Air Power the Agile Air Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

Battle of Britain Blood Red Skies

Battle of Britain Blood Red Skies (BRS) Campaign The German “Blitzkrieg”, a new way of waging “lightning war” had raged through first Poland, then in the early summer of 1940 struck at Holland, Belgium and France. The Luftwaffe (German air force) crushed all opponents in the air, and then fast moving armour with ever present air support sliced through ground forces leaving their opponents scrabbling to hold defensive positions that were already untenable. The British Expeditionary Force fell back to Dunkirk and was evacuated against the odds. During this period the RAF (Royal Air Force) had desperately tried to defend the Dunkirk beaches and the constant stream of ships large and small ferrying the remains of the BEF back home. When the last ships left over 338000 men had been evacuated, British and French, but they were exhausted and had abandoned all their weapons and heavy equipment on French roads and beaches. As Churchill said “What General Weygand has called the Battle of France is over ... the Battle of Britain is about to begin” The Battle of Britain was fought in the skies above England in the summer of 1940. The Luftwaffe were seeking to destroy the RAF to clear the way for a cross Chanel assault by the German Army. If they could succeed, Britain would be threatened with defeat and the war would be over. If the RAF could survive, then there may be time to prepare the defences, and possibly take the fight back to the enemy in due course. This campaign is designed to allow players to recreate some of the desperate battles fought in the summer of 1940 using the Blood Red Skies (BRS) rules from Warlord Games. -

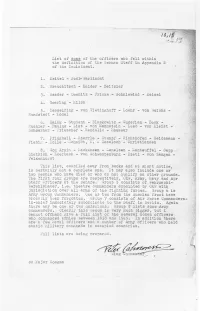

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

German Luftwaffe Fighter Forces, 31 May, Luftflotte Reich

German Luftwaffe Fighter Forces 31 May 1944 Luftflotte Reich Day Fighters Unit Type Strength Serviceable Stab/JG 1 Fw 190A 2 2 I/JG 1 Fw 190A 44 15 II/JG 1 Fw 190A 42 20 III/JG 1 Fw 190A 48 21 Stab/JG 3 Bf 109G 4 2 I/JG 3 Bf 109G 26 9 II/JG 3 Bf 109G 29 23 III/JG 3 Bf 109G 31 9 IV/JG 3 Fw 190A 54 1 I/JG 5 Bf 109G 43 36 II/JG 5 Bf 109G 44 36 Stab/JG 11 Bf 109G 4 3 I/JG 11 Fw 190A 28 20 II/JG 11 Bf 109G 31 14 III/JG 11 Fw 190A 28 11 10./JG 11 Fw 190A/Bf 109G 10 7 Stab/JG 27 Bf 109G 4 4 I/JG 27 Bf 109G 41 31 II/JG 27 Bf 109G 24 12 III/JG 27 Bf 109G 26 20 IV/JG 27 Bf 109G 18 12 II/JG 53 Bf 109G 31 14 III/JG 54 Fw 190A 23 8 JG 400 Me 163 10 0 Totals 645 330 II/JG 27 was reforming IV/JG 3 was forming as a Sturmstaffel JG 400 had not yet received any Komets. Zerstörers Unit Type Strength Serviceable II/ZG 1 Bf 110G 33 15 I/ZG 26 Me 410 20 6 II/ZG 26 Me 410 52 24 III/ZG 26 Me 262 6 1 I/ZG 76 Me 410 47 25 II/ZG 76 Me 410 36 0 Totals 194 71 III/ZG 26 and II/ZG 76 were reforming. -

Werksnummernliste Ju 52

www.Ju52archiv.de − Bernd Pirkl Weiter Krieg Wnr. Variante Kennzeichen Hersteller Erstbesitzer Zulassung Ergänzungen BNW Zulassungen überlebt FB Baltabol: 04.09.1935 FT-Flug, 25.09.1935 Nachflug , DVL-Testmaschine , 01.02.1938 Ankunft in Junkers Werft Leipzig zur Teilüberholung , 12/1938-10/1938 Lufthansa "Emil Schäfer" , 09/19369 zur Luftwaffe , 12.1941: 301 Ju 52/3mge D-ABUA ATG CB+EZ DVL/LUFTHANSA 09.1935 Luftverkehrsgruppe , 01.1942: Sanitätsflugbereitschaft 3 , 10.06.1942: Sanitätsflugbereitschaft 3 Artilleriebschuß auf dem Flug von Anissowo nach Gerodischtsche (100% zerstört) www.Ju52archiv.deFB Baltabol: 06.09.1935 Einflug, 27.09.1935 Nachflug , 12.1935: Umbau− mit 5 SesselnBernd mit Anschnallgurten sowie 8 Fenster fürPirkl Fliegerschule Neuruppin , 24.05.1943: 6./T.G.4 Insel Skyros Motlandung infolge 302 Ju 52/3mge D-ATYO ATG 06.09.1935 Brennstoffmangel (80% zerstört) FB Baltabol: 17.09.1935 Einflug, 07.10.1935 Nachflug , Reichseigenes Leihflugzeug der OMW Flugabteilung , Motorentestmaschine Mittelmotor Jumo 207/208/210/211/213 , FB Pohl: 12.04.1940 Überführung Rechlin-Dessau 303 Ju 52/3mge D-AMUY ATG NN+MA 17.09.1935 x , 05.1941: Überführungskommando Jüterbog , 23.12.1941: Überführungsstelle d. Lw. Jüterbog unfreiwillige Bodenberührung bei Klimbach (95% zerstört) 3 Tote: BF Uffz. Ludwig Piendel + 2 Zivilisten FB Baltabol: 02.10.1935 FT-Flug, 05.12.1935 Nachflug , FB Mühl: 22.+27.04.1938 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 02.05.1938 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 12.05.1938 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 19.05.1938 Probeflug 304 Ju 52/3mge WL-ADUO ATG D-ADUO LUFTWAFFE 30.09.1935 Staaken , FB Mühl: 25.05.1938 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 03.08.1938 Überlandflug Staaken-Bayreuth-Giebelstadt , FB Mühl: 05.08.1938 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 10.+13.+14.+24.+27.02.1939 Probeflug Staaken , FB Mühl: 16.+17.04.1939 Probeflug Staaken , F.F.S. -

© Osprey Publishing • © Osprey Publishing • HITLER’S EAGLES

www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com HITLER’S EAGLES THE LUFTWAFFE 1933–45 Chris McNab © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS Introduction 6 The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe 10 Luftwaffe – Organization and Manpower 56 Bombers – Strategic Reach 120 Fighters – Sky Warriors 174 Ground Attack – Strike from Above 238 Sea Eagles – Maritime Operations 292 Ground Forces – Eagles on the Land 340 Conclusion 382 Further Reading 387 Index 390 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION A force of Heinkel He 111s near their target over England during the summer of 1940. Once deprived of their Bf 109 escorts, the German bombers were acutely vulnerable to the predations of British Spitfires and Hurricanes. © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com he story of the German Luftwaffe (Air Force) has been an abiding focus of military Thistorians since the end of World War II in 1945. It is not difficult to see why. Like many aspects of the German war machine, the Luftwaffe was a crowning achievement of the German rearmament programme. During the 1920s and early 1930s, the air force was a shadowy organization, operating furtively under the tight restrictions on military development imposed by the Versailles Treaty. Yet through foreign-based aircraft design agencies, civilian air transport and nationalistic gliding clubs, the seeds of a future air force were nevertheless kept alive and growing in Hitler’s new Germany, and would eventually emerge in the formation of the Luftwaffe itself in 1935. The nascent Luftwaffe thereafter grew rapidly, its ranks of both men and aircraft swelling under the ambition of its commander-in-chief, Hermann Göring. -

Verbände Und Truppen Der Deutschen Wehrmacht Und Waffen SS Im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945

GEORG TESSIN Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 DRITTER BAND: Die Landstreitkräfte 6—14 Bearbeitet auf Grund der Unterlagen des Bundesarchiv-Militärarchivs Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung des Bundesarchivs und des Arbeitskreises für Wehrforschung VERLAG E. S. MITTLER & SOHN GMBH. • FRANKFURT/MAIN Vorwort zum 111. Band Die Herausgabc dieses bereits für 1966 geplanten Bandes hat sich durch den Tod des Verlegers verzögert. Es ist für mich ein tief gefühltes Bedürfnis, auch an dieser Stelle Herrn Dr. jur. Wilhelm Reibert, Oberst a. D. zu gedenken, der in seiner nimmermüden Einsatzbereitschaft für das militärische Schrift tum es übernommen hatte, dieses im Satz teure, im Absatz beschränkte und doch so notwendige Werk in einer des Verlages E. S. Mittler & Sohn würdigen Weise heraus zubringen. Bisher unbekannte, ungeordnet aus England zurückgekommene Akten des Ober kommandos der Luftwaffe in der Dokumentenzentrale des Militärgeschichtlichen Forschungsamtes in Freiburg brachten jetzt, 22 Jahre nach Kriegsende, wichtige Einzel heiten für die letzten Kriegsmonate, die in die kommenden Bände eingearbeitet, fin Band II und III jedoch nur nachträglich als Ergänzung hinzugefügt werden können. Mit der Herausgabe des I. Bandes dieses Werks, der außer den obersten Kommando behörden auch eine zusammenfassende Organisationsgeschichte nach Waffengattungen bringen wird, kann erst nach Fertigstellung des ganzen Manuskripts gerechnet werden Er wird bei der Herausgabe dann eingeschoben werden. Georg Tessin StadtbUcherei 47 Hamm 672794 ALLE RECHTE VORBEHALTEN COPYRIGHT BY E. S. MITTLER k SOHN GMBH, FRANKFURT/M. GESAMTHERSTELLUNG: H. G. CACHET * CO, LANGEN BEI FRANKFURT/M Gliederung Gliederung Sämtliche Verbände und Einheiten der Landstreitkräfte des Heeres, der Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe und Waffen-SS sind in / Nummernfolge geordnet. -

Readers' Guide

Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide Readers’ Guide Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide ABOUT THE NOVEL Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war (Winston Churchill) The hour will come when one of us will break—and it will not be National Socialist Germany (Adolf Hitler) And now the hour has come … It is August, 1940. Hitler’s triumphant Third Reich has crushed all Europe—except Britain. As Hitler launch- es a massive aerial assault, only the heavily outnumbered Fighter Command and the iron will of Winston Churchill can stop him. Johnnie Shaux, a Spitfire fighter pilot, must summon up the fortitude to fly into conditions in which death is all but inevitable, and continue to do so until the inevitable occurs... Eleanor Rand, a brilliant Fighter Command mathematician, must find her role in a man’s world. She studies the control room map tracking the ebbs and flows of the conflict, and sees the glimmerings of a radical break- through… Breaking Point is based on actual events in the Battle of Britain. The story alternates between Johnnie, face to face with the enemy, and Eleanor, using ‘zero-sum’ mathematical theory to evolve a strategic model of the battle. Their parallel stories merge as the battle reaches its climax and they confront danger together. Breaking Point — Readers’ Guide ABOUT THE AUTHOR John Rhodes was born in World War II while his father was serving at an RAF Fighter Command airfield in southern England. After the war he grew up in London, where, he says, the shells of bombed-out buildings ‘served as our adventure playgrounds.’ Rhodes graduated from Cambridge University where he studied history. -

267 Reichsverteidigung Am 15. September 1943 Wurde Mir

Abwärts Reichsverteidigung Am 15. September 1943 wurde mir befohlen, mich beim Luftwaffenbefehlshaber Mitte in Berlin als „I a Flieg“ zu melden. Bei diesem hohen Kommando liefen alle Fäden der Reichsverteidigung zusammen, von Luftschutz über Flak und Tagjagd bis hin zur Nacht- jagd. Seiner Bedeutung entsprechend, wurde es wenig später im Zuge einer größeren Re- organisation der Kommandostruktur der Luftwaffe in „Luftflotte Reich“ umbenannt. Befehlshaber war Generaloberst Hubert Weise, sein Stabschef Generalmajor Walter Boenicke, und als „I a Flak“ fungierte Oberst i. G. Schumann. Man hatte die Stelle des I a bewu§t geteilt, um beide Waffengattungen Ð Flak und Jagdflieger Ð jeweils durch einen ausgewiesenen Fachmann führen zu können. Schon sechs Wochen nach meinem Dienstantritt wurde General Boenicke versetzt und mit seinem Nachfolger, Generalleutnant Sigismund von Falkenstein, kam am 1. No- vember 1943 ein Vollblutflieger in den Stab, der voller Energie und Tatendrang an seine Aufgabe ging. Auch Generaloberst Weise wurde kurz vor Weihnachten 1943 zu einem neuen Kommando abberufen und durch Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff ersetzt, dem bisher die Luftflotte 5 in Norwegen Ð nun Kammhubers neue Verwendung Ð unterstan- den hatte. Erste und wichtigste Amtshandlung des neuen Befehlshabers war die Sorge für sein neues Zuhause. Er hatte während seiner Zeit in Skandinavien ein hübsches, geräumiges Blockhaus in der Nähe von Turku in Finnland bewohnt, an dem er sehr hing. So befahl er zur Erhaltung seiner persönlichen Kampfkraft, daß dieses schmucke Zuhause in Finnland zerlegt und auf einen Güterzug verladen werden solle, auf daß es ihm – neben unserem künftigen Gefechtsstand in Wannsee wieder errichtet – Zuflucht böte. Herr Generaloberst verfügten aber auch noch über einen sehr schönen Wagen, dem kein Leid geschehen sollte. -

Osprey Publishing • Aviation Elite Units Elite Aviation Jagdgeschwader ‘Nowotny’ Robert Forsyth

AEU 29 cover.qxd:AEU 29 cover.qxd 2/7/08 16:16 Page 1 OSPREY Aviation Elite Units • 29 Aviation Elite Units PUBLISHING Combat histories of the world’s most renowned Jagdgeschwader 7 Elite Aviation fighter and bomber units ‘Nowotny’ Jagdgeschwader 7 When the revolutionary Me 262 Units • jet fighter first appeared in the ‘Nowotny’ dangerous skies over northwest 29 Europe in mid-1944, it represented both a new dawn in Jagdgeschwader aeronautical development and the greatest challenge to Allied Colour aircraft profiles air superiority for a long time – and it came as a shock. Formed from the test unit Kommando Nowotny in mid-November 1944, and following rudimentary 7 training, Jagdgeschwader 7 ‘Nowotny’ became the world’s first truly operational jet unit of any size and significance. Despite its pilots still being uncertain of their awesome new aircraft, with its superior speed and armament, victories quickly followed against both US and British aircraft. By war’s end JG 7 had accounted for some 200 enemy aircraft shot Photographs Badges down in combat. Robert Forsyth I S B N 978-1-84603-320-9 OSPREY PUBLISHING www.ospreypublishing.com 9 781846 033209 O SPREY Robert Forsyth © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com AEU 29 pp001-005CORREX:AEU 29 16/6/08 11:18 Page 1 OSPREY Aviation Elite Units PUBLISHING Jagdgeschwader 7 ‘Nowotny’ © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com AEU 29 pp001-005CORREX:AEU 29 16/6/08 11:18 Page 2 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com AEU 29 pp001-005CORREX:AEU 29 16/6/08 11:18 Page 3 OSPREY Aviation -

Airpower Journal: Fall 1995, Volume IX, No. 3

Secretary of the Air Force Dr Sheila E. Widnall Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Ronald R. Fogleman Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Billy J. Boles Commander, Air University Lt Gen Jay W. Kelley Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col James C. Watkins Editor Lt Col James W. Spencer Associate Editor Maj John M. Poti Professional Staff Hugh Richardson, Contributing Editor Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Steven C. Garst, Director ofArt and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Thomas L. Howell, Prepress Production Manager The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innovative think- ing on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. The views and opinions expressed or im- plied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If they are reproduced, the Airpower Journal requests a cour- tesy line. JOURNAL Faj| J995 Vol. IX, No. 3 AFRP10-I FEATURES The Profession of Arms ..............................................4 Gen Ronald R. Fogleman, Chief of Staff, USAF The Airlift System: A Primer....................................16 Lt Col Robert C. Owen, USAF Towards a Seamless Mobility System: The C-130 and Air Force Reorganization............... -

Doctor Werner Schwerdtfeger a Short Biography

Doctor Werner Schwerdtfeger A Short Biography The Wetterflieger Project The Wetterflieger Project – Werner Schwerdtfeger Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Early Years ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Beginnings ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Researcher, Aeronaut, Teacher ................................................................................................................ 4 Warrior Years ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Weather Reconnaissance Meteorologist .................................................................................................. 9 Zentral Wetterdienst Gruppe ................................................................................................................. 13 Chef, Zentral Wetterdienst Gruppe .................................................................................................... 14 Normandy and the D-Day Forecast ..................................................................................................... 16 Ardennes Counteroffensive Forecast ................................................................................................