Parangiya, Kotte Giya (1964)…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clara E. Sipprell Papers

Clara E. Sipprell Papers An inventory of her papers at Syracuse University Finding aid created by: - Date: unknown Revision history: Jan 1984 additions, revised (ASD) 14 Oct 2006 converted to EAD (AMCon) Feb 2009 updated, reorganized (BMG) May 2009 updated 87-101 (MRC) 21 Sep 2017 updated after negative integration (SM) 9 May 2019 added unidentified and "House in Thetford, Vermont" (KD) extensively updated following NEDCC rehousing; Christensen 14 May 2021 correspondence added (MRC) Overview of the Collection Creator: Sipprell, Clara E. (Clara Estelle), 1885-1975. Title: Clara E. Sipprell Papers Dates: 1915-1970 Quantity: 93 linear ft. Abstract: Papers of the American photographer. Original photographs, arranged as character studies, landscapes, portraits, and still life studies. Correspondence (1929-1970), clippings, interviews, photographs of her. Portraits of Louis Adamic, Svetlana Allilueva, Van Wyck Brooks, Pearl S. Buck, Rudolf Bultmann, Charles E. Burchfield, Fyodor Chaliapin, Ralph Adams Cram, W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Einstein, Dorothy Canfield Fisher, Ralph E. Flanders, Michel Fokine, Robert Frost, Eva Hansl, Roy Harris, Granville Hicks, Malvina Hoffman, Langston Hughes, Robinson Jeffers, Louis Krasner, Serge Koussevitzky, Luigi Lucioni, Emil Ludwig, Edwin Markham, Isamu Noguchi, Maxfield Parrish, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dane Rudhyar, Ruth St. Denis, Otis Skinner, Ida Tarbell, Howard Thurman, Ridgely Torrence, Hendrik Van Loon, and others Language: English Repository: Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries 222 Waverly Avenue Syracuse, NY 13244-2010 http://scrc.syr.edu Biographical History Clara E. Sipprell (1885-1975) was a Canadian-American photographer known for her landscapes and portraits of famous actors, artists, writers and scientists. Sipprell was born in Ontario, Canada, a posthumous child with five brothers. -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon. -

Time Travelers Camporee a Compilation of Resources

1 Time Travelers Camporee A Compilation of Resources Scouts, Ventures, Leaders & Parents…. This is a rather large file (over 80 pages). We have included a “Table of Contents” page to let you know the page numbers of each topic for quick reference. The purpose of this resources to aid the patrols, crews (& adults) in their selection of “Patrol Time Period” Themes. There are numerous amounts of valuable information that can be used to pinpoint a period of time or a specific theme /subject matter (or individual).Of course, ideas are endless, but we just hope that your unit can benefit from the resources below…… This file also goes along with the “Time Traveler” theme as it gives you all a look into a wide variety of subjects, people throughout history. The Scouts & Ventures could possibly use some of this information while working on some of their Think Tank entries. There are more events/topics that are not covered than covered in this file. However, due to time constraints & well, we had to get busy on the actual Camporee planning itself, we weren’t able to cover every event during time. Who knows ? You might just learn a thing or two ! 2 TIME TRAVELERS CAMPOREE PATROL & VENTURE CREW TIME PERIOD SELECTION “RESOURCES” Page Contents 4 Chronological Timeline of A Short History of Earth 5-17 World Timeline (1492- Present) 18 Pre-Historic Times 18 Fall of the Roman Empire/ Fall of Rome 18 Middle Ages (5th-15th Century) 19 The Renaissance (14-17th Century) 19 Industrial Revolution (1760-1820/1840) 19 The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) 19 Rocky Mountain Rendezvous (1825-1840) 20 American Civil War (1861-1865) 20 The Great Depression (1929-1939) 20 History of Scouting Timeline 20-23 World Scouting (Feb. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 048, No 37, 5/3/1946 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1946 The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 5-3-1946 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 048, No 37, 5/3/1946 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1946 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 048, No 37, 5/3/1946." 48, 37 (1946). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1946/14 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1946 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I l --, NEW: ME:x:tCO LOBO Friday Apr1l 26, 1946 U. of Arizona I-I ere For Tvio Ball Game~ • In the • ~----------~---------~----~~--~--2-----------------~------- • • ng to take on all comers m the should be an mdlcation as to how well they fare the ;Bqrder NI:W MI:XICO LOBO handbllll dou,bles Will m Lobo Lair Confel'Cnce chp.mpionahl)HJ to be lntramurals A softball tound robin tourna Play Under Lights ment w1ll be played later 01 in held at Tucson May 10 and 11 Coach Woody Clements an Weekly Publication of the Associated Students of the Un1vers1ty of Hew Mexico the 13emester and orgamzat1ons are Apptoxtmately 20 men will JII~ke nounced th1s week plans for vol urged to get a team together now JIM M;ORAN lQyball and handball tpurnaments the h tp to the lnst tute Several At Tingley ~ield and subm1t thetr hst to Coach men have shown up well 1n ptac Vol XLVIII No 36 There -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Between Music

Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress 7 Rūta Stanevičiūtė Nick Zangwill Rima Povilionienė Editors Of Essence and Context Between Music and Philosophy Numanities - Arts and Humanities in Progress Volume 7 Series Editor Dario Martinelli, Faculty of Creative Industries, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Vilnius, Lithuania [email protected] The series originates from the need to create a more proactive platform in the form of monographs and edited volumes in thematic collections, to discuss the current crisis of the humanities and its possible solutions, in a spirit that should be both critical and self-critical. “Numanities” (New Humanities) aim to unify the various approaches and potentials of the humanities in the context, dynamics and problems of current societies, and in the attempt to overcome the crisis. The series is intended to target an academic audience interested in the following areas: – Traditional fields of humanities whose research paths are focused on issues of current concern; – New fields of humanities emerged to meet the demands of societal changes; – Multi/Inter/Cross/Transdisciplinary dialogues between humanities and social and/or natural sciences; – Humanities “in disguise”, that is, those fields (currently belonging to other spheres), that remain rooted in a humanistic vision of the world; – Forms of investigations and reflections, in which the humanities monitor and critically assess their scientific status and social condition; – Forms of research animated by creative and innovative humanities-based -

Oral History Interview with Robert M. Light, 2008 Apr. 25

Oral history interview with Robert M. Light, 2008 Apr. 25 Funding for this interview was provided by Art Dealers Association of America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Robert Light on 2008 April 25. The interview took place at Light's office in Monticeto, California, and was conducted by Gail Aronow for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Funding for this interview was provided by a grant from the Art Dealers Association of America. Gail Aronow has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview GAIL ARONOW: This is Gail Aronow interviewing Robert Light at his office at 1224 Coast Village Circle in Montecito, California, on April 25, 2008, for the Archives of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution. This is disc number one. Mr. Light, hello. ROBERT M. LIGHT: Hello. MS. ARONOW: Would you care to talk about where you were born and when, and your early childhood, your parents, your education? MR. LIGHT: All right. A rather brief overview of the unimportant parts of my life: I was born in 1929 and grew up in Fairfield County in Connecticut. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9325552 The Ray Bradbury Theater: A case study of the adaptation process from the written artifact to the cinematic text McConnell, Mary Beth Petrasik, Ph.D. -

SBI PO Mains Capsule

SBI PO Mains Capsule www.BankExamsToday.Com SBI PO Mains Capsule Table of Contents Current Affairs: January ............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Current Affairs: February ........................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Current Affairs: March ............................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Current Affairs: April ............................................................................................................................................................................... 14 First in Banks: Banking History ................................................................................................................................................................. 23 Latest List of Indian banks - Their Heads and Head Office (April 2017) ................................................................................................... 24 List of Important Mergers of Banks in India............................................................................................................................................. 25 Full Forms of Bank Names ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Universe Contents 3 HD 149026 B

History . 64 Antarctica . 136 Utopia Planitia . 209 Umbriel . 286 Comets . 338 In Popular Culture . 66 Great Barrier Reef . 138 Vastitas Borealis . 210 Oberon . 287 Borrelly . 340 The Amazon Rainforest . 140 Titania . 288 C/1861 G1 Thatcher . 341 Universe Mercury . 68 Ngorongoro Conservation Jupiter . 212 Shepherd Moons . 289 Churyamov- Orientation . 72 Area . 142 Orientation . 216 Gerasimenko . 342 Contents Magnetosphere . 73 Great Wall of China . 144 Atmosphere . .217 Neptune . 290 Hale-Bopp . 343 History . 74 History . 218 Orientation . 294 y Halle . 344 BepiColombo Mission . 76 The Moon . 146 Great Red Spot . 222 Magnetosphere . 295 Hartley 2 . 345 In Popular Culture . 77 Orientation . 150 Ring System . 224 History . 296 ONIS . 346 Caloris Planitia . 79 History . 152 Surface . 225 In Popular Culture . 299 ’Oumuamua . 347 In Popular Culture . 156 Shoemaker-Levy 9 . 348 Foreword . 6 Pantheon Fossae . 80 Clouds . 226 Surface/Atmosphere 301 Raditladi Basin . 81 Apollo 11 . 158 Oceans . 227 s Ring . 302 Swift-Tuttle . 349 Orbital Gateway . 160 Tempel 1 . 350 Introduction to the Rachmaninoff Crater . 82 Magnetosphere . 228 Proteus . 303 Universe . 8 Caloris Montes . 83 Lunar Eclipses . .161 Juno Mission . 230 Triton . 304 Tempel-Tuttle . 351 Scale of the Universe . 10 Sea of Tranquility . 163 Io . 232 Nereid . 306 Wild 2 . 352 Modern Observing Venus . 84 South Pole-Aitken Europa . 234 Other Moons . 308 Crater . 164 Methods . .12 Orientation . 88 Ganymede . 236 Oort Cloud . 353 Copernicus Crater . 165 Today’s Telescopes . 14. Atmosphere . 90 Callisto . 238 Non-Planetary Solar System Montes Apenninus . 166 How to Use This Book 16 History . 91 Objects . 310 Exoplanets . 354 Oceanus Procellarum .167 Naming Conventions . 18 In Popular Culture . -

IAU Mercurian Nomenclature

Appendix 1 IAU Mercurian Nomenclature 1. IAU Nomenclature Rules Since its inception in Brussels in 1919 [1], the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has gradually developed a planetary nomenclature system that has evolved from a purely classically based system into a quite so- phisticated attempt to broaden the cultural base of the names approved for planetary bodies and surface features. At present, name selection is guided by 11 rules (quoted verbatim below) in addition to conventions decided upon by nomenclature task groups for individual Solar System bodies. The general rules are as follows1: 1. Nomenclature is a tool and the first consideration should be to make it simple, clear, and unambiguous. 2. In general, official names will not be given to features whose longest di- mensions are less than 100 metres, although exceptions may be made for smaller features having exceptional scientific interest. 3. The number of names chosen for each body should be kept to a minimum. Features should be named only when they have special scientific inter- est, and when the naming of such features is useful to the scientific and cartographic communities at large. 4. Duplication of the same surface feature name on two or more bodies, and of the same name for satellites and minor planets, is discouraged. Duplications may be allowed when names are especially appropriate and the chances for confusion are very small. 5. Individual names chosen for each body should be expressed in the language of origin. Transliteration for various alphabets should be given, but there will be no translation from one language to another. -

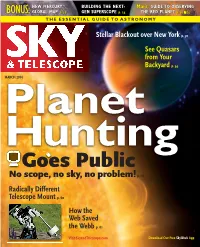

Goes Public No Scope, No Sky, No Problem! P

BONUS: NEW MERCURY BUILDING THE NEXT- Mars: GUIDE TO OBSERVING GLOBALG MAP p. 39 GEN SUPERSCOPE p. 24 THE RED PLANET p. 50 & 54 THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO ASTRONOMY Stellar Blackout over New York p. 30 See Quasars from Your Backyard p. 34 MARCH 2014 Planet Hunting Goes Public No scope, no sky, no problem! p. 18 Radically Different Telescope Mount p. 60 How the Web Saved the Webb p. 82 Visit SkyandTelescope.com Download Our Free SkyWeek App FC Mar2014.indd 1 12/23/13 11:51 AM Mercury Earth Meet the planet nearest our Sun Solid inner core The innermost planet has challenged astronomers for centuries. Its proximity to the Sun limits ground- Liquid Mercury outer core based telescopic observations, and when NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft made three close passes Mantle during the 1970s, the little planet appeared to have a Crust landscape that strongly resembled the Moon’s. But Mercury is no Moon. NASA’s Messenger spacecraft, in orbit around the Iron Planet since Solid inner core March 2011, has recently fi nished its initial global Moon survey. The work reveals that this wacky world has Liquid outer core a unique, complex history all its own. Mantle The survey images show a marvelous world of Solid ancient volcanic fl oods and mysteriously dark ter- inner core Crust rain (S&T: April 2012, page 26). Plains — mostly Liquid volcanic — cover about 30% of the surface. And outer core as radar images have long suggested, subsurface Mantle water ice lies tucked inside some polar craters. Crust Temperatures in the coldest craters never top 50° above absolute zero, making Mercury both one of the hottest and coldest bodies in the solar system.