Doctor Werner Schwerdtfeger a Short Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

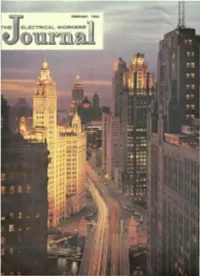

Electrical Workers'

FEBRUARY. 1963 ELECTRICAL WORKERS' O UR GOVERNMENT WORKERS The I nternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers has a significant segment of its membership-about 3O,OOO- working for "Uncle Sam." There IS hardly an agency of the Federal Government which does not need trained Electrical Workers to adequately carry out its purposes, and of course in some branches of Government their work is vital. In Shipyards, Naval Ordnancp. Plants, in various defense activities for example, electricians, linemen, power plant electricians, electronics, fire control, gyro and radio technical mechanics, electric crane operators, and others, are essential in carrying on the work of defending our nation and keeping its people safe. 18EW members work on board ships, on all types of transmission lines, in all kinds of shops, as mainlerlcllu.:;e rnell servicing Federal buildings and equipment, on communications work of every type. You will find them employed by the Army. the Navy, the Coast Guard, the Air Force, the Marine Corps, General Services Administration, the Federal Aviation Agency, Veterans Administration, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service, Census Bureau, Alaskan Railroad, Department of I nternal Revenue, Post Office Department, just to name a few. Of course the extensive work of IBEW members on such installations as the Tennessee Valley Authoritv. Bonneville Power and other Government projects throughout the country, is extremely well known. We could not mail a letter or spend a dollar bill if it were not for the Electrical Workers who keep the electronic machinery for printing stamps and currency in good running order, in the Bureau of Printing and Engraving. -

The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design: a Lasting Impact

The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design: A Lasting Impact MATTHEW BAILEY COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS The introduction of gunpowder did not immediately transform the battlefields of Europe. Designers of fortifications only had to respond to the destructive threats of siege warfare, and witnessing the technical failures of early gunpowder weaponry would hardly have convinced a European magnate to bolster his defenses. This essay follows the advancement of gunpowder tactics in late medieval and early Renaissance Europe. In particular, it focuses on Edward III’s employment of primitive ordnance during the Hundred Years’ War, the role of artillery in the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, and the organizational challenges of effectively implementing gunpowder as late as the end of the fifteenth century. This essay also seeks to illustrate the nature of the development of fortification in response to the emerging threat of gunpowder siege weaponry, including the architectural theories of the early Renaissance Italians, Henry VIII’s English artillery forts of the mid-sixteenth century, and the evolution of the angle bastion. The article concludes with a short discussion of the longevity and lasting relevance of the fortification technologies developed during the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. The castle was an inseparable component of medieval warfare. Since Duke William of Normandy’s 1066 conquest of Anglo-Saxon England, the construction of castles had become the earmark of medieval territorial expansion. These fortifications were not simply stone squares with round towers adorning the corners. Edward I’s massive castle building program in Wales, for example, resulted in fortifications so visually disparate that one might assume they were from different time periods.1 Medieval engineers had built upon castle technology for centuries by 1500, and the introduction of gunpowder weaponry to the battlefields of Europe foreshadowed a revision of the basics of fortress design. -

Findbuch Alpenfestung

Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort..................................................................................................................................................................... II 01. Dokumentarische Belege für die geplante Alpenfestung (Hofer, Kaltenbrunner und andere)............................1 01.01. Zeittafel zur Alpenfestung............................................................................................................................15 02. Kaltenbrunner und sein Festhalten an der Alpenfestung im Spiegelbild seiner angestrebten Verhandlungen mit den Westallierten...............................................................................................................................................19 03. Karl Wolff als Gegner der Alpenfestung und seine Verhandlungen mit Dulles................................................21 04. Hitler und die Alpenfestung.............................................................................................................................. 27 06. Die ??Wunderwaffe?? für die Alpenfestung - die ??Me 262??.........................................................................27 07. Geiseln (allgemein) für die Alpenfestung (Faustpfand für Verhandlungen aus dem letzten Rückzugsgebiet heraus)..................................................................................................................................................................... 40 08. ??Unternehmen?? Bernhard - Schloss Labers bei Meran (Falschgeld)........................................................... -

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644

A Contemporary Map of the Defences of Oxford in 1644 By R. T. LATTEY, E. J. S. PARSONS AND I. G. PHILIP HE student of the history of Oxford during the Civil War has always been T handicapped in dealing with the fortifications of the City, by the lack of any good contemporary map or plan. Only two plans purporting to show the lines constructed during the years 1642- 6 were known. The first of these (FIG. 24), a copper-engraving in the 'Wood collection,! is sketchy and ill-drawn, and half the map is upside-down. The second (FIG. 25) is in the Latin edition of Wood's History and Antiquities of the University of Oxford, published in 1674,2 and bears the title' Ichnographia Oxonire una cum Propugnaculis et Munimentis quibus cingebatur Aimo 1648.' The authorship of this plan has been attributed both to Richard Rallingson3 and to Henry Sherburne.' We know that Richard Rallingson drew a' scheme or plot' of the fortifications early in 1643,5 and Wood in his Athenae Oxomenses 6 states that Henry Sherburne drew' an exact ichno graphy of the city of Oxon, while it was a garrison for his Majesty, with all the fortifications, trenches, bastions, etc., performed for the use of Sir Thomas Glemham 7 the governor thereof, who shewing it to the King, he approved much of it, and wrot in it the names of the bastions with his own hand. This ichnography, or another drawn by Richard Rallingson, was by the care of Dr. John Fell engraven on a copper plate and printed, purposely to he remitted into Hist. -

German Air Forces Facing Britain, 18 August 1940

German Air Forces Facing Britain 18 August 1940 German High Command: Reichsmarschall H. Goering Luftflotte 2 (In Brussels) Generalfeldmarschall A. Kesselring Fliegerkorps I: (in Beauvais) Kampfgruppe 1 Staff (5/0 - He 111)(in Rosiéres-en-Santerre)1 I Gruppe (23/5 - He111)(in Montdidier) II Gruppe (25/5 - He111)(in Montdidier) III Gruppe (19/9 - He111)(in Rosiéres-en- Santerre) Kampfgruppe 76 Staff (3/2 - Do 17)(in Cormeilles-en-Vexin) I Gruppe (26/3 - Do 17)(in Beuvais) II Gruppe (29/8 - Do 17)(in Creil) III Gruppe (21/5 - Do 17)(in Cormeilles-en-Vexin) Fliegerkorps II (in Ghent) Kampfgruppe 2 Staff (4/1 - Do 17)(in Arras) I Gruppe (21/7 - Do 17)(in Epinoy) II Gruppe (31/3 - Do 17)(in Arras) III Gruppe (24/5 - Do 17)(in Cambrai) Kampfgruppe 3 Staff (5/1 - Do 17)(in Le Culot) I Gruppe (24/10 - Do 17)(in Le Culot) II Gruppe (27/7 - Do 17)(in Antwerp/Deurne) III Gruppe (29/5 - Do 17)(in St. Trond) Kampfgruppe 53 Staff (3/2 - He 111)(in Lille) I Gruppe (17/2 - He 111)(in Lille) II Gruppe (20/1 - He 111)(in Lille) III Gruppe (21/5 - He 111)(in Lille) II/Stukagruppe 1 (26/10 - Ju 87)(in Pas-de-Calais) IV/Stukagruppe 1 (16/10 - Ju 87)(in Tramecourt)2 Erprobungsgruppe 210 (Me 108 & Me 110) Fleigerdivision 9: (in Soesterberg) Kampfgruppe 4 Staff (5/1 - He 111)(in Soesterberg) I Gruppe (20/10 - He 111)(in Soesterberg) II Gruppe (23/7 - He 111)(in Eindhoven) III Gruppe (25/10 - Ju 88)(in Amsterdam/Schiphol) I/Kampfgruppe 40 (FW 200) Kampfgruppe 100 (He 111) Jagdfleigerfüher 2 (in Wissant) Jagdgruppe 3 Staff (2/0 - Me 109)(in Samer) 1 Numbers are serviceable and unservicable aircraft. -

Order of Battle, Mid-September 1940 Army Group a Commander-In-Chief

Operation “Seelöwe” (Sea Lion) Order of Battle, mid-September 1940 Army Group A Commander-in-Chief: Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt Chief of the General Staff: General der Infanterie Georg von Sodenstern Operations Officer (Ia): Oberst Günther Blumentritt 16th Army Commander-in-Chief: Generaloberst Ernst Busch Chief of the General Staff: Generalleutnant Walter Model Operations Officer (Ia): Oberst Hans Boeckh-Behrens Luftwaffe Commander (Koluft) 16th Army: Oberst Dr. med. dent. Walter Gnamm Division Command z.b.V. 454: Charakter als Generalleutnant Rudolf Krantz (This staff served as the 16th Army’s Heimatstab or Home Staff Unit, which managed the assembly and loading of all troops, equipment and supplies; provided command and logistical support for all forces still on the Continent; and the reception and further transport of wounded and prisoners of war as well as damaged equipment. General der Infanterie Albrecht Schubert’s XXIII Army Corps served as the 16th Army’s Befehlsstelle Festland or Mainland Command, which reported to the staff of Generalleutnant Krantz. The corps maintained traffic control units and loading staffs at Calais, Dunkirk, Ostend, Antwerp and Rotterdam.) FIRST WAVE XIII Army Corps: General der Panzertruppe Heinric h-Gottfried von Vietinghoff genannt Scheel (First-wave landings on English coast between Folkestone and New Romney) – Luftwaffe II./Flak-Regiment 14 attached to corps • 17th Infantry Division: Generalleutnant Herbert Loch • 35th Infantry Division: Generalleutnant Hans Wolfgang Reinhard VII Army -

Universidade Federal De Campina Grande Centro De Formação De Professores Unidade Acadêmica De Ciências Sociais Curso De Graduação Plena Em História

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE CAMPINA GRANDE CENTRO DE FORMAÇÃO DE PROFESSORES UNIDADE ACADÊMICA DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS CURSO DE GRADUAÇÃO PLENA EM HISTÓRIA “NÃO É A VERDADE QUE IMPORTA, MAS A VITÓRIA”: IMAGENS DE ADOLF HITLER NO CINEMA E NA HISTORIOGRAFIA (1900 – 1945) JOÃO BATISTA DIAS VIEIRA CAJAZEIRAS-PB 2017 JOÃO BATISTA DIAS VIEIRA “NÃO É A VERDADE QUE IMPORTA, MAS A VITÓRIA”: IMAGENS DE ADOLF HITLER NO CINEMA E NA HISTORIOGRAFIA (1900 – 1945) Monografia apresentada à disciplina Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (TCC), Graduação em História pela Unidade Acadêmica de Ciências Sociais, Centro de Formação de Professores, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande UFCG/PB, como requisito para obtenção de nota. Orientador: Prof. Ms. Isamarc Gonçalves Lôbo CAJAZEIRAS-PB 2017 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação-na-Publicação - (CIP) Josivan Coêlho dos Santos Vasconcelos - Bibliotecário CRB/15-764 Cajazeiras - Paraíba V658n Vieira, João Batista Dias. “Não é a verdade que importa, mas a vitória”: imagens de Adolf Hitler no cinema e na historiografia (1900 – 1945) / João Batista Dias Vieira. - Cajazeiras, 2017. 69f.: il. Bibliografia. Orientador: Prof. Ms. Lôbo, Isamarc Goncalves. Monografia (Licenciatura em História) UFCG/CFP, 2017. 1. Hitler. 2. História. 3. Cinema. 4. Nazismo. I. Isamarc Gonçalves Lôbo. II. Universidade Federal de Campina Grande. III. Centro de Formação de Professores. IV. Título. UFCG/CFP/BS CDU - 929 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço primeiramente a Deus por me conceder sabedoria, saúde e ter me dado forças para alcançar tal objetivo. Agradeço também a minha família pelos incentivos constantes. A minha esposa que sempre me incentivou e foi compreensiva nos momentos difíceis, aos meus filhos pela ajuda dada nos momentos em que precisei e foram grandes incentivadores. -

For People Who Love Early Maps Early Love Who People for 143 No

143 INTERNATIONAL MAP COLLECTORS’ SOCIETY WINTER 2015 No.143 FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS JOURNAL ADVERTISING Index of Advertisers 4 issues per year Colour B&W Altea Gallery 57 Full page (same copy) £950 £680 Half page (same copy) £630 £450 Art Aeri 47 Quarter page (same copy) £365 £270 Antiquariaat Sanderus 36 For a single issue 22 Full page £380 £275 Barron Maps Half page £255 £185 Barry Lawrence Ruderman 4 Quarter page £150 £110 Flyer insert (A5 double-sided) £325 £300 Collecting Old Maps 10 Clive A Burden 2 Advertisement formats for print Daniel Crouch Rare Books 58 We can accept advertisements as print ready artwork saved as tiff, high quality jpegs or pdf files. Dominic Winter 36 It is important to be aware that artwork and files Frame 22 that have been prepared for the web are not of sufficient quality for print. Full artwork Gonzalo Fernández Pontes 15 specifications are available on request. Jonathan Potter 42 Advertisement sizes Kenneth Nebenzahl Inc. 47 Please note recommended image dimensions below: Kunstantiquariat Monika Schmidt 47 Full page advertisements should be 216 mm high Librairie Le Bail 35 x 158 mm wide and 300–400 ppi at this size. Loeb-Larocque 35 Half page advertisements are landscape and 105 mm high x 158 mm wide and 300–400 ppi at this size. The Map House inside front cover Quarter page advertisements are portrait and are Martayan Lan outside back cover 105 mm high x 76 mm wide and 300–400 ppi at this size. Mostly Maps 15 Murray Hudson 10 IMCoS Website Web Banner £160* The Observatory 35 * Those who advertise in the Journal may have a web banner on the IMCoS website for this annual rate. -

Battle of Britain Blood Red Skies

Battle of Britain Blood Red Skies (BRS) Campaign The German “Blitzkrieg”, a new way of waging “lightning war” had raged through first Poland, then in the early summer of 1940 struck at Holland, Belgium and France. The Luftwaffe (German air force) crushed all opponents in the air, and then fast moving armour with ever present air support sliced through ground forces leaving their opponents scrabbling to hold defensive positions that were already untenable. The British Expeditionary Force fell back to Dunkirk and was evacuated against the odds. During this period the RAF (Royal Air Force) had desperately tried to defend the Dunkirk beaches and the constant stream of ships large and small ferrying the remains of the BEF back home. When the last ships left over 338000 men had been evacuated, British and French, but they were exhausted and had abandoned all their weapons and heavy equipment on French roads and beaches. As Churchill said “What General Weygand has called the Battle of France is over ... the Battle of Britain is about to begin” The Battle of Britain was fought in the skies above England in the summer of 1940. The Luftwaffe were seeking to destroy the RAF to clear the way for a cross Chanel assault by the German Army. If they could succeed, Britain would be threatened with defeat and the war would be over. If the RAF could survive, then there may be time to prepare the defences, and possibly take the fight back to the enemy in due course. This campaign is designed to allow players to recreate some of the desperate battles fought in the summer of 1940 using the Blood Red Skies (BRS) rules from Warlord Games. -

106 German and British Adaptations and the Context of German Strategic Decision Making in 1940-41 Williamson Murray Historians U

German and British Adaptations and the Context of German Strategic Decision Making in 1940-41 Williamson Murray Historians usually characterize the Battle of Britain as a great contest between the Luftwaffe and RAF Fighter Command that lasted from early July 1940 through to the massive daylight bombing of London during the first two weeks of September. The RAF is slightly more generous in placing the dates for the battle as occurring between 10 July and 15 October 1940.1 But the long and short of it is that the historical focus has emphasized the daylight, air-to-air struggle that took place over the course of three months: July, August, and September, 1940. This article, however aims at examining adaptation over a wider space of time – from early June 1940 through to the end of May 1941, when the Wehrmacht turned east with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union and what the Luftwaffe’s chief of staff termed “a proper war.”2 It also aims at examining adaptation on both sides in the areas of technology, intelligence, operations, and tactics, rather than simply the contest between British fighters and German bombers and fighters – although the latter is obviously of considerable importance. Moreover, it will also examine the questions surrounding the larger strategic issues of German efforts to besiege the British Isles over the course of 1940 and the first half of 1941. The period of the Anglo-German war between the fall of France and the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 is of particular interest because it involved the integration of a whole set of new technologies and concepts into conflict as well as the adaptation to a complex set of problems that those new technologies raised, the answers to which were largely ambiguous. -

World Resource Review

REPRINT FROM World Resource Review volume 7 number 4 COPYRIGHT(C) WORLD RESOURCE REVIEW, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Send all correspondence regarding WORLD RESOURCE REVIEW 1995 to WORLD RESOURCE REVIEW, PO BOX WOODRIDGE IL USA 5275, 60517-0275, World Resource Review Vol. 7 No. 4 THE 19TH CENTURY DISCUSSION OF CLIMATE VARIABILITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE: ANALOGIES FOR THE PRESENT DEBATE'! Nico Stehr Department of Sociology The University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2H4 CANADA Hans von Storch and Moritz Flligel Max-Planck-Institut fUr Meteorologie Bundesstr. 55, D-20146 Hamburg GERMANY Keywords: Climate Change, Natural Variability, Political Responses, Social, Political and Economic Consequences, Anthropogenic Change, Public Discourse ABSTRACT Toward the end of the nineteenth and at the beginning of twentieth century significant discussions occurred among geographers, meteorologists and "climatologists" concerned with the notion of climate variability (Klimaschwankungen) and anthropogenic climate change (Klimawandel! Klimaanderungen), for instance, due to deforestation and reforestation. We identify two protagonists of this debate, Eduard Brlickner and Julius Hann, who both accept the notion of climate variability on the decada1 scale, but respond in very different ways to the discovery of climate change. Brlickner assessed the impact of climate variability on society (e.g., on health, the balance of trade, emigration to the USA), and tried to bring these to the attention of the public, whereas Hann limited himself to the immediate natural scientific