V24n54a15.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014

Lanza, G. (Editor) Hauns, D.; Hochdörffer, J.; Peters, S.; Ruhrmann, S.: State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014 Shanghai Lanza, G. (Editor); Hauns, D.; Hochdörffer, J.; Peters, S.; Ruhrmann, S.: State of Automotive Technology in PR China - 2014 Institute of Production Science (wbk) Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) Global Advanced Manufacturing Institute (GAMI) Leading Edge Cluster Electric Mobility South-West Contents Foreword 4 Core Findings and Implications 5 1. Initial Situation and Ambition 6 Map of China 2. Current State of the Chinese Automotive Industry 8 2.1 Current State of the Chinese Automotive Market 8 2.2 Differences between Global and Local Players 14 2.3 An Overview of the Current Status of Joint Ventures 24 2.4 Production Methods 32 3. Research Capacities in China 40 4. Development Focus Areas of the Automotive Sector 50 4.1 Comfort and Safety 50 4.1.1 Advanced Driver Assistance Systems 53 4.1.2 Connectivity and Intermodality 57 4.2 Sustainability 60 4.2.1 Development of Alternative Drives 61 4.2.2 Development of New Lightweight Materials 64 5. Geographical Structure 68 5.1 Industrial Cluster 68 5.2 Geographical Development 73 6. Summary 76 List of References 78 List of Figures 93 List of Abbreviations 94 Edition Notice 96 2 3 Foreword Core Findings and Implications . China’s market plays a decisive role in the . A Chinese lean culture is still in the initial future of the automotive industry. China rose to stage; therefore further extensive training and become the largest automobile manufacturer education opportunities are indispensable. -

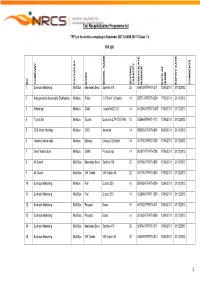

TRP Programme List July Revision 64

- 1 -Last saved by nthitemd - 1 -19 Taxi Recapitalization Programme list TRP List for vehicles complying to September 2007 & SANS 20107 Clause 7.6 TRP 2009 ISSUE DATE EXPIRY COMMENTS NO COMPANY CATEGORY NAME MODEL NAME SEATING CAPACITY CERTIFICATE NUMBER OF DATE 1 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 518 22 556739-TRP07-0311 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 2 Amalgamated Automobile Distributors Minibus Foton 2.2 Petrol 13 Seater 14 550713-TRP07-0309 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 3 Whallinger Minibus CAM Inyathi XGD 2.2i 14 541394-TRPO7-0609 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 4 Toyota SA Minibus Toyota Quantum 2.7P 15S TAXI 15 555664-TRP07-1110 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 5 CCE Motor Holdings Minibus CMC Amandla 14 550826-TRP07-0609 20/06/2011 31/12/2013 6 Nanfeng Automobile Minibus Ekhaya Ekhaya 2.2i Hatch 14 551700-TRP07-0709 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 7 Great Wall motors Minibus GWM Proteus Mpi 14 551517-TRP07-0709 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 8 Mr Coach Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 518 22 551798-TRP07-0809 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 9 Mr Coach Midi Bus VW Crafter VW Crafter 50 22 551799-TRP07-0809 17/06/2011 31/12/2013 10 Bustruck Marketing Minibus Fiat Ducato 250 16 551958-TRP07-0809 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 11 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Fiat Ducato 250 19 552898-TRP07-1209 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 12 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Peugeot Boxer 19 557082-TRP07-0411 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 13 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Peugeot Boxer 16 551959-TRP07-0809 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 14 Bustruck Marketing Midi Bus Mercedes Benz Sprinter 416 22 556740-TRP07-0311 13/06/2011 31/12/2013 15 -

China Autos Driving the EV Revolution

Building on principles One-Asia Research | August 21, 2020 China Autos Driving the EV revolution Hyunwoo Jin [email protected] This publication was prepared by Mirae Asset Daewoo Co., Ltd. and/or its non-U.S. affiliates (“Mirae Asset Daewoo”). Information and opinions contained herein have been compiled in good faith from sources deemed to be reliable. However, the information has not been independently verified. Mirae Asset Daewoo makes no guarantee, representation, or warranty, express or implied, as to the fairness, accuracy, or completeness of the information and opinions contained in this document. Mirae Asset Daewoo accepts no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any loss arising from the use of this document or its contents or otherwise arising in connection therewith. Information and opin- ions contained herein are subject to change without notice. This document is for informational purposes only. It is not and should not be construed as an offer or solicitation of an offer to purchase or sell any securities or other financial instruments. This document may not be reproduced, further distributed, or published in whole or in part for any purpose. Please see important disclosures & disclaimers in Appendix 1 at the end of this report. August 21, 2020 China Autos CONTENTS Executive summary 3 I. Investment points 5 1. Geely: Strong in-house brands and rising competitiveness in EVs 5 2. BYD and NIO: EV focus 14 3. GAC: Strategic market positioning (mass EVs + premium imported cars) 26 Other industry issues 30 Global company analysis 31 Geely Automobile (175 HK/Buy) 32 BYD (1211 HK/Buy) 51 NIO (NIO US/Buy) 64 Guangzhou Automobile Group (2238 HK/Trading Buy) 76 Mirae Asset Daewoo Research 2 August 21, 2020 China Autos Executive summary The next decade will bring radical changes to the global automotive market. -

Download Automotive Patent Trends 2019 – Technologies

A U T O M O T I V E P A T E N T T R E N D S 2 0 1 9 Cipher Automotive is the only patent intelligence software that includes a taxonomy of over 200 technologies critical to the future of the car AU T O M O T I V E @ C I P H E R . A I Cipher Automotive Patent Trends 2019 provides a strategic overview of patented technologies in Foreword the sector. Patent intelligence is critical at a time when there is an accelerating shifrom conventional technologies to connectivity, autonomy, shared services and electrification. It is not only the OEMs and their suppliers who are investing billions in automotive R&D, but an entire network of technology companies and a vast swathe of start-ups that are now able to participate at a time when barriers to entry have been lowered. These dynamics are placing increasing pressure on legal, intellectual property and R&D teams alike. We have now reached the point where there are over two million new patents published a year, and it is harder than ever to understand whether the patents you own are the ones that truly serve your business objectives. Advances in AI have made it possible to access information about who owns patented technology. The analysis of technologies and companies in the pages that follow were generated in less than 4 hours - by a machine that does not tire, drink coffee or take holidays. Nigel Swycher, CEO and Steve Harris, CTO This section covers nine technology areas within the automotive industry, identifies the top patent Section 1: owners, shows the growth of patenting, highlights a few important technologies within each area, and includes league tables across the major geographies. -

China Annex VI

Annex I. Relations Between Foreign and Chinese Automobile Manufacturers Annex II. Brands Produced by the Main Chinese Manufacturers Annex III. SWOT Analysis of Each of the Ten Main Players Annex IV. Overview of the Location of the Production Centers/Offices of the Main Chinese Players Annex V. Overview of the Main Auto Export/Import Ports in China Annex VI. An Atlas of Pollution: The World in Carbon Dioxide Emissions Annex VII. Green Energy Vehicles Annex VIII. Further Analysis in the EV vehicles Annex IX. Shifts Towards E-mobility Annex I. Relations Between Foreign and Chinese Automobile Manufacturers. 100% FIAT 50% Mitsubishi Guangzhou IVECO 50% Beijing Motors 50% Hyundai 50% GAC Guangzhou FIAT GAC VOLVO 91.94% Mitsubishi 50% 50% 50% 50% 50% (AB Group) Guangzhou BBAC 50% Hino Hino Dongfeng DCD Yuan Beiqi 50% 50% NAVECO Invest Dongfeng NAC Yuejin 50% Cumins Wuyang 50% Guangzhou GAC Motor Honda 50% Yuejin Beiqi Foton Toyota 50% Cumins DET 50% 55.6% 10% 20% 50% Beiqi DYK 100% Guangzhou Group Motors 50% 70% Daimler Toyota 30% 25% 50% 65% Yanfeng SDS shanghai 4.25% 100% 49% Engine Honda sunwin bus 65% 25% visteon Holdings Auto 50% (China) UAES NAC Guangzhou 50% Beilu Beijing 34% Denway Automotive 50% Foton 51% 39% motorl Guangzhou 50% Shanghai Beiqi Foton Daimler 100% 30% 50% VW BAIC Honda Kolben 50% 90% Zhonglong 50% Transmission 50% DCVC schmitt Daimler Invest 100% 10% Guangzhou piston 49% DFM 53% Invest Guangzhou Isuzu Bus 100% Denway Beiqi 33.3% Bus GTE GTMC Manafacture xingfu motor 50% 20% SAIC SALES 100% 20% 100% 100% DFMC 100% Shanghai -

The Way of Chery to Achieve the Most Successful Auto

THE WAY OF CHERY TO ACHIEVE THE MOST SUCCESSFUL AUTO BRAND IN CHINA Thesis Yan Tao Degree Programme in International Business International Marketing Management SAVONIA UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Business and Administration, Varkaus Degree Programme, Bachelor of Business Administration, International Business, International Marketing Management Author Yan Tao Title of Study The Way of Chery to Achieve the Most Successful Auto Brand in China Type of Project Date Pages Thesis 14.12.2010 62+3 Supervisor of Study Executive organization Virpi Oksanen Abstract The automobile market in China is in the state of growth. The development of new energy vehicles and the automobile industry is taking place in the forms of regrouping and restructuring. This offers Chery a great opportunity to develop and promote the brand. As one of the most influential and famous auto brand, Chery Auto has achieved an extraordinary growth rate and has become the pride of Chinese national automobile industry. Nevertheless, there is still certain potential in product quality, service and business culture which develops the brand image further. In consequence, issues regarding to manufacturing, service and business culture are needed to improve and strengthening. However, the brand advantage of Chery Auto is not protruding. Compared with international automotive corporations, Chery Auto is not dominant in brand recognition and brand core value. Furthermore, multi-brand strategy leads to dilution of major brands. There are many sub-brands under Chery; nevertheless, no sub-brand achieves big sales. None of Chery Auto’s four sub-brands, Chery, Rely, Karry or Riich, is dominant in the automobile market. Its position in market is not stable. -

P ASAJ E ROS Y MIX to CA RGA Tabla No. 1. CLASIFICACIÓN

MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE Tabla No. 1. CLASIFICACIÓN SEGÚN CLASE, TIPO Y MARCA PARA EL AÑO FISCAL 2011 MODALIDAD CLASE Y CARROCERIA GRUPO MARCA Aro, Asia, Austin, Barreiro, Baw, Bock Wall, Chana, Changfeng, Changhe, Dacia, Daewoo, Datsun, Desoto, Deutz, Dfm, Dragon, Ernest Gruber, Faw, Fiat, Forland, Foton, Golden Dragon, Goleen, GWM, Hafei, Hersa, Higer, Huali, Ifa, Jac, Jiangchan, F Jinbei, JMC, Kaizer, Kamaz, Kiamaster, Kraz, Land Rover, Man, Mudan, PH Omega, Tractocamiónes y Camionetas Ramírez, Reo, Saic, Sinotruck, Sisu, Skoda, Steyr, Studebaker, Tata, T-King, Tmd, y Camiónes con carrocería Uaz, Wartburg, White, Willco, Willys, World Star, Xinkai, Yutong, ZX Auto estacas, estibas, niñera, panel, picó, planchón, portacontenedor Agrale, Ample, Chevrolet, Citroen, Daihatsu, Dina, Delta, Dodge, Fargo, Ford, GMC, y reparto. Hino, Hyundai, Kia, International, Isuzu, Iveco, Honda, Magirus, Mazda, Mitsubishi, G Mercury, Nissan, Non Plus Ultra, Peugeot, Renault, Renno, Ssangyong, Schacman, Suzuki, Toyota, Volkswagen Freigthliner, Kenworth, Mack, Marmon, Mercedes Benz, Pegaso, Scania, Volvo y H Wester Star Aro, Asia, Austin, Barreiro, Baw, Bock Wall, Chana, Changfeng, Changhe, Dacia, Daewoo, Datsun, Desoto, Deutz, Dfm, Dragon, Ernest Gruber, Faw, Fiat, Forland, Foton, Golden Dragon, Goleen, GWM, Hafei, Hersa, Higer, Huali, Ifa, Jac, Jiangchan, I Jinbei, JMC, Kaizer, Kamaz, Kiamaster, Kraz, Land Rover, Man, Mudan, PH Omega, Camionetas, Camiónes con Ramírez, Reo, Saic, Sinotruck, Sisu, Skoda, Steyr, Studebaker, Tata, T-King, Tmd, Uaz, Wartburg, -

Asian Automotive Newsletter

ASIAN AUTOMOTIVE NEW SLETTER JUNE 2011, ISSUE 67 A Quarterly newsletter of developments in the auto and auto components markets Chinese companies are buying up assets offices in all of the major Asian across the Auto sector worldwide. Geely automotive markets, as well as London CONTENTSC O N T E N T S paid US$2.7bn for Volvo in 2010, Joyson and New York. If you are interested in agreed to buy Preh for US$721m in April, discussing any of the articles in this C H I N A 1 Beijing Auto announced plans to acquire newsletter, or how we can help you in H O N G K O N G 4 Inalfa Roof Systems for US$370m in this sector, please contact me directly. I N D I A 4 April, and Zhejiang Youngman and I N D O N E S I A 5 Pangda recently agreed to acquire Saab for US$250m. Expect China to continue J A P A N 5 hunting for foreign assets. K O R E A 5 Charles Maynard M A L A Y S I A 5 Business Development Asia LLC (“BDA”) Senior Managing Director, PHILIPPINES 5 is an investment banking firm which [email protected] specializes in Asian M&A. We have T A I W A N 5 China AutolivAutoliv, the Swedish auto component manufacturer, plans to invest US$10m in a new seat belt plant in Nanjing, China. The new plant will replace Auto Sector Stock Indices (12 months ending 27 Jun11 ))) Autoliv’s existing plant in the region and 210 will be 1.5 times larger than the existing plant. -

Research on Power Battery Full Life Cycle Asset Management

Research on Power Battery Full Life Cycle Asset Management (Annual Report of Power Battery Full Life Cycle Joint Innovation Center) December 2020 Foreword China EV100 is committed to becoming a high-level third-party think-tank for the industry of electric vehicles (EVs) and related fields in China, and conducting research is the top priority for building the think-tank. China EV100 mainly aims to create a platform, integrate internal and external resources, and organize professionals to conduct surveys and researches, so as to eventually form research reports that can be used as references for decision making. This Research Report was formulated based on interim research results and for internal reference only. Since it's not for public release, sources are not provided for the data cited, the viewpoints collected and the research evidences used for now. As some information is from external sources, and is not verified with the related enterprises one-by-one, if the analysis about some enterprises is inaccurate, the actual situation should prevail. Project Team Team Leader: Zhang Yongwei Deputy Team Leader: Xu Erman Members: Zhu Jin, Zhang Jian, Wang Xiaoxu, Yan Yancui, Li Songzhe (In no particular order) Acknowledgement Bao Wei, General Manager of Zhejiang Huayou Recycling Technology Co., Ltd. He Long, CEO of Findreams Battery (BYD) Co., Ltd. Jia Junguo, Level-3 Consultant of State Grid Electric Vehicle Service Co., Ltd. and Chairman of SEETIC Pan Fangfang, Deputy General Manager of China Lithium Battery Technology Co., Ltd. Sun He, Vice President of SK Innovation E-mobility Business Xu Zhibin, General Manager of ADI China Automotive Business Zhao Xiaoyong, General Manager of Beijing SDM Resource Recycling Research Institute Co., Ltd. -

The Lithium Ion Battery and the EV Market: the Science Behind What You Can’T See

The Lithium Ion Battery and the EV Market: The Science Behind What You Can’t See February 2018 Kimberly Berman Jared Dziuba, CFA Colin Hamilton Special Projects Analyst Oil & Gas Analyst Global Commodities Analyst BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. BMO Capital Markets Limited [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (416) 359-5611 (403) 515-3672 +44 (0)20 7664 8172 Richard Carlson, CFA Joel Jackson, P.Eng., CFA Peter Sklar, CPA, CA Autos/Mobility Equipment & Technology Analyst Fertilizers & Chemicals Analyst Auto Parts & Retailing/Consumer Analyst BMO Capital Markets Corp. BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (212) 885-4060 (416) 359-4250 (416) 359-5188 This report was prepared in part by analysts employed by a Canadian affiliate, BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc., and a UK affiliate, BMO Capital Markets Limited, authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK, and who are not registered as research analysts under FINRA rules. For disclosure statements, including the Analyst’s Certification, please refer to the back of this report. 17:00 ET~ Contributors KIMBERLY BERMAN JARED DZIUBA, CFA COLIN HAMILTON Special Projects Analyst Oil & Gas Analyst Global Commodities Analyst BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc. BMO Capital Markets Limited [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (416) 359-5611 (403) 515-3672 +44 (0)20 7664 8172 RICHARD CARLSON, CFA JOEL JacKSON, P.ENG., CFA PETER SKLAR, CPA, CA Autos/Mobility Equipment & Technology Analyst Fertilizers & Chemicals Analyst Auto Parts & Retailing/Consumer Analyst BMO Capital Markets Corp. -

Compilación De Disposiciones Aplicables Al MUNICIPIO DE MEDELLÍN N.D

RESOLUCIÓN 1458 DE 2013 (mayo 2) Diario Oficial No. 48.778 de 2 de mayo de 2013 MINISTERIO DE TRANSPORTE Por la cual se adiciona y ajusta a la tabla 1 anexa a la Resolución número 11177 del 30 de noviembre de 2012. LA MINISTRA DE TRANSPORTE, en ejercicio de las facultades legales, en especial de las conferidas por los artículos 143 de la Ley 488 de 1998, 6 numeral 6.4 y 15 numeral 15.6 del Decreto número 087 de 2011, y CONSIDERANDO: Que el Ministerio de Transporte mediante la Resolución número 11177 del 30 de noviembre de 2012, estableció la base gravable de los vehículos de carga y colectivo de pasajeros, para el año fiscal 2013. Que se han recibido comunicaciones de propietarios de vehículos solicitando la inclusión en la tabla 1 anexa a la Resolución 11177 de 2012, de la siguiente línea: Vehículos de Pasajeros Marca: Línea Chevrolet N300 Que se hace necesario ajustar en la Tabla número 1 Clasificación según Clase, Tipo y Marca para el año fiscal 2013, los cilindrajes de las camionetas de carga con carrocería tipo Picó en los grupos Y, Z. En mérito de lo expuesto, este Despacho, RESUELVE: ARTÍCULO 1o. Adicionar a la tabla 1, Clasificación según Clase, Tipo y Marca para el año fiscal 2013, anexa a la Resolución número 11177 de 2012, en el Grupo W la siguiente línea: Marca: Línea Chevrolet N300 ARTÍCULO 2o. Ajustar los cilindrajes en la tabla 1, Clasificación según Clase, Tipo y Marca para el año fiscal 2013, los grupos Y, Z, los cuales quedaran así: - Grupo Y: de 1401 cc hasta 2800cc. -

The Sustainability of Joint Ventures Between State Owned Enterprises And

Journal of Business and Economics, ISSN 2155-7950, USA April 2014, Volume 5, No. 4, pp. 462-483 DOI: 10.15341/jbe(2155-7950)/04.05.2014/004 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2014 http://www.academicstar.us The Sustainability of Joint Ventures between State Owned Enterprises and Global Firms for Car Making Business in China Byunghun Choi (Kongju National University, Korea) Abstract: Since 2009 China has kept the first place globally at the automobile production and the sales volume. The practical growth engine for China’s automobile industry is Joint Venture (JV) makers between State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and global makers which having concentrated on passenger car making business. The JVs’ role at the passenger car business of China has been expanded continuously since early 1990s. Chinese government has strictly prevented a foreign maker from holding above 50% of whole equity of a JV at vehicle making business. It means that the strategic alliances like non-equity alliances, equity alliances or JV have been feasible options for global makers to take for entering China’s vehicle making business. Therefore this study took a deep interest in how much sustainable the JV contracts in China, and tried to access the issues through industry based view and institution based view. At industry based view, this study analyzed which strategy is more desirable among three types of strategies; non-equity alliances, equity alliances and acquisitions. To do so this study applied the framework suggested by Dyer, Kale & Singh (2004) for deciding which strategy is relatively more suitable than others according to five factors; types of synergies, nature of resources, extent of redundant resources, degree of market uncertainty, and level of competition.