70 Riversdale Road Hawthorn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

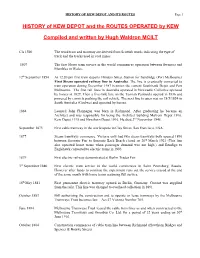

__History of Kew Depot and It's Routes

HISTORY OF KEW DEPOT AND ITS ROUTES Page 1 HISTORY of KEW DEPOT and the ROUTES OPERATED by KEW Compiled and written by Hugh Waldron MCILT CA 1500 The word tram and tramway are derived from Scottish words indicating the type of truck and the tracks used in coal mines. 1807 The first Horse tram service in the world commences operation between Swansea and Mumbles in Wales. 12th September 1854 At 12.20 pm first train departs Flinders Street Station for Sandridge (Port Melbourne) First Steam operated railway line in Australia. The line is eventually converted to tram operation during December 1987 between the current Southbank Depot and Port Melbourne. The first rail lines in Australia operated in Newcastle Collieries operated by horses in 1829. Then a five-mile line on the Tasman Peninsula opened in 1836 and powered by convicts pushing the rail vehicle. The next line to open was on 18/5/1854 in South Australia (Goolwa) and operated by horses. 1864 Leonard John Flannagan was born in Richmond. After graduating he became an Architect and was responsible for being the Architect building Malvern Depot 1910, Kew Depot 1915 and Hawthorn Depot 1916. He died 2nd November 1945. September 1873 First cable tramway in the world opens in Clay Street, San Francisco, USA. 1877 Steam tramways commence. Victoria only had two steam tramways both opened 1890 between Sorrento Pier to Sorrento Back Beach closed on 20th March 1921 (This line also operated horse trams when passenger demand was not high.) and Bendigo to Eaglehawk converted to electric trams in 1903. -

Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Acts 1890 and 1893

VICTORIA. ANNO SEXAGESIMO PEIMO VICTOKLE BEGINS ####*####*#**#*######****^ No. 1491. An Act to amend the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Acts 1890 and 1893. [2Ath August, 1897.] T)E it enacted by the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty by and with -*-* the advice and consent of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly of Victoria in this present Parliament assembled ana by the authority of the same as follows (that is to say):— 1. (1) This Act may be cited as the Melbourne and Metropolitan short title ana con« Board of Works Act 1897, and shall be read as one with the Melbourne struction- and Metropolitan Board of Works Act 1890 (hereinafter called the N*08-1197'1351i Principal Act) and with the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Act 1893; and this Act and the said Acts may be cited together as the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works Acts. (2) Sections three four five six and seven of this Act shall be deemed to be a portion of Part III* of the Principal Act. 2. The Act mentioned in the First Schedule to this Act to the Repeal. extent mentioned therein shall be and the same is hereby repealed. First schedule. Such repeal shall not be deemed to affect any notices given or things commenced or done by the Board pursuant to any of the repealed enactments before the commencement of this Act. 3. In DM 25 61 VICT.] Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works. [No. 1491. Interpretation. 3. In section seventy-six of the Principal Act for the definitions of the words " sewer" and u street" respectively there shall be substituted the following definitions, and such substitutions shall be deemed to take effect as from the commencement of the Principal Act:— " Sewer." "Sewer" shall mean and include any sewer or underground gutter or channel which is not a drain within the meaning of this Part of this Act and any drain or portion of a drain laid between a sewer and the boundary line of any allotment or curtilage. -

Hawthorn Heritage Study

HAWTHORN HERITAGE STUDY APRIL 1993 The Hawthorn Heritage Study was one of the three Special Strategy Plan Projects started during 1991. The Heritage Study was prepared by a team led by Meredith Gould, Conservation Architect, with substantial input from the Townscape and Heritage Topic Group as part of the Hawthorn Strategy Plan process. Some sections of the study were completed in draft form as early as late 1991; other sections have only reached completion now. This Study is the first ever comprehensive assessment of Hawthorn's urban and landscape heritage. Every bUilding in Hawthorn has been assessed for its heritage value. Significant trees, parks, landscapes and roadways have also been evaluated and recorded. The heritage areas proposed in the Study were endorsed by Hawthorn Council for the purpose of public consultation on 10 December 1991. Comments were sought by means of a map and explanatory material in a Strategy Plan booklet letterboxed throughout Hawthorn in March 1991. On 25 August 1992, Council resolved that a proposed Planning Scheme Amendment be drafted to include: Heritage protection for areas Protection of individual buildings of stand alone and contributory signiticance outside heritage areas. Voluntary registration of other individual places outside heritage areas, for the purpose of heritage protection. A degree of heritage control substantially reduced compared to normal Urban Conservation Areas. Council on 20 April 1993 resolved to publish the completed study; to notify property owners of buildings recommended for inclusion on the Historic Buildings Register, the National Estate Register and the Significant Tree Register; and to refer for further officer investigation the recommendations on signiticant street trees, kerbs/gutterslfootpaths/roadways, laneways, drains and creeks, Yarra River/Gardiners Creek, parks/reserves, and the establishment of an internal monitoring system. -

Appendix 1 Citations for Proposed New Precinct Heritage Overlays

Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review Appendix 1 Citations for proposed new precinct heritage overlays © Biosis 2017 – Leaders in Ecology and Heritage Consulting 183 Southbank and Fishermans Bend Heritage Review A1.1 City Road industrial and warehouse precinct Place Name: City Road industrial and warehouse Heritage Overlay: HO precinct Address: City Road, Queens Bridge Street, Southbank Constructed: 1880s-1930s Heritage precinct overlay: Proposed Integrity: Good Heritage overlay(s): Proposed Condition: Good Proposed grading: Significant precinct Significance: Historic, Aesthetic, Social Thematic Victoria’s framework of historical 5.3 – Marketing and retailing, 5.2 – Developing a Context: themes manufacturing capacity City of Melbourne thematic 5.3 – Developing a large, city-based economy, 5.5 – Building a environmental history manufacturing industry History The south bank of the Yarra River developed as a shipping and commercial area from the 1840s, although only scattered buildings existed prior to the later 19th century. Queens Bridge Street (originally called Moray Street North, along with City Road, provided the main access into South and Port Melbourne from the city when the only bridges available for foot and wheel traffic were the Princes the Falls bridges. The Kearney map of 1855 shows land north of City Road (then Sandridge Road) as poorly-drained and avoided on account of its flood-prone nature. To the immediate south was Emerald Hill. The Port Melbourne railway crossed the river at The Falls and ran north of City Road. By the time of Commander Cox’s 1866 map, some industrial premises were located on the Yarra River bank and walking tracks connected them with the Sandridge Road and Emerald Hill. -

TROLLEY WIRE AUGUST 2006 TTRROOLLLLEEYY WWIIRREE AUSTRALIA’S TRAMWAY MUSEUM MAGAZINE AUGUST 2006 No

90814 National Advertising 15/8/06 3:00 PM Page 1 TTRROOLLLLEEYY No.306 WWIIRREE AUGUST 2006 Print Post Approved PP245358/00021 $8.80* In this issue • Victorian Railways Trams • Melbourne Opening Dates • Glenreagh Mountain Railway/Tramway 90814 National Advertising 18/8/06 10:00 AM Page 2 TROLLEY WIRE AUGUST 2006 TTRROOLLLLEEYY WWIIRREE AUSTRALIA’S TRAMWAY MUSEUM MAGAZINE AUGUST 2006 No. 306 Vol. 47 No. 3 - ISSN 0155-1264 CONTENTS MELBOURNE’S ELECTRIC TRAMWAY CENTENARY: VICTORIAN RAILWAYS TRAMS............................................3 MELBOURNE’S TRAMWAY SYSTEM: LIST OF OPENING DATES........................................................8 GLENREAGH MOUNTAIN RAILWAY/TRAMWAY............16 HERE AND THERE...................................................................20 MUSEUM NEWS.......................................................................25 Published by the South Pacific Electric Railway Co-operative Society Limited, PO Box 103, Sutherland, NSW 1499 Phone: (02) 9542 3646 Fax: (02) 9545 3390 Editor......................................................Bob Merchant Sub-editing and Production..........................Dale Budd Randall Wilson Ross Willson *Cover price $8.80 (incl. GST) Subscription Rates (for four issues per year) to expire A passenger’s view from Sydney O class car 1111 at in December. the Sydney Tramway Museum. Conductor Geoff Graham is chatting to the passengers on the return Australia .........................................................$A32.00 journey from the northern terminus to the Museum on New -

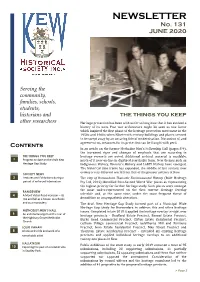

KHS June 2020 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER No. 131 JUNE 2020 Serving the community, families, schools, students, historians and the things you keep other researchers Heritage protection has been with us for so long now that it has evolved a history of its own. Post war architecture might be seen as one factor which inspired the first phase of the heritage protection movement in the 1950s and 1960s when Nineteenth century buildings and places seemed to be swept away by an uncaring tide of modernisation. Discussion of, and Contents agreement on, measures for its protection can be fraught with peril. In an article on the former Methodist Men’s Fellowship Hall (pages 8-9), the increased rigor and changes of emphasis that are occurring in THE THINGS YOU KEEP heritage research are noted. Additional archival material is available, 1 Progress to date on the draft Kew much of it now on-line in digitised searchable form. New themes such as Heritage Gap Study Indigenous History, Women’s History and LGBTI History have emerged. The historical time frame has expanded, the middle of last century now evokes a very different world from that of the pioneer settlers of Kew. SOCIETY NEWS 3 Lectures and Exhibitions during a The City of Boroondara Thematic Environmental History (Built Heritage period of enforced hibernation Pty Ltd, 2012) identified Post-Second World War places as representing the highest priority for further heritage study. Such places were amongst the most under-represented on the then current Heritage Overlay RANGEVIEW 4 A Mont Victor Road mansion – its schedule and, at the same time, under the most frequent threat of rise and fall as a house, as schools demolition or unsympathetic alteration. -

Heritage Citation

NAME OF HERITAGE PLACE: Chesney Wolde Address: 57 Berkeley Street, Hawthorn Name: Chesney Wolde Survey Date: 25 August 2020 Place Type: Residential Architect: Not Known Grading: Significant Builder: Not Known Extent of Overlay: To title boundaries Construction Date: c1916 Historical Context The First Nations People, the Wurundjeri, have a connection to the land along the valleys of the Yarra River and Gardiners Creek.1 This connection extends back thousands of years, and continues today. The boundaries of Hawthorn are defined by Barkers Road and Burke Road to the north and east; and two watercourses, the Yarra River and its tributary, Gardiners Creek.2 Of 1 Gary Presland, First People. The Eastern Kulin of Melbourne, Port Phillip and Central Victoria, p 25. 2 The former City of Hawthorn 1 the watercourses, hills, valleys and plains within the Melbourne region, it is the Yarra River that is its defining feature, and one that serves as its artery. It was its abundant supply of freshwater that saw European settlement establish along the Yarra River in the nineteenth century. Today the metropolis still obtains much of its water from the Yarra and its tributaries in the nearby ranges. It was a short distance from the subject site, that in 1836-37 pastoralist John Gardiner (1798-1878) settled with his family, and Joseph Hawdon and John Hepburn. They drove cattle overland from Sydney to the property they established on Gardiners Creek,3 land now occupied by Scotch College. Improved transport links with the city, initially the completion of the railway from the city to Hawthorn in 1861, stimulated residential development. -

Melbourne-Metropolitan-Tramways-Board-Building- 616-Little-Collins-Street-Melbourne

Melbourne Metropolitan Tramway Study Gary Vines 2011 List of surviving heritage places Contents Horse Tramways ...................................................................................................... 2 Cable Tram engine houses..................................................................................... 2 Cable Tram car sheds ............................................................................................. 6 Electric Tram Depots .............................................................................................. 8 Waiting Shelters ...................................................................................................... 12 Substations .............................................................................................................. 20 Overhead and electricity supply ............................................................................ 24 Sidings and trackwork ............................................................................................ 26 Bridges ..................................................................................................................... 29 Workshops ............................................................................................................... 32 Offices ...................................................................................................................... 32 Recreation buildings ............................................................................................... 33 Accommodation -

SCG Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation

Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation September 2019 spence-consulting.com Spence Consulting 2 Analysis of Victorian Councils Post Amalgamation Analysis by Gavin Mahoney, September 2019 It’s been over 20 years since the historic Victorian Council amalgamations that saw the sacking of 1600 elected Councillors, the elimination of 210 Councils and the creation of 78 new Councils through an amalgamation process with each new entity being governed by State appointed Commissioners. The Borough of Queenscliffe went through the process unchanged and the Rural City of Benalla and the Shire of Mansfield after initially being amalgamated into the Shire of Delatite came into existence in 2002. A new City of Sunbury was proposed to be created from part of the City of Hume after the 2016 Council elections, but this was abandoned by the Victorian Government in October 2015. The amalgamation process and in particular the sacking of a democratically elected Council was referred to by some as revolutionary whilst regarded as a massacre by others. On the sacking of the Melbourne City Council, Cr Tim Costello, Mayor of St Kilda in 1993 said “ I personally think it’s a drastic and savage thing to sack a democratically elected Council. Before any such move is undertaken, there should be questions asked of what the real point of sacking them is”. Whilst Cr Liana Thompson Mayor of Port Melbourne at the time logically observed that “As an immutable principle, local government should be democratic like other forms of government and, therefore the State Government should not be able to dismiss any local Council without a ratepayers’ referendum. -

Hawthorn Bridge Bridge Road, Yarra River, Richmond Significance

City ofYarra Heritage Review: Building Citations Building: Hawthorn Bridge Significance: A Address: Bridge Road, Yarra River, Melway Map Ref: 2H E7 Richmond Building Type: Road Bridge Construction Date: 1861 Architect: Unknown Builder: Unknown Intactness: Condition: G[ ] F[x] P[ G[x] F[ ] P[ Existing Heritage Listings: Recommended Heritage Listings: Victorian Heritage Register [ ] Victorian Heritage Register [x] Register of the National Estate [x] Register of the National Estate [x] National Trust [ ] Heritage Overlay Controls [x] AI lorn Lovell & Associates 37 City of Yarra Heritage Review: Building Citations History The Hawthorn Bridge was opened in November 1861 and it is the oldest existing metal truss bridge in Australia. The next oldest surviving metal truss bridges are at Gundagai, New South Wales (1867; 31.4m maximum span), Redesdale, Victoria (1868; 45.7m) and the Denison Bridge at Bathurst, New South Wales (1870, 34.5m). The maximum span of the Hawthorn Bridge was exceeded by the Longford Rail Bridge, Tasmania, in 1871 (64.0m).1 The cable tram service was established along Bridge Road in 1885. When the route was electrified in 1916, the present ornamental tram-wire supports were erected on the bridge by the then Hawthorn Tramways Trust. The supports were erected independently of the bridge, and are not incorporated into its structure.2 Description The Hawthorn Bridge is triple-span box-girder bridge over the Yarra River, connecting Richmond and Hawthorn. The four-lane road deck rests on four deck-type lattice trusses at 4.3m centres. The trusses are simply supported, with spans of 21.3m, 45.7m and 21.3m. -

Amendment C333boro

AMENDMENT C333BORO System Note: The following ordinance will be modified in Clause:22 LOCAL PLANNING POLICIES, Sub-Clause:22.03 HERITAGE POLICY 22.03-7 Reference documents C333boro Assessment of Heritage Precincts in Kew (City of Boroondara, April 2013) Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn (City of Boroondara, August 2008, updated March 2012) Auburn Village Heritage Study (City of Boroondara, 2005) Balwyn Road Residential Precinct, Canterbury: Stage 2 Heritage Precinct Review (City of Boroondara, August 2006) Boroondara Heritage Property Database Boroondara Schedule of Gradings Map Camberwell Conservation Study (City of Camberwell, 1991) Camberwell Junction Heritage Review (City of Boroondara, 2008, updated 2013) Canterbury Hill Estate Precinct Citation (2014) City Of Boroondara Municipal-Wide Heritage Gap Study Volume 1: Canterbury (Context Pty Ltd, 25 May 2017) City Of Boroondara Municipal-Wide Heritage Gap Study Volume 2: Camberwell (Context Pty Ltd, 26 September 2017) City Of Boroondara Municipal-Wide Heritage Gap Study Volume 7: Glen Iris (Context Pty Ltd, 15 October 2020) City of Kew Urban Conservation Study (City of Kew, 1988) Creswick Estate Precinct Heritage Citation (2016) Fairmount Park Estate Precinct Heritage Citation (2016) Grange Avenue Residential Precinct Citation (August 2014) Hawthorn Heritage Precincts Study (City of Boroondara, April 2012) Hawthorn Heritage Study (City of Hawthorn, 1993) Heritage Policy - Statements of Significance (City of Boroondara, August 2016, or as amended and adopted by Council from time to time) Kew and Hawthorn Further Investigations - Assessment of Specific Sites (February 2014) Kew Junction Commercial Heritage Study (September 2013) National Trust of Australia (Victoria) Technical Bulletin 8.1 Fences & Gates (1988) Review of B-graded Buildings in Kew, Camberwell and Hawthorn (City of Boroondara, January 2007, updated June 2007 and November 2009) Volumes 1, 2 and 3. -

A Short History of Our Club

A Short History of our club. The Beginning In the early 1950’s, Australia was a vastly different place. Its population of a little over 12 million was almost exclusively of British descent. It had just emerged from almost six years of World War II during which hundreds of thousands of its men and women enlisted voluntarily for service in the armed forces. By 1949 Australia was emerging from wartime shortages and rationing. Oil exploration had not started. Mining was a very unsophisticated affair and the pick and shovel were the order of the day. Jet aircraft had not invaded the skies. High rise building was confined to St Patrick’s spire on Eastern Hill. We only just had our first Australian car. We had no freeways but the roads were not choked as few people had cars. Having children was normal; marrying beforehand was usual. Rotary had expanded from its beginnings in Chicago with clubs being formed in Canada, Ireland and England. Early in the second decade of the century we had a new organisation calling itself Rotary International. Two distinguished Canadians were appointed by RI in 1921 to undertake the task of establishing Rotary in Australia. Almost by accident, Melbourne was the site of that first club when Sydney passed up a prior opportunity. It is interesting to note that it took 16 years for Rotary to expand from Chicago to Melbourne (some 14,000km), it took another 32 years for it to expand a further 7km to Hawthorn. Between its formation in 1921 and the start of WWII, the Melbourne club ceded territory for only 3 other clubs to be formed, Essendon, Dandenong and Footscray.