Convergent Molecular, Cellular, and Cortical Neuroimaging Signatures of Major Depressive Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Loss-Of-Function Allele of a TAC1-Like Gene (Sltac1) Located on Tomato Chromosome 10 Is a Candidate for the Erectoid Leaf (Erl) Mutation

A loss-of-function allele of a TAC1-like gene (SlTAC1) located on tomato chromosome 10 is a candidate for the Erectoid leaf (Erl) mutation Matías González-Arcos1*; Maria Esther de Noronha Fonseca2 Daniel Basílio Zandonadi3; Lázaro E. P. Peres4; Ana Arruabarrena1; Demetryus S. Ferreira5; Zoltan Kevei5; Fady Mohareb5; Andrew J. Thompson5 & Leonardo S. Boiteux2 1National Research Program on Horticultural Production, National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIA), Estación Experimental INIA Salto Grande, CP 50000, Salto, Uruguay. 2Nacional Center for Vegetable Crops Research (CNPH) – Embrapa Vegetable Crops (Hortaliças), Brasília–DF, Brazil. 3Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Nupem, 27965045, Macaé–RJ, Brazil. 4Laboratory of Hormonal Control of Plant Development, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Escola Superior de Agricultura Luiz de Queiroz, Universidade de São Paulo (ESALQ/USP), Piracicaba–SP, Brazil. 5Cranfield Soil and Agrifood Institute, Cranfield University, Cranfield, MK43 0AL, UK. *Corresponding author ([email protected]) Acknowledgements This work was done in the context of MG-A doctoral studies program at the Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de la República Oriental del Uruguay. We thank A. Manzzioni, I. Laxague and N. Zunini of INIA Salto Grande, and W. P. Dutra and A. F. Costa of Embrapa Vegetable Crops, for their assistance in conducting some of the experiments. LSB and MENF were supported by CNPq and CAPES grants. AJT and FM were supported by BBSRC Research Grant BB/L011611/1. SUMMARY The genetic basis of an erectoid leaf phenotype was investigated in distinct tomato breeding populations, including one derived from Solanum lycopersicum ‘LT05’ (with the erectoid leaf phenotype and uniform ripening, genotype uu) × S. -

Cyclin K Interacts with Β-Catenin to Induce Cyclin D1 Expression And

Theranostics 2020, Vol. 10, Issue 24 11144 Ivyspring International Publisher Theranostics 2020; 10(24): 11144-11158. doi: 10.7150/thno.42578 Research Paper Cyclin K interacts with β-catenin to induce Cyclin D1 expression and facilitates tumorigenesis and radioresistance in lung cancer Guojun Yao*, Jing Tang*, Xijie Yang, Ye Zhao, Rui Zhou, Rui Meng, Sheng Zhang, Xiaorong Dong, Tao Zhang, Kunyu Yang, Gang Wu and Shuangbing Xu Cancer Center, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China. *These authors contributed equally to this work. Corresponding author: Shuangbing Xu or Gang Wu, Cancer Center, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. © The author(s). This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). See http://ivyspring.com/terms for full terms and conditions. Received: 2019.11.29; Accepted: 2020.08.24; Published: 2020.09.11 Abstract Rationale: Radioresistance remains the major cause of local relapse and distant metastasis in lung cancer. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly defined. This study aimed to investigate the role and regulatory mechanism of Cyclin K in lung cancer radioresistance. Methods: Expression levels of Cyclin K were measured by immunohistochemistry in human lung cancer tissues and adjacent normal lung tissues. Cell growth and proliferation, neutral comet and foci formation assays, G2/M checkpoint and a xenograft mouse model were used for functional analyses. Gene expression was examined by RNA sequencing and quantitative real-time PCR. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Download Download

Supplementary Figure S1. Results of flow cytometry analysis, performed to estimate CD34 positivity, after immunomagnetic separation in two different experiments. As monoclonal antibody for labeling the sample, the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- conjugated mouse anti-human CD34 MoAb (Mylteni) was used. Briefly, cell samples were incubated in the presence of the indicated MoAbs, at the proper dilution, in PBS containing 5% FCS and 1% Fc receptor (FcR) blocking reagent (Miltenyi) for 30 min at 4 C. Cells were then washed twice, resuspended with PBS and analyzed by a Coulter Epics XL (Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, FL, USA) flow cytometer. only use Non-commercial 1 Supplementary Table S1. Complete list of the datasets used in this study and their sources. GEO Total samples Geo selected GEO accession of used Platform Reference series in series samples samples GSM142565 GSM142566 GSM142567 GSM142568 GSE6146 HG-U133A 14 8 - GSM142569 GSM142571 GSM142572 GSM142574 GSM51391 GSM51392 GSE2666 HG-U133A 36 4 1 GSM51393 GSM51394 only GSM321583 GSE12803 HG-U133A 20 3 GSM321584 2 GSM321585 use Promyelocytes_1 Promyelocytes_2 Promyelocytes_3 Promyelocytes_4 HG-U133A 8 8 3 GSE64282 Promyelocytes_5 Promyelocytes_6 Promyelocytes_7 Promyelocytes_8 Non-commercial 2 Supplementary Table S2. Chromosomal regions up-regulated in CD34+ samples as identified by the LAP procedure with the two-class statistics coded in the PREDA R package and an FDR threshold of 0.5. Functional enrichment analysis has been performed using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) -

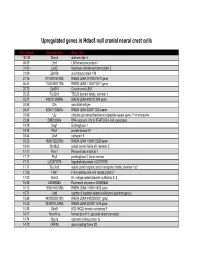

Supp Table 1.Pdf

Upregulated genes in Hdac8 null cranial neural crest cells fold change Gene Symbol Gene Title 134.39 Stmn4 stathmin-like 4 46.05 Lhx1 LIM homeobox protein 1 31.45 Lect2 leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 31.09 Zfp108 zinc finger protein 108 27.74 0710007G10Rik RIKEN cDNA 0710007G10 gene 26.31 1700019O17Rik RIKEN cDNA 1700019O17 gene 25.72 Cyb561 Cytochrome b-561 25.35 Tsc22d1 TSC22 domain family, member 1 25.27 4921513I08Rik RIKEN cDNA 4921513I08 gene 24.58 Ofa oncofetal antigen 24.47 B230112I24Rik RIKEN cDNA B230112I24 gene 23.86 Uty ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y chromosome 22.84 D8Ertd268e DNA segment, Chr 8, ERATO Doi 268, expressed 19.78 Dag1 Dystroglycan 1 19.74 Pkn1 protein kinase N1 18.64 Cts8 cathepsin 8 18.23 1500012D20Rik RIKEN cDNA 1500012D20 gene 18.09 Slc43a2 solute carrier family 43, member 2 17.17 Pcm1 Pericentriolar material 1 17.17 Prg2 proteoglycan 2, bone marrow 17.11 LOC671579 hypothetical protein LOC671579 17.11 Slco1a5 solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 17.02 Fbxl7 F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 7 17.02 Kcns2 K+ voltage-gated channel, subfamily S, 2 16.93 AW493845 Expressed sequence AW493845 16.12 1600014K23Rik RIKEN cDNA 1600014K23 gene 15.71 Cst8 cystatin 8 (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) 15.68 4922502D21Rik RIKEN cDNA 4922502D21 gene 15.32 2810011L19Rik RIKEN cDNA 2810011L19 gene 15.08 Btbd9 BTB (POZ) domain containing 9 14.77 Hoxa11os homeo box A11, opposite strand transcript 14.74 Obp1a odorant binding protein Ia 14.72 ORF28 open reading -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

G PROTEIN-COUPLED RECEPTORS Overview:- The completion of the Human Genome Project allowed the identification of a large family of proteins with a common motif of seven groups of 20-24 hydrophobic amino acids arranged as α-helices. Approximately 800 of these seven transmembrane (7TM) receptors have been identified of which over 300 are non-olfactory receptors (see Frederikson et al., 2003; Lagerstrom and Schioth, 2008). Subdivision on the basis of sequence homology allows the definition of rhodopsin, secretin, adhesion, glutamate and Frizzled receptor families. NC-IUPHAR recognizes Classes A, B, and C, which equate to the rhodopsin, secretin, and glutamate receptor families. The nomenclature of 7TM receptors is commonly used interchangeably with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), although the former nomenclature recognises signalling of 7TM receptors through pathways not involving G proteins. For example, adiponectin and membrane progestin receptors have some sequence homology to 7TM receptors but signal independently of G-proteins and appear to reside in membranes in an inverted fashion compared to conventional GPCR. Additionally, the NPR-C natriuretic peptide receptor has a single transmembrane domain structure, but appears to couple to G proteins to generate cellular responses. The 300+ non-olfactory GPCR are the targets for the majority of drugs in clinical usage (Overington et al., 2006), although only a minority of these receptors are exploited therapeutically. Signalling through GPCR is enacted by the activation of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins), made up of α, β and γ subunits, where the α and βγ subunits are responsible for signalling. The α subunit (tabulated below) allows definition of one series of signalling cascades and allows grouping of GPCRs to suggest common cellular, tissue and behavioural responses. -

Identification of Potential Key Genes and Pathway Linked with Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Based on Integrated Bioinformatics Analyses

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.20248688; this version posted December 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of potential key genes and pathway linked with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on integrated bioinformatics analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 , Iranna Kotturshetti 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. 3. Department of Ayurveda, Rajiv Gandhi Education Society`s Ayurvedic Medical College, Ron, Karnataka 562209, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.20248688; this version posted December 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) is neurodegenerative disease also called prion disease linked with poor prognosis. The aim of the current study was to illuminate the underlying molecular mechanisms of sCJD. The mRNA microarray dataset GSE124571 was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened. -

Anti-GNB4 (GW21993)

3050 Spruce Street, Saint Louis, MO 63103 USA Tel: (800) 521-8956 (314) 771-5765 Fax: (800) 325-5052 (314) 771-5757 email: [email protected] Product Information Anti-GNB4 antibody produced in chicken, affinity isolated antibody Catalog Number GW21993 Formerly listed as GenWay Catalog Number 15-288-21993, Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta 4 Anti- body. The product is a clear, colorless solution in phosphate – Storage Temperature Store at 20 °C buffered saline, pH 7.2, containing 0.02% sodium azide. Synonyms: Guanine nucleotide-binding protein, beta-4 Species Reactivity: Human, mouse subunit, Transducin beta chain 4 Tested Applications: WB Product Description Recommended Dilutions: Recommended starting dilution Guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins) are for Western blot analysis is 1:500, for tissue or cell staining involved as a modulator or transducer in various trans- 1:200. membrane signaling systems. The beta and gamma chains are required for the GTPase activity. for replacement of GDP Note: Optimal concentrations and conditions for each by GTP. and for G protein-effector interaction. application should be determined by the user. NCBI Accession number: NP_067642.1 Precautions and Disclaimer Swiss Prot Accession number: Q9HAV0 This product is for R&D use only, not for drug, household, or other uses. Due to the sodium azide content a material Gene Information: Human .. GNB4 (59345) safety data sheet (MSDS) for this product has been sent to Immunogen: Recombinant protein Guanine nucleotide- the attention of the safety officer of your institution. Please binding protein, beta-4 subunit consult the Material Safety Data Sheet for information regarding hazards and safe handling practices. -

Identifying Genes in Monoamine Nuclei That May Determine Stress Vulnerability and Depressive Behavior in Wistar–Kyoto Rats

Neuropsychopharmacology (2006) 31, 2449–2461 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0893-133X/06 $30.00 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Identifying Genes in Monoamine Nuclei that may Determine Stress Vulnerability and Depressive Behavior in Wistar–Kyoto Rats 1 2 2 ,1 Kimberly A Pearson , Alisson Stephen , Sheryl G Beck and Rita J Valentino* 1Department of Pediatrics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 2Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA The Wistar–Kyoto (WKY) rat is stress sensitive and exhibits depressive-like behavior. The locus coeruleus (LC)–norepinephrine and dorsal raphe (DR)–serotonin systems mediate certain aspects of the stress response and have been implicated in depression. Microarray technology was used to identify gene expression differences in the LC and DR between WKY vs Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats that might account for the WKY phenotype. RNA was isolated from microdissected LC and DR, amplified, and hybridized to microarrays (1 array/ subject, n ¼ 4/group). Significance of microarray (SAM) analysis revealed increased expression of 66 genes in the LC and 19 genes in the DR and decreased expression of 33 genes in the DR of WKY rats. Hierarchical clustering identified differences in gene expression profiles of WKY vs SD rats that generally concurred with SAM. Notably, genes that encoded for enzymes involved in norepinephrine turnover, amino-acid receptors, and certain G-protein-coupled receptors were elevated in the LC of WKY rats. The DR of WKY rats showed decreased expression of genes encoding several potassium channels and neurofilament genes. The chromosomal locations of 15 genes that were differentially expressed in WKY rats were near loci identified as contributing to depressive-like behaviors in the rat. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Cssls) Derived from Guangxi Wild Rice (Oryza Rufipogon Gri Ff.

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Development of Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines (CSSLs) Derived from Guangxi Wild Rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) under Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Background and the Identification of QTLs for Plant Architecture, Agronomic Traits and Cold Tolerance Ruizhi Yuan y, Neng Zhao y, Babar Usman y , Liang Luo, Shanyue Liao, Yufen Qin, Gul Nawaz and Rongbai Li * State Key Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agro-Bioresources, College of Agriculture, Guangxi University, Nanning 530004, China; [email protected] (R.Y.); [email protected] (N.Z.); [email protected] (B.U.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (Y.Q.); [email protected] (G.N.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +86-136-0009-4135 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 12 July 2020; Accepted: 21 August 2020; Published: 22 August 2020 Abstract: Common wild rice contains valuable resources of novel alleles for rice improvement. It is well known that genetic populations provide the basis for a wide range of genetic and genomic studies. In particular, chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) ais a powerful tool for fine mapping of quantitative traits, new gene discovery and marker-assisted breeding. In this study, 132 CSSLs were developed from a cultivated rice (Oryza sativa) cultivar (93-11) and common wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff. DP30) by selfing-crossing, backcrossing and marker-assisted selection (MAS). Based on the high-throughput sequencing of the 93-11 and DP30, 285 pairs of Insertion-deletions (InDel) markers were selected with an average distance of 1.23 Mb. -

Novel Methylation Patterns Predict Outcome in Uveal Melanoma

Article Novel Methylation Patterns Predict Outcome in Uveal Melanoma Sarah Tadhg Ferrier 1 and Julia Valdemarin Burnier 1,2,3,* 1 Cancer Research Program, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada, H4A 3J1; [email protected] 2 Experimental Pathology Unit, Department of Pathology, McGill University; Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 0G4 3 Department of Oncology, McGill University; Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 0G4 * Correspondence: [email protected] Table S1. Differentially methylated genes in the Pathways in Cancer KEGG pathway with a log FC ≥ 1.5. Average Average Log Fold Change Differentially Adjusted P Beta Beta ID Gene Name Species (High vs Low Methylated Probes Value Value, Value, Risk) Low High ABL proto-oncogene 1, non- ABL1 Homo sapiens cg13440206, −1.85238 1.39E−06 0.576589 0.259088 receptor tyrosine kinase(ABL1) cg02915920 −1.84042 8.03E−06 0.482846 0.192714 cg21195763 1.685721 3.13E−19 0.573548 0.83358 ADCY2 adenylate cyclase 2(ADCY2) Homo sapiens cg14116052 2.454448 4.3E−24 0.513149 0.885217 ADCY6 adenylate cyclase 6(ADCY6) Homo sapiens cg25196508 3.480923 2.9E−25 0.188362 0.792499 AKT serine/threonine kinase AKT1 Homo sapiens cg14116052 2.454448 4.3E−24 0.513149 0.885217 1(AKT1) bone morphogenetic protein BMP4 Homo sapiens cg08046044 1.527233 3.98E−06 0.049923 0.209543 4(BMP4) cg01873886 1.789942 2.55E−05 0.026254 0.1723 Life 2020, 10, x; doi: FOR PEER REVIEW www.mdpi.com/journal/life Life 2020, 10, x FOR PEER REVIEW 2 of 22 cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1B Homo sapiens cg06197769