Set List -- Lisa Spykers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

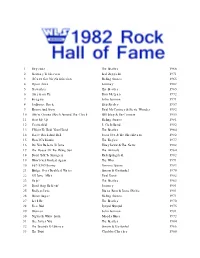

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

Audio + Video 6/8/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

New Releases WEA.CoM iSSUE 11 JUNE 8 + JUNE 15 , 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word audio + video 6/8/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- WB 522739 AGAINST ME! White Crosses $13.99 6/8/10 N/A CD- White Crosses (Limited WB 524438 AGAINST ME! Edition) $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 White Crosses (Vinyl WB A-522739 AGAINST ME! w/Download Card) $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- CUR 78977 BRICE, LEE Love Like Crazy $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 DV- WRN 523924 CUMMINS, DAN Crazy With A Capital F (DVD) $16.95 6/8/10 5/12/10 WB A-46269 FAILURE Fantastic Planet (2LP) $24.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 Selections From The Original Broadway Cast Recording CD- 'American Idiot' Featuring REP 524521 GREEN DAY Green Day $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- RRR 177972 HAIL THE VILLAIN Population: Declining $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- REP 519905 IYAZ Replay $9.94 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- FBY 524007 MCCOY, TRAVIE Lazarus $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- FBY 524670 MCCOY, TRAVIE Lazarus (Amended) $13.99 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- ATL 522495 PLIES Goon Affiliated $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 CD- ATL 522497 PLIES Goon Affiliated (Amended) $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 The Twilight Saga: Eclipse CD- Original Motion Picture ATL 523836 VARIOUS ARTISTS Soundtrack $18.98 6/8/10 5/19/10 The Twilight Saga: -

50S 60S 70S.Txt 10Cc - I'm NOT in LOVE 10Cc - the THINGS WE DO for LOVE

50s 60s 70s.txt 10cc - I'M NOT IN LOVE 10cc - THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE A TASTE OF HONEY - OOGIE OOGIE OOGIE ABBA - DANCING QUEEN ABBA - FERNANDO ABBA - I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA - KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA - MAMMA MIA ABBA - SOS ABBA - TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA - THE NAME OF THE GAME ABBA - WATERLOU AC/DC - HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC - YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE - HOW LONG ADRESSI BROTHERS - WE'VE GOT TO GET IT ON AGAIN AEROSMITH - BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH - COME TOGETHER AEROSMITH - DREAM ON AEROSMITH - LAST CHILD AEROSMITH - SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH - WALK THIS WAY ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DAMNED IF I DO ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DOCTOR TAR AND PROFESSOR FETHER ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - I WOULDNT WANT TO BE LIKE YOU ALBERT, MORRIS - FEELINGS ALIVE N KICKIN - TIGHTER TIGHTER ALLMAN BROTHERS - JESSICA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MELISSA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALLMAN BROTHERS - RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROTHERS - REVIVAL ALLMAN BROTHERS - SOUTHBOUND ALLMAN BROTHERS - WHIPPING POST ALLMAN, GREG - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALPERT, HERB - RISE AMAZING RHYTHM ACES - THIRD RATE ROMANCE AMBROSIA - BIGGEST PART OF ME AMBROSIA - HOLDING ON TO YESTERDAY AMBROSIA - HOW MUCH I FEEL AMBROSIA - YOU'RE THE ONLY WOMAN AMERICA - DAISY JANE AMERICA - HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA - I NEED YOU AMERICA - LONELY PEOPLE AMERICA - SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA - TIN MAN Page 1 50s 60s 70s.txt AMERICA - VENTURA HIGHWAY ANDERSON, LYNN - ROSE GARDEN ANDREA TRUE CONNECTION - MORE MORE MORE ANKA, PAUL - HAVING MY BABY APOLLO 100 - JOY ARGENT - HOLD YOUR HEAD UP ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - DO IT OR DIE ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - IMAGINARY LOVER ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - SO IN TO YOU AVALON, FRANKIE - VENUS AVERAGE WHITE BD - CUT THE CAKE AVERAGE WHITE BD - PICK UP THE PIECES B.T. -

Boarh to Increase Corporate-Scliool Pannersmps Ne

ARCHIVES Wednesday, October 21,1998 new federal ^| boarH to increase corporate-scliool pannersMps critics worry about wHo'li call the shots seepagel2 ne BCIT Ubrary implements new computer system seepage^ Arts&Culture ] A load of fiiffl. theatre, : concerts & CD revieuvs to sink your entertainments famished teeth into. seepagesStoM The Student Newspaper of the British Coiumbi Campus Events. Link 311432-8974: This Calendar column is open for notices of evenls on all BCIT campuses. Submissions can be faxed to 431-7619. sent by campus mail or dropped off at The Link office in the SA Campus Centre (down the corridor between the video arcade and the vacant store) Unclassifieds] nelink Wednesday, October 21 Friday, October 30 4' X 4' SOLID PINE DRAFTING | BACCHUS TABLE with some equipment $175. Legal Aid. Free Consullation. 1:30 Electronics: Term A Courses End. 739-7390. to 3:30pm. By appoinlment. By Alcohol Awareness phone consultation 432-8600. Save the Tiger Walk '98. Is the Student newspaper of Week Events the British Columbia Counselling Workshop: Writing Saturday, October 31 Institute of Technology. October 26-30 Published bi-weckly by Successful Exams. Noon- 1:30pm. the BCIT Student Association, SWI 1125 (near Employment Hallowe'en The Ltnk circulates 3,500 copies Services). Information Tables in the to over 16,000 sludents and slaff. Great HaU. MADD, AA, BCIT Tap into Monday, November 2 Saturday, October 10 Health Services, The Driving American Marketing Association Alternative, BACCHUS and BCIT's United Nations Day. Meeting. 7:15am. SA Boardroom, ICBC. Contributors: SA Campus Centre. David Lai. Greg Hehen, October 26-30. -

Gramofon, 1998 (3. Évfolyam, 1-12. Szám)

Csalog Gábor Starker János Fotó: promóció Fotó: Günter Wand Don Cherry Diana Krall Aziza Mustafa Zadeh MAR TÖBB MINT EMBER HALLGATJA BUDAPESTEN! ------ # 1 «------ BUDAPEST RÁDIÓ □ F 3 V C STBBiEQ 1022 BUDAPEST, BIMBÓ ÚT 7. FAX: 2 1 2 -4 9 6 8 TELEFON: 2 1 2 -4 5 0 7 The Hungarian CD Review , • ■ . Retkes Attila Főszerkesztő Bősze Adóm lapigazgató Zipernovszky Kornél Jazzrovat-vezető Trochilus Grafikai Bt. lapterv és tipográfia A szerkesztőség Budapest Mandula utca 3 Tel./Fax: 212-4782 Internet-cím: Http:/ / www. bmc. Hu/ gramofon <7, Diana Kralt Amfisz Kft. Iványi Margó Felelős kiadó Aziza Mustafa ZadeH 1025 Budapest Mandula utca 31. Tel./fax: 212-4782 Örömmel jelentjük: Joe Zawinul és Paul McCartney után idén már a Harma dik világsztár nyilatkozott a Gramofonnak. A kortárs jazz megHatározó alak Terjeszti: ja, a nagyszerű gitáros, Pat M etHeny- aki április 28-án, saját együttesével Bu dapesten is bemutatja Imaginary Day című albumát - A Hónap interjújában a Hírker Rt., az NHE, vall pályafutásáról, stiláris és műfaji kötődéseiről. Áprilisi számunkban több A hónap interjúja: Pat MetHeny a Kiadói lapterjesztő Kft., más, megítélésünk szerint izgalmas és különleges művészportré is olvasHató: Kiadói panoráma: Erato 5 ElisabetH Leonskaya zongoraművész a Budapesti Tavaszi Fesztivál keretében járt Magyarországon; míg a csembaló virtuóza, a magyar származású Pierre Oldal Gábor: Kis magyar gromofonológia XIII. 8 Hantái a francia fővárosban osztotta meg gondolatait munkatársainkkal. Antológia: Haydn: Az évszakok 10 Lindner András sorozata, a Kiadói panoráma áprilisban a francia nemzeti Pierre Hanta'i: Egy magyar származású Hanglemezkiadás büszkeségét, az Eratót mutatja be; Oldal Gábor Kis magyar MediaTrade Bt. csembalistasztár Párizsban 12 gramofonológiája a Hatvanas évek - immár a tömegkultúrára épülő - Hangle Tel./fax: 342-2362 Beszélgetés Elisabeth Leonskayával 14 mezkiadását vizsgálja. -

98-032798.Compressed.Pdf

DANCERS DANCERS VIP 6PM-CLOSE 25¢ DRAFT 6PM-CLOSE SPECIALS SUPER OPEN-CLOSE $1 WELL & SUNDAY BEER $1 WELL& HAPPY HOUR 10PM-11PM SHOW WET BEER 11:30PM UNDERWEAR WELL & BEER NACHA 25¢ DRAFT CONTEST 12:30 OPEN TIL TYPE'S SHOW OPEN-CLOSE CLOSE 12AM -- :Eo~ =-« III THURSDAY,. <J~APRIL 2 VOLUME 24, NUMBER 4 MARCH 27 - APRIL 2, 1998 14 MOVIES Past Haunts Present in the Gay-Themed Lilies Reviewed by Gary Laird 21 LOOKING BACK Death of an Idol, Part II: Then What Happened? by Phil Johnson 26 FRESH BEATS New Album from Aretha Franklin, New Singles from Moloko and Joee by Jimmy Smith 31 HIGHLIGHT Houston's Diana Foundation Presents 44th Annual Awards Show 39 CURRENT EVENTS 47 BACKSTAGE Dallas Theater Center Presents Having Our Say April 1-26 50 ON OUR COVER Joshua A. Thompson of Fort Worth photos by Jerry Stevens 53 LETTERSTO THE EDITOR 57 STARSCOPE Mercury's Course Through the Cosmos Disrupts the Zodiac 68 TEXAS NEWS 75 TEXAS TEA 86 CLASSIFIEDS 93 GUIDE 1WT (This Week In Texas) Is published by Texas Weekly Times Newspaper Co" at 3300 Reagan Street In Dallas, Texas 75219 and 811 Westhelmer In Houston, Texas 77006. Opinions expressed by columnists are not necessarily those of TWTor of Its staff. Publication of the MOlY name or photograph of any person or organization in articles or advertising in TWTis not to be construed as any Indication of the sex- ual orientation of said person or organization. Subscription rates: 579 per year, $40 per half year. Back Issues available at $2 each. -

ALL-2017 \226 Bele\236Nica

ALL-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 334 0 334 ŠANK ROCK - NEKAJ VEČ 2 269 0 269 LOS VENTILOS - ČAS 3 262 0 262 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABEND - GREVA NAPREJ 4 238 0 238 RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS - SICK LOVE 5 230 0 230 NIKA ZORJAN - FSE 6 229 0 229 CHAINSMOKERS - PARIS 7 226 1 227 DNCE & NICKI MINAJ - KISSING STRANGERS 8 226 0 226 NINA PUŠLAR - ZA VEDNO 9 200 0 200 ALICE MERTON - NO ROOTS 10 198 0 198 SKALP - HLADEN TUŠ 11 196 0 196 BQL - MUZA 12 195 0 195 KINGS OF LEON - FIND ME 13 195 1 196 RUSKO RICHIE & ROKO BAŽIKA - ZBOG NJE 14 192 0 192 ALYA - HALO 15 190 0 190 NEISHA - VRHOVI 16 185 0 185 DISTURBED - THE SOUND OF SILENCE 17 179 0 179 MI2 - LANSKI SNEG 18 175 0 175 KATY PERRY - CHAINED TO THE RHYTM 19 173 0 173 LITTLE MIX & CHARLIE PUTH - OOPS 20 172 2 174 ED SHEERAN - GALWAY GIRL 21 169 0 169 SIA - MOVE YOUR BODY 22 169 0 169 LINKIN PARK feat. KIIARA - HEAVY 23 167 0 167 ANABEL - OB KAVI 24 164 0 164 ED SHEERAN - SHAPE OF YOU 25 161 1 162 BOHEM - BALADA O NJEJ 26 158 0 158 JAN PLESTENJAK - IZ ZADNJE VRSTE 27 157 0 157 SIDDHARTA - DOLGA POT DOMOV 28 156 0 156 SELL OUT - NI PANIKE 29 156 1 157 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 30 153 0 153 HARRY STYLES - SIGN OF THE TIMES 31 151 0 151 ED SHEERAN - CASTLE ON THE HILL 32 151 0 151 MAROON 5 & FUTURE - COLD 33 145 0 145 LEONART - DANES ME NI 34 145 1 146 RICKY MARTIN & MALUMA - VENTE PA'CA 35 145 0 145 ED SHEERAN - HOW WOULD YOU FEEL 36 144 0 144 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - STARBOY 37 143 0 143 BQL - HEART OF GOLD 38 143 1 144 RAIVEN - ZAŽARIM 39 143 0 143 STING - I CAN'T STOP THINKING ABOUT YOU 40 142 0 142 -

Punk / Dark / Wave / Indie / Alternative Sat, 21

Punk / Dark / Wave / Indie / Alternative www.redmoonrecords.com Artista Titolo ID Formato Etichetta Stampa N°Cat. / Barcode Condition Price Note 'TIL TUESDAY Welcome home 13217 1xLP Epic CBS NL EPC57094 EX+/EX 12,00 € 'TIL TUESDAY What about love 18067 1x12" Epic CBS UK 6501256 EX/EX 8,00 € 20-20s 20-20s 22418 1xCD Astralwerks USA 7242386093424 USED 7,00 € 20-20s Shake/shiver/moan 22419 1xCD TBD records USA 880882170721 USED 7,00 € Cardsleeve 3 COLOURS RED Beautiful day (3 tracks) 8725 1xCDs Creation rec. UK 50175556703083 USED 2,60 € 411 (four one one) This isn't me 16084 1xCD Cargo rec. USA 723248300427 USED 8,00 € 60ft DOLLS Alison's room (4 tracks) 7869 1xCDs Indolent BMG EU 743215668022 USED 2,60 € A CERTAIN RATIO Good together 8872 1xLP A&M Polygram UK 397011-1 EX+/EX 12,90 € A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS (It's not me) 19956 1x7" Jive Zomba GER 6.13928AC EX+/EX 6,00 € talking\Tanglimara A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I ran (Die Krupps 15005 1x12" Cleopatra USA CLP0590-1 SS 10,00 € remix)\Space age love song (KMFDM remix) A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Never again (the 18502 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.14237 EX+/EX 6,00 € dancer)\Living in heaven A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Nightmares \ 16984 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.13801 JIVE33 EX+/EX 6,00 € Rosenmontag A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Transfer affection\I ran 18501 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.13876AC EX+/EX 6,00 € (live vers.) A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS Who's that girl? She's got 1989 1x7" Jive Teldec GER 6.14470AC EX+/EX+ 6,00 € it (vocal+instr.) A SOMETIMES PROMISE / 3 LETTER ENGAGEMENT 30 seconds in the police 5625 1x7"EP Stratagem USA SRC003 EX+/EX 6,00 € Split EP With inserts station ripcords A TESTA BASSA Clone o.g.m. -

Download Song List

PURPLE RAIN PRINCE BLISTER IN THE SUN VIOLENT FEMMES 3AM MATCHBOX 20 BLUE SUEDE SHOES CARL PERKINS 500 MILES THE PROCLAIMERS BLUEBERRY HILL FATS DOMINO CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL BOOT SCOOTIN’ BOOGIE BROOKS & DUNN 867-5309 (JENNY) TOMMY TUTONE BORN TO BE WILD STEPPENWOLF IN THE AIR TONIGHT PHIL COLLINS BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN YOU CAN’T HURRY LOVE PHIL COLLINS BRANDY LOOKING GLASS AFRICA TOTO BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S DEEP BLUE SOMETHING ROSANNA TOTO BRICK HOUSE THE COMMODORES AIN’T TOO PROUD TO BEG THE TEMPTATIONS BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATERS SIMON & MY GIRL THE TEMPTATIONS GARFUNKEL ALL ABOUT THE BASS MEGHAN TRAINOR BROWN EYED GIRL VAN MORRISON ALL APOLOGIES NIRVANA BUILD ME UP BUTTERCUP THE FOUNDATIONS ALL FOR YOU SISTER HAZEL BYE BYE LOVE THE EVERLY BROTHERS ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’ THE MAMAS & THE PAPAS ALL OF ME JOHN LEGEND CANDLE IN THE WIND ELTON JOHN ALL SHOOK UP ELVIS PRESLEY CAN’T BUY ME LOVE THE BEATLES ALL SUMMER LONG KID ROCK CAN’T FIGHT THIS FEELING REO SPEEDWAGON ALLENTOWN BILLY JOEL CAN’T GET ENOUGH BAD COMPANY ALREADY GONE EAGLES CAN’T SMILE WITHOUT YOU BARRY MANILOW ALWAYS SOMETHING THERE TO REMIND ME CAN’T TAKE MY EYES OFF OF YOU FRANKIE VALLI NAKED EYES CAN’T YOU SEE MARSHALL TUCKER BAND AMERICA NEIL DIAMOND CAPTAIN JACK BILLY JOEL AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN CECILIA SIMON & GARFUNKEL AMIE PURE PRAIRIE LEAGUE CELEBRATION KOOL & THE GANG ANGEL EYES JEFF HEALEY BAND CENTERFIELD JOHN FOGERTY ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL PINK FLOYD CENTERFOLD J. GILES BAND ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT SAM COOKE CHAMPAGNE -

The BG News October 2, 1998

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-2-1998 The BG News October 2, 1998 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 2, 1998" (1998). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6377. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6377 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. FRIDAY,The Oct. 2, 1998 A dailyBG independent student News press Volume 85« No. 28 Bigshots Registration process changes corrected to Mark's new registra- ic affairs, said he thought the some majors have lower GPA's □ Bigshots is changing old process of seniors, fresh- than others. Registration 1 tion process alters the men, juniors, sophomores, Boutelle said he has heard its name back to order students can graduate students and guests this argument, but doesn't Priority Order Mark's Pub. register. was the end product, but it was- know which majors have lower n't. GPA's. •Seniors "It was a good idea (the old "Those students who have By TRACY WOOD ■ The Falcons are hop- By MELISSA NAYM1K process), but the time wasn't low to middle GPA's are always •Juniors The BG News ing for the first win of the right," Richardson said. -

Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Quatro

Patoski: Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Cuatro “Uno, Dos, One, T That count-off introduction to “Wooly Bully,” the song that forever etched Sam Samudio into the institutional memory of pop as Sam the Sham, the turbaned hepcat who led his Pharoahs out of the east Dallas barrio to the big time, holds the key to understanding Tex- Mex and where it fits in the cosmos of all things rock and roll.The rest of the modern world may have perceived the bilingual enumeration as some kind of exotic confection, an unconven- tional beginning to a giddy rhythm ride of in- sane craziness. For Samudio, though, scream- ing “uno, dos, one, two, tres, cuatro” was just doing what comes naturally to a teenager growing up in two cultures in a place not far from the Rio Grande where the First World meets the Third World, and where the Tex meets the Mex. 12 Produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2001 1 Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 1 [2001], Iss. 1, Art. 3 “Uno, Dos, One, Dos, “Uno, .” Two, . Quatro. Tres, Two, Tres, Quatro. .” By Joe Nick Patoski It’s been an ongoing process since Germans and Bohemians broken into the mainstream with his 1956 Top 40 hit sung in bearing accordions arrived in the Texas-Mexico borderlands fresh English, “Wasted Days, Wasted Nights,” a guaranteed bellyrubber off the boat from Europe as early as the 1840s. Their traditions on the dance floor. and instruments were quickly embraced by Mexican Texans, or In fact, Mexican Americans all over Texas were doing their own Tejanos, who picked up the squeezebox and incorporated polkas, interpretation of rock and roll, filtering it through an ethnic gauze waltzes, the schottische and the redowa into their dance reper- that rendered the music slower and more rhythm-heavy, swaying toires alongside rancheras, boleros, and huapangos.