlina Mohd Radzi3, Siti Nurul Akma Ahmad4, Mohd Faizul Noorizan6, Mohd Ali Azraie Bebit6 12356Faculty of Art & Design, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka 4Faculty of Business & Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka Authors’ email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Published: 28 September 2020 ABSTRACT Malaysian textile motifs especially the Batik motifs and its product are highly potential to sustain in a global market. The integration of intercultural design of Malaysian textile motifs and Japanese textile motifs will further facilitate both textile industries to be sustained and demanded globally. Besides, Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs can be creatively design on other platforms not limited to the clothes. Therefore, this study is carried out with the aim of integrating the Malaysian textile motifs specifically focuses on batik motifs and Japanese textile motifs through product diversification. This study focuses on integrating both textile motifs and diversified the design on a home décor including wall frame, table clothes, table runner, bed sheets, lamp shades and other potential home accessories. In this concept paper, literature search was conducted to describe about the characteristics of both Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs and also to reveal insights about the practicality and the potential of combining these two worldwide known textile industries. The investigation was conducted to explore new pattern of the combined textiles motifs. -

Nansei Islands Biological Diversity Evaluation Project Report 1 Chapter 1

Introduction WWF Japan’s involvement with the Nansei Islands can be traced back to a request in 1982 by Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh. The “World Conservation Strategy”, which was drafted at the time through a collaborative effort by the WWF’s network, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), posed the notion that the problems affecting environments were problems that had global implications. Furthermore, the findings presented offered information on precious environments extant throughout the globe and where they were distributed, thereby providing an impetus for people to think about issues relevant to humankind’s harmonious existence with the rest of nature. One of the precious natural environments for Japan given in the “World Conservation Strategy” was the Nansei Islands. The Duke of Edinburgh, who was the President of the WWF at the time (now President Emeritus), naturally sought to promote acts of conservation by those who could see them through most effectively, i.e. pertinent conservation parties in the area, a mandate which naturally fell on the shoulders of WWF Japan with regard to nature conservation activities concerning the Nansei Islands. This marked the beginning of the Nansei Islands initiative of WWF Japan, and ever since, WWF Japan has not only consistently performed globally-relevant environmental studies of particular areas within the Nansei Islands during the 1980’s and 1990’s, but has put pressure on the national and local governments to use the findings of those studies in public policy. Unfortunately, like many other places throughout the world, the deterioration of the natural environments in the Nansei Islands has yet to stop. -

T.C. Istanbul Aydin Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

T.C. İSTANBUL AYDIN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TEKSTİLDE SHIBORI VE STENCIL BASKI TEKNİĞİNİN SANATSAL UYGULAMALARI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Emine YILDIZ (Y1312.240003) Görsel Sanatlar Ana Sanat Dalı Görsel Sanatlar Programı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Bayram YÜKSEL Ocak, 2017 YEMİN METNİ Yüksek lisans tezi olarak sunduğum” Tekstilde Shibori Ve Stencil Baskı Tekniğinin Sanatsal Uygulamaları” adlı çalışmanın, tezin proje safhasından sonuçlanmasına kadarki bütün süreçlerde bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düşecek bir yardıma başvurulmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin Bibliyoğrafya’da gösterilenlerden oluştuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmış olduğunu belirtir ve onurumla beyan ederim.( 05.01.2017) Emine YILDIZ iii ÖNSÖZ İnsanoğlunun örtünme ve doğa koşullarından korunma gereksinimi ilk insandan bu yana varolagelmiştir. Zaman içerisinde, sosyal, ekonomik ve kültürel değişimin yaşanması giyiminde farklı yönlere kaymasını engelleyememiştir. Giderek globalleşen dünyamız da, tekstil ürünlerinin desen, kumaş, renk çeşitliliğine rağmen, düşünsel gelişimin, sanatsal yaklaşımına yetemediği anlaşılmıştır. Günümüz insanları teknolojinin ilerlemesi ve aynı tarz giyimden bıkmış ve farklı tasarım ve farklı kumaş desenli kıyafet isteğine yönelmiştir. Japon sanatı shibori çok eski geleneği bu gün yeryüzüne tekrar çıkarmıştır. İnsanlarımızın bu isteğine cevap veren ve hatta duygularını kumaşıyla bütünleştiren bu sanat, bir çok teknikte değişik etkileşimler ve değişik formlar meydana getirmiştir. Shibori tekstil ürünlerini hiçe -

Higashi Village

We ask for your understanding Cape Hedo and cooperation for the environmental conservation funds. 58 Covered in spreading rich green subtropical forest, the northern part of 70 Okinawa's main island is called“Yanbaru.” Ferns and the broccoli-like 58 Itaji trees grow in abundance, and the moisture that wells up in between Kunigami Village Higashi Convenience Store (FamilyMart) Hentona Okinawa them forms clear streams that enrich the hilly land as they make their way Ie Island Ogimi Village towards the ocean. The rich forest is home to a number of animals that Kouri Island Prefecture cannot be found anywhere else on the planet, including natural monu- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium Higashi Nakijin Village ments and endemic species such as the endangered Okinawa Rail, the (Ocean Expo Park) Genka Shioya Bay Village 9 Takae Okinawan Woodpecker and the Yanbaru Long-Armed Scarab Beetle, Minna Island Yagaji Island 331 Motobu Town 58 Taira making it a cradle of precious flora and fauna. 70 Miyagi Senaga Island Kawata Village With its endless and diverse vegetation, Yanbaru was selected as a 14 Arume Gesashi proposed world natural heritage site in December 2013. Nago City Living alongside this nature, the people of Yanbaru formed little settle- 58 331 ments hugging the coastline. It is said that in days gone by, lumber cut Kyoda I.C. 329 from the forest was passed from settlement to settlement, and carried to Shurijo Castle. Living together with the natural blessings from agriculture Futami Iriguchi Cape Manza and fishing, people's prayers are carried forward to the future even today Ginoza I.C. -

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” Under the Japan-U.S

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” under the Japan-U.S. Alliance August 10-12, 2013 International Geographical Union (IGU) 2013 Kyoto Regional Conference Commission on Political Geography Post-Conference Field Trip In Collaboration with Political Geography Research Group, Human Geographical Society of Japan and Okinawa Geographical Society Contents Organizers and Participants………………………………………………………………………….. p. 2 Co-organizers Assistants Supporting Organizations Informants Participants Time Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 4 Route Maps……………………………………………………………………………………….…..p. 5 Naha Airport……………………………………………………………………………………….... p. 6 Domestic Flight Arrival Procedures Domestic Flight Departure Procedures Departing From Okinawa during a Typhoon Traveling to Okinawa during a Typhoon Accommodation………………………………………...…………………………………………..... p. 9 Deigo Hotel History of Deigo Hotel History of Okinawa (Ryukyu)………………………………………..………………………............. p. 11 From Ryukyu to Okinawa The Battle of Okinawa Postwar Occupation and Administration by the United States Post-Reversion U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa…………………………………………………………………...… p. 14 Futenma Air Station Kadena Air Base Camp Schwab Camp Hansen Military Base Towns in Okinawa………………………………………………………...………….. p. 20 Political Economic Profile of Selected Base Towns Okinawa City (formerly Koza City) Chatan Town Yomitan Village Henoko, Nago City Kin Town What to do in Naha……………………………………………………………………………...… p. 31 1 Organizers -

Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art

School of Media Creative Arts and Social Inquiry (MCASI) Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art Kelsey Ashe Giambazi This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University July 2018 0 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Date: 15th July 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely express my thanks and gratitude to the following people: Dr. Ann Schilo for her patient guidance and supervisory assistance with my exegesis for the six-year duration of my candidacy. To learn the craft of writing with Ann has been a privilege and a joy. Dr. Anne Farren for her supervisory support and encouragement. To the staff of the Curtin Fashion Department, in particular Joanna Quake and Kristie Rowe for the daily support and understanding of the juggle of motherhood, work and ‘PhD land’. To Dr. Dean Chan for his impeccably thorough copy-editing and ‘tidying up’ of my bibliographical references. The staff in the School of Design and Art, in particular Dr. Nicole Slatter, Dr. Bruce Slatter and Dr. Susanna Castleden for being role models for a life with a balance of academia, art and family. My fellow PhD candidates who have shared the struggle and the reward of completing a thesis, in particular Fran Rhodes, Rebecca Dagnall and Alana McVeigh. -

The Enduring Myth of an Okinawan Struggle: the History and Trajectory of a Diverse Community of Protest

The Enduring Myth of an Okinawan Struggle: The History and Trajectory of a Diverse Community of Protest A dissertation presented to the Division of Arts, Murdoch University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2003 Miyume Tanji BA (Sophia University) MA (Australian National University) I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research. It contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any university. ——————————————————————————————— ii ABSTRACT The islands of Okinawa have a long history of people’s protest. Much of this has been a manifestation in one way or another of Okinawa’s enforced assimilation into Japan and their differential treatment thereafter. However, it is only in the contemporary period that we find interpretations among academic and popular writers of a collective political movement opposing marginalisation of, and discrimination against, Okinawans. This is most powerfully expressed in the idea of the three ‘waves’ of a post-war ‘Okinawan struggle’ against the US military bases. Yet, since Okinawa’s annexation to Japan in 1879, differences have constantly existed among protest groups over the reasons for and the means by which to protest, and these have only intensified after the reversion to Japanese administration in 1972. This dissertation examines the trajectory of Okinawan protest actors, focusing on the development and nature of internal differences, the origin and survival of the idea of a united ‘Okinawan struggle’, and the implications of these factors for political reform agendas in Okinawa. It explains the internal differences in organisation, strategies and collective identities among the groups in terms of three major priorities in their protest. -

Loom Abbreviation S JF January/February RH

Handwoven Index, 2012 – January/February 2018 Both authors and subjects are contained in the index. Keep in mind that people’s names can be either authors or subjects in an article. The column “Roving Reporters” is not indexed, nor is the “Letters” or “From the Editor,” unless it is substantial. Projects are followed by bracketed [ ] abbreviations indicating the shaft number and loom type if other than a regular floor loom. To find an article, use the abbreviations list below to determine issue and loom type. For instance, “Warped and twisted scarves. Handwoven: MJ12, 66-68 [4]” is a 4-shaft project found on pages 66-68 of the May/June 2012 issue. Issue Loom abbreviat abbreviation ions: s JF January/February RH Rigid heddle MA March/April F Frame loom MJ May/June P Peg or pin loom SO September/October C Card/tablet weave ND November/December I Inkle loom T Tapestry loom D Dobby loom 3-D weaving Weaving in 3-D. Handwoven: ND14, 63-64 A Abbarno, Luciano A weaver on the verge. Handwoven: ND12, 11 Abernathy-Paine, Ramona An Elizabethan sonnet in a shawl. Handwoven: JF14, 54-56 [10] Warped and twisted scarves. Handwoven: MJ12, 66-68 [4] absorbency Reflections on absorbency. Handwoven: SO14, 70-71 Acadian textiles Boutonné snowflake pillow. Handwoven: SO15, 67-68 [2, RH] Boutonné: an Arcadian legacy. Handwoven: SO15, 66-67 Cajun cotton. Handwoven: JF15, 66-67 Cajun-inspired cotton dish towels. Handwoven: JF15, 67-68 [4] Adams, Mark Tapestry through the ages. Handwoven: MJ15, 6 Adams, Theresa Blooming leaf runner. Handwoven: MA12, 36-37 [4] Adamson, Linda Summer and winter with a twist polka-dot towels. -

Coral Reefs of Japan

Yaeyama Archipelago 6-1-7 (Map 6-1-7) Province: Okinawa Prefecture Location: ca. 430 km southwest off Okinawa Island, including Ishigaki, Iriomote, 6-1-7-③ Kohama, Taketomi, Yonaguni and Hateruma Island, and Kuroshima (Is.). Features: Sekisei Lagoon, the only barrier reef in Japan lies between the southwestern coast of Ishigaki Island and the southeastern coast of Taketomi Island Air temperature: 24.0˚C (annual average, at Ishigaki Is.) Seawater temperature: 25.2˚C (annual average, at east off Ishigaki Is.) Precipitation: 2,061.1 mm (annual average, at Ishigaki Is.) Total area of coral communities: 19,231.5 ha Total length of reef edge: 268.4 km Protected areas: Iriomote Yonaguni Is. National Park: at 37 % of the Iriomote Is. and part of Sekisei Lagoon; Marine park zones: 4 zones in Sekisei 平久保 Lagoon; Nature Conservation Areas: Sakiyama Bay (whole area is designated as marine special zones as well); Hirakubo Protected Water Surface: Kabira and Nagura Bay in Ishigaki Is. 宇良部岳 Urabutake (Mt.) 野底崎 Nosokozaki 0 2km 伊原間 Ibarama 川平湾 Kabira Bay 6-1-7-① 崎枝湾 浦底湾 Sakieda Bay Urasoko Bay Hatoma Is. 屋良部半島 川平湾保護水面 Yarabu Peninsula Kabirawan Protected Water Surface ▲於茂登岳 Omototake (Mt.) 嘉弥真島 Koyama Is. アヤカ崎 名蔵湾保護水面 Akayazaki Nagurawan Protected Ishigaki Is. Water Surface 名蔵湾 Nagura Bay 竹富島タキドングチ 轟川 浦内川 Taketomijima Takedonguchi MP Todoroki River Urauchi River 宮良川 崎山湾自然環境保護地域 細崎 Miyara River Sakiyamawan 古見岳 Hosozaki 白保 Nature Conservation Area Komitake (Mt.) Shiraho Iriomote Is. 登野城 由布島 Kohama Is. Tonoshiro Yufujima (Is.) 宮良湾 Taketomi Is. Miyara Bay ユイサーグチ Yuisaguchi 仲間川 崎山湾 Nakama River 竹富島シモビシ Sakiyama Bay Taketomi-jima Shimobishi MP ウマノハピー 新城島マイビシ海中公園 Aragusukujima Maibishi MP Umanohapi Reef 6-1-7-② Kuroshima (Is.) 黒島キャングチ海中公園 上地島 Kuroshima Kyanguchi MP Uechi Is.