Melas, I & R Platoon, Hq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law School Announcements 1965-1966 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 9-30-1965 Law School Announcements 1965-1966 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1965-1966" (1965). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 89. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/89 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements 1965-1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL Inquiries should be addressed as follows: Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and finan cial aid: For the J.D. Program: DEAN OF STUDENTS The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2406 For the Graduate Programs: ASSISTANT DEAN (GRADUATE STUDIES) The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2410 Housingfor Single Students: OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3149 Housingfor Married Students: OFFICE OF MARRIED STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 824 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone 752-3644 Payment of Fees and Deposits: THE BURSAR The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3146 The University of Chicago Founded by John D. -

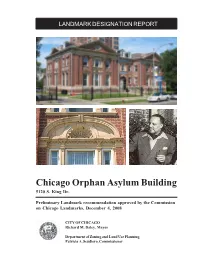

Orphan Asylum Building 5120 S

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Chicago Orphan Asylum Building 5120 S. King Dr. Preliminary Landmark recommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 4, 2008 CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Zoning and Land Use Planning Patricia A. Scudiero, Commissioner Cover illustrations Top: The Chicago Orphan Asylum Building. Left bottom: Detail of terra-cotta ornament. Right bottom: Horace Cayton, Jr., the director of the Parkway Community House, located in the building during the 1940s and early 1950s. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose ten members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recommend- ing to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. CHICAGO ORPHAN ASYLUM BUILDING (FORMERLY PARKWAY COMMUNITY HOUSE; NOW CHICAGO BAPTIST INSTITUTE) 5120 S. KING DR. BUILT: 1898-1899 ARCHITECTS:SHEPLEY, RUTAN, & COOLIDGE The Chicago Orphan Asylum Building (now the Chicago Baptist Institute) exemplifies multiple significant aspects of Chicago cultural and institutional history. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Postcards Collection 20Th Century

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Postcards Collection 20th century © 2016 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Scope Note 3 Subject Headings 3 INVENTORY 4 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.UCPOSTCARD Title University of Chicago. Postcards.Collection Date 20th century Size 1.5 linear feet (1 box) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract The collection contains postcards featuring the University of Chicago campus. Information on Use Access The collection is open for research. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. Postcards. Collection, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. Scope Note The University of Chicago Postcards Collection contains posters featuring the University campus dating from the early through late 20th century. The postcards are organized by the building or area of campus depicted. The collection also includes postcards depicting the Chicago Theological Seminary, the Hyde Park neighborhood and surrounding areas and attractions (particularly Jackson and Washington Parks,) and a small number of other university campuses. Subject Headings • University of Chicago -- History • University of Chicago -- Buildings • • • Architecture -- Illinois -- Chicago 3 • Building -- Illinois -- Chicago -- History • College -

Amos Alonzo Stagg's Contributions to Athletics

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1946 Amos Alonzo Stagg's Contributions to Athletics George Robert Coe University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons, History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Coe, George Robert. (1946). Amos Alonzo Stagg's Contributions to Athletics. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/1044 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMOS ALONZO STAGG'S CONTRIBUTIONS TO ATHLETICS By George Robert Coe •" Stockton 1946 Thesis Submitted to the Department of" Physical Education College of" the Pacii"ic In partial fulfillment of" the Requirements for the Degree of Master of" Arts APPROVED e..,_.e 1?JJ...an/ChaUimn or the Thesis Committee DEPOSITED m THE COLLEGE LIBRARY: ~!!. ~ DATED : YY/~ 11 /'itf-7 Librarian i CONTENTS Chapter Page Introduction • • •• . 1 I. Physical Educator. • 2 Originality in gymnasium construction. • • 2 Physical education requirements . • • • • 5 hysical education classes for ..omen • • . 7 lligh scholastic standards among athletes • 7 Physical examinations •• . 7 Knoles Field • . • . • 8 II. Football • • . .10 Tackling dummy • . ••. 10 Numbering of pl ayers . .• 10 Dividing gate receipts • . 11 Field House . 11 Order of the "C.. • . • . 12 The blanket a :~ard . 13 First game under lights. • . 13 Ends as halfbacks--origination of the wingback. -

Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Hutchins Administration Records 1892-1951

University of Chicago Library Guide to the University of Chicago Office of the President, Hutchins Administration Records 1892-1951 © 2007 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 6 Subject Headings 7 INVENTORY 7 Series I: General Files 7 Series II: Appointments and Budgets 158 Series III: Board of Trustees 181 Subseries 1: Subject Files 181 Subseries 2: Dockets 185 Series IV: Citizens' Board 186 Series V: Comptroller's Reports 193 Series VI: President's Report Files 193 Series VII: Lecture Arrangements 194 Series VIII: University of Chicago Settlement 197 Series IX: Oversize 197 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.OFCPRESHUTCHINS Title University of Chicago. Office of the President. Hutchins Administration. Records Date 1892-1951 Size 200.5 linear feet (394 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains records of the University of Chicago Office of the President, covering the administration of Robert M. Hutchins, who served as President from 1929-1945, then as Chancellor from 1945-1951, after the title of the office was changed. Included are administrative records such as correspondence, reports, publications, budgets and personnel material. Information on Use Access The records of the University of Chicago Office of the President, Hutchins Administration, contain no restrictions and are open for research in accordance with the University of Chicago Library's "Policies and Regulations Governing the Use of Manuscript and Archival Collections." Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: University of Chicago. -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II JUDSON’S WAR AND HUTCHINS’S PEACE: THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AND WAR IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER EDUCATIONXII XII THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Meteorology Training, Spring 1943. I JUDSON’S WAR AND I HUTCHINS’S PEACE: The University of Chicago and War in the Twentieth Century INTRODUCTION warm welcome to the new academic year. The Class of 2007, whose members are now in the middle of A their first quarter at the College, numbers 1,172 new first-year students. This represents the largest entering class in the history of the College, and it is also the size at which we will remain in order to achieve and maintain our goal of a College of 4,500 students. The total population of the College is now 4,375 students, almost 1,000 students more than we had ten years ago, in the autumn of 1993. The challenges that we have successfully addressed this academic year in teaching our first-year students are a reasonable measure of the challenges that our general-education programs will con- tinue to face in years to come, as we sustain a College of 4,500 students. The 1,172 members of the Class of 2007 were chosen from 9,100 applicants, of whom 40 percent were admitted. They join a College with a total enrollment of approximately 4,375 students. In comparison, the Class of 2003, which graduated a few months ago, was admitted from a pool of applicants 2,251 students smaller and had an admit rate of 48 percent. -

The College Magazine

In which we discuss SIX SCORE OF UCHICAGO FOOTBALL · THE HUNDREDS · ZELDA ET AL. Also “Themistocles, Thucydides ... ” · Unmemeable music · “A kitchen wench ... ” · A vaudeville clown THE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Winter 2020 Supplement to The University of Chicago Magazine COM-19_FY20 Core January Issue Cover_v5.indd 2 1/23/20 5:19 PM In November the Smart Museum hosted a silent disco inspired by the student- curated exhibition Down Time: On the Art . Photography by Erik Peterson Erik by Photography of Retreat i / The Core COM-19_FY20 Core January Issue TOC_v4.indd 1 1/23/20 4:02 PM From the editor IF YOU INSIDE DON’T HAVE SOMETHING NICE TO SAY ... SHORT Among the emails about the cheer “Themistocles, Thucydides …” that flooded my in-box in November Alumni memories: Tales of good cheer What’s new in the College: · 2 (see page 2), there was this UChicago’s own Shark Tank, The City in a Garden, Design Your Chicago, message: “I write not to share SSA’s new minor · UChicago creature: Very hungry squirrels a tale or a score for our fight song but a comment on the suggestions that Mr. Winter add words to his guitar compositions.” MEDIUM Like the cheer, guitarist Eli Winter, Class of 2020, was featured in the November issue Music: Guitarist Eli Winter, Class of 2020, has no words Comedy: “A · 6 of College Review, the Core’s kitchen wench is a kitchen wench forever!” · Books: Questions for Whet email newsletter. Although Moser, AB’04, and an excerpt from his guidebook Chicago: From Vision Winter is a creative writing to Metropolis major, his songs don’t have lyrics. -

The University of Chicago; an Official Guide

LD 931 1918 Copy 1 HE UNIVERSin OF CHICAGO An Official Guide KEY TO BUILDINGS Numbered in Chronological Order Oobb Lecture 15. Physiology 30. Lexington Hall Hall 16. Anatomy Bartlett Gymna- North Hall 17. Zoology sium Middle Divinity 18. Botany 32. Bel field Hall Hall 19. Ellis fiall 33. Boys' Clubhouse 4. South Divinity 20. Hitchcock Hall 34. Psychological Hall 21. The University Laboratories 5. Kent Chemical Press 35. Kimlmrk Hull Laboratory 22. Power House 36. Harper Memorial 6. Ryerson Physical 23. High School Library Laboratory Gymnasium 37. Athletic Grand- 7. Snell Hall 24. Emmons Blaine stand 38. Classics 8. Foster Hall 5Ia" „ „ 9. Beecher Hall 25. Hutchinson Hall 39. Hosenwald Hall 10. Kelly Hall 26. Reynolds Club 40. Ricketts Labora- 11. Green Hall 27. Mitchell Tower tory 12. Walker Museum 28. Mandel Assembly 41. Ida Noyes Hall 13. President's House Hall 42. Warehouse 14. Haskell Museum 29. Law School THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON AND EDINBURGH THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA TOKYO, OSAKA, KYOTO, FUKUOKA, SENDAI THE MISSION BOOK COMPANY Somen's The University of Chicago An Official Guide By DAVID ALLAN ROBERTSON Associate Professor of English Secretary to the President SECOND EDITION THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 'i\ v^^ .K^< c\\ Copyright 1916 and 1918 By The University of Chicago All Rights Reserved Published June 1916 Second Edition August 1918 h^^2 ISI8 ©CI.A502581 Composed and Printed By The University of Chicago Press Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. ^5 5* r TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE r Introduction i A Historical Sketch 2 • ^^ o ^ General Suggestions to Visitors 10 General Information 13 The Site 15 The University Architecture . -

The College Magazine

THE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Winter 2021 Supplement to The University of Chicago Magazine COM_21_FY21_CORE_February_2021_Cover_v8.indd 2 1/20/21 2:22 PM Tess Teodoro, Class of 2021, created this piece for the Autumn Quarter course Painting Matters: En Plein Air (see “When Art Imitates Life,” page 12). The assignment was to apply paint with Painting Teodoro, by Tess Class of 2021; photo illustration by Michael Vendiola anything except a brush. COM_21_FY21_CORE_February_2021_TOC_v7.indd 1 1/20/21 2:23 PM From the editor HOME INSIDE ALONE “How can you have a newspaper,” an anonymous SHORT commentator asked in the October 18, 1918, issue of the Daily Maroon, “when the Art: College students collaborate with world-renowned artist Jenny influenza does away with Holzer, EX’74, on LED trucks · Top 5: Scented candles that evoke 2 every sort of activity that Chicago neighborhoods Quote: “I am no longer an Episcopal priest ... ” ever happened?” · After an Autumn Quarter without sports, concerts, or parties, we might ask the MEDIUM same question. Even gossip was canceled, as Dean John W. Boyer, AM’69, PhD’75, UChicago creature: Pascal the ring-necked dove · UChicago history: observed: “No one gossips Songs of the University of Chicago, an unexpected pleasure in a difficult 4 on Zoom.” year · Faculty: In honor of the newly named Hanna Holborn Gray Three-quarters of College Special Collections Research Center, eight of our favorite HHG anecdotes students returned to Hyde Park, but they were almost · Public policy: What if cities took the lead on sustainability? invisible. Everywhere that students usually gather, this year they didn’t. -

Law School Announcements 1959-1960 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 8-31-1959 Law School Announcements 1959-1960 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1959-1960" (1959). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 49. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO FOUNDED BY JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER Announcements The Law School FOR SESSIONS OF 1959 • 1960 TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICERS OF ADMINISTRATION . OFFICERS OF INSTRUCTION . I. LoCATION, HISTORY, AND ORGANIZATION 3 II. GENERAL STATEMENT 4 III. ADMTSSTON OF STUDENTS . 4 Admission of Students to the Undergraduate (J.D.) Program . 4 Admission of Students to the Graduate (LL.M.) (l.S.D.) Program 5 Admission of Students to the Certificate Program. 5 Admission of Students to the Graduate Comparative Law and Foreign Law Programs . 5 IV. REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREES 5 The Undergraduate Program 5 The Graduate Program 6 The Certificate Program . 6 The Graduate Comparative Law Program (; The Foreign Law Program 7 V. EXAMINATIONS, GRADING, AND RULES 7 VI. COURSES OF TNSTRUCTTON . 8 First-Year Courses. 8 Second- and Third-Year Courses. 8 Seminars. 11 Courses for the Summer Session, 1959 13 Courses for the Summer Session, 1960 13 VII. -

EPTI Center, Glenview, Illinois

GENERAL ENERGY CORP. LEADERS IN ENGERY EFFICIENT DESIGN General Energy Corporation Engineers| Planners | Constructors 33 years of Excellence in Engineering General Energy About Us Corporation Engineers| Planners | Constructors • General Energy Corp. (GEC) serving the commercial, industrial and institutional clients for three decades providing energy efficient and sustainable designs • Our mission is to provide outstanding quality engineering services by means of innovation and continuous improvements • Knowledge, trust, and integrity are our values • Initiative, team work, planning, and execution are our strengths • Complete customer satisfaction is our goal www.Generalenergycorp.com General Energy Corporation Engineering Services Engineers| Planners | Constructors Feasibility Studies/ Life Cycle Cost Analysis Renewable/Green Energy Solutions Solar, Geothermal, Wind Design, Engineering/ Construction Documents Project Management Energy Star Certification LEED Design & Certification Commissioning www.generalenergycorp.com General Energy Corporation Energy Services Engineers| Planners | Constructors Develop a vision and operational plan to reduce energy usage Establish short term and long term energy goals Perform comprehensive energy efficiency assessment of your facility Identify all the energy savings opportunities and perform cost/benefit analysis of each opportunity Present our findings in a precise manner based upon factual data Assist in selection and implementation of projects Set-up, train, and facilitate energy cost reduction -

The Chicago Theological Seminary

a The Chicago Theological Seminary ANNUAL CATALOGUE SIXTY-FIFTH ACADEMIC YEAR 1922-1923 ANNOUNCEMENTS FOR 1923-1924 CHICAGO 5757 U NIVE'SlTY AVENUE Calendar 1923 June 3 Sunday Anniversary Sermon June 5 Tuesday Commencement June 13 Wednesday Spring Quarter Examinations begin June 15 Friday Spring Quarter ends June 18 Monday SUMMER QUARTER BEGINS July 4 Wednesday Independence day; a holiday July 24 Tuesday Examinations for the First Term July 25 Wednesday First Term of Summer ends July 26 Thursday Second Term of Summer begins Aug. 30 Thursday Examinations for Second Term Aug. 31 Friday Summer Quarter ends Oct. 1 Monday AUTUMN QUARTER BEGINS Nov. 29 Thursday Thanksgiving day; a holiday Dec. 19 Wednesday Autumn Quarter Examinations begin Dec. 21 Friday Autumn Quarter ends 1924 Jan. 2 Wednesday WINTER QUARTER BEGINS Feb. 12 Tuesday Lincoln's Birthday; a holiday Feb. 22 Friday Washington's Birthday; a holiday Mar. 19 Wednesday Winter Quarter Examinations begin Mar. 21 Friday Winter Quarter ends Mar. 31 Monday SPRING QUARTER BEGINS May 30 Friday Memorial Day; a holiday June 3 Tuesday Commencement June 11 Wednesday Spring Quarter Examinations begin June 13 Friday Spring Quarter ends • Board of Directors OFFICERS OZORA STEARNS DAVIS, Ph.D., D.O., LL.D.. President DAVID FALES, ESQ... ........................•....... Chairman JOHN R. MONTGOMERY, EsQ., _ Secretary WYLLYS W. BAIRD, EsQ .........................•..• _ Treasurer DIRECTORS Term of Office Expires in 1924 REV. G. GLENN ATKINS, D.O Detroit, Mich. PRESIDENT DONALD ]. COWLING ........•.•.• , .•...... Northfield, Minn. REV. THEODORE R. FAVILLE.. •••..••••.••• Oshkosh, Wis. REV. L. WENDELL FIFIELD ............•...•.•....... Sioux Falls, S. D. REV. ARCHIBALD HADDEN, D.D..... _ Muskegon, Mich.