N December 1958, Ritchie Valens Paid A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Can Hear Music

5 I CAN HEAR MUSIC 1969–1970 “Aquarius,” “Let the Sunshine In” » The 5th Dimension “Crimson and Clover” » Tommy James and the Shondells “Get Back,” “Come Together” » The Beatles “Honky Tonk Women” » Rolling Stones “Everyday People” » Sly and the Family Stone “Proud Mary,” “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Green River,” “Traveling Band” » Creedence Clearwater Revival “In-a-Gadda-Da-Vida” » Iron Butterfly “Mama Told Me Not to Come” » Three Dog Night “All Right Now” » Free “Evil Ways” » Santanaproof “Ride Captain Ride” » Blues Image Songs! The entire Gainesville music scene was built around songs: Top Forty songs on the radio, songs on albums, original songs performed on stage by bands and other musical ensembles. The late sixties was a golden age of rock and pop music and the rise of the rock band as a musical entity. As the counterculture marched for equal rights and against the war in Vietnam, a sonic revolution was occurring in the recording studio and on the concert stage. New sounds were being created through multitrack recording techniques, and record producers such as Phil Spector and George Martin became integral parts of the creative process. Musicians expanded their sonic palette by experimenting with the sounds of sitar, and through sound-modifying electronic ef- fects such as the wah-wah pedal, fuzz tone, and the Echoplex tape-de- lay unit, as well as a variety of new electronic keyboard instruments and synthesizers. The sound of every musical instrument contributed toward the overall sound of a performance or recording, and bands were begin- ning to expand beyond the core of drums, bass, and a couple guitars. -

Silly Love Songs

Wk 25 – 1976 June 19 – USA Top 100 1 1 11 SILLY LOVE SONGS Wings 2 2 15 GET UP AND BOOGIE Silver Convention 3 3 14 MISTY BLUE Dorothy Moore 4 4 12 LOVE HANGOVER Diana Ross 5 7 21 SARA SMILE Hall & Oates 6 6 17 SHANNON Henry Gross 7 8 8 SHOP AROUND Captain & Tennille 8 9 15 MORE MORE MORE Andrea True Connection 9 25 7 AFTERNOON DELIGHT Starland Vocal Band 10 13 8 I'LL BE GOOD TO YOU Brothers Johnson 11 5 12 HAPPY DAYS Pratt & McClain 12 21 10 KISS AND SAY GOODBYE Manhattans 13 15 10 LOVE IS ALIVE Gary Wright 14 16 10 TAKIN' IT TO THE STREETS Doobie Brothers 15 17 12 MOVIN' Brass Construction 16 18 9 I WANT YOU Marvin Gaye 17 19 8 NEVER GONNA FALL IN LOVE AGAIN Eric Carmen 18 24 10 MOONLIGHT FEELS RIGHT Starbuck 19 23 7 TAKE THE MONEY AND RUN Steve Miller Band 20 20 11 BARETTA'S THEME Rhythm Heritage 21 10 9 FOOL TO CRY Rolling Stones 22 26 6 THE BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN Thin Lizzy 23 11 16 RIHANNON Fleetwood Mac 24 12 13 WELCOME BACK John Sebastian 25 14 19 BOOGIE FEVER Sylvers 26 30 10 GET CLOSER Seals & Crofts 27 32 5 YOU'RE MY BEST FRIEND Queen 28 34 11 THAT'S WHERE THE HAPPY PEOPLE GO Trammps 29 54 2 GOT TO GET YOU INTO MY LIFE Beatles 30 35 6 TODAY'S THE DAY America 31 36 8 LET HER IN John Travolta 32 38 7 MAKING OUR DREAMS COME TRUE Cyndi Grecco 33 37 6 TEAR THE ROOF OFF THE SUCKER Parliament 34 22 16 FOOLED AROUND AND FELL IN LOVE Elvin Bishop 35 42 7 SAVE YOUR KISSES FOR ME Brotherhood Of Man 36 41 11 TURN THE BEAT AROUND Vicki Sue Robinson 37 40 7 I'M EASY Keith Carradine 38 27 19 RIGHT BACK WHERE WE STARTED Maxine Nightingale 39 43 5 MAMMA MIA Abba 40 58 3 ROCK & ROLL MUSIC Beach Boys 41 51 3 SOMEBODY'S GETTING IT Johnnie Taylor 42 52 2 LAST CHILD Aerosmith 43 53 4 SOPHISTICATED LADY Natalie Cole 44 50 4 YOUNG HEARTS RUN FREE Candi Staton 45 55 2 I NEED TO BE IN LOVE Carpenters 46 46 7 YES YES YES Bill Cosby 47 57 4 WHO LOVES YOU BETTER Isley Brothers 48 45 9 THINKING OF YOU Paul Davis 49 59 4 A FIFTH OF BEETHOVEN Walter Murphy 50 60 3 GOOD VIBRATIONS Todd Rundgren 51 61 4 SILVER STAR Four Seasons 52 56 3 CAN'T STOP GROOVIN' NOW B.T. -

Grabación, Producción Y Finalización De Un Producto Discográfico En Dolby 5.1 Conteniendo Dos Géneros Disímiles

GRABACIÓN, PRODUCCIÓN Y FINALIZACIÓN DE UN PRODUCTO DISCOGRÁFICO EN DOLBY 5.1 CONTENIENDO DOS GÉNEROS DISÍMILES CARLOS MARIO BENÍTEZ HOYOS ANDRÉS FELIPE RAMOS LÓPEZ PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTÁ 2009 GRABACIÓN, PRODUCCIÓN Y FINALIZACIÓN DE UN PRODUCTO DISCOGRÁFICO EN DOLBY 5.1 CONTENIENDO DOS GÉNEROS DISÍMILES CARLOS MARIO BENÍTEZ HOYOS ANDRÉS FELIPE RAMOS LÓPEZ Proyecto de grado presentado para optar el título de MAESTRO EN MÚSICA CON ÉNFASIS EN INGENIERÍA DE SONIDO Director RICARDO ESCALLÓN GAVIRIA Ingeniero de Sonido PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA FACULTAD DE ARTES CARRERA DE ESTUDIOS MUSICALES BOGOTÁ 2009 4 CONTENIDO INTRODUCCIÓN JUSTIFICACIÓN OBJETIVOS 1. SUSTENTO DEL MATERIAL ARTÍSTICO DESDE EL CONCEPTO WALL OF SOUND ...............................................................p.13 2. LAS DIVERSAS FORMAS DE CREACIÓN DE WALL OF SOUND……..p.17 3. ARTISTAS Y ESTILOS DEL SIGLO XX INVOLUCRADOS………………p.23 4. BREVE HISTORIA DEL SONIDO ENVOLVENTE (SURROUND 5.1)…………………………………………..p.35 5. CONCEPTOS DE INGENIERÍA APLICADOS A GRABACIÓN Y MEZCLA SURROUND………………………………………………………..p.38 6. ANÁLISIS DE DISCOGRAFÍAS……………………………………………..p.48 7. BITÁCORA DE GRABACIÓN Y PRODUCCIÓN…………………………..p.68 8. PROCESO DE EDICIÓN DEL REPERTORIO CLÁSICO……………… p.106 9. DESCRIPCIÓN GENERAL DE LOS PROCESOS DE MEZCLA……….p.112 10. CONCLUSIONES…………………………………………………………….p.124 11. BIBLIOGRAFÍA……………………………………………………………….p.128 5 INTRODUCCIÓN Las convenciones de la industria musical, en donde los arreglos, la instrumentación y el diseño general de una pieza, se producen en serie bajo un esquema determinado por el objetivo único de alcanzar afinidad en un mercado o grupo especifico, con fines claramente comerciales, han mostrado formas preconcebidas de cómo elaborar un material discográfico en todas sus etapas. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Austinmusicawards2017.Pdf

Jo Carol Pierce, 1993 Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and PHOTOS BY MARTHA GRENON MARTHA BY PHOTOS Joe Ely, 1990 Daniel Johnston, Living in a Dream 1990 35 YEARS OF THE AUSTIN MUSIC AWARDS BY DOUG FREEMAN n retrospect, confrontation seemed almost a genre taking up the gauntlet after Nelson’s clashing,” admits Moser with a mixture of The Big Boys broil through trademark inevitable. Everyone saw it coming, but no outlaw country of the Seventies. Then Stevie pride and regret at the booking and subse- confrontational catharsis, Biscuit spitting one recalls exactly what set it off. Ray Vaughan called just prior to the date to quent melee. “What I remember of the night is beer onto the crowd during “Movies” and rip- I Blame the Big Boys, whose scathing punk ask if his band could play a surprise set. The that tensions started brewing from the outset ping open a bag of trash to sling around for a classed-up Austin Music Awards show booking, like the entire evening, transpired so between the staff of the Opera House, which the stage as the mosh pit gains momentum audience visited the genre’s desired effect on casually that Moser had almost forgotten until was largely made up of older hippies of a Willie during “TV.” the era. Blame the security at the Austin Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan walked in Nelson persuasion who didn’t take very kindly About 10 minutes in, as the quartet sears into Opera House, bikers and ex-Navy SEALs from with Double Trouble and to the Big Boys, and the Big “Complete Control,” security charges from the Willie Nelson’s road crew, who typical of the proceeded to unleash a dev- ANY HISTORY OF Boys themselves, who were stage wings at the first stage divers. -

Barbara L. Johnson Chair, Pro Bono and Community Employment Law

Chair's Corner PBN Features Atlanta Beijing London Los Angeles Barbara L. Johnson Chair, Pro Bono and Community Milan Employment Law Partner New York Welcome to the current issue of Pro Bono News. I am pleased to report that in 2008, our attorneys dedicated more than Orange County 68,000 hours of pro bono and community service work, a 58% increase from the previous year. San Diego Inspired by the Paul Hastings Pro Bono Challenge (a firmwide San Francisco initiative aimed at increasing the number of pro bono hours per attorney from 25 to 75 annually), lawyers at all levels Shanghai increased their pro bono participation, with 83.1 hours logged on average per attorney. Washington, D.C. At the Firm’s recent Partner’s Retreat, Paris partner Dominique Borde was named the recipient of the 2009 Resources Hastings Award for Community Service, an honor given to a firm partner who demonstrates sustained leadership in Office Contacts: community and pro bono service. A long-time board member Pro Bono & of Doctors Without Borders, Dominique has devoted hundreds Community of pro bono work hours to support causes as diverse as helping Committee visual artists to obtain licensing agreements to assisting Afghan women in their pursuit of education and equal rights. Congratulations to Dominique for his pro bono commitment! This year, we are challenging every Paul Hastings attorney to increase his/her commitment to pro bono legal services and have created the Global Pro Bono Hours Recognition Program to recognize attorneys for their local and global efforts. Award winners will be announced in a special edition of Pro Bono News. -

Sir Douglas Quintet

Sir Douglas Quintet The Sir Douglas Quintet: Emerging from San Antonio‟s “West Side Sound,” The Sir Douglas Quintet blended rhythm and blues, country, rock, pop, and conjunto to create a unique musical concoction that gained international popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. From 1964 to 1972, the band recorded five albums in California and Texas, and, although its founder, Doug Sahm, released two additional albums under the same group name in the 1980s and 1990s, the Quintet never enjoyed the same domestic success as it had during the late 1960s. A big part of the Sir Douglas Quintet‟s distinctive sound derived from the unique musical environment in which its members were raised in San Antonio. During the 1950s and 1960s, the “moderate racial climate” and ethnically diverse culture of San Antonio—caused in part by the several desegregated military bases and the large Mexican-American population there—allowed for an eclectic cross- pollination of musical styles that reached across racial and class lines. As a result, Sahm and his musical friends helped create what came to be known as the “West Side Sound,” a dynamic blending of blues, rock, pop, country, conjunto, polka, R&B, and other regional and ethnic musical styles into a truly unique musical amalgamation. San Antonio-based artists, such as Augie Meyers, Doug Sahm, Flaco Jiménez, and Sunny Ozuna, would help to propel this sound onto the international stage. Born November 6, 1941, Douglas Wayne Sahm grew up on the predominately-black east side of San Antonio. As a child, he became proficient on a number of musical instruments and even turned down a spot on the Grand Ole Opry (while still in junior high school) in order to finish his education. -

San Antonio's West Side Sound

Olsen: San Antonio's West Side Sound San Antonio’s SideSound West Antonio’s San West Side Sound The West Side Sound is a remarkable they all played an important role in shaping this genre, Allen O. Olsen amalgamation of different ethnic beginning as early as the 1950s. Charlie Alvarado, Armando musical influences found in and around Almendarez (better known as Mando Cavallero), Frank San Antonio in South-Central Texas. It Rodarte, Sonny Ace, Clifford Scott, and Vernon “Spot” Barnett includes blues, conjunto, country, all contributed to the creation of the West Side Sound in one rhythm and blues, polka, swamp pop, way or another. Alvarado’s band, Charlie and the Jives, had such rock and roll, and other seemingly regional hits in 1959 as “For the Rest of My Life” and “My disparate styles. All of these have Angel of Love.” Cavallero had an influential conjunto group somehow been woven together into a called San Antonio Allegre that played live every Sunday sound that has captured the attention of morning on Radio KIWW.5 fans worldwide. In a sense, the very Almendarez formed several groups, including the popular eclectic nature of the West Side Sound rock and roll band Mando and the Chili Peppers. Rodarte led reflects the larger musical environment a group called the Del Kings, which formed in San Antonio of Texas, in which a number of ethnic during the late 1950s, and brought the West Side Sound to Las communities over the centuries have Vegas as the house band for the Sahara Club, where they exchanged musical traditions in a remained for nearly ten years.6 Sonny Ace had a number of prolific “cross-pollination” of cultures. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BILL HOLMAN NEA Jazz Master (2010) Interviewee: Bill Holman (May 21, 1927 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: February 18-19, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 84 pp. Brown: Today is Thursday, February 18th, 2010, and this is the Smithsonian Institution National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Oral History Program interview with Bill Holman in his house in Los Angeles, California. Good afternoon, Bill, accompanied by his wife, Nancy. This interview is conducted by Anthony Brown with Ken Kimery. Bill, if we could start with you stating your full name, your birth date, and where you were born. Holman: My full name is Willis Leonard Holman. I was born in Olive, California, May 21st, 1927. Brown: Where exactly is Olive, California? Holman: Strange you should ask [laughs]. Now it‟s a part of Orange, California. You may not know where Orange is either. Orange is near Santa Ana, which is the county seat of Orange County, California. I don‟t know if Olive was a part of Orange at the time, or whether Orange has just grown up around it, or what. But it‟s located in the city of Orange, although I think it‟s a separate municipality. Anyway, it was a really small town. I always say there was a couple of orange-packing houses and a railroad spur. Probably more than that, but not a whole lot. -

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

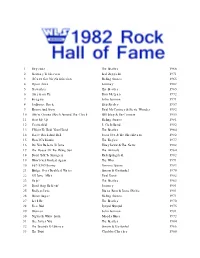

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

My Guitar Is a Camera

My Guitar Is a Camera John and Robin Dickson Series in Texas Music Sponsored by the Center for Texas Music History Texas State University–San Marcos Gary Hartman, General Editor Casey_pages.indd 1 7/10/17 10:23 AM Contents Foreword ix Steve Miller Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Tom Reynolds From Hendrix to Now: Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey xv Herman Bennett, with Watt M. Casey Jr. 1. Witnesses: The Music, the Wizard, and Me 1 Mark Seal 2. At Home and on the Road: 1970–1975 11 3. Got Them Texas Blues: Early Days at Antone’s 31 4. Rolling Thunder: Dylan, Guitar Gods, and Joni 54 5. Willie, Sir Douglas, and the Austin Music Creation Myth 60 Joe Nick Patoski 6. Cosmic Cowboys and Heavenly Hippies: The Armadillo and Elsewhere 68 7. The Boss in Texas and the USA 96 8. And What Has Happened Since 104 Photographer and Contributors 123 Index 125 Casey_pages.indd 7 7/10/17 10:23 AM Casey_pages.indd 10 7/10/17 10:23 AM Jimi Hendrix poster. Courtesy Paul Gongaware and Concerts West. Casey_pages.indd 14 7/10/17 10:24 AM From Hendrix to Now Watt, His Camera, and His Odyssey HERMAN BENNETT, WITH WATT M. CASEY JR. Watt Casey’s journey as a photographer can be In the summer of 1970, Watt arrived in Aus- traced back to an event on May 10, 1970, at San tin with the intention of getting a degree from Antonio’s Hemisphere Arena: the Cry of Love the University of Texas. Having heard about a Tour. -

Salsa2bills 1..3

By:AAOrtiz, Jr. H.R.ANo.A796 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, Nearly 2-1/2 years have gone by since Freddy Fender 2 died on October 14, 2006, but the passage of time has in no way 3 diminished the stature of this Texas music legend, and his legacy 4 remains as poignant as ever; and 5 WHEREAS, Born Baldemar Huerta on June 4, 1937, in the South 6 Texas town of San Benito, he began singing at a young age and 7 originally focused on performing the conjunto, Tejano, and 8 traditional Mexican music that was popular in his Hispanic 9 neighborhood; after serving three years in the U.S. Marine Corps, 10 he launched his music career in the late 1950s by playing Texas 11 honky-tonks and recording Spanish versions of popular hits by other 12 performers; when Imperial Records offered him a contract in 1959, 13 he adopted the stage name Freddy Fender; and 14 WHEREAS, The following year, that name became well known all 15 across the country as Mr. Fender 's song "Wasted Days and Wasted 16 Nights" became a national hit; sadly, his good fortune was 17 short-lived, as an arrest for possession of a small amount of 18 marijuana led to a three-year prison term in Louisiana; by the late 19 1960s, he had returned to the Rio Grande Valley, where he earned a 20 living as a mechanic, playing music only on the weekends; and 21 WHEREAS, Mr. Fender 's talent refused to be denied, however, 22 and in 1975, his career was reborn when "Before the Next Teardrop 23 Falls" became a number one hit on both the pop and country charts; 24 he followed "Teardrop" with a remake of his original hit, "Wasted 81R9785 JH-D 1 H.R.ANo.A796 1 Days and Wasted Nights," and it once again swept the country, 2 becoming his second consecutive number one country song; two more 3 number one smashes from the same multi-platinum album confirmed his 4 status as a major country music star and earned him the 1975 Best 5 Male Artist award from Billboard magazine; and 6 WHEREAS, Ever the versatile performer, Mr.