EC74-493 Menswear... Front & Back Interfacing for Jackets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. Review Article DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool Usha Chowdhary* Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Mich- igan, USA *Corresponding author: Usha Chowdhary, Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan, USA. Email: [email protected] Citation: Chowdhary U (2019) Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Received Date: March 5, 2019; Accepted Date: March 20, 2019; Published Date: March 29, 2019 Abstract The study examined breaking strength, elongation and time at break for 100% medium weight knitted wool with in- terfacings and lining. Several ASTM standards were used to measure structural and performance attributes. Fabric strength, elongation, and time taken to rupture for fabric exclusively and with interfacings and lining attached were measured for eight relationships. Hypotheses were tested using T-test analysis. Confidence level was established at 95%. Results revealed that majority of the hypotheses were accepted. Results for fusible and non-fusible interfacings varied. Adding fusible interfacing did not enhance strength in the lengthwise direction. Fusible and non-fusible interfacings did not differ for elongation. It took longer for fabric to break in lengthwise than the crosswise direction. Future research is needed to confirm the findings of this study for various fabrics, seam types, stitch types, fabric construction and fiber contents. -

Aic Paintings Specialty Group Postprints

1991 AIC PAINTINGS SPECIALTY GROUP POSTPRINTS Papers presented at the Nineteenth Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works Albuquerque, New Mexico Saturday, June 8,1991. Compiled by Chris Stavroudis The Post-Prints of the Paintings Specialty Group: 1991 is published by the Paintings Specialty Group (PSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works (AIC). These papers have not been edited and are published as received. Responsibility for the methods and/or materials described herein rests solely with the contributors and these should not be considered official statements of the Paintings Specialty Group or the American Institute for Conservation. The Paintings Specialty Group is an approved division of the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works (AIC) but does not necessarily represent AIC policies or opinions. The Post-Prints of the Paintings Specialty Group: 1991 is distributed to members of the Paintings Specialty Group. Additional copies may be purchased from the American Institute for Conservation of Historical and Artistic Works; 1400 16th Street N.W., Suite 340; Washington, DC 20036. Volume designed on Macintosh using QuarkXPress 3.0 by Lark London Stavroudis. Text printed on Cross Pointe 60 lb. book, an acid-free, recycled paper (50% recycled content, 10% post-consumer waste). Printing and adhesive binding by the Mennonite Publishing House, Scottdale, Pennsylvania. TABLE OF CONTENT S Erastus Salisbury Field, American Folk Painter: 4 His Changing Style And Changing Techniques Michael L. Heslip and James S. Martin The Use of Infra-red Vidicon and Image Digitizing Software in 4 Examining 20th-century Works of Art James Coddington Paintings On Paper: Collaboration Between Paper 11 and Paintings Conservators Daria Keynan and Carol Weingarten Standard Materials for Analysis of Binding Media and 23 GCI Binding Media Library Dusan C. -

Tailoring Series TECHNIQUES for TAILORING UNDERLINING a TAILORED GARMENT—Underlining Is a Second Layer of Fabric. It Is Cut By

tailoring series TECHNIQUES FOR TAILORING UNDERLINING A TAILORED GARMENT—Underlining is a second layer of fabric. It is cut by the garment pattern pieces and staystitched to the wrong side of the corresponding outer sections before any seams are joined. The two layers are then handled as one. As a general guide, most suit jackets and coats look more pro- fessional when underlined. Underlining is especially recommended for lightweight wool materials, loosely woven materials and light- colored materials. For additional information on selecting fabrics for underlining and applying the underlining, see Lining a Shirt 01' Dress HE 72, N. C. Agricultural Extension Service. STAYSTITCHING—Staystitch all outer garment pieces before construction begins. If garment is underlined, stays-titching is done when the two layers of fabric are sewn together. Staystitch 1/3 in. outside seamline (on the seam allowance). Stay- stitch “ with matching cotton thread on all curved *areas that may stretch during construction such as necklines, side seams, shoulder seams, armholes, and side seams of skirt. Use directional stitching always to prevent stretching of fabric and to prevent one layer of fabric from riding. The direction to stitch is indicated by small arrows on the pattern on the seamlines. INTERFACINGS—Select a high quality hair canvas for the front and collar of coats and jackets. The percentage of wool indicates the quality—the higher the wool content of the canvas the better the quality. Since a high percentage of wool makes the hair canvas fairly dark in color, it cannot be used successfully under light-colored fabrics. In these cases use an interfacing lighter in color and lower in wool content. -

Info/How to Examine an Antique Painting.Pdf

How to Examine an Antique Painting by Peter Kostoulakos Before we can talk about the examination process, an overview of how to handle an oil painting is necessary to prevent damage to the work and liability for the appraiser. The checklist below is essential for beginning appraisers to form a methodical approach to examining art in the field without heavy, expensive equipment. Although the information may seem elementary for seasoned appraisers, it can be considered a review with a few tips to organize your observational skills. When inspecting an antique painting, as with any antique, a detailed on the spot, examination should take place. A small checklist covering composition, support, paint layers, varnish, and frame is necessary. Also, a few tools such as a UV lamp, magnifiers, camera, soft brush, cotton swabs, and tape measure are needed. A "behind the scenes" investigation can tell you a great deal about the painting. The name of the artist, title of the painting, canvas maker, date of canvas and stretcher, exhibitions and former owners are some of the things that may be revealed upon close examination. Document your examination with notes and plenty of photographs. Handling Art Older paintings should be thought of as delicate babies. We need to think about the consequences before we pick one up. To prevent acidic oil from our skin to be transferred to paintings and frames, we must cover our hands with gloves. Museum workers have told me that they feel insecure using white, cotton gloves because their grip becomes slippery. I tried the ceremonial gloves used in the military to grip rifles while performing. -

Ajsl ,QJI 8Ji)9

ajsL ,QJI 8jI)9 MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS L",uitom cz4 /ppaLf ('"oduaDon P'"zuocz1 Volume 2 TAILORING //, INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT aLSioJ 8jsto!*14I 3toj3JI J54o 4sjflko MINSTRY OF SOCIAL AFFAIRS cwitom c92/I/2a'LEf ?'oduation 57P/D 0 E15 ('uvzicul'um JoL CSPP nstzucto~ Volume 2 TAILORING g~jji~JI 6&= z#jJEi l tl / INTEGRATED SOCIAL SERVICES PROJECT wotsoi stoim 1oj3jw jsi.Lo 6suJf PREFACE The material which follows is .J l.a ,,h &*.aJIL& . part of a five volume series assem bled by the faculty and students of . 3aJ e~- t.l. -, r'- ,tY.. the University of North Carolina at L_:J q L--, X4 0-j VO Greensboro, Department of Clothing and Textiles, CAPP Summer Program. The CAPP, Custom Appar,1 Production LFJI L,4.," ,'"i u .U. J l Process, Program was initiated in Egypt as a part of the Integrated Social Services Project, Dr. Salah L-,S l k e. L C-j,,. El Din El Hommossani, Project Direc- - L0 C...J L'j tor, and under the sponsorship of 4 " r th Egyptian Ministry of Social !.Zl ij1.,1,,.B= r,L..,J1....J Affairs and the U.S. Agency for - .Jt , . -t. International Development. These materials were designed for use in . J L.Jt CSziJtAJI #&h* - L*J training CAPP related instructors t .L-- -- J and supervisors for the various programs of the Ministry of Social ._ . , .. .. Affairs and to provide such person- L , *i. l I-JL-j 6 h nel with a systematica,'ly organized und detailed curriculum plan which JL61tJ J..i..- J" could be verbally transferred to O| ->. -

Tailoring and Dressm King 5 LINING A. SKIRT Or DRESS Today's Fashions

tailoring and dressm king 5 LINING a. SKIRT or DRESS Today’s fashions and fabrics often call for linings. This raises questions among the home seamstresses regarding types of lining and how to attach these to the garment. Lining serves many purposes. It: 0 gives a professional 100k and adds quality 0 adds body and/or opacity to lightweight or thin fabric 0 gives roundness to structural lines where needed 0 prevents sagging, stretch or “sitting " out” in straight skirts (helps to preserve shape of garment) ' 0 gives longer service to the garment 0 helps to eliminate wrinkles A distinCtion should be made among four sometimes confusing terms: 1. Lining refers to a material that partially or entirely covers the inside of a garment. It is assembled separately as though it were a second garment. It finishes the wrong side of the garment as well as serving the purposes listed C above. For better fit and more strength it should be cut on the same grain as the outer fabric. 2. Underlining is a material which is cut in the shape of the garment pieces. The underlining sections are staystitched to- the corresponding outer fabric sections before any seams are joined. This is especially good for loosely woven or thin fabrics. This treatment is usually called “double fabric con- struction.” It is also called backing or underlay. 3. Interlining ,is usually thought of as giving warmth to a coat as well as giving some shape. The interlining is cut' to match the garment pieces and is placed between the lining and the outer fabric. -

Simplified Sewing: Hems

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange SDSU Extension Fact Sheets SDSU Extension 1964 Simplified Sewing: Hems Cooperative Extension South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_fact Recommended Citation South Dakota State University, Cooperative Extension, "Simplified Sewing: Hems" (1964). SDSU Extension Fact Sheets. 865. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/extension_fact/865 This Fact Sheet is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Extension at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in SDSU Extension Fact Sheets by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .. ... -~--- - --v · . --,-.-.- , -. ·. ..•, .. ·'··· .••,.,. - .t:\. --(. ......., • ... ·\•i• ....,.,•-•1•,··...- .,.. "\' ·,- • • • -:\. -: ·):.~\:,..,:}:,:.·,:,..,:;:,:.~:,-:-,:.0:.- ·,~\:,.!;;;; ··:,:.\!.t:,-;..:,t;.,:,:,:.i:1:,:.'.:.•; .-·F_:,~::::_:.~:~~~~~;.:::z~:;:'.·---~-~;:~~L ::·.1~~~~1::.:;.:_;~~: File Copy FS244 THE l-lE~I of your dress can have the "professional - Wearer should stand in a natural position with look" or the "homemade look." In general, the best arms at sides and weight on both feet. hem is the least conspicuous, and every step in making a hem is planned with this in mind There are several methods of marking a hem. You may use any one of these: The professional touch is recognize-cl by the follow- ing characteristics: Various types of chalk markers or pin markers - Inconspicuous from the right side Yardstick - Even distance from the floor Tailor's square. - Wide enough for good proportion and to gi\.re With some of these you can mark enough weight to hang well your own hem; others require a - Even in width help«. -

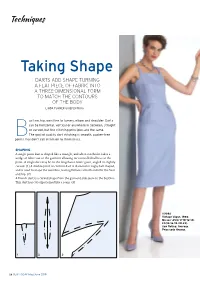

Taking Shape DARTS ADD SHAPE TURNING a FLAT PIECE of FABRIC INTO a THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM to MATCH the CONTOURS of the BODY LINDA TURNER GRIEPENTROG

Techniques Taking Shape DARTS ADD SHAPE TURNING A FLAT PIECE OF FABRIC INTO A THREE-DIMENSIONAL FORM TO MATCH THE CONTOURS OF THE BODY LINDA TURNER GRIEPENTROG ustline, hip, waistline to tummy, elbow and shoulder. Darts can be horizontal, vertical or anywhere in between, straight or curved, but the stitching principles are the same. BThe goal of quality dart stitching is smooth, pucker-free points that don’t call attention to themselves. SHAPING A single-point dart is shaped like a triangle, and when stitched it takes a wedge of fabric out of the garment allowing for controlled fullness at the point. A single dart may be on the lengthwise fabric grain, angled or slightly curved. (1) A double-point or contour dart is diamond or rugby ball shaped, and is used to shape the waistline, leaving fullness at both ends for the bust and hip. (2) A French dart is a curved shape from the garment side seam to the bustline. This dart has cut edges joined like a seam. (3) V9082 Vintage Vogue, 1960. Misses’ A5(6-8-10-12-14) E5(14-16-18-20-22). Sew Rating: Average. Price code Orange. Illustrations: Theresa O’Connell Theresa Illustrations: 1 2 3 26 SEW TODAY May/June 2019 MARKING to anchor the stitches. Stitch (7) and stitch toward the point, Darts are indicated on the along the line, removing the A third technique for dart then repeat for the other pattern tissue by either solid pins as you get to them. Taper point, slightly overlapping or dashed lines and a dot the stitching to the point the beginning stitching lines at the point. -

VTE Framework: Fashion Technology

Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education Vocational Technical Education Framework Business & Consumer Services Occupational Cluster Fashion Technology (VFASH) CIP Code 500407 June 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 781-338-3910 www.doe.mass.edu/cte/ This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D. Commissioner Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Ms. Maura Banta, Chair, Melrose Ms. Harneen Chernow, Vice Chair, Jamaica Plain Mr. Daniel Brogan, Chair, Student Advisory Council, Dennis Dr. Vanessa Calderón-Rosado, Milton Ms. Karen Daniels, Milton Ms. Ruth Kaplan, Brookline Dr. Matthew Malone, Secretary of Education, Roslindale Mr. James O’S., Morton, Springfield Dr. Pendred E. Noyce, Weston Mr. David Roach, Sutton Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D., Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA 02148-4906. Phone: 781-338-6105. © 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes. -

Scissors [680

Sales office: +39 015 40 1935 - [email protected] www.tessilmarket.it Scissors TESSILMARKET srl CODE TBFL0110 TBFL0113 DESCRIPTION SEWING SCISSORS SEWING SCISSORS Blades = nickel plated steel with steel handles Blades = nickel plated steel with steel handles FEATURES Lenght = tot. 10 cm. (4”) Lenght = tot. 13 cm. (5”) Blades = 3,5 cm. (1,35”) Blades = 5 cm. (2”) WEIGHT 30 gr. 42 gr. CODE TBFL0115 TBFL0213 DESCRIPTION SEWING SCISSORS DRAPER SCISSORS Blades = nickel plated steel with steel handles Blades = nickel plated steel with pla- stic handles FEATURES Lenght = tot. 15 cm. (6”) Lenght = tot. 13 cm. (5”) Blades = 6 cm. (2,5”) Blades = 5 cm. (2”) WEIGHT 60 gr. 45 gr. CODE TBFL0218 TBFL0315 DESCRIPTION DRAPER SCISSORS DRAPER SCISSORS Blades = nickel plated steel with plastic Blades = inox plated steel ASI420 with handles nylon handles FEATURES Lenght = tot. 18 cm. (7”) Lenght = tot. 15 cm. (6”) Blades = 7,5 cm. (3”) Blades = 6,5 cm. (2,5”) WEIGHT 75 gr. 45 gr. Sales office: +39 015 40 1935 - [email protected] www.tessilmarket.it Scissors TESSILMARKET srl CODE TBFM0110 TBFM0113 DRAPER SCISSORS DESCRIPTION DRAPER SCISSORS Blades = with rounded tips in nickel plated steel with plastic Blades = with rounded tips in nickel plated steel handles and steel handles FEATURES Lenght = tot. 10 cm. (4”) Lenght = tot. 13 cm. (5”) Blades = 4 cm. (1,6”) Blades = 5 cm. (2”) WEIGHT 25 gr. 42 gr. CODE TBFM0216 TBFR0110 DESCRIPTION DRAPER SCISSORS EMBROIDERY SCISSORS Blades = with rounded tips in nickel plated steel with plastic Blades = sharp tips in nickel plated steel handles and steel handles FEATURES Lenght = tot. -

Sew Wow Advanced Clothing Member's Guide

SEW WOW #32009 Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements This guide belongs to:_________________________________ Year:________ SEW WOW Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements Contents Project Objectives Project Objectives............................................2 • Learn to enjoy and appreciate the process of clothing construction. Requirements ...................................................2 • Acquire the advanced skills needed to create Focus Areas Summary .....................................3 a garment, outfit, and/or accessories. General Resources ...........................................3 • Develop confidence through successfully Focus Area A: Active/Sportswear....................4 completing the project. Focus Area B: Outdoor Wear...........................6 • Share what you have learned with others. Focus Area C: Western Wear ...........................8 Focus Area D: Formal Wear ..........................10 Requirements Focus Area E: Embellished Apparel..............12 1. Select one project focus area that includes the clothing item(s), fabric, and construction Focus Area F: Tailored Apparel.....................14 skills you want to master. A summary of Focus Area G: Pattern Your Own..................16 focus areas is on page 3. General Advanced Activities .........................18 2. Set at least three goals to achieve in this project year. Project Summary ...........................................19 Part A: General Advanced Activity ..........19 3. Do one of the “General Advanced -

80739083.Pdf

3-~"'81 8-1355 ~.(O~ All About ... • Pattern Selection • Fabric Selection • Contemporary Techniques • Fusible Interfacings • Finishing Tips CONTENTS Page Pattern Selection. ............................................... .. 3 Fabric Selection ................................................ .. 3 Notions. ....................................................... .. 3 Pressing Points ................................................. .. 4 Inner Fabrics. .................................................. .. 4 Underlining. ................................................. .. 4 Interfacing. .................................................. .. 4 Lining. ..................................................... .. 5 Preparation ............................................ .. 5 Fabric. ...................................................... .. 5 Pattern Fit. .................................................. .. 5 Cutting and Marking. ......................................... .. 5 Comparison of Custom and Contemporary Tailoring Techniques. ...... .. 5 Front and Back Interfacing. ...................................... .. 5 Fusible Method-Front. ...................................... .. 5 onfusible Method-Back Reinforcement. ....................... .. 6 One-Piece Method. ........................................ .. 6 Two-Piece Method ......................................... .. 6 Applying Back Reinforcement .................................. .. 7 Lapel and Roll Line ............................................. .. 7 Marking the Roll Line , 8 Taping the