D:\Tul\Mizo Studies April-June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule for Selection of Below Poverty Line (Bpl) Families

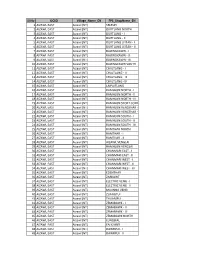

SCHEDULE-I: SCHEDULE FOR SELECTION OF BELOW POVERTY LINE (BPL) FAMILIES STATE & STATE CODE : MIZORAM 15 NAME OF DISTRICT : CHAMPHAI DISTRICT CODE : 04 NAME OF BLOCK : NGOPA BLOCK CODE : 03 In Thlakhat awmdan Chhungkaw a ST/ Bank RUS Nu/ Village/ Village/ (katcha/ Voter ID Ration hotu chawhruala SC/ Account NO Pa hming Veng Veng Code No semi Card No Card No House in luah# hming pawisa nei/miIn Others No Chhungkaw pucca/ member zat lakluh zat pucca)@ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1967 Thangliana Khuala (L) 5 1700 Changzawl 10 22 01 11 FDV0198457 10097 ST 97009514505 1968 Lalzamlova Thanliana (L) 3 1700 Changzawl 10 24 01 11 FDV0219915 10068 ST 97000951035 1969 K Lalbiaksanga Lalbiaknunga (L) 2 1700 Changzawl 10 70 01 11 SSZ0022897 10019 ST 97003297000 1970 Lalnunhlima K Zabuanga (L) 7 3500 Changzawl 10 71 01 11 FDV0044826 10046 ST 25034017704 1971 Lalchhanhima Lalduhawma 5 2000 Changzawl 10 72 01 11 FDV0045047 10028 ST 97002524591 1972 Laldanga Ralkapa (L) 2 1700 Changzawl 10 75 01 11 FDV0049297 10030 ST 97002159377 1973 Hrangkima Tlanglawma (L) 6 2000 Changzawl 10 16 01 11 FDV0045039 10011 ST 97003793802 1974 Biakthangsanga Lalchhana 4 3000 Changzawl 10 80 01 11 FDV0062950 10003 ST 25034016438 1975 Lalsawmzuala Sapkhuma 1 2000 Changzawl 10 29 01 10 FDV0044545 10057 ST 97004199294 1976 Lalhmangaiha KT Hranga (L) 1 1500 Changzawl 10 60 01 11 FDV0044776 10034 ST 97004232030 1977 Sapkhuma Vanlalliana (L) 5 1700 Changzawl 10 7 01 11 FDV0045161 10093 ST 25034019553 1978 C Kapmawia Tlanglawma (L) 4 2500 Changzawl 10 16 01 11 FDV0044479 10104 -

The Mizoram.Gazette Publlshed by Autijority , /L " ' Vol

~c1. No. NB 907 ,The Mizoram.Gazette Publlshed by AutIJority , /l " ' Vol. XIX Aizawl Friday 30.1 U990 Agrahayana 9 S.B. 1912 Is!ue No, 48 h, Government of Mlzoram:;, , . -. " PART I') .. 1'~"O"lll!Jents.Postincs. Transfers, Powers. Leave and other. - " Personal Notices and Orders. ,;.* ., NOTIFICATION \ No.A.il20lil/l/90-P.!JRS(1l),u the 21st November.. 1990. In pursuance of Govt. of . hldial Ministry of'.Home Affairs Order No. 14020/55/90-UTS dt. 12. II. 90 or ,.., derin~ transfer/posting in respect of lAS officers: of AGMU Cadre. the Governor of Mizoram in the interest of Public service, is pleased to relieve Pu T.T. Joseph, lAS. (AGMU : 68). Financial Commissioner. Mizoram with effect from the date of handing over :,charge. , ., H. Lal Thlarnuana, Special Secretary to the Govt, of Mizoram, " !!, ,- f; ;, " ., -, .., No.A.19015/19!S9-PAR(R). the 26th November. 1990.•. The Governor of Mizoram J,s pl\'il:sed,to saaction 17 days Earned Leave with effect from 14.11.90 to 30.11.90 ta..Pi K. Lalkimi, -Supdt, Harne Department on private ground under the c.C.S (Leave) Rules, 1972 as amended from time to time. l,Certified, that the ,OlIjcei would have continued to hold the post of Superin- ,l4ndent J;>Ul for lIOI proceeding on leave. 3. Certified that the Officer would have continued to hold the same post and place from where she proceeded on leave and is authorised to draw during leave period the pay and allowances as admissible under the Rules. ..:r,··-l ' "- J;tq;$,\:J90IM84/8$"P~~).{th~ 29th November., IJ90. -

The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ·ORDINARY Published by Authority REGN. NO. N.E.-313 (MZ) Rs. 2/- per Issue VOL. XXX" Aizawl. Wednesday, 26.4.2006, Valsakha 6, S.E. 1928, Issue No. 103 NOTfCATION No. B. 14016/3/02-LAD/VC, the 18th April, 2006. In exercise of the powers co nferred by Section 7(1 )(2), Section 15 and Section 22(1) of the Lusbai Hills District (Village Councils) Act, 1953, as amended from time to time, the Gover- nor of Mizoram is pleased to approve Executive Body of the following Village Councils as shown in the enclosed Annexure within Cha mphai District. R. Sangliankhuma, Addl. Secretary, Local Administration Department. ANNEXURE CHAMPHAI DISTRICT -........------;-------- ----- 1 2 3 4 I4-KHAWBUNG Ale 1. Buang 1. Tinlinga· President 2. Thangchhinga Vice President & Treasurer 3. K. Lalzawngliana Secretary 4. ParlaV\oma Crier Ex-103/20C6 2 1 2 3 4 2. Bungzung J. Lalringzuala President 2. Lalpianfa Vice Pr�sider.t 3. La]zapa Trt:asurer 4. Lalhmingliana Secretary 5. Sangkhuma Crier 3. Bulfekzawl 1. Vanlalrin ga President 2. Chhunkhuma Vice Presifient 3. Chh un tb angvunga Treasurer 4. Laltums2nga Seer etary 5. I. F. }.'Iallga Crier 4. Chawngtui -E' Not yet formed Executive Body 5. Dungtlang 1. H. Laldin gliana President ., .. C. Zalawma Vice President 3. K. LaIthlamuana Treasurer 4. C. Lalzama Secretary 5. Kaprothanga Crier l 6. Farkawn 1. Lalslama President 2. Manghupa Vice President 3. Engm av. ia Treasurer 4. Ljansailova Secretary 5. Lalrawna Crier 7. Hruaikawn 1. C. Hranghleikapa President 2. Sangtinkulha Vice President 3. Sa ngtha n gpuia Treasurer 4 . -

Mizoram Education (Transfer and Posting of School Teachers) Rules

The Mizoral111~Gazette~' EXTRA ORDINARY, ' ' •.. ,- '. ,I Published by Authoritv' REGN. NO. N.E.-313 (MZ) Rs. 2/- per Issue Vol. XXXV Aizawl, W~dnesday, 26.4.2006, Vaihsakha 6, S.E. 1928, Issue No. 104 No .A. 23022/5/2006 EDN, the 12th April, 2006. In exercise of th,e power con• erred by clause (xxxv) of sub-section (2) of sectidh 30 of the Mizoram Educa• tion Act, 2e03 (Act No. 5 of .2003), the Governor of Mizoram" is pleased to make the [allowing rules, namely :- . 1. SnORT TITLE? EXTENT AND COMMENCEMENT : (1) These Rules may be called the Mizoram Education (Transfer and . Posting of School Teachers) Rules, 2006, (2) It shall extend to the whole of Mizoram in respect of Elementary ,Educdtion and Secondary£ducation, except Chakllla Autonomous District, Lai Autonomou3 District and Mara Autohomous Dis• trict in respect of Elementary Education 'only. (3) These rul es shall com::: into force from til~ date of notificati on in the Mizoram Gazette. 2. IN THESE RULES, UNLESS THE CONTEXT OTHERWISE REQUIRES : ;- (1')' "Act" means MizoramEducati~n Act, 2003 (Act No. 5 of 2003) (2) ""Appropriate AuthoJity" shall mean the authority.as specified in Rule 9; (3) "District" means the jurisdiction area prescribed by tb.e Government of District Education Officer; (4) "Elementary School" means Primary Schools and Middle Schools~ (5) "Government" means the Government of Mizoram. (€i) "Sanctioned strellgth'>"me'<lDSth.t' number of posts 'of teachers as a 'particular School as Sanctiolled by the Government., -', , (-7) "Schedule" m6anl~a Schedul~ appended .,to these Rule·s; -l"fl' Ex-l04/2006 2 (8) "Secondary School" means High Schools and Higher Secondary Schools. -

SELESIH 2 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl

Sl No DCSO Village_Name_EN FPS_ShopName_EN 1 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) SELESIH 2 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG NORTH 3 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG - I 4 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG - II 5 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG LEITAN - I 6 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) DURTLANG LEITAN - II 7 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - I 8 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - II 9 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN - III 10 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) BAWNGKAWN SOUTH 11 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - I 12 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - II 13 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG - III 14 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHALTLANG -IV 15 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) LAIPUITLANG 16 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - I 17 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - II 18 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN NORTH - III 19 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SPORT COMPLEX 20 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGTHAR - I 21 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGTHAR - II 22 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - I 23 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - II 24 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN SOUTH - III 25 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR NORTH 26 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR - I 27 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMTHAR - II 28 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) AIZAWL VENGLAI 29 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) RAMHLUN VENGLAI 30 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI EAST - I 31 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI EAST - II 32 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - I 33 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - II 34 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) CHANMARI WEST - III 35 AIZAWL EAST Aizawl (NT) EDENTHAR 36 AIZAWL -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX History and Historiography of Mizoram Mizo History Association September 2018 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor : Dr. Rohmingmawii The Editorial Board shall not be responsible for authenticity of data, results, views, and conclusions drawn by the contributors in this Journal. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX September 2018 Editor Dr. Rohmingmawii Editorial Board Dr. Lalngurliana Sailo Dr. Samuel Vanlalthlanga Dr. Malsawmliana Dr. H. Vanlalhruaia Lalzarzova Dr. Lalnunpuii Ralte MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2017 – 2019) President : Prof. Sangkima Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna (Rtd) Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati Govt. Hrangbana College Patron : Prof. Darchhawna Kulikawn, Aizawl Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga ............................... Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo ................. Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana .....................Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga ...................Govt. Aizawl West College Mr. -

Information on NADCP for FMD and Brucellosis

An information booklet on NADCP for FMD and Brucellosis Animal Husbandry & Veterinary Department, Government of Mizoram 1 2 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE NATIONAL STEERING COMMITTEE FOR NATIONAL ANIMAL DISEASE CONTROL PROGRAMME (NADCP) HELD UNDER CHAIRMANSHIP OF SECRETARY (AHD), DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & DAIRYING, MINISTRY OF FISHERIES, ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & DAIRYING ON 4 th October, 2019 AT KRISHI BHAWAN, NEW DELHI ___________________________________________________________________________ The first meeting of National Steering Committee for National Animal Disease Control Programme (NADCP) was held on 4 th October, 2019 under the Chairmanship of Secretary (AHD), Department of Animal Husbandry & Dairying Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry & Dairying. 2. The list of participants is placed at Annexure I. A video-conference was also held with States/ UTs who could not attend the meeting at Krishi Bhawan, New Delhi and the list of States are also mentioned in the Annexure. 3. At the outset, the Chairman welcomed the participants and gave the roadmap for implementation of National Animal Disease Control Programme for control of Foot & Mouth Disease (FMD) and Brucellosis (NADCP), which was launched by Hon’ble Prime Minister on 11th September, 2019. The Chairman emphasized on the enormity of the project that would require a tremendous, concerted and combined effort of the Centre and the States/ UTs to operationalize the programme at the ground-level so as to achieve its objectives. 4. Accordingly, the contours of the Operational Guidelines, the terms of reference/ role of a Programme Logistics Agency (PLA) and those of a Programme Management Agency (PMA) were discussed. The Chairman emphasized that PLA would be responsible for procurement, supply and distribution of the vaccines, ear tags and tag applicators thereby making them available to the State Governments (Animal Husbandry Department) at the district level maintaining the requisite cold- chain. -

State/Uts Code District Codecd Block Code Town/Village Code

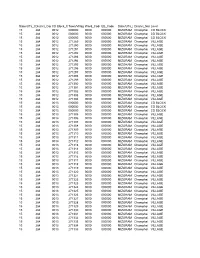

State/UTs_CodeDistrict_CodeCD Block_CodeTown/Village_CodeWard_Code EB_Code State/UTs_NameDistrict_NameLevel 15 284 0012 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0012 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0012 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0012 271289 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271290 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271291 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271292 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271293 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271294 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271295 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271296 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271297 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271298 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271299 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271300 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271301 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271302 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271303 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0012 271304 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0013 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0013 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0013 000000 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai CD BLOCK 15 284 0013 271305 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0013 271306 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0013 271307 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai VILLAGE 15 284 0013 271308 0000 000000 MIZORAM Champhai -

Statistical Hand Book Mizoram

STATISTICAL HAND BOOK MIZORAM 1985 N IEP A D C D06409 caChar (viAmpuB.. CH,-: fcix v j / •: " ’ < I-.. .V REFERENCES OISrtNCT HORS. DIST. BOUNDARY SUB DIV. b o u n d a r y BLOCK CENTRES SUB DIVISIONAL ROAD BLACKTOP h o s p it a l Copies 3,000 X)- 3 - t o - S I Department of Economics & Statistics Government of Mizoram ^Uzawl. Printed at the GOSEN PRESS, Aizawl, Mizoram. PREFACE This is the sixth issue of the Stat istical Hand Book published by the Directorate of Economics and Statis tics, Mizoram. Efforts are made to improve its cover age of data and to fill up the gaps of statistical infor mation as far as possible. The primary data presented in this book are most ly collected from various departments and the source of information is indicated at the top of each table. The data collected from various sources are scrutinised and compiled by Shri C. Lalparliana, Statistician and charts are prepared by Shri V.L. Ruata, Artist under the supervision of Shri Y. Chhetri, Research Officer. We gratefully acknowledge the co-operation exten ded to us by various departments in making available the materials for this publication. We hope Government departments and research scholars will make the best use of this publication. (F. THANGHULHA) Joint Director Economics and Statistics, & Add I. Chief Registrar of Births&Deaths, Mizoram (i) CONVERSION TABLES I-Standard of Weights 1 Ounce 28.350 grams 1 Pound 453/92 grams 1 Tola 11.664 grams 1 Chhatak 58.32 grams 1 Seer 933.10 grams I Maund 37.324 Kilograms 1 kilogram 2.205 Pounds 1.072 Seers 1 Ton 1016.05 Kilograms 1 Quintal 100 Kilograms I Metric tonne 220.462 Pound 10 Quintals Il^Standard of Length 1 Inch 25.4 Milimetres 1 foot 0.3048 metre 1 Metre 3.2808 feet 1 Yard 3 feet 0.9144 metre or 91.44 Centimetres 1 Mile 1.6093 Kilometres 1760 Yards 1 Kilometre 0.6214 Mile (ii) III-Standard of Capacity 1 Gallon 4.546 Litres 1 Litre 0.220 Gallon 1 Cubic foot 0.0283 Cubic nfietrc. -

1St Mizoram Finance Commission Report Mizo

CONTENT S Thuhma i-ii List of Annex iii List of Tables iv-vi Glossary vii-x Chapter – 1 A Khuhhawnna 1-12 Chapter – 2 Village Council-te Hnathawh Dan Kalphung 13-28 Bihchianna leh Ruahmanna Chapter – 3 Aizawl Municipal Council Hnathawh Dan 29-40 Kalphung Bihchianna leh Ruahmanna Chapter – 4 Autonomous District Council-te Hnathawh Dan 41-63 Kalphung Bihchianna leh Ruahmanna Chapter – 5 Mizoram Sum leh Pai Dinhmun 64-105 Chapter – 6 Village Council-te Sum leh Pai Dinhmun 106-126 Chapter – 7 Aizawl Municipal Council Sum leh Pai Dinhmun 127-141 Chapter – 8 Autonomous District Council-te Sum leh Pai 142-170 Dinhmun Chapter – 9 Sum leh Pai Inhlanchawn/Sem leh Indaihlohna 171-188 Phuhruk Dan Tur Chapter – 10 Terms of Reference-a Tul Dangte 189-202 Chapter – 11 Thil Pawimawh leh Kaihhnawih Dangte 203-220 Chapter – 12 Rawtna Hrang Hrang Khaikhawmna 221-250 Annex 251-365 THUHMA India Sawrkar hian tun hma atang tawhin thingtlang khua (Village) leh khawpui (Municipality) te inawp dan tihchangtlunna atan rawtna siamtu tur Committee/Commission te a lo din fo tawh a. Central Sawrkar Policy chu thlante (elected bodies) ngei thuam chaka Village leh Municipality-a thuneihna chan tir hi a ni. Chumi awmzia chu, Central Sawrkar chuan, thlante (elected bodies) hian sawrkar te zawk (mini government) anga hna an thawh theih nan, thuneihna semzai hi a duh a ni. 2. Mahse heng rawtna siam tam ber te hi sawrkar hnathawkte hian an kut atanga thuneihna pek chhuah chu uiin an dodala, bawhzuia tihhlawhtlin theih lohin an hup bet thin. 3. -

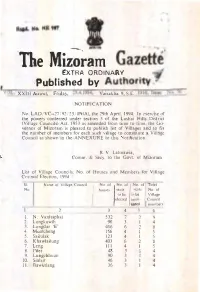

'The Mizoram £XTR.A

- , . ' , , -. 'The Mizoram £XTR.A. ORDINARY ,Published by Authority�' , O \' L. XXlll Aizawl, Friday, 29.4.1994, V.is.klla 9, S. E. 1916, issue No. 56_ NOTIFICATION No. LAD/VC--27/92/23/(Pt(Al, lhe 29th April. 1994. In exercise of the powers conferred under section 3 of the Lushai Hills DhstricL (Village Councils) Act, 1953 as amended from lime to time, the Go vernor of Mizoram is pleased to publish list of Villages and to fi)l'; the number of members for each suc-h village to constitute a ViJ1agc COlillcil as shown in the ANNEXURE to this otification. R. V. laimawia, COI1lIlf. & Secy. to the Govt. of Mizoram List of Village Councils. No. of Houses and Members for Village COllncil Election, 1994 51. Name of Village Council No. of No. of No. of TolAI No. hOuses seats seals No. of to be tn be Village I elecled InO\lli· Council nated members 2 --- 3 4 5 ---6 I. N. Vanlaiphai 532 7 2 9 2. Lungkawlh 90 3 I 4 3. Lungdar 'E' 416 6 2 8 4. Mualcheng 156 4 I 5 5. Sailulak 123 4 I 5 6. Khawlailung 403 6 2 8 7. Leng III 4 I 5 8. Piler 48 3 I 4 9. Lungchhu3n 90 3 I 4 10. Sialsir 46 3 I 4 II. Bawktlang 36 3 I 4 Ex-56/94 2 12. Khawbung South 327 5 2 7 13. BungzlIng 201 5 I (. 14. Zav.'lsei 66 3 I 4 15. Khuangthing 185 4 I :; 16. Buans .. 57 3 I 4 17. -

District Census Handbook, Aizawl, Part XIII-A & B, Series-31, Mizoram

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES-31 MIZORAM PARTS fXIIl A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT AIZA.WL DISTRICT P. LALNITHAJ'\GA of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations. Mizoram CONTENTS PAGES F0reword (iii) Preface (v) Map of the District (vii) Important Slatistics (ix) Analytical Note 1-23 (i) Ce,1suS concepts of rural and urban a\eas a~d other terms namely CensJs house, ho.;s~hold, Sc':leduled Ca~tes/Scheduled Tnbes, lIterates, main worker, marginal werker, non-worker etc, (ii) Brief History of the district and the Distri(;t Census HandboJk (iii) Scope of Village Directory, T 0wn Directory Statements and Primary Census Abstract (iv) Physical Asp("~ts !Iig\lights ~:m the chan&es in the juri:;diction of the d~strict during ,the decade includmg Its boundanes and any lmportant event on GeographIc or GeophysIcal aspect (v) Mijor cll1ract~ristic, of the district p:lrticularly in relation to the economic resources . namely forestry, minerals and mining, electricity and power, land and land-use pattern, tenancy, Agriculture, animal husbandry and veterinary service, fisheries, inclll~try, trade and commerce, transport etc. (vi) Major Social and Cultural events, natural and administrative developments and misce llaneous activities of note during thc decade (vii) Brief discription of places of religio·us, historical or archaeological importance in vil1ages and places of tourist interest in the bwns of the district {viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory and Primary Census