Orphan Asylum Building 5120 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law School Announcements 1965-1966 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 9-30-1965 Law School Announcements 1965-1966 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1965-1966" (1965). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 89. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/89 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements 1965-1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL Inquiries should be addressed as follows: Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and finan cial aid: For the J.D. Program: DEAN OF STUDENTS The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2406 For the Graduate Programs: ASSISTANT DEAN (GRADUATE STUDIES) The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2410 Housingfor Single Students: OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3149 Housingfor Married Students: OFFICE OF MARRIED STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 824 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone 752-3644 Payment of Fees and Deposits: THE BURSAR The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3146 The University of Chicago Founded by John D. -

The Chicago City Manual, and Verified by John W

CHICAGO cnT MANUAL 1913 CHICAGO BUREAU OF STATISTICS AND MUNICIPAL UBRARY ! [HJ—MUXt mfHi»rHB^' iimiwmimiimmimaamHmiiamatmasaaaa THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY I is re- The person charging this material or before the sponsible for its return on Latest Date stamped below. underlining of books Theft, mutilation, and disciplinary action and may are reasons for from the University. result in dismissal University of Illinois Library L161-O-1096 OFFICIAL CITY HALL DIRECTORY Location of the Several City Departments, Bureaus and Offices in the New City Hall FIRST FLOOR The Water Department The Fire Department Superintendent, Bureau of Water The Fire Marshal Assessor, Bureau of Water Hearing Room, Board of Local Improve^ Meter Division, Bureau of Water ments Shut-Off Division, Bureau of Water Chief Clerk, Bureau of Water Department of the City Clerk Office of the City Clerk Office of the Cashier of Department Cashier, Bureau of Water Office of the Chief Clerk to the City Clerk Water Inspector, Bureau of Water Department of the City Collector Permits, Bureau of Water Office of the City Collector Plats, Bureau of Water Office of the Deputy City Collector The Chief Clerk, Assistants and Clerical Force The Saloon Licensing Division SECOND FLOOR The Legislative Department The Board's Law Department The City Council Chamber Board Members' Assembly Room The City Council Committee Rooms The Rotunda Department of the City Treasurer Office of the City Treasurer The Chief Clerk and Assistants The Assistant City Treasurer The Cashier and Pay Roll Clerks -

The Street Railway Journal

b THE Street Railway Journal. • INDEX TO VOLUME XXII. July to December, 1903. McGraw Publishing Co., 114 Liberty Street, New York. 80953 INDEX TO VOLUME XXII. (Abbreviations ' Illustrated, c Correspondence.) A Offic'ers. £rid 'EJeciitiv'e Commitee <..!.'*... *284 Brakes, Air: in Detroit 929, 1034 .. 541 Discussion at Williamsport 811 cSa~ratoga "Convention, Excursion's' r Acceleration: on High-Speed Railways — Exhibitors, .. .404/ *542 New Christensen Sales Agents 46 — v { [Armstrong] 27 S- c — Proceedings? c" I . c cx-l--- i 448,486 Storage, St. Louis 1073 *122 t Test .'.« c ComnseEtc or..'..: L',., r i 409, 4(U Electric (Price, Darling) *587 65 Union Traction Company, Indiana.... ' *981 < Programme ,'.£1.2, '239 —Emergency, Motors as [Gough] r c also Speeds.) c (See e .<. — *18 . < Track, e c Cq.fiyiF.ents on v .c'. t'. c 279 —Emergency used in San Francisco. Accident: Boston & Worcester Railway In- c S'dggosf'ions .<\fe . .. c ." 609 Momentum 399 vestigation 215 Vice-President's 'Address .'»(-..« 449 Pneumatic Slipper (Estler Brothers) . .*173, 24a Brooklyn Elevated 958 Ammeter, Graphical Recording *808 ——Test of the Steiner Distance 395 Responsibility of Barents... 220 to Children, Anniston, Ala., Convertible Cars for *269 Braking: Emergency Stops 905, 1016 Claims, from Burning Trolley Wire, Appleyard Syndicate: Double-Track Curves [Johnson] c807, cl016 Kansas City 44 for Single-Track Roads M88 [Richards] c951 Department Methods in Brooklyn System of Interurban Railways *146 Bridgeport Strike 109, 220 ; *654 [Folds] Armatures (see Motors, Electric). Brighton, England, Trucks at 1004 Maintenance and Champerty in Personal Atlanta, Ga., Semi-Convertible Cars *923 Brillium as Fijel 900 Injury Cases [Brennan] 525 Atlantic City, Destructive Hurricane in *699 British Institution of Civil Engineers, Meet- Open-Car Dangers 1044 & Suburban Railway, Cars for 861 ing of 43 Paris Underground, Details of *TT2 Auburn & Syracuse Electric Railway *636 British Westinghouse Company, Trafford Physical Examination from the Physi- Auckland, N. -

Pullman Company Archives

PULLMAN COMPANY ARCHIVES THE NEWBERRY LIBRARY Guide to the Pullman Company Archives by Martha T. Briggs and Cynthia H. Peters Funded in Part by a Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities Chicago The Newberry Library 1995 ISBN 0-911028-55-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................. v - xii ... Access Statement ............................................ xiii Record Group Structure ..................................... xiv-xx Record Group No . 01 President .............................................. 1 - 42 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the President ...................... 2 - 34 Subgroup No . 02 Office of the Vice President .................. 35 - 39 Subgroup No . 03 Personal Papers ......................... 40 - 42 Record Group No . 02 Secretary and Treasurer ........................................ 43 - 153 Subgroup No . 01 Office of the Secretary and Treasurer ............ 44 - 151 Subgroup No . 02 Personal Papers ........................... 152 - 153 Record Group No . 03 Office of Finance and Accounts .................................. 155 - 197 Subgroup No . 01 Vice President and Comptroller . 156 - 158 Subgroup No. 02 General Auditor ............................ 159 - 191 Subgroup No . 03 Auditor of Disbursements ........................ 192 Subgroup No . 04 Auditor of Receipts ......................... 193 - 197 Record Group No . 04 Law Department ........................................ 199 - 237 Subgroup No . 01 General Counsel .......................... 200 - 225 Subgroup No . 02 -

2021 Historical Calendar Cta 2021 January

cta 2021 Historical Calendar cta 2021 January Built in 1936 by the St. Louis Car Company, Chicago Surface Lines trolley bus #184 heads eastbound via Diversey to Western. Trolley bus service was first introduced in Chicago on the #76 Diversey route in 1930. Other trolley bus routes were soon added, some as extensions of existing streetcar lines and later as conversions of streetcar lines to trolley bus service. Trolley bus extensions to existing streetcar lines were an economical way to serve new neighborhoods that were established in outlying parts of the city. Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat ABCDEFG: December 2020 February 2021 B C CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Group Days Off 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 t Alternate day off if 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 you work on this day 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 l Central offices closed 27 28 29 30 31 28 1 New Year’s Day 2 C D E F G A B 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 B C D E F G A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 A B C D E F G Martin Luther King, 17 18 Jr. Day 19 20 21 22 23 G A B C D E F 24 F 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 cta 2021 February Car #1643 was an example of Chicago’s first electric streetcars. -

The Street Railway Journal

Vul. VIII. MEW YORK $ CHICAGO, MARCH Mo. 3. Cincinnati Street Railways. page presents a very good idea of the exterior of the station. Fig. 2 on the following page is a view of Our readers are already familiar in a general way the interior of the engine and generator room, while with the transit facilities of this progressive city. All the Fig. 3 shows to the reader the appearance of the boiler leading systems of traction are employed, including elec- room. tric traction by the single and double trolley, with motors The engine room of the power station is 200 x 60 ft.; boiler room 200x40 ft. The steam equipment consists of three 1,000 h. p. Babcock tfc Wilcox boilers and four en- gines. Three of the engines are of the Corliss type, man- ufactured by Lane & Bodley, of Cincinnati, two of them have 28 x 60 ins. cylinders and one 24x60 ins. The fourth is a 100 h. p. engine manufactured by the Buckeye Engine Co., Salem, O. The present electric equipment consists of sixteen 80 h. p. T.-H. generators, of which thirteen are in daily service, to operate the three lines, known as the East End, Norwood and Avondale. The fly- wheels are twenty-two feet in diameter, with fifty inch faces, and the three belts, furnished by the Bradford Belting J Co. of Cincinnati, O., are forty-eight inches wide, and lead to six foot receiving pulleys. This power house was the scene of the recent accident when one of the heavy fly- FiG. I —EXTERIOR OF HUNT STREET STATION— CINCINNATI STREET RAILWAY CO. -

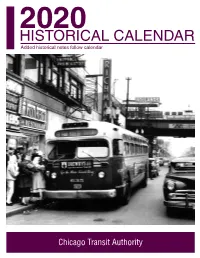

HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added Historical Notes Follow Calendar

2020 HISTORICAL CALENDAR Added historical notes follow calendar Chicago Transit Authority JANUARY 2020 After a snow in December 1951, CTA streetcar #4231 is making its way down Halsted to its terminus at 79th Street. Built in 1948 by the Pullman Company in Chicago, car #4231 was part of a fleet of 600 Presidents Conference Committee (PCC) cars ordered by Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) just before its incorporation into the Chicago Transit Authority. At 48 feet, these were the longest streetcars used in any city. Their comfortable riding experience, along with their characteristic humming sound and color scheme, earned them being nicknamed “Green Hornets” after a well-known radio show of the time. These cars operated on Chicago streets until the end of streetcar service, June 21, 1958. Car #4391, the sole survivor, is preserved at the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, IL. SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT ABCDEFG: December 2019 February 2020 C D E F CTA Operations S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Division 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Group Days Off 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 t Alternate day off if 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 you work on this day 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 29 30 31 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 l Central offices closed 1 New Year’s Day 2 3 4 F G A B C D E 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 E F G A B C D 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 D E F G A B C Martin Luther 19 20 King, Jr. -

Melas, I & R Platoon, Hq

Recorded Interview Nashville 2009 _____________________________________________________________ Nicholas J. Melas, I & R Platoon, Hq. Co. 411th I was born and raised in Chicago and I am still living there. I am commonly known as Nick. I graduated from high school in June of 1941 and entered the University of Chicago in September. By December the quarter was ending and we were getting ready for the quarterly exams. I probably heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor at home over the radio. A couple of days later, along with two of my school friends, I decided to enlist in the U.S. Army. We felt that we had to do something. At the enlistment office they asked us what we were doing currently. We were told to stay in school and that we would be put in the ERC (Enlisted Reserve Corps). They told us, “When we need you we will call you.” So, we signed up in early December and went back to school. I had gone to the University of Chicago from an inner city high school, and was given a 1/3rd tuition scholarship. I had been on the high school wrestling team and had done pretty well in the Chicago area, so I became a member of the University’s wrestling team. In March of ’43, we got notification from the Army that they were giving us a thirty day notice to report for active duty. In the meantime, the other two fellows who had gone down with me originally to enlist, had just been admitted to medical school after two years of undergraduate work. -

Metropolitan Transit Research Study

Word Searchable Version not a True Copy National Transportation Library Section 508 and Accessibility Compliance The National Transportation Library (NTL) both links to and collects electronic documents in a variety of formats from a variety of sources. The NTL makes every effort to ensure that the documents it collects are accessible to all persons in accordance with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1998 (29 USC 794d), however, the NTL, as a library and digital repository, collects documents it does not create, and is not responsible for the content or form of documents created by third parties. Since June 21, 2001, all electronic documents developed, procured, maintained or used by the federal government are required to comply with the requirements of Section 508. If you encounter problems when accessing our collection, please let us know by writing to [email protected] or by contacting us at (800) 853- 1351. Telephone assistance is available 9AM to 6:30PM Eastern Time, 5 days a week (except Federal holidays). We will attempt to provide the information you need or, if possible, to help you obtain the information in an alternate format. Additionally, the NTL staff can provide assistance by reading documents, facilitate access to specialists with further technical information, and when requested, submit the documents or parts of documents for further conversion. Document Transcriptions In an effort to preserve and provide access to older documents, the NTL has chosen to selectively transcribe printed documents into electronic format. This has been achieved by making an OCR (optical character recognition) scan of a printed copy. -

BARRY S. SHANOFF Barry [email protected] CHICAGO

BARRY S. SHANOFF [email protected] CHICAGO TRANSIT AND INTERURBAN MEMORABIA Prices highlighted in green. Shipping extra. Chicago Transit Authority and Predecessors Chicago Motor Coach Company “Seeing Chicago the Motor Coach Way” Sights and attractions. Map opens to 18x11. Undated but appears c.1930. 30 “Guide to Coach Routes, Streetcar and Elevated Lines” Identifies and describes interurban lines, railroad stations, lake steamship lines, street directory, stores, amusements, points of interest. Interesting section illustrating onboard train route destination markers. 1926 35 Chicago Rapid Transit Company “Guide to Chicago” Listing of stations in each geographical division and branch of the system. 1924 15 “Chicago – What to See and How to Go” Sights and attractions. 1927 20 “L” Map of Chicago. Sights and attractions. Special focus on World’s Fair. Map opens to 20x14. 1933 25 “Travel Map & Guide to Chicago Attractions” Map opens to 20x13 and highlights World’s Fair “L” stations. 1933 25 “Chicago Rapid Transit Map” Facts, information, station descriptions. Map opens to 18x20. 1943 15 Chicago Surface Lines “How to See Chicago” Maps and sightseeing guide. Undated but c.1920 35 “Sight Seeing via Chicago Surface Lines” Map opens to 20x11. 1921 25 “Map Showing Rerouting of Cars on Chicago Surface Lines” Map unfolds to 20x10 with inset of central district (Loop area). Illinois Commerce Commission mandated new streetcar routes to improve traffic patterns and flow. New routes described. 1924 35 “Seeing Greater Chicago” Sightseeing and route guide. Map opens to 10x20. 1926, 1928 and 1929. Substantially the same content but vibrant color covers vary. 25 each “See Chicago and A Century of Progress Exposition” Sights and Attractions. -

Law, Politics, and Implementation of the Burnham Plan of Chicago Since 1909, 43 J

UIC Law Review Volume 43 Issue 2 Article 4 Winter 2010 Law as Hidden Architecture: Law, Politics, and Implementation of the Burnham Plan of Chicago Since 1909, 43 J. Marshall L. Rev. 375 (2010) Richard J. Roddewig Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Commercial Law Commons, Construction Law Commons, Judges Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard J. Roddewig, Law as Hidden Architecture: Law, Politics, and Implementation of the Burnham Plan of Chicago Since 1909, 43 J. Marshall L. Rev. 375 (2010) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss2/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW AS HIDDEN ARCHITECTURE: LAW, POLITICS, AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE BURNHAM PLAN OF CHICAGO SINCE 1909 RICHARD J. RODDEWIG,* J.D., MAI, CRE, FRICS PRESIDENT, CLARION ASSOCIATES, INC. I. THE BURNHAM PLAN AND THE PROGRESSIVE ERA: HAMILTONIAN DEMOCRATIC IDEALS IN 1909 CHICAGO Every one knows that the civic conditions which prevailed fifty years ago would not now be tolerated anywhere; and every one believes that conditions of to-day will not be tolerated by the men who shall follow us. This must be so, unless progress has ceased. The education of a community inevitably brings about a higher appreciation of the value of systematic improvement, and results in a strong desire on the part of the people to be surrounded by conditions in harmony with the growth of good taste .. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Postcards Collection 20Th Century

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Postcards Collection 20th century © 2016 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Scope Note 3 Subject Headings 3 INVENTORY 4 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.UCPOSTCARD Title University of Chicago. Postcards.Collection Date 20th century Size 1.5 linear feet (1 box) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract The collection contains postcards featuring the University of Chicago campus. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Postcards. Collection, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Scope Note The University of Chicago Postcards Collection contains posters featuring the University campus dating from the early through late 20th century. The postcards are organized by the building or area of campus depicted. The collection also includes postcards depicting the Chicago Theological Seminary, the Hyde Park neighborhood and surrounding areas and attractions (particularly Jackson and Washington Parks,) and a small number of other university campuses. Subject Headings • University of Chicago -- History • University of Chicago -- Buildings • • • Architecture -- Illinois -- Chicago 3 • Building -- Illinois -- Chicago -- History • College