Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Uni Musos Struttin' at Australian Fashion Week USU

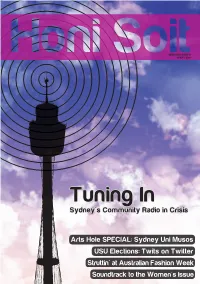

SEMESTER 1 WEEK 10 12 MAY, 2010 Tuning In Sydney's Community Radio in Crisis Arts Hole SPECIAL: Sydney Uni Musos USU Elections: Twits on Twitter Struttin' at Australian Fashion Week Soundtrack to the Women's Issue 2 This Week's: Smoke-free days: five. Swedish snack most likely to tear the editingCONTENTS team apart: Salt Sill Original With more quokkas Worst/bestthan question asked by an editor this week: “Sibella, will your recreational libraries HONI SOIT, EDITION 9 cater to the boom in 3D movies?” - Joe Smith-Davies, Manning Soapbox 12 MAY 2010 ever before. Most divisive pun: “Rob Chiarella learns that good art cums on small packages.” Thing that’s not as awesome as it sounds: turning off a computer with a hammer. The Post 03 The Arts-Hole 10 Letter rip, potato chip. SPECIAL EDITION: Jess Stirling, Jacinta Mulders, Bridie Connellan and Joe Payten catch up with our uni’s finest The Uni-Cycle 04 musical exports to talk sounds, Sydney and Zahra Anver thinks the answer is fairly obvious. the spotlight. Rob Chiarella learns that good art comes on small packages. The Mains 12 AA makes Oli Burton go AAAAAH! Daniel Zwi pricks his ears to a crisis in Tom Clement goes AAAAAH regarding AA. community radio. Carmen Culina thinks something’s fishery. To market, to market, for Chelsea Tabart. 05 The Lodgers 14 Ted Talas keeps it fResh. David Mack and Naomi Hart deliver 06 Women’s Honi was music to Joe Payten’s Honi’s final election rumours (and have the ears. decency to publish their names). -

Fashion's Influence on Garment Mass Production

Fashion’s Influence on Garment Mass Production: Knowledge, Commodities and the Capture of Value Sally Weller A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Strategic Economic Studies Victoria University, Melbourne AUSTRALIA October 2003 ABSTRACT In affluent communities, it is difficult to think about clothing without considering issues of fashion. Yet, in analyses of the garment industries, fashion is rarely considered in detail, and is certainly not analysed as a structuring force over the configuration of garment production industries. Yet through fashion, garments as commodities are complexly embedded in social and cultural processes and in the specificities of place. Although the structures of the global garment production industries have been the subject of numerous studies from a variety of theoretical perspectives, none hitherto have addressed the influence of fashion on the structures and locations of garment production. This thesis begins with the idea that fashion is a complex and influential form of knowledge. It explores the effects of fashion ideas on the global garment system through a case study of the ideas and commodity flows that bring fashions and garments to the Australian market. It traces the interconnections between global knowledge flows and global commodity flows in a manner attuned to the relationships between knowledge, power, industrial organisation and the capture of surplus value from the production system. The analysis highlights how Australia’s position in garment production is framed by its geographical position on the periphery of the fashion world. Fashion knowledge is a complex form of knowledge with four interrelated expressions. -

Adidas' Bjorn Wiersma Talks Action Sports Selling

#82 JUNE / JULY 2016 €5 ADIDAS’ BJORN WIERSMA TALKS ACTION SPORTS SELLING TECHNICAL SKATE PRODUCTS EUROPEAN MARKET INTEL BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MUCH MORE TREND REPORTS: BOARDSHORTS, CAMPING & OUTDOOR, SWIMWEAR, STREETWEAR, SKATE HARDWARE & PROTECTION 1 US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson HELLO #82 [email protected] At the time of writing, Europe is finally protection and our Skateboard Editor, Dirk seeing some much needed signs of summer. Vogel looks at how the new technology skate Surf & French Editor Iker Aguirre April and May, on the whole, were wet brands are introducing into their decks, wheels [email protected] across the continent, spelling unseasonably and trucks gives retailers great sales arguments green countryside and poor spring sales for for selling high end products. We also have Senior Snowboard Contributor boardsports retail. However, now the sun our regular features; Corky from Stockholm’s shines bright and rumours are rife of El Niño’s Coyote Grind Lounge claims this issue’s Tom Wilson-North tail end heating both our oceans and air right Retailer Profile after their second place finish [email protected] the way through the summer. All is forgiven. at last year’s Vans Shop Riot series. Titus from Germany won the competition in 2015 and their Skate Editor Dirk Vogel Our business is entirely dependent on head of buying, PV Schulz gives us an insight [email protected] Mother Nature and with the Wanderlust trend into his buying tricks and tips. that’s sparked a heightened lust for travel in Millenials, spurred on by their need to document Our summer tradeshow edition is thoughtfully German Editor Anna Langer just how “at one” with nature they are, SOURCE put together to provide retailers with an [email protected] explores a new trend category in our Camping & extensive overview of SS17’s trends to assist Outdoor trend report. -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor

Samsuddin M. F., Hamzah A. H., & Mohd Radzi F. dealogy Journal, 2020 Vol. 5, No. 2, 79-88 Integrating Malaysian and Japanese Textile Motifs Through Product Diversification: Home Décor Muhammad Fitri Samsuddin1, Azni Hanim Hamzah2, Fazlina Mohd Radzi3, Siti Nurul Akma Ahmad4, Mohd Faizul Noorizan6, Mohd Ali Azraie Bebit6 12356Faculty of Art & Design, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka 4Faculty of Business & Management, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Melaka Authors’ email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Published: 28 September 2020 ABSTRACT Malaysian textile motifs especially the Batik motifs and its product are highly potential to sustain in a global market. The integration of intercultural design of Malaysian textile motifs and Japanese textile motifs will further facilitate both textile industries to be sustained and demanded globally. Besides, Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs can be creatively design on other platforms not limited to the clothes. Therefore, this study is carried out with the aim of integrating the Malaysian textile motifs specifically focuses on batik motifs and Japanese textile motifs through product diversification. This study focuses on integrating both textile motifs and diversified the design on a home décor including wall frame, table clothes, table runner, bed sheets, lamp shades and other potential home accessories. In this concept paper, literature search was conducted to describe about the characteristics of both Malaysian and Japanese textile motifs and also to reveal insights about the practicality and the potential of combining these two worldwide known textile industries. The investigation was conducted to explore new pattern of the combined textiles motifs. -

T.C. Istanbul Aydin Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

T.C. İSTANBUL AYDIN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TEKSTİLDE SHIBORI VE STENCIL BASKI TEKNİĞİNİN SANATSAL UYGULAMALARI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Emine YILDIZ (Y1312.240003) Görsel Sanatlar Ana Sanat Dalı Görsel Sanatlar Programı Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Bayram YÜKSEL Ocak, 2017 YEMİN METNİ Yüksek lisans tezi olarak sunduğum” Tekstilde Shibori Ve Stencil Baskı Tekniğinin Sanatsal Uygulamaları” adlı çalışmanın, tezin proje safhasından sonuçlanmasına kadarki bütün süreçlerde bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düşecek bir yardıma başvurulmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin Bibliyoğrafya’da gösterilenlerden oluştuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmış olduğunu belirtir ve onurumla beyan ederim.( 05.01.2017) Emine YILDIZ iii ÖNSÖZ İnsanoğlunun örtünme ve doğa koşullarından korunma gereksinimi ilk insandan bu yana varolagelmiştir. Zaman içerisinde, sosyal, ekonomik ve kültürel değişimin yaşanması giyiminde farklı yönlere kaymasını engelleyememiştir. Giderek globalleşen dünyamız da, tekstil ürünlerinin desen, kumaş, renk çeşitliliğine rağmen, düşünsel gelişimin, sanatsal yaklaşımına yetemediği anlaşılmıştır. Günümüz insanları teknolojinin ilerlemesi ve aynı tarz giyimden bıkmış ve farklı tasarım ve farklı kumaş desenli kıyafet isteğine yönelmiştir. Japon sanatı shibori çok eski geleneği bu gün yeryüzüne tekrar çıkarmıştır. İnsanlarımızın bu isteğine cevap veren ve hatta duygularını kumaşıyla bütünleştiren bu sanat, bir çok teknikte değişik etkileşimler ve değişik formlar meydana getirmiştir. Shibori tekstil ürünlerini hiçe -

Nasty Gal Offices to Remain Open in Los Angeles

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 73, NUMBER 10 MARCH 3–9, 2017 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 72 YEARS BCBGMaxAzria Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Protection By Deborah Belgum Senior Editor BCBGMaxAzriaGroup, the decades-old Los Angeles apparel company that was one of the first on the contempo- rary fashion scene, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protec- tion in papers submitted Feb. 28 to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. The company’s Canadian affiliate is beginning a sepa- rate filing for voluntary reorganization proceedings under Canada’s Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act. Steps are being taken to close its freestanding stores in Canada and consoli- date its operations in Europe and Japan. The apparel venture, founded in 1989 by Max Azria, has been navigating through some tough financial waters in the past few years. New executives have been unable to turn the company around fast enough and now hope to finish the bankruptcy process in six months. ➥ BCBG page 9 Mitchell & Ness’ booth at the Agenda trade show in Las Vegas TRADE SHOW REPORT Sports Apparel Maker Mitchell & Ness Moving to Irvine Crowded Trade Show By Andrew Asch Retail Editor Schedule Cuts Into LA The North American licensed sportswear business is esti- tive officer. mated to be a multi-billion-dollar market, and Philadelphia- “This facility will house all of our product under one roof Textile Traffic headquartered brand Mitchell & Ness is making a gambit for and modernize our operations with the goal of providing a bigger chunk of it. It is scheduled to open its first West Coast gold-standard customer service. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

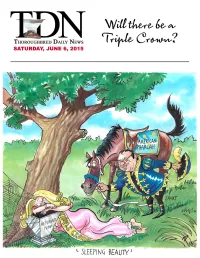

PEDIGREE INSIGHTS... Adding to Her Optional Claiming Score at Gulfstream Get Pedigree Expert Andrew Caulfield=S Mar

SATURDAY, JUNE 6, 2015 732-747-8060 $ TDN Home Page Click Here PHAROAH FIT, READY TO WEAR THE CROWN AROUND THE HORN From the time Sir Barton became the first to sweep Today=s G1 Investec Derby seems to hinge on one the GI Kentucky Derby, GI Preakness S. and GI Belmont question, and only Golden Horn (GB) (Cape Cross {Ire}) S. in 1919 until Citation became the eighth to run the can supply the answer as he enters the final quarter- table in 1948, the most time mile of Tesio=s famed ultimate test of the that transpired between Thoroughbred. There is no doubt that Anthony successful Triple Crown bids Oppenheimer=s homebred has a distinct class edge over was the 11 years between Sir all of his rivals based on his emphatic success in the Barton and Gallant Fox in premier trial, York=s G2 Dante S. May 14, which was 1930. With his 31-length termed a Amini Derby@ at the time. Form, mentality and demolition of the field in 1973, physicality aside, Secretariat snapped a 25-year however, the bay enters drought, while Seattle Slew this race without all and Affirmed made it three boxes ticked, as he is Triple Crowns in the space of unproven at this trip and six years in 1977 and 1978, his pedigree does not respectively. Since then, 13 shout a mile and a half have tried and 13 have been Baffert and Zayat out loud. Under the denied, but Zayat Stables= second dam is a mix of at Belmont Thursday American Pharoah (Pioneerof NYRA/Coglianese stamina and speed, with Golden Horn Racing Post the Nile) can enter the annals the specialist miler of history as the 3-5 favorite in Rebecca Sharp (GB) (Machiavellian) sitting alongside the Saturday=s >Test of the Champion= on Long Island. -

An Overview of Working Conditions in Sportswear Factories in Indonesia, Sri Lanka & the Philippines

An Overview of Working Conditions in Sportswear Factories in Indonesia, Sri Lanka & the Philippines April 2011 Introduction In the final quarter of 2010 the ITGLWF carried for export to the EU and North America, and out research in major sportswear producer many of those in the Philippines are also countries to examine working conditions in exporting to Japan. factories producing for multinational brands and retailers such as adidas, Dunlop, GAP, Greg Collectively the 83 factories employed over Norman, Nike, Speedo, Ralph Lauren and 100,000 workers, the majority of whom were Tommy Hilfiger (for a full list of the brands females under the age of 35. This report con- and retailers please see Annex 1). tains an executive summary of the findings, based on information collected from workers, The researchers collected information on work- factory management, supervisors, human ing conditions at 83 factories, comprising 18 resource staff and trade union officials. factories in Indonesia, 17 in Sri Lanka and 47 in the Philippines. In Indonesia researchers focused The research was carried out by the ITGLWF’s on 5 key locations of sportswear production: Bekasi, Bogor, Jakarta, Serang and Tangerang. affiliates in each of the target countries, in In Sri Lanka researchers examined conditions some cases with the assistance of research in the major sportswear producing factories, institutes. The ITGLWF would like to express mainly located in Export Processing Zones, and our gratitude to the Free Trade Zones and in the Philippines researchers focused on the General Services Employees Union, the National Capital Region, Region III and Region ITGLWF Philippines Council, Serikat Pekerja IV-A. -

AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL of TRADE MARKS 3 March 2011

Vol: 25, No. 9 3 March 2011 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it on our website (www.ipaustralia.gov.au) by using the "Journals" link on the home page. The Australian Official Journal of Trademarks is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 3 March 2011 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes. 2665 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed. 2665 Applications for Extension of Time . 2665 Applications for Amendment . 2665 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection . 2338 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1407400 to 1408941. 2317 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed. 2666 Withdrawn. 2667 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission Matters Initial Assessment Given by the ACCC. 2669 Cancellations of Entries in Register . 2669 Corrigenda . 2672 Notices . 2664 Opposition Proceedings . 2662 Removal/Cessation of Protection for Non-use Proceedings . 2670 Renewal of Registration/IR . 2670 Trade Marks Registered/Protected . 2662 Trade Marks Removed from the Register/IRs Expired . 2671 This Page Left Intentionally Blank For Information on the following please see our website: www.ipaustralia.gov.au or contact our Customer Service Network on 1300651010 Editorial enquiries Contact information Freedom of Information ACT Professional Standards Board Sales Requests for Information under Section 194 (c) Country Codes Trade Mark and Designs Hearing Sessions INID (Internationally agreed Numbers for the Indentification of Data) ‘INID’ NUMBERS in use on Australian Trade Mark Documents ‘INID’ is an acronym for Internationally agreed Numbers for the Identification of Data’ (200) Data Concerning the Application. -

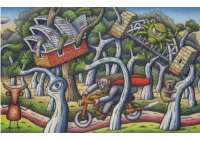

Selected Artworks by Chris O'doherty Aka Reg Mombassa Viewing By

SELECTED ARTWORKS BY CHRIS O’DOHERTY AKA REG MOMBASSA VIEWING BY APPOINTMENT ONLY Christopher O’Doherty, also known as Reg Mombassa, is an Australian musician and artist. He is known for his membership in bands Mental as Anything, Dog Trumpet and The Pinks. He worked with Mambo Graphics designing T-shirts and posters since 1986 and exhibited paintings, drawings and prints at Watters Gallery from 1975 to 2018. Beneath the humour in his work lies the expression of serious insights and sympathies. O’Doherty’s oeuvre is shaped from allegorical landscapes that create lingering, enigmatic sensations to both invite and unsettle his audience. His depictions of the familiar Australian landscape are imbued with an atmosphere of the immaterial to build a soft pulsing anticipation and gnawing stillness within his work. In the words of Australian art historian Chris McAuliffe, “In O’Doherty’s hands, every horizon hides an unreachable place where we long to be, every hillside implies an opposing slope that we’ll never know”. His diverse range of projects also includes taking part in solo and group art shows in Australia, New Zealand, Italy, USA, France, Britain, China and Thailand. He has had a survey show at the S.H. Ervin gallery in 2007 and Manly Gallery and Museum in 2018 with his brother Peter O'Doherty. His designs were featured in the Closing Ceremony of the Sydney Olympic Games in 2000, and he designed the graphics for the 2013 Sydney New Year’s Eve celebrations. In 2001 the Victorian Tapestry Workshop invited Reg to contribute a design for a 2 metre square section of a 43.5 metre long Federation Tapestry to be completed and installed in the Melbourne Museum.