Aic Paintings Specialty Group Postprints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U

International Journal of Textile Science and Engineering Chowdhary U. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. Review Article DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool Usha Chowdhary* Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Mich- igan, USA *Corresponding author: Usha Chowdhary, Department of Human Environmental Studies Fashion Merchandising and Design, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan, USA. Email: [email protected] Citation: Chowdhary U (2019) Impact of Interfacings and Lining on Breaking Strength, Elongation and Duration of the Test for Knitted Wool. Int J Text Sci Eng 3: 125. DOI: 10.29011/IJTSE-125/100025 Received Date: March 5, 2019; Accepted Date: March 20, 2019; Published Date: March 29, 2019 Abstract The study examined breaking strength, elongation and time at break for 100% medium weight knitted wool with in- terfacings and lining. Several ASTM standards were used to measure structural and performance attributes. Fabric strength, elongation, and time taken to rupture for fabric exclusively and with interfacings and lining attached were measured for eight relationships. Hypotheses were tested using T-test analysis. Confidence level was established at 95%. Results revealed that majority of the hypotheses were accepted. Results for fusible and non-fusible interfacings varied. Adding fusible interfacing did not enhance strength in the lengthwise direction. Fusible and non-fusible interfacings did not differ for elongation. It took longer for fabric to break in lengthwise than the crosswise direction. Future research is needed to confirm the findings of this study for various fabrics, seam types, stitch types, fabric construction and fiber contents. -

Info/How to Examine an Antique Painting.Pdf

How to Examine an Antique Painting by Peter Kostoulakos Before we can talk about the examination process, an overview of how to handle an oil painting is necessary to prevent damage to the work and liability for the appraiser. The checklist below is essential for beginning appraisers to form a methodical approach to examining art in the field without heavy, expensive equipment. Although the information may seem elementary for seasoned appraisers, it can be considered a review with a few tips to organize your observational skills. When inspecting an antique painting, as with any antique, a detailed on the spot, examination should take place. A small checklist covering composition, support, paint layers, varnish, and frame is necessary. Also, a few tools such as a UV lamp, magnifiers, camera, soft brush, cotton swabs, and tape measure are needed. A "behind the scenes" investigation can tell you a great deal about the painting. The name of the artist, title of the painting, canvas maker, date of canvas and stretcher, exhibitions and former owners are some of the things that may be revealed upon close examination. Document your examination with notes and plenty of photographs. Handling Art Older paintings should be thought of as delicate babies. We need to think about the consequences before we pick one up. To prevent acidic oil from our skin to be transferred to paintings and frames, we must cover our hands with gloves. Museum workers have told me that they feel insecure using white, cotton gloves because their grip becomes slippery. I tried the ceremonial gloves used in the military to grip rifles while performing. -

Tailoring and Dressm King 5 LINING A. SKIRT Or DRESS Today's Fashions

tailoring and dressm king 5 LINING a. SKIRT or DRESS Today’s fashions and fabrics often call for linings. This raises questions among the home seamstresses regarding types of lining and how to attach these to the garment. Lining serves many purposes. It: 0 gives a professional 100k and adds quality 0 adds body and/or opacity to lightweight or thin fabric 0 gives roundness to structural lines where needed 0 prevents sagging, stretch or “sitting " out” in straight skirts (helps to preserve shape of garment) ' 0 gives longer service to the garment 0 helps to eliminate wrinkles A distinCtion should be made among four sometimes confusing terms: 1. Lining refers to a material that partially or entirely covers the inside of a garment. It is assembled separately as though it were a second garment. It finishes the wrong side of the garment as well as serving the purposes listed C above. For better fit and more strength it should be cut on the same grain as the outer fabric. 2. Underlining is a material which is cut in the shape of the garment pieces. The underlining sections are staystitched to- the corresponding outer fabric sections before any seams are joined. This is especially good for loosely woven or thin fabrics. This treatment is usually called “double fabric con- struction.” It is also called backing or underlay. 3. Interlining ,is usually thought of as giving warmth to a coat as well as giving some shape. The interlining is cut' to match the garment pieces and is placed between the lining and the outer fabric. -

VTE Framework: Fashion Technology

Massachusetts Department of Elementary & Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education Vocational Technical Education Framework Business & Consumer Services Occupational Cluster Fashion Technology (VFASH) CIP Code 500407 June 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Office for Career/Vocational Technical Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 781-338-3910 www.doe.mass.edu/cte/ This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D. Commissioner Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Ms. Maura Banta, Chair, Melrose Ms. Harneen Chernow, Vice Chair, Jamaica Plain Mr. Daniel Brogan, Chair, Student Advisory Council, Dennis Dr. Vanessa Calderón-Rosado, Milton Ms. Karen Daniels, Milton Ms. Ruth Kaplan, Brookline Dr. Matthew Malone, Secretary of Education, Roslindale Mr. James O’S., Morton, Springfield Dr. Pendred E. Noyce, Weston Mr. David Roach, Sutton Mitchell D. Chester, Ed.D., Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA 02148-4906. Phone: 781-338-6105. © 2014 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes. -

Sew Wow Advanced Clothing Member's Guide

SEW WOW #32009 Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements This guide belongs to:_________________________________ Year:________ SEW WOW Advanced Clothing Member’s Guide and Project Requirements Contents Project Objectives Project Objectives............................................2 • Learn to enjoy and appreciate the process of clothing construction. Requirements ...................................................2 • Acquire the advanced skills needed to create Focus Areas Summary .....................................3 a garment, outfit, and/or accessories. General Resources ...........................................3 • Develop confidence through successfully Focus Area A: Active/Sportswear....................4 completing the project. Focus Area B: Outdoor Wear...........................6 • Share what you have learned with others. Focus Area C: Western Wear ...........................8 Focus Area D: Formal Wear ..........................10 Requirements Focus Area E: Embellished Apparel..............12 1. Select one project focus area that includes the clothing item(s), fabric, and construction Focus Area F: Tailored Apparel.....................14 skills you want to master. A summary of Focus Area G: Pattern Your Own..................16 focus areas is on page 3. General Advanced Activities .........................18 2. Set at least three goals to achieve in this project year. Project Summary ...........................................19 Part A: General Advanced Activity ..........19 3. Do one of the “General Advanced -

80739083.Pdf

3-~"'81 8-1355 ~.(O~ All About ... • Pattern Selection • Fabric Selection • Contemporary Techniques • Fusible Interfacings • Finishing Tips CONTENTS Page Pattern Selection. ............................................... .. 3 Fabric Selection ................................................ .. 3 Notions. ....................................................... .. 3 Pressing Points ................................................. .. 4 Inner Fabrics. .................................................. .. 4 Underlining. ................................................. .. 4 Interfacing. .................................................. .. 4 Lining. ..................................................... .. 5 Preparation ............................................ .. 5 Fabric. ...................................................... .. 5 Pattern Fit. .................................................. .. 5 Cutting and Marking. ......................................... .. 5 Comparison of Custom and Contemporary Tailoring Techniques. ...... .. 5 Front and Back Interfacing. ...................................... .. 5 Fusible Method-Front. ...................................... .. 5 onfusible Method-Back Reinforcement. ....................... .. 6 One-Piece Method. ........................................ .. 6 Two-Piece Method ......................................... .. 6 Applying Back Reinforcement .................................. .. 7 Lapel and Roll Line ............................................. .. 7 Marking the Roll Line , 8 Taping the -

Lining Techniques... Made Easy

CT-MMB.004 Lining Techniques Jacket and Coat Linings Made Easy A garment lining is generally referred to and treated as a “supportive” fabric. As a rule, a lining eliminates the need for time-consuming seam finishes while lengthening the life and durability of the fashion garment. According to Kathleen Spike, noted clothing writer, “Nothing places a garment in the ‘custom’ or ‘couture’ category as distinctly as a professionally applied lining.” 1 Lining – a separate, but attached inner layer of fabric construction which conceals or covers the inside garment construction. STANDARDS OF A WELL-MADE/APPLIED GARMENT LINING A suitable lining fabric: Is compatible with garment fabric in terms of care and fiber content. It can be cleaned in the same manner as the garment. Can be either woven or knit fabric as long as it is compatible with the garment fashion fabric. Permits and accommodates the necessary “give” and recovery needed for body movement. Is firm, yet not bulky; colorfast to perspiration and body oils; absorbent or “breathable.” Is opaque so as not to see the inside construction of the garment. Matches or coordinates with the garment fashion fabric. Has a smooth surface texture to permit the garment to be taken on and off the body with ease. Weight is the same or somewhat lighter and softer than the fashion fabric so as not to dominate the fashion garment. Is preshrunk (pre-washed or dry-cleaned) prior to cutting. The completed lining: Is cut sufficiently larger than the fashion garment to provide length and width fitting ease (generally at center back, armhole, hem edge, elbow, sleeve hem, shoulder). -

Product Portfolio

Product portfolio 2021 1 Contents About 3 Stickers 31 Photo gifts 62 Clothing 98 Mission 4 Kiss-cut stickers 32 Acrylic prisms 63 Unisex Solutions 5 Clear stickers 33 Photo tiles 64 Unisex t-shirts 99 Services 6 Magnets 65 Unisex hoodies 109 Stationery 34 Jigsaw puzzles 66 Unisex sweatshirts 115 Personalised football cards 67 Unisex jackets 118 Prints 7 Fine art postcards 35 Gallery boards 68 Fine art papers 8 Fine art greetings cards 36 Menswear Square prints 69 Photographic papers 13 Classic postcards 37 Men’s t-shirts 119 Wooden picture stands 70 Mounted prints 15 Classic greetings cards 38 Men’s hoodies 120 Art print with hanger 16 Journals 39 Womenswear Poster hangers 17 Notebooks 40 Home & living 71 Women’s t-shirts 121 Wrapping paper 41 Faux suede & linen cushions 72 Women’s hoodies 127 Framed Prints 18 Canvas cushions 73 Classic frame 19 Device cases 42 Curtains 74 Kidswear Box frame 20 Snap case 43 Wall tapestries 75 Bodysuits 128 Spacer frame 21 Tough case 44 Pillow cases 76 Kid’s t-shirts 130 Surface frame 22 Eco case 45 Shower curtains 77 Kid’s hoodies 134 Gloss frame 23 Clear phone case 46 Bath mats 78 Kid’s sweatshirts 135 Swoop frame 24 Flexi phone case 47 Woven blankets 79 Kid’s jackets 136 Instagram frame 25 Folio wallet case 48 Premium fleece blankets 80 Backloader frame 26 iPad case 49 Pet beds 81 Accessories 137 Laptop sleeves 50 Dog bandanas 82 Canvas tote bags 138 Apple watch bands 51 Photo mugs 83 Canvases 27 Polyester tote bags 139 Coloured photo mugs 84 Stretched canvas 28 Shopping bags 140 Photo books 52 Latte -

Textiles and Apparel

CHAPTER THREE TEXTILES AND APPAREL ARTICLE 3.1: BILATERAL EMERGENCY ACTIONS 1. If, as a result of the reduction or elimination of a duty under this Agreement, a textile or apparel good benefiting from preferential tariff treatment under this Agreement is being imported into the territory of a Party in such increased quantities, in absolute terms or relative to the domestic market for that good, and under such conditions as to cause serious damage, or actual threat thereof, to a domestic industry producing a like or directly competitive good, the importing Party may, to the extent and for such time as may be necessary to prevent or remedy such damage and to facilitate adjustment, take emergency action, consisting of an increase in the rate of duty on the good to a level not to exceed the lesser of: (a) the most-favored-nation (MFN) applied rate of duty in effect at the time the action is taken; and (b) the MFN applied rate of duty in effect on the date of entry into force of this Agreement. 2. In determining serious damage, or actual threat thereof, the importing Party: (a) shall examine the effect of increased imports of the good from the exporting Party on the particular industry, as reflected in changes in such relevant economic variables as output, productivity, utilization of capacity, inventories, market share, exports, wages, employment, domestic prices, profits, and investment, none of which is necessarily decisive; and (b) shall not consider changes in technology or consumer preference as factors supporting a determination of serious damage or actual threat thereof. -

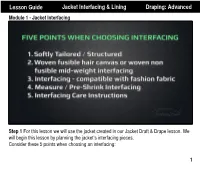

Lesson Guide Jacket Interfacing & Lining Draping: Advanced

Lesson Guide Jacket Interfacing & Lining Draping: Advanced Module 1 - Jacket Interfacing Step 1 For this lesson we will use the jacket created in our Jacket Draft & Drape lesson. We will begin this lesson by planning the jacket’s interfacing pieces. Consider these 5 points when choosing an interfacing: 1 Module 1 - Jacket Interfacing Step 1 Softly Tailored/Structured Decide on the overall look of your jacket. You may wish to create a softly tailored jacket or a more structured jacket. Here we will plan for a softly tailored jacket. 2 Module 1 - Jacket Interfacing Step 2 Woven fusible hair canvas or woven non-fusible mid-weight interfacing. Select the interfacing that best suits the look and the type of fashion fabric that you have chosen. For example, if you are going for a tailored, more structured look you may wish to choose a woven fusible hair canvas. If you are going for a softer look then you might choose a woven non-fusible mid-weight interfacing. 3 Module 1 - Jacket Interfacing Step 3 Interfacing - compatible with fashion fabric Always test various types of interfacing before you make your final selection, to be sure that the final choice is compatible with your choice of fashion fabric. You wouldn’t choose an interfacing that is heavier than your fashion fabric since it might be too overpowering for the overall look of the jacket. 4 Module 1 - Jacket Interfacing Step 4 Measure/Pre-Shrink Interfacing Once you have chosen the appropriate interfacing for your jacket design, whether it be a woven, non-woven or stretch or whether it is fusible or non-fusible, you must test it for shrink- age. -

University International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Embellishments: Exploring Dress in Detail

Embellishments: Exploring Dress in Detail Madeleine Byrne Autumn Quarter 2018 Thesis submitted in completion of Honors Senior Capstone requirements for the DePaul University Honors Program Advisor: Deanna Aliosius, Head of Costume Technology, The Theatre School Faculty Reader: Cheryl Bachand, History of Art and Architecture Abstract: This exhibit and supporting written materials were created to explore historic costume in detail through a variety of techniques and contexts. Using a methods and materials based framework, this exhibit examines three objects and their construction. The supporting framework and theory behind this exhibit has been established by identifying the ways that fashion exhibits in museums have evolved over the 20th and 21st centuries, featuring case study examples from the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Chicago History Museum. This exhibit serves as an example of how fashion might be displayed in museums in the future to better serve its visitors. Table of Contents 1. Theory and Framework Paper 2. Exhibition Catalogue 3. Exhibit Text Deconstructing Fashion in Museums: Theory and Framework Fashion in museums is more present than ever, drawing crowds and perhaps even reinvigorating institutions in need of visitorship. However, despite the commercial success of fashion exhibits that center designers and aesthetics, fashion in the museum setting has greater potential to educate than the current model of blockbuster fashion exhibits allows. Clothing construction methods and materials have much to teach us about fashion objects beyond aesthetic appreciation. Museums must ask what the public stands to gain from exhibits of dress and fashion. Exhibits rooted in scholarship and research centering around materials, construction, and design approach have the potential for greater education and impact than those that frame fashion as pure artistic expression.