An Emerging Role for Calcium Signalling in Innate And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclin K Interacts with Β-Catenin to Induce Cyclin D1 Expression And

Theranostics 2020, Vol. 10, Issue 24 11144 Ivyspring International Publisher Theranostics 2020; 10(24): 11144-11158. doi: 10.7150/thno.42578 Research Paper Cyclin K interacts with β-catenin to induce Cyclin D1 expression and facilitates tumorigenesis and radioresistance in lung cancer Guojun Yao*, Jing Tang*, Xijie Yang, Ye Zhao, Rui Zhou, Rui Meng, Sheng Zhang, Xiaorong Dong, Tao Zhang, Kunyu Yang, Gang Wu and Shuangbing Xu Cancer Center, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China. *These authors contributed equally to this work. Corresponding author: Shuangbing Xu or Gang Wu, Cancer Center, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. © The author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2019.11.29; Accepted: 2020.08.24; Published: 2020.09.11 Abstract Rationale: Radioresistance remains the major cause of local relapse and distant metastasis in lung cancer. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly defined. This study aimed to investigate the role and regulatory mechanism of Cyclin K in lung cancer radioresistance. Methods: Expression levels of Cyclin K were measured by immunohistochemistry in human lung cancer tissues and adjacent normal lung tissues. Cell growth and proliferation, neutral comet and foci formation assays, G2/M checkpoint and a xenograft mouse model were used for functional analyses. Gene expression was examined by RNA sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Download Download

Supplementary Figure S1. Results of flow cytometry analysis, performed to estimate CD34 positivity, after immunomagnetic separation in two different experiments. As monoclonal antibody for labeling the sample, the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- conjugated mouse anti-human CD34 MoAb (Mylteni) was used. Briefly, cell samples were incubated in the presence of the indicated MoAbs, at the proper dilution, in PBS containing 5% FCS and 1% Fc receptor (FcR) blocking reagent (Miltenyi) for 30 min at 4 C. Cells were then washed twice, resuspended with PBS and analyzed by a Coulter Epics XL (Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, FL, USA) flow cytometer. only use Non-commercial 1 Supplementary Table S1. Complete list of the datasets used in this study and their sources. GEO Total samples Geo selected GEO accession of used Platform Reference series in series samples samples GSM142565 GSM142566 GSM142567 GSM142568 GSE6146 HG-U133A 14 8 - GSM142569 GSM142571 GSM142572 GSM142574 GSM51391 GSM51392 GSE2666 HG-U133A 36 4 1 GSM51393 GSM51394 only GSM321583 GSE12803 HG-U133A 20 3 GSM321584 2 GSM321585 use Promyelocytes_1 Promyelocytes_2 Promyelocytes_3 Promyelocytes_4 HG-U133A 8 8 3 GSE64282 Promyelocytes_5 Promyelocytes_6 Promyelocytes_7 Promyelocytes_8 Non-commercial 2 Supplementary Table S2. Chromosomal regions up-regulated in CD34+ samples as identified by the LAP procedure with the two-class statistics coded in the PREDA R package and an FDR threshold of 0.5. Functional enrichment analysis has been performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) -

Supp Table 1.Pdf

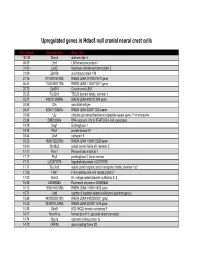

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

G PROTEIN-COUPLED RECEPTORS Overview:- The completion of the Human Genome Project allowed the identification of a large family of proteins with a common motif of seven groups of 20-24 hydrophobic amino acids arranged as α-helices. Approximately 800 of these seven transmembrane (7TM) receptors have been identified of which over 300 are non-olfactory receptors (see Frederikson et al., 2003; Lagerstrom and Schioth, 2008). Subdivision on the basis of sequence homology allows the definition of rhodopsin, secretin, adhesion, glutamate and Frizzled receptor families. NC-IUPHAR recognizes Classes A, B, and C, which equate to the rhodopsin, secretin, and glutamate receptor families. The nomenclature of 7TM receptors is commonly used interchangeably with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), although the former nomenclature recognises signalling of 7TM receptors through pathways not involving G proteins. For example, adiponectin and membrane progestin receptors have some sequence homology to 7TM receptors but signal independently of G-proteins and appear to reside in membranes in an inverted fashion compared to conventional GPCR. Additionally, the NPR-C natriuretic peptide receptor has a single transmembrane domain structure, but appears to couple to G proteins to generate cellular responses. The 300+ non-olfactory GPCR are the targets for the majority of drugs in clinical usage (Overington et al., 2006), although only a minority of these receptors are exploited therapeutically. Signalling through GPCR is enacted by the activation of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins), made up of α, β and γ subunits, where the α and βγ subunits are responsible for signalling. The α subunit (tabulated below) allows definition of one series of signalling cascades and allows grouping of GPCRs to suggest common cellular, tissue and behavioural responses. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Convergent Molecular, Cellular, and Cortical Neuroimaging Signatures of Major Depressive Disorder

Convergent molecular, cellular, and cortical neuroimaging signatures of major depressive disorder Kevin M. Andersona,1, Meghan A. Collinsa, Ru Kongb,c,d,e,f, Kacey Fanga, Jingwei Lib,c,d,e,f, Tong Heb,c,d,e,f, Adam M. Chekroudg,h, B. T. Thomas Yeob,c,d,e,f,i, and Avram J. Holmesa,g,j aDepartment of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; bDepartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore; cCentre for Sleep and Cognition, National University of Singapore, Singapore; dClinical Imaging Research Centre, National University of Singapore, Singapore; eN.1 Institute for Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore; fInstitute for Digital Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; gDepartment of Psychiatry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; hSpring Health, New York, NY 10001; iGraduate School for Integrative Sciences and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore; and jDepartment of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114 Edited by Huda Akil, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and approved August 12, 2020 (received for review May 5, 2020) Major depressive disorder emerges from the complex interactions detail. To date, there have been few opportunities to directly of biological systems that span genes and molecules through cells, explore the depressive phenotype across levels of analysis—from networks, and behavior. Establishing how neurobiological pro- genes and molecules through cells, circuits, networks, and cesses coalesce to contribute to depression requires a multiscale behavior—simultaneously (14). approach, encompassing measures of brain structure and function In vivo neuroimaging has identified depression-related corre- as well as genetic and cell-specific transcriptional data. -

Downregulation of Carnitine Acyl-Carnitine Translocase by Mirnas

Page 1 of 288 Diabetes 1 Downregulation of Carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase by miRNAs 132 and 212 amplifies glucose-stimulated insulin secretion Mufaddal S. Soni1, Mary E. Rabaglia1, Sushant Bhatnagar1, Jin Shang2, Olga Ilkayeva3, Randall Mynatt4, Yun-Ping Zhou2, Eric E. Schadt6, Nancy A.Thornberry2, Deborah M. Muoio5, Mark P. Keller1 and Alan D. Attie1 From the 1Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin; 2Department of Metabolic Disorders-Diabetes, Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, New Jersey; 3Sarah W. Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center, Duke Institute of Molecular Physiology, 5Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Durham, North Carolina. 4Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University system, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; 6Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York. Corresponding author Alan D. Attie, 543A Biochemistry Addition, 433 Babcock Drive, Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, (608) 262-1372 (Ph), (608) 263-9608 (fax), [email protected]. Running Title: Fatty acyl-carnitines enhance insulin secretion Abstract word count: 163 Main text Word count: 3960 Number of tables: 0 Number of figures: 5 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online June 26, 2014 Diabetes Page 2 of 288 2 ABSTRACT We previously demonstrated that micro-RNAs 132 and 212 are differentially upregulated in response to obesity in two mouse strains that differ in their susceptibility to obesity-induced diabetes. Here we show the overexpression of micro-RNAs 132 and 212 enhances insulin secretion (IS) in response to glucose and other secretagogues including non-fuel stimuli. We determined that carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase (CACT, Slc25a20) is a direct target of these miRNAs. -

Oligodendrocytes Remodel the Genomic Fabrics of Functional Pathways in Astrocytes

1 Article 2 Oligodendrocytes remodel the genomic fabrics of 3 functional pathways in astrocytes 4 Dumitru A Iacobas 1,2,*, Sanda Iacobas 3, Randy F Stout 4 and David C Spray 2,5 5 Supplementary Material 6 Table S1. Genes whose >1.5x absolute fold-change did not meet the individual CUT criterion. 7 Red/green background of the expression ratio indicates not significant (false) up-/down-regulation. Gene Description X CUT Acap2 ArfGAP with coiled-coil, ankyrin repeat and PH domains 2 -1.540 1.816 Adamts18 a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase -1.514 1.594 Akr1c12 aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C12 1.866 1.994 Alx3 aristaless-like homeobox 3 1.536 1.769 Alyref2 Aly/REF export factor 2 -1.880 2.208 Ankrd33b ankyrin repeat domain 33B 1.593 1.829 Ankrd45 ankyrin repeat domain 45 1.514 1.984 Ankrd50 ankyrin repeat domain 50 1.628 1.832 Ankrd61 ankyrin repeat domain 61 1.645 1.802 Arid1a AT rich interactive domain 1A -1.668 2.066 Artn artemin 1.524 1.732 Aspm abnormal spindle microtubule assembly -1.693 1.716 Atp6v1e1 ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit E1 -1.679 1.777 Bag4 BCL2-associated athanogene 4 1.723 1.914 Birc3 baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 -1.588 1.722 Ccdc104 coiled-coil domain containing 104 -1.819 2.130 Ccl2 chemokine -1.699 2.034 Cdc20b cell division cycle 20 homolog B 1.512 1.605 Cenpf centromere protein F 2.041 2.128 Cep97 centrosomal protein 97 -1.641 1.723 COX1 mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase I -1.607 1.650 Cpsf7 cleavage and polyadenylation specific factor 7 -1.635 1.891 Crct1 cysteine-rich -

Hypoxia Transcriptomic Modifications Induced by Proton Irradiation In

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article Hypoxia Transcriptomic Modifications Induced by Proton Irradiation in U87 Glioblastoma Multiforme Cell Line Valentina Bravatà 1,2,† , Walter Tinganelli 3,†, Francesco P. Cammarata 1,2,* , Luigi Minafra 1,2,* , Marco Calvaruso 1,2 , Olga Sokol 3 , Giada Petringa 2, Giuseppe A.P. Cirrone 2, Emanuele Scifoni 4 , Giusi I. Forte 1,2,‡ and Giorgio Russo 1,2,‡ 1 Institute of Molecular Bioimaging and Physiology–National Research Council (IBFM-CNR), 90015 Cefalù, Italy; [email protected] (V.B.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (G.I.F.); [email protected] (G.R.) 2 Laboratori Nazionali del SUD, Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (LNS-INFN), 95100 Catania, Italy; [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (G.A.P.C.) 3 Biophysics Department, GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung GmbH, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany; [email protected] (W.T.); [email protected] (O.S.) 4 Trento Institute for Fundamental Physics and Applications (TIFPA), Istituto Nazionale Fisica Nucleare (INFN), 38123 Trento, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.P.C.); [email protected] (L.M.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. ‡ These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: In Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM), hypoxia is associated with radioresistance and poor prognosis. Since standard GBM treatments are not always effective, new strategies are needed Citation: Bravatà, V.; Tinganelli, W.; to overcome resistance to therapeutic treatments, including radiotherapy (RT). Our study aims Cammarata, F.P.; Minafra, L.; to shed light on the biomarker network involved in a hypoxic (0.2% oxygen) GBM cell line that Calvaruso, M.; Sokol, O.; Petringa, G.; is radioresistant after proton therapy (PT). -

GSE50161, (C) GSE66354, (D) GSE74195 and (E) GSE86574

Figure S1. Boxplots of normalized samples in five datasets. (A) GSE25604, (B) GSE50161, (C) GSE66354, (D) GSE74195 and (E) GSE86574. The x‑axes indicate samples, and the y‑axes represent the expression of genes. Figure S2. Volanco plots of DEGs in five datasets. (A) GSE25604, (B) GSE50161, (C) GSE66354, (D) GSE74195 and (E) GSE86574. Red nodes represent upregulated DEGs and green nodes indicate downregulated DEGs. Cut‑off criteria were P<0.05 and |log2 FC|>1. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FC, fold change; adj.P.Val, adjusted P‑value. Figure S3. Transcription factor‑gene regulatory network constructed using the Cytoscape iRegulion plug‑in. Table SI. Primer sequences for reverse transcription‑quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Genes Sequences hsa‑miR‑124 F: 5'‑ACACTCCAGCTGGGCAGCAGCAATTCATGTTT‑3' R: 5'‑CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGA‑3' hsa‑miR‑330‑3p F: 5'‑CATGAATTCACTCTCCCCGTTTCTCCCTCTGC‑3' R: 5'‑CCTGCGGCCGCGAGCCGCCCTGTTTGTCTGAG‑3' hsa‑miR‑34a‑5p F: 5'‑TGGCAGTGTCTTAGCTGGTTGT‑3' R: 5'‑GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGAC‑3' hsa‑miR‑449a F: 5'‑TGCGGTGGCAGTGTATTGTTAGC‑3' R: 5'‑CCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT‑3' CD44 F: 5'‑CGGACACCATGGACAAGTTT‑3' R: 5'‑TGTCAATCCAGTTTCAGCATCA‑3' PCNA F: 5'‑GAACTGGTTCATTCATCTCTATGG‑3' F: 5'‑TGTCACAGACAAGTAATGTCGATAAA‑3' SYT1 F: 5'‑CAATAGCCATAGTCGCAGTCCT‑3' R: 5'‑TGTCAATCCAGTTTCAGCATCA‑3' U6 F: 5'‑GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT‑3' R: 5'‑CGCTTCACGAATTTGCGTGTCAT‑3' GAPDH F: 5'‑GGAAAGCTGTGGCGTGAT‑3' R: 5'‑AAGGTGGAAGAATGGGAGTT‑3' hsa, homo sapiens; miR, microRNA; CD44, CD44 molecule (Indian blood group); PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; -

List of Predicted Circfam120a Target Mrnas Gene in Pathway Species Gene Name

List of predicted circFAM120A target mRNAs Gene in pathway Species Gene name HRAS Homo sapiens HRas proto-oncogene, GTPase (HRAS) ADCY1 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 1 (ADCY1) ADCY2 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 2 (ADCY2) ADCY7 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 7 (ADCY7) PTGS2 Homo sapiens Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) PGF Homo sapiens Placental growth factor (PGF) ADCY5 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 5 (ADCY5) STAT5A Homo sapiens Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5A (STAT5A) ADCY6 Homo sapiens Adenylate cyclase 6 (ADCY6) STAT5B Homo sapiens Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B (STAT5B) LPAR3 Homo sapiens Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 (LPAR3) LPAR2 Homo sapiens Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 2 (LPAR2) CTNNB1 Homo sapiens Catenin beta 1 (CTNNB1) CUL2 Homo sapiens Cullin 2 (CUL2) RARA Homo sapiens Retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARA) GNG2 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 2 (GNG2) RARB Homo sapiens Retinoic acid receptor beta (RARB) GNG3 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 3 (GNG3) FAS Homo sapiens Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS) GNG4 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 4 (GNG4) GNG7 Homo sapiens G protein subunit gamma 7 (GNG7) PIK3CG Homo sapiens Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma (PIK3CG) WNT10B Homo sapiens Wnt family member 10B (WNT10B) BCR Homo sapiens BCR, RhoGEF and GTPase activating protein (BCR) BRAF Homo sapiens B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) RXRB Homo sapiens Retinoid X receptor beta (RXRB) ROCK2 Homo sapiens Rho