PROCREATIVE ICONS: ABUNDANCE and SCARCITY in Pre-Columbian Art from Peru to Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824)

Spanish Impact on Peru (1520 - 1824) San Francisco Cathedral (Lima) Michelle Selvans Setting the stage in Peru • Vast Incan empire • 1520 - 30: epidemics halved population (reduced population by 80% in 1500s) • Incan emperor and heir died of measles • 5-year civil war Setting the stage in Spain • Iberian peninsula recently united after 700 years of fighting • Moors and Jews expelled • Religious zeal a driving social force • Highly developed military infrastructure 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Lima established • Civil war between ruling Spaniards • 500 positions of governance given to Spaniards, as encomiendas 1532 - 1548, Spanish takeover of Incan empire • Silver mining began, with forced labor • Taki Onqoy resistance (‘dancing sickness’) • Spaniards pushed linguistic unification (Quechua) 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Silver and mercury mines • Reducciones used to force conversion to Christianity, control labor • Monetary economy, requiring labor from ‘free wage’ workers 1550 - 1650, shift to extraction of mineral wealth • Haciendas more common: Spanish and Creole owned land, worked by Andean people • Remnants of subsistence-based indigenous communities • Corregidores and curacas as go- betweens Patron saints established • Arequipa, 1600: Ubinas volcano erupted, therefor St. Gerano • Arequipa, 1687: earthquake, so St. Martha • Cusco, 1650: earthquake, crucifix survived, so El Senor de los Temblores • Lima, 1651: earthquake, crucifixion scene survived, so El Senor de los Milagros By 1700s, shift -

Jorge Basadre's “Peruvian History of Peru,”

Jorge Basadre’s “Peruvian History of Peru,” or the Poetic Aporia of Historicism Mark Thurner We need a Peruvian history of Peru. By Peruvian history of Peru I mean a history that studies the past of this land from the point of view of the formation of Peru itself. We must insist upon an authentic history ‘of ’ Peru, that is, of Peru as an idea and entity that is born, grows, and develops. The most important personage in Peruvian history is Peru. Jorge Basadre, Meditaciones sobre el destino histórico del Perú Although many gifted historians graced the stage of twentieth-century Peru- vian letters, Jorge Basadre Grohmann (1903 – 1980) was clearly the dominant figure. Today Basadre is universally celebrated as the country’s most sagacious and representative historian, and he is commonly referred to as “our historian of the Republic.” Libraries, avenues, and colleges are named after him. The year 2003 was “The Year of Basadre” in Peru, with nearly every major cultural institution in Lima organizing an event in his honor.1 The National University HAHR editors and the anonymous readers of earlier versions of this article deserve my thanks. Support from the Social Science Research Council, the Fulbright-Hays Program, and the University of Florida is gratefully acknowledged. All translations are mine. 1. There is no systematic work on Basadre, but several Peruvian scholars have reflected upon aspects of his work, and the centennial celebration has prompted the publication of conference proceedings. See Pablo Macera, Conversaciones con Basadre (Lima: Mosca Azul, 1979); Alberto Flores Galindo, “Jorge Basadre o la voluntad de persistir,” Allpanchis 14, no. -

Peru's Musical Heritage of the Viceroyalty: the Creation of a National Identity

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2019 Peru's Musical Heritage of the Viceroyalty: The Creation of a National Identity Fabiola Yupari Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Yupari, Fabiola, "Peru's Musical Heritage of the Viceroyalty: The Creation of a National Identity" (2019). WWU Graduate School Collection. 887. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/887 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peru’s Musical Heritage of the Viceroyalty: The Creation of a National Identity By Fabiola Yupari Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil Van Boer Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel Dr. Patrick Roulet GRADUATE SCHOOL Kathleen L. Kitto, Acting Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru

AC 2011-2240: MATHEMATICS AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE INCAS IN PERU Cheri Shakiban, University of St. Thomas I am a professor of mathematics at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I have been a faculty member since 1983. I received my Ph.D. in 1979 from Brown University in Formal Cal- culus of Variations. My recent area of research is mostly in computer vision, with applications to object recognition. My publications are in diverse areas of mathematics and engineering. I love to work with undergraduate students, in particular, underrepresented students, to get them involved in doing research in mathematics and encourage them to give conference presentations/posters and submit their work for publication. In addition to teaching regular math courses, I also like to create and teach innovative courses such as ”Mathematical symmetry of Southern Spain” and ”Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru”, which I have taught as study abroad courses several times. Michael P. Hennessey, University of St. Thomas Michael P. Hennessey (Mike) joined the full-time faculty as an Assistant Professor fall semester 2000. He is an expert in machine design, computer-aided-engineering, and in the kinematics, dynamics, and control of mechanical systems, along with related areas of applied mathematics. Presently, he has published 41 technical papers (published or accepted), in journals (9), conferences (31), or magazines (1). In 2006 he was tenured and promoted to the rank of Associate Professor. Mike gained 10 years of industrial and academic research lab experience at 3M, FMC, and the University of Minnesota prior to embarking on an academic career at Rochester Institute of Technology (3 years) and Minnesota State University, Mankato (2 years). -

CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26

Arrive: 0800 Tuesday November 22 CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26 Brief Overview: A traveler’s paradise, the warm arms of Peru envelope some of the world’s most timeless traditions and greatest ancient treasures! From its immense biodiversity, the breathtaking beauty of the Andes Mountains (the longest in the world!) and the Sacred Valley, to relics of the Incan Empire, like Machu Picchu, and the rich cultural diversity that populates the country today – Peru has an experience for everyone. Located in the Lima Metropolitan Area, the port of Callao is just a stone’s throw away from the dazzling sights and sounds of Peru’s capital and largest city, Lima. With its colorful buildings teeming with colonial architecture and verdant coastline cliffs, this vibrant city makes for a home-away-from-home during your port stay in Peru. Nearby: Explore Lima’s most iconic neighborhoods - Miraflores and Barranco – by foot, bike (PER 104-201 Biking Lima), and even Segway (PER 121-101 Lima by Segway). Be sure to hit up one of the local markets (PER 114-201 Culinary Lima) and try out Peruvian fare – you can’t go wrong with picarones (fried pumpkin dough with anis seeds and honey - pictured above), cuy (guinea pig), or huge ears of roast corn! Worth the travel: Cusco, the former capital of Incan civilization, is a short flight from Lima. From this ancient city, you can access a multitude of Andean wonders. Explore the ruins of the famed Machu Picchu, the city of Ollantaytambo – which still thrives to this day, Lake Titcaca and its many islands, and the culture of the Quechua people. -

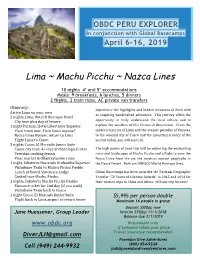

Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines

OBDC PERU EXPLORER In conjunction with Global Basecamps April 6-16, 2019 Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines 10 nights 4* and 5* accommodations Meals: 9 breakfasts, 6 lunches, 5 dinners 2 flights, 2 train rides, AC private van transfers Itinerary: Experience the highlights and hidden treasures of Peru with Arrive Lima on your own an inspiring handcrafted adventure. This journey offers the 2 nights Lima, Hotel B Boutique Hotel City tour plus day of leisure opportunity to truly understand the local culture and to 1 night Paracas, Hotel LiBertador Superior explore the wonders of this historical destination. From the Pisco town tour, Pisco Sours anyone? modern luxuries of Lima and the seaside paradise of Paracas, Nazca Lines flyover, return to Lima to the colonial city of Cusco and the mountain scenery of the Flight Lima to Cusco Sacred Valley, you will see it all. 3 nights Cusco, El Mercado Junior Suite Cusco city tour, 4+ Inca archaeological sites The high points of your trip will Be exploring the enchanting Peruvian cooking lesson ruins and landscapes of Machu Picchu and a flight to view the Pisac market & OllantaytamBo ruins Nazca Lines from the air, the mystical ancient geoglyphs in 1 night, Inkaterra Hacienda UruBamBa Superior the Nazca Desert. Both are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Vistadome Train to Machu Picchu PueBlo Lunch at famed Sanctuary Lodge GloBal Basecamps has Been awarded the National Geographic Guided tour Machu Picchu Traveler “50 Tours of Lifetime Awards” in 2015 and 2014 for 2 nights, Inkaterra Machu Picchu PueBlo their custom trips to China and Africa. -

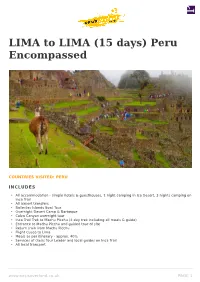

LIMA to LIMA (15 Days) Peru Encompassed

LIMA to LIMA (15 days) Peru Encompassed COUNTRIES VISITED: PERU INCLUDES • All accommodation - simple hotels & guesthouses, 1 night camping in Ica Desert, 3 nights camping on Inca Trail • All airport transfers • Ballestas Islands Boat Tour • Overnight Desert Camp & Barbeque • Colca Canyon overnight tour • Inca Trail Trek to Machu Picchu (4 day trek including all meals & guide) • Entrance to Machu Picchu and guided tour of site • Return train from Machu Picchu • Flight Cusco to Lima • Meals as per itinerary - approx. 40% • Services of Oasis Tour Leader and local guides on Inca Trail • All local transport www.oasisoverland.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)203 725 8924 EXCLUDES • Visas • National Park entrance fees totalling approx. $30 USD • International Flights • Meals not listed in the itinerary • Travel Insurance • Airport Taxes • Drinks • Optional Excursions as listed in the Pre-Departure Information • Tips TRIP ITINERARY DAYS 1 LIMA The capital of Peru, Lima is a city of contrasts. Here you'll encounter both abundant wealth and grinding poverty, modern skyscrapers next to some of the finest museums and historical monuments in Latin America. You will have a free day to explore its many museums, markets and colonial plazas. Visit the Old Town as well as the Miraflores district before watching the sunset over the Pacific Ocean at the end of the day.(No Meals) Overnight: Hotel Buena Vista (or similar) DAYS 2 LIMA TO BALLESTAS ISLANDS Our first stop, south of Lima, is the Ballestas Islands in the Paracas National Reserve. Here we take a boat trip to view one of the most important marine reserves in the world with the highest concentration of rare and exotic sea birds and sea mammals. -

Welcome to LI

Welcome to LI MFilled with opportunities 2 Begin your tour here... Lima 360° Gastronomic Lima Lima, from the The table where 04 Andes to the 14 it all comes world together History Gastronomy guide An ancient The taste of Lima 06 city 16 Map Showcase 08 Historic A crucible of center 18 products Cultural Callao 10 industries 20 The historic All the arts port Adventure Tours Outdoor Lima itinerary 12 Lima 22 Schedule 24 Lima calendar A city that looks out over the Pacific Ocean from a natural balcony, home to nearly 10 million people with countless stories, immigrants from a thousand different places. A city with a past and future, with innovators and entrepreneurs, with art, handcrafts, and industry. A city that tastes delicious and knows how to celebrate life. Lima, a city filled with opportunities. 04 Jorge Chávez Internacional Lima 360º Airport Principal Port: El Callao Lima, from the Andes to the world Located on the central coast of South America, Lima brings together the variety and complexity of an entire country in a single vibrant and captivating metropolis. It is the only city that looks out over the sea yet begins in the Andes. 5000 years of history Spanish 0-5000 meters 19.4º founding: meters average 18 January 1535 9 886 647 154 Lima has inhabitants average elevation temperature (INEI, 2015) nd 2 Highest ranked in Latin America (2016) 18 848 207 passengers 176 865 aircraft Every Lima Politically, Lima 27 refers to a region, a airlines province, a city: Metropolitan + Info: lima-airport.com Lima, and a district. -

Hidden Mysteries of Peru

Peru HIDDEN MYSTERIES OF PERU 13 Days FROM $3,389 Ancient Inca Circular Terraces in Moray Puno HOSTED PROGRAM PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS (2) Lima • (2) Puerto Maldonado • (3) Sacred Valley • (2) Cusco • (2) Puno • (1) Paracas •Stay in an authentic lodge and have amazing ecological adventures in Puerto Maldonado •Have the experience of a lifetime exploring the lost city of the Incas – Machu Picchu, Peru’s most important archeological site and one of the new Seven Wonders of the World ECUADOR •Explore Cusco’s Koricancha Temple and Sacsayhuaman Fortress •Get to know pre-Inca culture at Taquile Island, 12,000 feet above sea level PERU BRAZIL •Sail to the famous Uros Islands, man-made floating islands in the middle of Lake Titicaca National Reserve Lima 2 Machu Picchu •See the mysterious Nazca lines on a flight over 2 Puerto Maldonado Sacred Valley 3 the enormous outlines of stylized plants, animals, 2 Cusco and shapes scattered on the desert floor that has Paracas 1 remained undisturbed for 2000 years Puno 2 DAY 1 I LIMA Arrive in Lima and transfer to your hotel. Afternoon is at leisure. DAYS 2 – 3 I LIMA I PUERTO MALDONADO Private transfer to Lima airport to board your flight to Puerto Maldonado. Upon arrival, # - No. of Overnight Stays Arrangements by transfer to your lodge. For the next two days, enjoy activities including: DAY 12 I LIMA I PARACAS I NAZCA LINES Early transfer to the bus Concepcion Rainforest Trails, Twilight Canoe Cruise on Madre de Dios station to board your bus to Paracas. Upon arrival in Paracas transfer to HIDDEN MYSTERIES OF PERU River, Lake Sandoval hike, Inkaterra Canopy Walkway over 7 treetop your hotel. -

South America's Ancient Civilizations

SIGMAXTHE SCIENTIFICI EXPEDITIONS RESEARCH SOCIETY BETCHART EXPEDITIONS Inc. 17050 Montebello Road, Cupertino, CA 95014-5435 ============================================ South America’s Ancient Civilizations A Voyage to Sacred Sites and Ceremonial Centers Aboard the 50-Suite Clelia II October 17 – November 2, 2009 ============================================ ONCE-IN-A- LIFETIME OPPORTUNITY! UNPRECEDENTED SAVINGS Thursday, October 22 SALAVERRY | EL BRUJO o r TRUJILLO | SALAVERRY Visit El Brujo Archaeological Complex and the newly opened Museo de Cao or tour Trujillo, founded by the Spanish in 1534 and known for its colonial archi- tecture. Friday, October 23 CALLAO | LIMA | CALLAO Spend the day in Lima, Peru’s capital, founded in 1535. Visit the historical city center, the National Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, and the Gold Museum, a private collection of pre-Columbian treasures. Saturday, October 24 CALLAO | PACHACÁMAC | PURUCHUCO | CALLAO Before the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century, the area around Lima contained vibrant cities. Explore two that predate the Spanish conquest: Pachacámac, a vast complex of palaces, pyramids, and buildings, and Puruchuco, the palace of a local nobleman. Sunday, October 25 Quito, Ecuador SAN MARTIN | PARACAS | BALLESTAS ISLANDS | SAN MARTIN THIS autumn, JOIN US ON A voyage Explore the Paracas peninsula, a reserve Itinerary protecting an important marine eco- to SOUTH AMERICA FROM THE COL- system. Paracas was also a pre-Nazca Saturday, October 17, 2009 ORFUL CITIES OF Ecuador to THE DEPART USA necropolis, with over 400 mummies MAGNIFICENT SHORES OF CHILE. excavated. Also discover the Ballestas On Sunday, October 18 Islands, home to thousands of seabirds. QUITO, Ec u a d o r this voyage you’ll discover sublime examples of Monday, October 26 Spanish colonial architecture in Quito, Ecua- Transfer to Hilton Colon Quito Hotel. -

Nazca Week 06 Lecture 02 the Mysterious Lines and Geoglyphs in Southern Peru

Montclair State University Department of Anthropology Anth 140: Non Western Contributions to the Western World Dr. Richard W. Franke Nazca Week 06 Lecture 02 The Mysterious Lines and Geoglyphs in Southern Peru This lecture was last updated on 15 March 2013 and 10 September, 2019 1 Montclair State University Department of Anthropology Anth 140: Non Western Contributions to the Western World Dr. Richard W. Franke The Lines at Nazca The learning objectives for week 06 lecture 02 are: – to learn a few of the achievements of the Incas and pre-Inca peoples of the Andes – to understand how archaeologists and other scientists reconstruct the past and how they come to improved conclusions with better information 2 Montclair State University Department of Anthropology Anth 140: Non Western Contributions to the Western World Dr. Richard W. Franke The Lines at Nazca Terms you should know for week 06, the topic of Nasca are: – Nazca – also spelled Nasca 3 Montclair State University Department of Anthropology Anth 140: Non Western Contributions to the Western World: Dr. Richard W. Franke The Lines at Nazca Week 06 Sources on Nazca: Aveni, Anthony. 2000. Nasca: Eighth Wonder of the World? London: British Museum Press. Hall, Stephen S. 2010. Spirits in the Sand: The Ancient Nasca lines of Peru Shed their Secrets. National Geographic March 2010. Lansing, J. Stephen. 1993. Priests and Programmers: Technologies of Power in the Engineered Landscape of Bali. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Moseley, Michael E. 1992. The Incas and Their Ancestors: The Archaeology of Peru. London. Thames and Hudson. Pages 187-190; This slide was updated 14 4 March 2013 Montclair State University Department of Anthropology Anth 140: Non Western Contributions to the Western World Dr. -

Two Paths to Populism: Explaining Peru's First Episode of Populist

Two Paths to Populism: Explaining Peru’s First Episode of 1 Populist Mobilization Robert S. Jansen Ph.D. Candidate Department of Sociology University of California, Los Angeles http://rjansen.bol.ucla.edu/ [email protected] ***DRAFT*** Please do not cite without requesting a more recent version from the author. ABSTRACT: Both major contenders in Peru’s 1931 presidential contest made populist mobilization a centerpiece of their political strategies. Never before had a candidate for national office so completely flouted traditional channels of political power and so thoroughly staked his political aspirations on the mobilization of support from non-elite segments of the population. This paper asks: Why did these two candidates pursue novel populist strategies at this particular historical juncture? The first part of the paper identifies the conditions that encouraged Peruvian politicians to pursue populist mobilization in 1931; it also explains why populist mobilization had never before been undertaken in Peru. An adequate explanation of populist mobilization, however, must also trace the social processes by which objective conditions translate into the selection of specific lines of action by political leaders. The second part of this paper thus assesses the socially-conditioned strategic vision of the various political actors operating in 1931. Only by adding this second step to the inquiry is it possible to answer the question of why, if all encountered the same objective conditions, some actors in the political field pursued populist strategies while others did not. Ultimately, I identify two paths to populist mobilization: an ideological route and an accidental route. Other political actors chose not to pursue populist mobilization for one of two reasons: some saw it as going too far in undermining the elite bases of the traditional political structure; others saw it as not going far enough toward fostering revolutionary change.