Of the 1932 Lake Placid Olympic Bobsled Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Vets Showed Athletic Prowess in Winter Olympics

War Vets Showed Athletic Prowess in Winter Olympics Jan 31, 2014 By Kelly Gibson The Winter Olympics are relatively young, appearing on the sporting scene for the first time in 1924. As early as 1928, though, war veterans participated. Here are a few of the better- known Olympian-vets among them. (Vets of the 10th Mountain Division who skied in the Olympics and biathlon vets are covered in separate articles.) Eddie P.F. Eagan (1897-1967) b. Denver, Colo. Eagan served stateside with the Artillery Corps during WWI, from July 4 to Dec. 28, 1918. However, during WWII, he saw service in the China-Burma-India and European theaters with the Army’s Air Transport Command. He served as chief of special services from May 13, 1942 until Sept. 30, 1944. As the only American to win a gold medal at both the Summer and Winter Olympics, Eagan showed natural athletic talent growing up. He is best known for his success as a boxer, winning titles in middle and heavyweight competitions. In 1919, he won the heavyweight title in the U.S. amateur championships as Yale’s boxing captain. Eagan, attending Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, became the first American amateur boxing champion of Great Britain. In 1920, Eagan participated in the Summer Olympics in Antwerp, where he won a gold medal in the lightweight boxing division. Despite having no experience with a bobsled, Eagan was invited to join the four-man team participating in the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid, N.Y., along with fellow veteran Billy Fiske. -

Winter Olympic Games As a Mega

TORINO 2006: AN ORGANISATIONAL AND ECONOMIC OVERVIEW by Piervincenzo Bondonio and Nadia Campaniello* Working paper n.1/2006 August 2006 * Since this work was conceived and produced jointly, acknowledgement for § 4 and 8 goes to Piervincenzo Bondonio, § 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 to Nadia Campaniello and to both authors for § 1 and 9. Financial support from Fondazione CRT, Progetto “Vittorio Alfieri” is gratefully acknowledged Abstract The Torino 2006 XX Winter Olympic Games have just ended, with results that the organisers and public opinion consider satisfactory on the whole. This article is a first attempt at analysing the Games, with an emphasis on the economic and organisational aspects. The basic question is: “What kind of Games were Torino 2006?”. To provide an answer, we have analysed the reasons behind the bid, the organisational model chosen, the economic scale of the event, and provided a detailed study of the scope of the standard objections to hosting the Games. The paper therefore aims to provide a contribution to the literature (still rather limited) about the Winter Olympics, whose growing size and profile justifies the need for a more careful, broader analysis. 2 Foreword In spite of the growing dimensions of the Olympic Games (“Citius Altius Fortius”), and the huge attention the media devote to them, there is a remarkable lack of reliable and consistent economic data about them. Furthermore, researchers have focused their studies more on the Summer than on the Winter Olympic Games (WOG), still perceiving the former as more prestigious and universal (Schantz, 2006, pp.49-53), although for recent Games the cost per inhabitant is even higher for the Winter Olympics (Preuss, 2004, p.33), which are becoming ever larger in terms of absorbed resources (Preuss, 2002a, p. -

Fall 2006.Qxp:Fall 2006

Official Publication of the: Volume 45 Number 3 Fall 2006 The American Connections with St. Paul’s REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM “DOME”• THE MAGAZINE OF THE FRIENDS OF ST. PAUL’S CATHEDRAL (LONDON), EDITION 43 Lay Canon Peter Chapman reports on the cleaning and restoration of the American Memorial Chapel and the service which followed he American connections Twith St. Paul’s go back many years. There are two visible signs of these. The first is the Memo- rial in the Crypt to Pilot Officer Billy Fiske who died in the Bat - tle of Britain. Billy was the first American pilot to die in the Allied cause, having told the recruiting officer he was Canadian! The second, of course, is the Ameri - can Memorial Chapel at the east end of the cathedral, behind the High Altar. The Chapel was consecrated by Her Majesty The Queen in 1958 and commemorates the lives of 28,000 Americans who died in the Second World War whilst based in Britain. It hous - es the Roll of Honor which lists the names of all 28,000 service people and was presented to the Cathedral, for perpetual safe keeping, by General Eisenhower at a service held on 24 July 1951. The Chapel had not yet been com menced then but the money for it had been raised entirely from the British people. The story of these events is record - ed in a beautiful pamphlet on sale in the Crypt Shop. Cleaning and restoration Turning to the present, it was originally considered unneces- sary to have the Chapel cleaned and restored as part of the mar- vellous renovation of the in side of the Cathedral. -

All Nations Together a Battle of Britain Resource

All Nations Together A Battle of Britain resource This resource provides biographical content to supplement a Key Stage 3 student study into the Battle of Britain. It highlights the international profile of the Royal Air Force in 1940. As well as investigation into the political, strategic, tactical and technical aspects of the battle, no study is complete without reference to the human experience of the event. This was an early phase of the Second World War when the outcome hung upon the skills and courage of a small number of combatants and support staff. It may surprise students to learn that numbered among Churchill’s ‘Few’ were participants from many Allied nations. A study of the Battle fits into Key Stage 3 History in the following ways: • In the broad purpose of the study of history, as outlined in the National Curriculum: ‘History helps pupils to understand the complexity of people’s lives, the process of change, the diversity of societies and relationships between different groups, as well as their own identity and the challenges of their time.’ • One of the key aims for the teaching of KS3 history is to: ‘know and understand the history of these islands as a coherent, chronological narrative, from the earliest times to the present day: how people’s lives have shaped this nation and how Britain has influenced and been influenced by the wider world.’ • Amongst options for subject content is the unit: ‘challenges for Britain, Europe and the wider world 1901 to the present day … this could include: … the Second World War and the wartime leadership of Winston Churchill.’ The Battle of Britain, 10 July to 31 October 1940, was a large air battle fought between the German air force - the Luftwaffe - and the Royal Air Force of Great Britain. -

Olympic Team Norway

Olympic Team Norway Media Guide Norwegian Olympic Committee NORWAY IN 100 SECONDS NOC OFFICIAL SPONSORS 2006 SAS Braathens Dagbladet TINE Adidas Clear Channel Adecco Head of state: If… H.M. King Harald V Telenor H.M. Queen Sonja Norsk Tipping Gyro gruppen PHOTO: SCANPIX Intersport Area (total): Norway 385.155 km2 - Svalbard 61.020 km2 - Jan Mayen 377 km2 Norway (not incl. Svalbard and Jan Mayen) 323.758 km2 NOC OFFICIAL SUPPLIERS 2006 Bouvet Island 49 km2 2 Peter Island 156 km Rica Queen Maud Land Hertz Population (01.01.05) 4.606.363 Main cities (01.01.03) Oslo 521.886 Bergen 237.430 CLOTHES/EQUIPMENTS/GIFTS Trondheim 154.351 Stavanger 112.405 TO THE NORWEGIAN OLYMPIC TEAM Kristiansand 75.280 Fredrikstad 61.897 Adidas Life expectancy: Men: 76,4 Women: 81,5 Phenix Length of common frontiers: 2.542 km Dale of Norway - Sweden 1.619 km - Finland 727 km Ricco Vero - Russia 196 km Brand Store - Shortest distance north/south 1.752 km Length of the continental coastline 21.465 km Morris - Not incl. Fjords and bays 2.650 km Attello Greatest width of the country 430 km Least width of the country 6,3 km Craft Largest lake: Mjøsa 362 km2 Interplaza Longest river: Glomma 600 km Highest waterfall: Skykkjedalsfossen 300 m Highest mountain: Galdhøpiggen 2.469 m Largest glacier: Jostedalsbreen 487 km2 Longest fjord: Sognefjorden 204 km Prime Minister: Jens Stoltenberg Head of state: H.M. King Harald V and H.M. Queen Sonja Monetary unit: NOK (Krone) 25.01.06: 1 EUR = 8,03 NOK 68139_Innledning 30-01-06 09:33 Side 1 NORWAY’S TOP SPORTS PROGRAMME On a mandate from the Norwegian Olympic Committee (NOK) and Confederation of Sports (NIF) has been given the operative responsibility for all top sports in the country. -

Milano Cortina 2026

MILANO M.T. MILANO CORTINA 2026 CORTINA Candidate City Olympic Winter Games INDEX 1 2 3 4 5 VISION AND GAMES PARALYMPIC SUSTAINABILITY GAMES GAMES CONCEPT EXPERIENCE WINTER GAMES AND LEGACY DELIVERY MILANO VISION AND CORTINA GAMES CONCEPT _2026 VISION AND 1 GAMES CONCEPT The Milano Cortina 2026 ting of the Italian Alps. Having hosted the 1956 Olympic Winter ity. We know that delivering intense sporting moments in inspi- 1 | Olympic Vision Games, Cortina, the Queen of the Dolomites, is an international rational metropolitan and mountainous settings has the power winter sports destination of the highest acclaim, with an excel- to change lives. We want the world to love winter sports like we A partnership inspired by Agenda 2020 lent track record and relationships with national and interna- do, inspired by amazing athletic performances; tional sports federations. A proud host city for the 2021 World The Milano Cortina 2026 Candidature was inspired by the Alpine Ski Championships, it was praised for its sustainable ap- Embrace Sustainability - We want to build on our strong IOC’s Agenda 2020 and presentation of ‘New Norm’ which proach to ensure protection of the sensitive alpine ecosystem. It environmental credentials. We will use the Games to help clearly repositions hosting the Olympic and Paralympic is an interesting example of a multi-cultural, multi-lingual socie- accelerate our work at the forefront of sustainability to help Games as an event that is more sustainable, more flexible ty with clear ambitions for a sustainable future. develop innovative and sustainable solutions to shape lives of and more efficient, both operationally and financially, whilst the future. -

Official Report, III Olympic Winter Games, Lake Placid, 1932

Citius Altius Fortius OFFICIAL REPORT III Olympic Winter Games LAKE PLACID 1932 Issued by III Olympic Winter Games Committee LAKE PLACID, N Y, U S A Compiled by GEORGE M LATTIMER Copyright 1932 III Olympic Winter Games Committee PRINTED IN U S A Contents PAGE Foreword ................................................. 7 Official congratulations.......................................... 8, 9 List of officers and committees...............................11-16 Olympic regulations and protocol and general rules...............23-34 Brief history of Olympic Winter Games.......................35, 36 History of winter sports at Lake Placid........................37-42 How III Olympic Winter Games were awarded to Lake Placid........43-52 Organization following award of Games to Lake Placid............53-72 General organization...................................... 73-78 Finance............................................... 79-92 Publicity ..............................................93-108 Local Arrangements Housing .......................................103-115 Transportation.........................................115 Health and safety................................... 115, 116 Special sections Office lay-out .......................................... 117 Entry forms .......................................117-122 Tickets.......................................... 122-123 Attendance.........................................123, 125 Diplomas, medals, and badges.........................126, 127 International secretary...............................128 -

Overall Achievements of Latvian Luge Athletes 1973 – 2018

Overall achievements of Latvian Luge athletes 1973 – 2018 "LATVIAN LUGE FEDERATION" Grostonas street 6b, Riga, LV-1013, Latvia Tel.:+371 67294779 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Contents OLYMPISCHE WINTERSPIELE Kunstbahn .......................................................................... 3 OLYMPIC WINTER GAMES Artificial Track ........................................................................ 3 WELTMEISTERSCHAFTEN Kunstbahn ............................................................................... 8 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS Artificial Track ......................................................................... 8 WELT – JUNIORENMEISTERSCHAFTEN Kunstbahn ......................................................... 18 WORLD JUNIOR CHAMPIONSHIPS Artificial Track .......................................................... 18 EUROPAMEISTERSCHAFTEN Kunstbahn ......................................................................... 30 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS Artificial Track ................................................................. 30 EUROPA – JUNIORENMEISTERSCHAFTEN Kunstbahn .................................................... 44 EUROPEAN JUNIOR CHAMPIONSHIPS Artificial Track .................................................... 44 WELTCUP Kunstbahn ...................................................................................................... 50 WORLD CUP Artificial Track ............................................................................................ 50 SPRINT WELTCUP Kunstbahn ........................................................................................ -

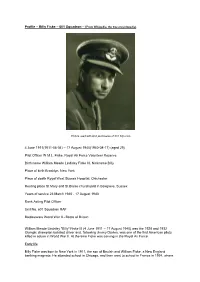

Billy Fiske – 601 Squadron – (From Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia)

Profile – Billy Fiske – 601 Squadron – (From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia) Picture used with kind permission of 601 Sqn.com 4 June 1911(1911-06-04) – 17 August 1940(1940-08-17) (aged 29) Pilot Officer W.M.L. Fiske, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Birth name William Meade Lindsley Fiske III, Nickname Billy Place of birth Brooklyn, New York Place of death Royal West Sussex Hospital, Chichester Resting place St Mary and St Blaise churchyard in Boxgrove, Sussex Years of service 23 March 1940 - 17 August 1940 Rank Acting Pilot Officer Unit No. 601 Squadron RAF Battles/wars World War II - Battle of Britain William Meade Lindsley "Billy" Fiske III (4 June 1911 – 17 August 1940) was the 1928 and 1932 Olympic champion bobsled driver and, following Jimmy Davies, was one of the first American pilots killed in action in World War II. At the time Fiske was serving in the Royal Air Force. Early life Billy Fiske was born in New York in 1911, the son of Beulah and William Fiske, a New England banking magnate. He attended school in Chicago, and then went to school in France in 1924, where he discovered the sport of bobsled at the age of 16. Fiske attended Trinity Hall, Cambridge in 1928 where he studied Economics and History. Fiske then worked at the London office of Dillon, Reed & Co, the New York bankers. On 8 September 1938, Fiske married Rose, Countess of Warwick, in Maidenhead. Bobsled career As driver of the first five-man U.S. Bobsled team to win the Olympics, Fiske became the youngest gold medalist in the sport, aged just 16 years at the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. -

Dovnload *PDF File Witth Complete Information!

LATVIA Republic of Latvia, abbreviated: Latvia Latvian Latvija German Lettland French Lettonie Spanish Letonia Population in 2005 2,306,600 Latvians 58,2%, Russians 29,2%, Belorussians 4,0%, other nationalities 8,6% Official language Latvian – a Baltic language, belongs to the Indo-European language family and uses the Latin alphabet Most common foreign languages English, Russian and German. Capital Riga Politics Latvia is a democratic parliamentary republic President Vaira VIKE–FREIBERGA Prime Minister Aigars KALVITIS Latvia is a member of the European Union since May 2004 History The Republic of Latvia was founded on November 18, 1918. It has been continuously recognised as a state by other countries since 1920 despite occupation by the Soviet Union (1940 – 1941, 1945 – 1991) and Nazi Germany (1941 – 1945). On August 21, 1991 Latvia declared the restoration of its de facto independence. Geography Latvia is one of the three Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). Area 64,589 sq.km or 24,937 sq.miles. Length of Latvia’s Baltic coastline 494 km. Highest point Gaizinkalns, 311,6 m. Longest river within the territory The Gauja, 452 km Climate Moderate climate with an average temperature of +15.8°C in summer and – 4.5°C in winter. Sources http:// www.li.lv Uniforms For the twentieth time Winter Olympic Games in Torino will unite not only athletes but also sport fans and supporters all over the world. During seventeen days of Olympiad sport supporters and enthusiasts in Latvia, too, will attentively follow most exciting moments of fortune or misfortune of athletes. At the Torino 2006 Games, Latvia will be represented by 58 athletes - the biggest delegation in our Olympic history: 23 hockey-players, 8 luge sledders, 10 bobsledders, 2 alpine skiers, 4 cross country skiers, 9 biathletes, 1 skeleton slider and 1 short track skater. -

INSERATE Walliser Bote Donnerstag, 16

AZ 3900 Brig Donnerstag, 16. Februar 2006 Auflage: 26 849 Ex. 166. Jahrgang Nr. 39 Fr. 2.— www.walliserbote.ch Redaktion: Tel. 027 922 99 88 Abonnentendienst: Tel. 027 948 30 50 Mengis Annoncen: Tel. 027 948 30 40 Foto erzielt Die angekündigte Sensation Rekordpreis N e w Y o r k. – (AP) Ein Fo- to von Edward Steichen mit Martina Schild holte Silber in der Abfahrt – Olympiasieg an Michaela Dorfmeister dem Titel «The Pond-Moon- light» ist in New York für 2,928 Millionen Dollar (2,46 Millionen Euro) versteigert worden. Das ist nach Anga- ben des Auktionshauses So- theby’s der höchste Preis, der jemals für eine Fotografie gezahlt wurde. Wer der Käu- fer ist, wurde nicht mitge- teilt. Das Foto wurde 1904 auf Long Island im US-Staat New York aufgenommen und zeigt einen von Bäumen um- gebenen Weiher, in dem sich das Mondlicht spiegelt. Von (wb) Martina Schild sorgte für dem Foto, das etwa 48 Zenti- eine der grössten Schweizer meter auf 40 Zentimeter Überraschungen, die es an misst, gibt es nur drei Abzü- olympischen Skirennen je gab: ge; die anderen beiden befin- Silber in der Abfahrt hinter den sich in Museen. Michaela Dorfmeister Es war eines von 8500 Fotos, Es war so etwas wie eine an- die das New Yorker Metro- gekündigte Sensation. Im Qua- politan Museum of Art ver- lifikationsduell gegen Monika gangenes Jahr aus der Gil- Dumermuth hatte sich die 24- man-Paper-Co.-Sammlung jährige Grindelwaldnerin mit erwarb und von denen am Bestzeit durchgesetzt. Die Kon- Dienstag und Mittwoch kurrenz staunte. Die Frage war knapp 140 bei Sotheby’s ver- bloss: Würden die Nerven auch steigert werden sollten. -

BOBSLEIGH: Getting Off on the Right Foot Whether It’S the Four-Man Event, Or the Two-Man Competition, It All Starts with a Good Start

BOBSLEIGH SCHEDULE » Day 9 » Day 12 » Day 15 » Day 16 Saturday, Feb. 20 Tuesday, Feb. 23 Friday, Feb. 26 Saturday, Feb. 27 Men’s two-man Women’s two-man Men’s four-man Men’s four-man 5-7:40 p.m. 5-7 p.m. 1-3:45 p.m. *1-3:25 p.m. *Indicates medal event » Day 10 » Day 13 Sunday, Feb. 21 Wednesday, Feb. 24 Men’s two-man Women’s two-man *1:30-3:50 p.m. *5-7 p.m. The Whistler Sliding Centre DECONSTRUCTING THE GAMES BOBSLEIGH: Getting off on the right foot Whether it’s the four-man event, or the two-man competition, it all starts with a good start. Or it ends with a bad one. Canwest News Service writer Bob Duff explains: 1.GETTING SET 2.THE START Let’s get started From a standing start,the crew pushes the sled in unison. Explosiveness is key. Speed and strength are key. An Olympic bobsledder must Like runners in starting blocks awaiting the be able to run like the wind,but also be equipped with the gun,the four pushers grab hold of the sled strength to turn a 630-kg sled into a self-propelled rocket. handles and brace themselves for the ride of their lives.It’s why track athletes make such good bobsledders:if they get out 3. FILING IN 4.ON THE MOVE 5.STEADY ON of the gate slowly,the race is already over. The pilot is first to load,grab- Nearing the end of It’s all in the driver’s bing the rope in both hands to the start,loading the hands now.If they steer the sled.He’s followed in sled commences as haven’t reached this by the two pushers,while the the pilot takes the point within at least brakeman continues his run reins.Already,their 1/10th of a second of the from the back of the sled, speed is nearing 40 fastest start — which loading last.