A Simple Ikat Sash from Southern Okinawa: Symbol of Island Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada

Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada To cite this version: Thomas Pellard, Masahiro Yamada. Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni). Kiefer, Ferenc; Blevins, James P.; Bartos, Huba. Perspectives on morphological organization: Data and analyses, Brill, pp.31-49, 2017, 9789004342910. 10.1163/9789004342934_004. hal-01493096 HAL Id: hal-01493096 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01493096 Submitted on 20 Mar 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Kiefer, Ferenc & Blevins, James P. & Bartos, Huba (eds,), Perspectives on morphological organization: Data and analyses, 31–49. Leiden: Brill. isbn: 9789004342910. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004342934. chapter 2 Verb morphology and conjugation classes in Dunan (Yonaguni) Thomas Pellard and Masahiro Yamada 1 Dunan and the other Japonic languages 1.1 Japanese and the other Japonic languages Most Japonic languages have a relatively simple and transparent morphology.1 Their verb morphology is usually characterized by a highly agglutinative struc- ture that exhibits little morphophonology, with only a few conjugation classes and a handful of irregular verbs. For instance, Modern Standard Japanese has only two regular conjugation classes: a consonant-stem class (C) and a vowel- stem class (V). -

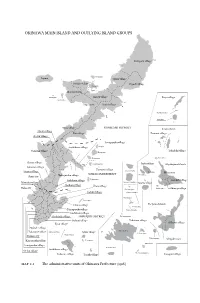

Okinawa Main Island and Outlying Island Groups

OKINAWA MAIN ISLAND AND OUTLYING ISLAND GROUPS Kunigami village Kourijima Iejima Ōgimi village Nakijin village Higashi village Yagajijima Ōjima Motobu town Minnajima Haneji village Iheya village Sesokojima Nago town Kushi village Gushikawajima Izenajima Onna village KUNIGAMI DISTRICT Kerama Islands Misato village Kin village Zamami village Goeku village Yonagusuku village Gushikawa village Ikeijima Yomitan village Miyagijima Tokashiki village Henzajima Ikemajima Chatan village Hamahigajima Irabu village Miyakojima Islands Ginowan village Katsuren village Kita Daitōjima Urasoe village Irabujima Hirara town NAKAGAMI DISTRICT Simojijima Shuri city Nakagusuku village Nishihara village Tsukenjima Gusukube village Mawashi village Minami Daitōjima Tarama village Haebaru village Ōzato village Kurimajima Naha city Oki Daitōjima Shimoji village Sashiki village Okinotorishima Uozurijima Kudakajima Chinen village Yaeyama Islands Kubajima Tamagusuku village Tono shirojima Gushikami village Kochinda village SHIMAJIRI DISTRICT Hatomamajima Mabuni village Taketomi village Kyan village Oōhama village Makabe village Iriomotejima Kumetorishima Takamine village Aguni village Kohamajima Kume Island Itoman city Taketomijima Ishigaki town Kanegusuku village Torishima Kuroshima Tomigusuku village Haterumajima Gushikawa village Oroku village Aragusukujima Nakazato village Tonaki village Yonaguni village Map 2.1 The administrative units of Okinawa Prefecture (1916) <UN> Chapter 2 The Okinawan War and the Comfort Stations: An Overview (1944–45) The sudden expansion -

Pictures of an Island Kingdom Depictions of Ryūkyū in Early Modern Japan

PICTURES OF AN ISLAND KINGDOM DEPICTIONS OF RYŪKYŪ IN EARLY MODERN JAPAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ART HISTORY MAY 2012 By Travis Seifman Thesis Committee: John Szostak, Chairperson Kate Lingley Paul Lavy Gregory Smits Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter I: Handscroll Paintings as Visual Record………………………………. 18 Chapter II: Illustrated Books and Popular Discourse…………………………. 33 Chapter III: Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei: A Case Study……………………………. 55 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………. 78 Appendix: Figures …………………………………………………………………………… 81 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………………………………. 106 ii Abstract This paper seeks to uncover early modern Japanese understandings of the Ryūkyū Kingdom through examination of popular publications, including illustrated books and woodblock prints, as well as handscroll paintings depicting Ryukyuan embassy processions within Japan. The objects examined include one such handscroll painting, several illustrated books from the Sakamaki-Hawley Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library, and Hokusai Ryūkyū Hakkei, an 1832 series of eight landscape prints depicting sites in Okinawa. Drawing upon previous scholarship on the role of popular publishing in forming conceptions of “Japan” or of “national identity” at this time, a media discourse approach is employed to argue that such publications can serve as reliable indicators of understandings -

Effects of Constructing a New Airport on Ishigaki Island

Island Sustainability II 181 Effects of constructing a new airport on Ishigaki Island Y. Maeno1, H. Gotoh1, M. Takezawa1 & T. Satoh2 1Nihon University, Japan 2Nihon Harbor Consultants Ltd., Japan Abstract Okinawa Prefecture marked the 40th anniversary of its reversion to Japanese sovereignty from US control in 2012. Such isolated islands are almost under the environment separated by the mainland and the sea, so that they have the economic differences from the mainland and some policies for being active isolated islands are taken. It is necessary to promote economical measures in order to increase the prosperity of isolated islands through initiatives involving tourism, fisheries, manufacturing, etc. In this study, Ishigaki Island was considered as an example of such an isolated island. Ishigaki Island is located to the west of the main islands of Okinawa and the second-largest island of the Yaeyama Island group. Ishigaki Island falls under the jurisdiction of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, which is situated approximately half-way between Kyushu and Taiwan. Both islands belong to the Ryukyu Archipelago, which consists of more than 100 islands extending over an area of 1,000 km from Kyushu (the southwesternmost of Japan’s four main islands) to Taiwan in the south. Located between China and mainland Japan, Ishigaki Island has been culturally influenced by both countries. Much of the island and the surrounding ocean are protected as part of Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park. Ishigaki Airport, built in 1943, is the largest airport in the Yaeyama Island group. The runway and air security facilities were improved in accordance with passenger demand for larger aircraft, and the airport became a tentative jet airport in May 1979. -

Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’S University, Too [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 9-2014 Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano Nara Women’s University, [email protected] Yuka Matsumoto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Art Practice Commons Sano, Toshiyuki and Matsumoto, Yuka, "Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands" (2014). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 885. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/885 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Changes in the Way of Traditional Cloth Makings and the Weavers’ Contribution in the Ryukyu Islands Toshiyuki Sano and Yuka Matsumoto This article is based on a fieldwork project we conducted in 2013 and 2014. The objective of the project was to grasp the current state of how people are engaged in the traditional ways of weaving, dyeing and making cloth in the Ryukyu Islands.1 Throughout the project, we came to think it important to understand two points in order to see the direction of those who are engaged in manufacturing textiles in the Ryukyu Islands. The points are: the diversification in ways of engaging in traditional cloth making; and the importance of multi-generational relationship in sustaining traditional cloth making. -

Tanedori of Taketomi Island: Intergenerational Transmission of Intangible Heritage

Tanedori of Taketomi Island: Intergenerational Transmission of Intangible Heritage. Goya Junko Tanedori of Taketomi Island: Intergenerational Transmission of Intangible Heritage. Tanedori of Taketomi Island: Intergenerational Transmission of Intangible Heritage. Goya Junko Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Nagoya University ABSTRACT This paper examines performing arts as Intangible Cultural Properties, and considers their transmission, focusing on the case of Tanedori of Taketomi Island (hereafter Tanedori) one of the Important Intangible Folk- cultural Properties of Taketomi-cho in Okinawa Prefecture. In particular, it focuses on the importance of the mutual relationship between local communities and schools. Tanedori refers to the ritual of planting rice or millet. In the past this ritual was performed all over Okinawa Prefecture. Tanedori faces the same sort of challenges as many other intangible heritage activities - lack of people to carry on the tradition and a declining and aging local population. This paper provides a case study on the role schools can play, through the active engagement of teachers and principals with the local communities, in the transmission of ritual performances Keywords intergenerational transmission, performing arts, school education, Tanedori. Introduction The declining and aging population in Japan is Tanedori is a ritual for sowing seeds of rice and millet endangering many arts designated as intangible cultural and praying for a good harvest. This event was held in assets due to lack of people to carry on the traditions. In several places in Okinawa in the past. Today Taketomi recent years, it has become so vital to safeguard the Island has one of the best safeguarded Tanedori. -

Higashi Village

We ask for your understanding Cape Hedo and cooperation for the environmental conservation funds. 58 Covered in spreading rich green subtropical forest, the northern part of 70 Okinawa's main island is called“Yanbaru.” Ferns and the broccoli-like 58 Itaji trees grow in abundance, and the moisture that wells up in between Kunigami Village Higashi Convenience Store (FamilyMart) Hentona Okinawa them forms clear streams that enrich the hilly land as they make their way Ie Island Ogimi Village towards the ocean. The rich forest is home to a number of animals that Kouri Island Prefecture cannot be found anywhere else on the planet, including natural monu- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium Higashi Nakijin Village ments and endemic species such as the endangered Okinawa Rail, the (Ocean Expo Park) Genka Shioya Bay Village 9 Takae Okinawan Woodpecker and the Yanbaru Long-Armed Scarab Beetle, Minna Island Yagaji Island 331 Motobu Town 58 Taira making it a cradle of precious flora and fauna. 70 Miyagi Senaga Island Kawata Village With its endless and diverse vegetation, Yanbaru was selected as a 14 Arume Gesashi proposed world natural heritage site in December 2013. Nago City Living alongside this nature, the people of Yanbaru formed little settle- 58 331 ments hugging the coastline. It is said that in days gone by, lumber cut Kyoda I.C. 329 from the forest was passed from settlement to settlement, and carried to Shurijo Castle. Living together with the natural blessings from agriculture Futami Iriguchi Cape Manza and fishing, people's prayers are carried forward to the future even today Ginoza I.C. -

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” Under the Japan-U.S

Militarization and Demilitarization of Okinawa As a Geostrategic “Keystone” under the Japan-U.S. Alliance August 10-12, 2013 International Geographical Union (IGU) 2013 Kyoto Regional Conference Commission on Political Geography Post-Conference Field Trip In Collaboration with Political Geography Research Group, Human Geographical Society of Japan and Okinawa Geographical Society Contents Organizers and Participants………………………………………………………………………….. p. 2 Co-organizers Assistants Supporting Organizations Informants Participants Time Schedule……………………………………………………………………………………….. p. 4 Route Maps……………………………………………………………………………………….…..p. 5 Naha Airport……………………………………………………………………………………….... p. 6 Domestic Flight Arrival Procedures Domestic Flight Departure Procedures Departing From Okinawa during a Typhoon Traveling to Okinawa during a Typhoon Accommodation………………………………………...…………………………………………..... p. 9 Deigo Hotel History of Deigo Hotel History of Okinawa (Ryukyu)………………………………………..………………………............. p. 11 From Ryukyu to Okinawa The Battle of Okinawa Postwar Occupation and Administration by the United States Post-Reversion U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa…………………………………………………………………...… p. 14 Futenma Air Station Kadena Air Base Camp Schwab Camp Hansen Military Base Towns in Okinawa………………………………………………………...………….. p. 20 Political Economic Profile of Selected Base Towns Okinawa City (formerly Koza City) Chatan Town Yomitan Village Henoko, Nago City Kin Town What to do in Naha……………………………………………………………………………...… p. 31 1 Organizers -

Study on Okinawa's Development Experience in Public Health

Study on Okinawa’s Development Experience in Public Health and Medical Sector December 2000 Institute for International Cooperation Japan International Cooperation Agency I I C J R 00-56 PREFACE Recent years have seen a new emphasis on "people-oriented development" through aid in the social development field. Cooperation in the public health and medical sector is becoming increasingly important within this context because of its contributions to physical well-being, which is the basis from which all human activities proceed. Nonetheless, infectious diseases that were long ago eradicated in developed countries are still rampant in developing countries, as are HIV/AIDS and other new diseases. Even those diseases that can be prevented or treated claim precious lives on a daily basis because of inappropriate education and medical care. The government of developing countries, donors, NGOs, and other organizations continue to work to rectify this situation and improve the health care levels of people in developing countries. Japan, as one of the world's leading donor countries, is expected both to improve the quality of its own aid and to take a leadership role in this sector. To help us in this effort, we referred to the history of health and medical care in postwar Okinawa Prefecture. Okinawa's experiences during postwar reconstruction contain many lessons that can be put to use in improving the quality of aid made available to developing countries. In the times immediately following World War II, the people in Okinawa were constantly threatened with contagion and disease due to a lack of medical facilities and personnel, including doctors. -

The Independence Movement on Okinawa, Japan. a Study on the Impact of US Military Presence

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies The independence movement on Okinawa, Japan. A study on the impact of US military presence. Bachelor Thesis in Japanese studies Spring 2017 Anton Lövgren Supervisor: Ingemar Ottosson Abstract Ryūkyū independence movement has ever since WWII been an actor working towards independence for the Ryūkyū islands. Since the Okinawa Reversion Agreement 1971 the military bases has been a topic for debate. In this research the influence of the American military bases and its personnel's behavior have on the independence movement is examined using a qualitative analysis method. Further, this research argues that the military bases have influenced independence movement to gain more momentum for autonomy on Okinawa between 2004-2017. Keywords Ryūkyū, Identity, Ryūkyū independence movement, American military bases, Collective identity. Acknowledgement I am so glad for all the encouragement and assistance I’ve been given by the department of Asian, Middle eastern and Turkish studies. Especially by my supervisor Ingemar Ottosson and course coordinator Christina Nygren. Romanisation of Japanese words and names Japanese words and names will be written with the Hepburn romanization system. Long vowels such as a e i o u will be written with a macron (ā ē ī ō ū). For example Ryūkyū (琉球) would otherwise be written with long vowels as ryuukyuu. Japanese names are traditionally written with family name and given name subsequently. This thesis will use the western standard i.e. given name first and family name second. For example Takeshi Onaga the governor of Okinawa Prefecture in Japan (In tradtional Japanese standard 翁 長 雄志 Onaga Takeshi). -

Coral Reefs of Japan

Yaeyama Archipelago 6-1-7 (Map 6-1-7) Province: Okinawa Prefecture Location: ca. 430 km southwest off Okinawa Island, including Ishigaki, Iriomote, 6-1-7-③ Kohama, Taketomi, Yonaguni and Hateruma Island, and Kuroshima (Is.). Features: Sekisei Lagoon, the only barrier reef in Japan lies between the southwestern coast of Ishigaki Island and the southeastern coast of Taketomi Island Air temperature: 24.0˚C (annual average, at Ishigaki Is.) Seawater temperature: 25.2˚C (annual average, at east off Ishigaki Is.) Precipitation: 2,061.1 mm (annual average, at Ishigaki Is.) Total area of coral communities: 19,231.5 ha Total length of reef edge: 268.4 km Protected areas: Iriomote Yonaguni Is. National Park: at 37 % of the Iriomote Is. and part of Sekisei Lagoon; Marine park zones: 4 zones in Sekisei 平久保 Lagoon; Nature Conservation Areas: Sakiyama Bay (whole area is designated as marine special zones as well); Hirakubo Protected Water Surface: Kabira and Nagura Bay in Ishigaki Is. 宇良部岳 Urabutake (Mt.) 野底崎 Nosokozaki 0 2km 伊原間 Ibarama 川平湾 Kabira Bay 6-1-7-① 崎枝湾 浦底湾 Sakieda Bay Urasoko Bay Hatoma Is. 屋良部半島 川平湾保護水面 Yarabu Peninsula Kabirawan Protected Water Surface ▲於茂登岳 Omototake (Mt.) 嘉弥真島 Koyama Is. アヤカ崎 名蔵湾保護水面 Akayazaki Nagurawan Protected Ishigaki Is. Water Surface 名蔵湾 Nagura Bay 竹富島タキドングチ 轟川 浦内川 Taketomijima Takedonguchi MP Todoroki River Urauchi River 宮良川 崎山湾自然環境保護地域 細崎 Miyara River Sakiyamawan 古見岳 Hosozaki 白保 Nature Conservation Area Komitake (Mt.) Shiraho Iriomote Is. 登野城 由布島 Kohama Is. Tonoshiro Yufujima (Is.) 宮良湾 Taketomi Is. Miyara Bay ユイサーグチ Yuisaguchi 仲間川 崎山湾 Nakama River 竹富島シモビシ Sakiyama Bay Taketomi-jima Shimobishi MP ウマノハピー 新城島マイビシ海中公園 Aragusukujima Maibishi MP Umanohapi Reef 6-1-7-② Kuroshima (Is.) 黒島キャングチ海中公園 上地島 Kuroshima Kyanguchi MP Uechi Is. -

Okinawa and Yonaguni

Subject : Ancient Scripts and Languages Article: 43 Okinawa and Yonaguni Doç. Dr. Haluk Berkmen In article 40-The Pacific Expansion (1) I have shown on the map that the Japanese islands were first inhabited about 6000 years before present. This period of time is when the OK tribes left their homeland of Central Asia and moved in every possible direction. It is during this period that the south-west expansion took place (2). Okinawa prefecture of Japan comprises a chain of islands known as the Ryukyu Islands. The oldest evidence of human existence on the Ryukyu Islands is from Stone Age and was discovered in Naha and Yaese (3). The Ryukyu kingdom was independent until 1609 and had a language quite different than Japanese. There remain six Ryukyuan languages which are incomprehensible to Japanese speakers, although they are considered to make up the family of Japonic languages along with Japanese. The name Okinawa can be split as OK-INA-WA . In Japanese inaka means “one’s home area or country”. It is quite possible that the ancient form of this word was ‘ ina ’ in the Ryukyuan language. WA on the other hand means “is” in general and is related to the Turkish word “var”, which took the form of ‘ aru ’ in Japanese. So, Okinawa means “This is the country of the OK tribe”. At the very south of the Ryukyu Islands we have Yonaguni as shown below. In 1986, local divers discovered a striking underwater rock formation off the southernmost point of the island. This so-called Yonaguni Monument has staircase-like terraces with flat sides and sharp corners.