Fashion's Influence on Garment Mass Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Uni Musos Struttin' at Australian Fashion Week USU

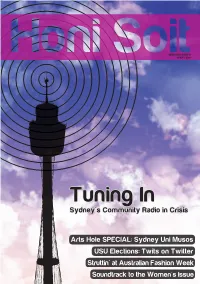

SEMESTER 1 WEEK 10 12 MAY, 2010 Tuning In Sydney's Community Radio in Crisis Arts Hole SPECIAL: Sydney Uni Musos USU Elections: Twits on Twitter Struttin' at Australian Fashion Week Soundtrack to the Women's Issue 2 This Week's: Smoke-free days: five. Swedish snack most likely to tear the editingCONTENTS team apart: Salt Sill Original With more quokkas Worst/bestthan question asked by an editor this week: “Sibella, will your recreational libraries HONI SOIT, EDITION 9 cater to the boom in 3D movies?” - Joe Smith-Davies, Manning Soapbox 12 MAY 2010 ever before. Most divisive pun: “Rob Chiarella learns that good art cums on small packages.” Thing that’s not as awesome as it sounds: turning off a computer with a hammer. The Post 03 The Arts-Hole 10 Letter rip, potato chip. SPECIAL EDITION: Jess Stirling, Jacinta Mulders, Bridie Connellan and Joe Payten catch up with our uni’s finest The Uni-Cycle 04 musical exports to talk sounds, Sydney and Zahra Anver thinks the answer is fairly obvious. the spotlight. Rob Chiarella learns that good art comes on small packages. The Mains 12 AA makes Oli Burton go AAAAAH! Daniel Zwi pricks his ears to a crisis in Tom Clement goes AAAAAH regarding AA. community radio. Carmen Culina thinks something’s fishery. To market, to market, for Chelsea Tabart. 05 The Lodgers 14 Ted Talas keeps it fResh. David Mack and Naomi Hart deliver 06 Women’s Honi was music to Joe Payten’s Honi’s final election rumours (and have the ears. decency to publish their names). -

Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art

School of Media Creative Arts and Social Inquiry (MCASI) Imaginary Aesthetic Territories: Australian Japonism in Printed Textile Design and Art Kelsey Ashe Giambazi This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University July 2018 0 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Date: 15th July 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely express my thanks and gratitude to the following people: Dr. Ann Schilo for her patient guidance and supervisory assistance with my exegesis for the six-year duration of my candidacy. To learn the craft of writing with Ann has been a privilege and a joy. Dr. Anne Farren for her supervisory support and encouragement. To the staff of the Curtin Fashion Department, in particular Joanna Quake and Kristie Rowe for the daily support and understanding of the juggle of motherhood, work and ‘PhD land’. To Dr. Dean Chan for his impeccably thorough copy-editing and ‘tidying up’ of my bibliographical references. The staff in the School of Design and Art, in particular Dr. Nicole Slatter, Dr. Bruce Slatter and Dr. Susanna Castleden for being role models for a life with a balance of academia, art and family. My fellow PhD candidates who have shared the struggle and the reward of completing a thesis, in particular Fran Rhodes, Rebecca Dagnall and Alana McVeigh. -

AN EXAMINATION of VANCOUVER FASHION WEEK by Vana Babic

AN EXAMINATION OF VANCOUVER FASHION WEEK by Vana Babic Bachelor of Arts in Political Science, European Studies, University of British Columbia, 2005 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Faculty of Business Administration © Vana Babic 2009 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2009 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Vana Babic Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: An Examination of Vancouver Fashion Week Supervisory Committee: ________________________________________ Dr. Michael Parent Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Faculty of Business Administration ________________________________________ Dr. Neil Abramson Second Reader Associate Professor of International Strategy Faculty of Business Administration Date Approved: ________________________________________ ii Abstract This study proposes a close examination of Vancouver Fashion Week, a biannual event held in Vancouver, showcasing local and international talent. It is one of the many Fashion Weeks held globally. Vancouver Fashion Week can be classified in the tertiary market in terms of coverage and designers showcased. The goal of these fashion shows is to connect buyers, including but not limited to boutiques, department stores and retail shops, with designers. Another goal is to bring media awareness to future trends in fashion. The paper will begin with an introduction to Fashion Weeks around the world and will be followed by an industry analysis. -

Lucire August 2004

Gabriel Scarvelli One designer can change the world august 2004 American idol The true idol look A light exists in spring Bronzing The gap Regardless of the between seasons season The circuit Cocktails Hot o\ the in London catwalks at The trendiest Sydney, Toronto, Los Angeles, Miami bars in town Hilary Permanent Rowland make-up Model We expose the businesswoman dangers juicy style 0 8 GST The global fashion magazine | www.lucire.com incl. http://lucire.com 1175-7515 1 $9·45 NZ ISSN 9 7 7 1 1 7 5 5 7 5 1 0 0 THIS MONTH THIS Volante travel now | feature Sail of the century You had the spring to spend time with the family. Now it’s the northern summer, the cruise lines are banking on self-indulgence being the order of the day compiled by Jack Yan far left: Fine dining aboard the Holland American Line. above left and above: Sophia Loren, godmother to the MSC Opera, accompanied by Capts Giuseppe Cocurullo and Gianluigi Aponte. left: The new KarView monitor. hold as many as 1,756 guests. The two pools, two hydro-massages and internet café are worthy of mention. Meanwhile, Crystal Cruises is announc- ing theme cruises for those who wish to ast month, it was about families. This ready amazing menu offering. Other signature indulge their passion while getting away. The month, it’s about luxurious self-indulgence entrées include chicken marsala with Wash- company highlights: ‘Garden Design sailings as the summer sailing season begins. As ington cherries and cedar planked halibut with through the British Isles; a Fashion & Style Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 sailed in to New Alaskan king crab. -

Australian Fashion Week's Trans-Sectoral Synergies

Beyond 'Global Production Networks': Australian Fashion Week's Trans-Sectoral Synergies This is the Published version of the following publication Weller, Sally Anne (2008) Beyond 'Global Production Networks': Australian Fashion Week's Trans-Sectoral Synergies. Growth and Change, 39 (1). pp. 104-122. ISSN 0017-4815 The publisher’s official version can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.2007.00407.x Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/4041/ Citation: Weller, S.A. (2008). Beyond "Global Production Network" metaphors: Australian Fashion Week's trans-sectoral synergies. Growth and Change, 39(1):104-22. Beyond “Global Production Networks”: Australian Fashion Week’s Trans-sectoral Synergies Sally Weller Centre for Strategic Economic Studies Victoria University PO Box 12488 Melbourne, Australia Ph +613 9919 1125 [email protected] Beyond “Global Production Networks”: Australian Fashion Week’s Trans-sectoral Synergies Sally Weller* ABSTRACT When studies of industrial organisation are informed by commodity chain, actor network or global production network theories and focus on tracing commodity flows, social networks or a combination of the two, they can easily overlook the less routine trans-sectoral associations that are crucial to the creation and realisation of value. This paper shifts attention to identifying the sites at which diverse specialisations meet to concentrate and amplify mutually reinforcing circuits of value. These valorisation processes are demonstrated in the case of Australian Fashion Week, an event in which multiple interests converge to synchronize different expressions of fashion ideas, actively construct fashion markets and enhance the value of a diverse range of fashionable commodities. -

Philip Treacy Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PHILIP TREACY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip Treacy,Marion Hume | 312 pages | 13 Oct 2015 | Rizzoli International Publications | 9780847846504 | English | New York, United States Philip Treacy PDF Book In a July interview with The Guardian , Treacy distilled what he felt a hat should do a Treacy quote which is often reproduced : [29]. There was a lot of Philip Treacy. Hildebrand, ". Connect with us. She worked as a nurse in London and used to come home on holidays with all these great magazines like Harper's and Queen and Vogue, which I'd never seen. I like hats that make the heart beat faster. Treacy is gay and in May he married his long-term partner of over 21 years, Stefan Bartlett, in a ceremony in Las Vegas. Blow would wear and promote Treacy's designs at important fashion events and helped Treacy to break into some of the main fashion houses, particularly Chanel and Givenchy. In , Treacy was discovered and then mentored by fashion editor Isabella Blow , whom Treacy described as the "biggest inspiration" on his life. Wikimedia Commons. Published: 8 May Philip Treacy. Milano: Charta. Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, chose a stunning headpiece by Philip Treacy for the wedding. Pretzels, switchboards and faux fur: the royals' most controversial hats. One of the world's foremost hat designers. Tickets Info Backstage. It moves me still. The Standard. Hats on: London statues get makeover. Hoboken: Wiley. Victoria and Albert Museum. Head and shoulders above. Published: 6 Nov Philip Treacy Writer Jonathan Jones on art Hats off to the fine art of London fashion week. -

Wwdinternationaltrades

WWDINTERNATIONALTRADESHOWSSECTION II BOUNCINGThe economy is still the number-one topic in global trade showB circles,ACK as organizers say they’re starting to see their countries’ fortunes turn around. S E G IMA CHAPMAN/GETTY S. GARY BY PHOTO 2 WWD, WEDNESDAY, MAY 19, 2010 SECTION II INTERNATIONAL TRADE SHOWS Premiere Classe/Who’s Next in January. AITRE M DOMINIQUE BY Outlook Brightens in City of Light PHOTO By Katya Foreman and Joelle Diderich anticipate, the fashion evolution of our exhibitors,” said Scherpe. For its sixth edition, running June 2 to 3, Denim by Première Vision will move PARIS — Salon organizers here cited a sharp uptick in applications for exhibition to a more central Paris location at the Halle Freyssinet, in the city’s 13th ar- space from quality brands and producers for the coming sessions, which they hope rondissement. The event has introduced a Future Denim Designers Award under indicates a parting of clouds. the aegis of denim guru Adriano Goldschmied. Supervised by Rad Rags’ Umberto “It’s another sign that the market is picking up,” said Philippe Pasquet, chief Brochetto, a group of students from London’s Central Saint Martins school will executive officer of Première Vision, which has trimmed the duration of its fall compete for the award. session to three days from four, running Sept. 14 to 16, to better reflect visitors’ Among new kids in town, Designers & Agents, which holds seasonal shows in compressed agendas. Los Angeles and New York, will launch its first Paris edition this fall. Dubbed D&A Pasquet said the aim was to optimize the textile salon’s organization as a com- Paris, it will bring a select crop of American brands. -

To Download the Power Top

14 OCTOBER 2017 THE POWER 30 WWW.RAGTRADER.COM.AU WWW.RAGTRADER.COM.AU THE POWER 30 OCTOBER 2017 15 PRESENTED BY PRESENTED BY merce vendor Styletread. "The new deal triples our turnover and more than triples CARLY CAZZOLLI our retail footrpint by 195 stores to 290," As the head of Asos Australia and New Munro said of the acquisition. It will also Zealand, Carly Cazzolli holds serious pull- boost annual sales by almost $200 mil- ing power in the eCommerce space. In The Power lion to $300 million, marking a landmark recent times, her team has scored major 30 moment for the footwear family empire. regional wins including free returns and There are rumours an IPO could be next price rationalisation for local customers. PIP EDWARDS on the agenda. “Being part of a global trading team adds a Sass & Bide, Ksubi, General Pants GUY RUSSO richness to the role that I really enjoy,” she Co. Pip Edwards has had creative He was the man who brought Kmart Aus- says. Prior to her role with Asos, Cazzolli input in some of the country’s most tralia back from the brink of bankruptcy, ERIN DEERING was the head of eCommerce for RM Wil- influential fashion brands, culmi- increasing profits by 100% within two In 2012, Erin Deering and Craig Ellis liams and currently sits on the National nating in the launch of her own years of taking the top job. His new man- turned traditional retailing on its head Online Retailers Association board. athleisure venture P.E Nation in date? Work the same magic for ailing sister when they launched swimwear brand Tri- 2016. -

Tuesday, February 12, 2013 Women's Wear Daily $3.00

WWD TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2013 Q WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY Q $3.00 Available at: 68 Greene Street - Soho | 5th Ave. at 54th Street NEW YORK WOMAN EVA MENDES WWD MILESTONES TO DO LINE FOR DENNIS BASSO AT 30. SECTION II NEW YORK & CO. PAGE 4 POP-UP STRATEGY Dior In Major Push Of Raf Simons’ Line By MILES SOCHA PARIS — Raf Simons’ fi rst collection for Dior is arriv- WWD ing at retail this month, accompanied by fanfare on a global scale. Dior is orchestrating a series of pop-up shops with TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2013 Q WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY Q $3.00 key wholesale partners in the coming weeks, trans- planting the decor and atmosphere of Simons’ ready- to-wear show in Paris last September to retailers in- cluding Joyce in Hong Kong, 10 Corso Como in Milan, Maxfi eld in Los Angeles, Isetan in Tokyo, My Boon in Seoul and I.T. in Beijing. “This is a new New Look,” declared Dior chief ex- ecutive Sidney Toledano, referring to the extravagant, fan-skirted silhouette that catapulted the French house to international fame in 1947 — and to Simons’ critically acclaimed reinterpretation of the founder’s legacy. Green Toledano cited a groundswell of excitement among buyers for Dior’s new artistic director of women’s haute couture, rtw and accessory collections, and a desire to animate Simons’ debut effort’s arrival in stores. “We had a lot of demand, and we didn’t want to be everywhere,” Toledano said in an interview. Spanning window displays, special furnishings, Light photo exhibitions and even a playlist of electronic music by French DJ Michel Gaubert, the installa- With a Forties heroine on her tions — some measuring several hundred square mind, Carolina Herrera sent out feet — are slated to last for up to three weeks. -

Africa's Influence in the Fashion Industry

Africa’s influence in the fashion industry By Marion Hume Published: June 12 2010 00:48 | Last updated: June 12 2010 00:48 Covetable Autumn/winter 2010 designs by (from left) Kenzo, Diane von Furstenberg, Gucci, Paul Smith, Lanvin A long way from the World Cup epicentres of Johannesburg and Durban, catwalkers in New York and Paris are already marching to an African beat. And why not? If global business will have its eye on all things African this month, chiming with the prevailing mood makes economic as well as sartorial sense. The work of Nigerian-born, London-based Duro Olowu, for instance, combines vintage couture fabrics and silhouettes with African prints (Princess Caroline of Monaco wore an Olowu evening gown at the Bal de la Rose – an annual event in Monaco attended by the royal family – in March). “What’s interesting,” Olowu says, “is the level of sophistication, which reflects the way African people have always combined European fabrics with indigenous culture. For a long time, there was a sense that this was limited to Africa but now it has become global. Combined with an awareness of social responsibility, it makes for a powerful statement.” Fashion’s big hitters are interested. Diane von Furstenberg has created a “tribal tattoo desert sugar” wrap dress for summer; Dries Van Noten has used Ikat fabrics from Lamu and Zanzibar with abandon; and Alber Elbaz showed fierce feather and bead neckpieces at Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2010 show in March. But there is more going on here than simple visual pillaging for mood board inspiration. -

Fashioned from Nature: Addressing Sustainable Fashion in a Museum of Art and Design

Fashioned from Nature Edwina Ehrman Fashioned from Nature: addressing sustainable fashion in a museum of art and design Edwina Ehrman Senior Curator, Victoria and Albert Museum, London [email protected] Abstract: This article draws on the author’s experience of curating Fashioned from Nature, an award-winning fashion exhibition which argues that sustainability should be embedded in design practice. Spanning approximately 350 years the exhibition shows how fashion’s environmental impact has grown to become a cause of international concern and activism. It highlights indivi- duals and organisations campaigning for change and the work of designers, scientists and educa- tors working within the field of sustainability. Its outcomes include an active network of contacts in academia, industry and politics and a deeper engagement with sustainable development within the host museum. Keywords: Sustainable fashion; raw materials; nature; environment; activism Resumen: El artículo presenta el trabajo de la autora como comisaria de la premiada exposición Fashioned from Nature, que defendía la necesidad de incorporar la sostenibilidad en el diseño de moda. La exposición partía de un enfoque histórico: empezaba 350 años antes para mostrar cómo había crecido el impacto ambiental de la moda hasta convertirse en causa de preocupación y activismo internacional. Además, ponía de relieve a las personas y organizaciones que luchan por este cambio y el trabajo de diseñadores, científicos y educadores en el campo de la sosteni- bilidad. Entre sus resultados, cabe destacar una activa red de contactos en el mundo académico, de la industria y la política, y un mayor compromiso con el desarrollo sostenible por parte del museo organizador. -

The Law, Culture, and Economics of Fashion

THE LAW, CULTURE, AND ECONOMICS OF FASHION C. Scott Hemphill* & Jeannie Suk** Forthcoming, Stanford Law Review (2009) INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 102! I. WHAT IS FASHION? ............................................................................................. 109! A. Status ........................................................................................................... 109! B. Zeitgeist ....................................................................................................... 111! C. Copies Versus Trends .................................................................................. 113! D. Why Promote Innovation in Fashion? ........................................................ 115! II. A MODEL OF TREND ADOPTION AND PRODUCTION ........................................... 117! A. Differentiation and Flocking ....................................................................... 118! B. Trend Adoption ............................................................................................ 119! C. Trend Production ........................................................................................ 121! III. HOW UNREGULATED COPYING THREATENS INNOVATION ............................... 123! A. Fast Fashion Copyists ................................................................................. 124! B. The Threat to Innovation ............................................................................. 127! 1.