Emerging Tourism in Peru by Jeffrey S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gestión Del Patrimonio Cultural De La Zona Arqueológica De Huaycán Y

http://dx.doi.org/10.36097/rsan.v1i38.1132 Artículo original Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Zona Arqueológica de Huaycán y su impacto en el Desarrollo Turístico Cultural Heritage Management of the Archaeological Zone of Huaycán and its impact on Tourism Development Autora Iris Mariela Donayre Pérez. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7860-3977 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Perú. [email protected] Resumen La zona arqueológica de Huaycán de Pariachi del distrito ATE, fue declarada Monumento del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación, a la fecha se conoce poco sobre el desarrollo de esta zona desde el punto de vista turístico, motivo por el cual el presente estudio tiene como objetivo: conocer el impacto de la gestión del patrimonio cultural en el desarrollo turístico de la zona. La investigación es descriptiva, con un diseño no experimental trasversal, con un muestreo no probabilístico aleatorio simple, quedando representado la muestra por 132 personas, a quienes se les aplico técnicas cualitativas y cuantitativa, se utilizó como técnica cualitativa la entrevista a profundidad semi estructurada y la técnica cuantitativa la encuesta, ambos instrumentos se validaron en contenido bajo juicio de expertos, y el cuestionario se le aplicó la confiabilidad del alfa de Cronbach, mediante el programa estadístico SPSS V23. Obteniendo como resultado un nivel de impacto bajo en la gestión del patrimonio cultural en el desarrollo turístico de la zona arqueológica de Huaycán de Pariachi. Además de un nivel de significancia bajo indicando que no hay relación entre las variables. Por lo que es necesario ejecutar mejoras en la gestión del patrimonio cultural para el desarrollo turístico. -

Tourism in Peru: Economic Benefits at the Cost of Cultural Loss (2018)

Seattle University ScholarWorks @ SeattleU International Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses International Studies 2018 Tourism in Peru: Economic Benefits at the Cost of Cultural Loss (2018) Doni Uyeno Seattle University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/intl-std-theses Recommended Citation Uyeno, Doni, "Tourism in Peru: Economic Benefits at the Cost of Cultural Loss (2018)" (2018). International Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses. 25. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/intl-std-theses/25 This Latin America is brought to you for free and open access by the International Studies at ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ SeattleU. Seattle University Tourism in Peru: Economic Benefits at the Cost of Cultural Loss A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Departmental Honors in International Studies By Doni Uyeno June 2018 Uyeno, Doni Tourism in Peru: Economic Benefits at the Cost of Cultural Loss 3 Abstract This thesis attempts to evaluate and understand what makes tourism unsustainable within the Sacred Valley of Peru. It challenges the traditional way of measuring the impacts of tourism through its economic benefits and instead measures the impacts of tourism through its contributions to cultural loss. This thesis starts with an understanding of the impacts of tourism in a global context, followed by a case study focusing specifically on tourism in the Sacred Valley of Peru. The critical evaluation of tourism leads to the conclusion that tourism needs to be monitored and evaluated through processes that take cultural loss into consideration while centering the voices of the communities that are being negatively impacted by tourism. -

Generic Viagra Discussion Forum

______________________________________________________________ USIL INTERNATIONAL CUSCO Study & Research Programs _____________________________________________________________ https://www.facebook.com/International.CUSCO/ 1 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ INDEX _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WELCOME TO CUSCO! . HISTORY OF LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA OUR INTERNATIONAL STUDY PROGRAM . INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION o ABOUT OUR CENTER . COMMUNICATION PSYCHOLOGY o SEMESTERS & SUMMER TERMS o BUSINESS o USIL HANDS-ON COMPONENT . BUSINESS IN PERU AND LATIN AMERICA o OUR FIELD TRIPS . INTERNATIONAL TRADE: IMPORT AND EXPORT o VISITING MACHU PICCHU AND THE SACRED VALLEY OF THE INCAS o ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES OUR COURSES . PERU’S BIODIVERSITY o LANGUAGES o HEALTH AND NUTRITION . ADVANCED SPANISH . HEALING AND SHAMANISM IN ANDEAN AND AMAZONIAN CULTURES . INTERMEDIATE SPANISH . ANDEAN NUTRITION . PRE-INTERMEDIATE SPANISH o TOURISM . BEGINNING SPANISH . ECONOMICS AND SOCIOLOGY OF TOURISM . WRITTEN COMMUNICATION IN SPANISH . CULTURAL TOURISM IN CUSCO AND PERU . BEGINNING QUECHUA . PARTICIPATORY AND IMMERSION TOURISM IN PERU o HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES . SUSTAINABLE TOURISM . CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY AND CULTURE OF PERU o GASTRONOMY . HISTORY AND CULTURE OF THE INCAS . HISTORY OF PERUVIAN CUISINE . INSTITUTIONS IN PERUVIAN SOCIETY . GASTRONOMIC TOURISM IN CUSCO AND PERU -

7. Northern Peru 8

CONTENTS 1. Summary of tourism in Peru including UK visitor statistics 2. Tourism news ➢ Destination news ➢ Sport tourism news ➢ Gastronomy news ➢ Transport news ➢ Tour operator updates ➢ Hotel developments 3. Peru’s calendar of events 4. Rural, community and ecotourism in Peru 5. Trekking in Peru – follow in the footsteps of the Incas and beyond 6. Peruvian Amazon – Things to know and what to do 7. Northern Peru 8. Southern Peru 9. Gastronomy 10. Birdwatching and wildlife 11. Adventure activities from trekking to white water rafting 12. Peru tourism fact sheet 1. SUMMARY OF TOURISM IN PERU AND UK VISITORS STATISTICS Peru has seen landmark tourism developments in recent years, including the inauguration of the long-awaited Kuelap Cable Car, opening up access to northern Peru’s celebrated pre-Inca city, the launch of South America’s first luxury sleeper train, the Belmond Andean Explorer, and a number of new international and domestic flight routes boosting connectivity from the UK into Peru, and between the north and south of the country. While Lima, Cusco and Machu Picchu remain high on the bucket lists of international travellers, in the past few years Peru’s north has been in the spotlight after being effectively promoted as an undiscovered alternative to Peru’s popular southern tourism circuit. Peru is now celebrating Lonely Planet having recently named Northern Peru, including the ancient fortress of Kuelap and the Chachapoyas region, as a must-visit destination in its renowned Best in Travel ‘Top 10 Regions’ 2019 list. Peru’s reputation as a leading responsible tourism destination has continued to gain momentum throughout 2018. -

Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru. Sippo.Ch Welcome

Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru. sippo.ch Welcome. The Andes, which originate in Patagonia and extend over seven thousand kilometers in South America, have shaped a variety of landscapes, peoples and cultures. Amidst the Andes, Peru is the repository of immeasurable wealth, both tangible and intangible. Icons and “Unique Selling Positions” are Machu Picchu and the mystical city of Cusco, the birthplace of the Inca Empire. But the country offers a lot more to visitors. Our vision is to expand tourism destinations in Peru beyond Machu Picchu to give greater value to the country‘s rich cultural heritage, its abundant biodiversity and world-class gastronomy. The State Secretary for Economic Affairs SECO has been sup- porting sustainable tourism in Peru since 2003, together with two strategic Swiss partners. In cooperation with Swisscontact, SECO promotes the concept of Destination Management Organi- sations (DMOs), which represents a dynamic platform where public and private actors jointly position their regional tourist des- tinations in the international market. This project has led to the establishment of six DMOs in Southern Peru as well as one covering the north of the country. SECO is also financing the Swiss Import Promotion Programme SIPPO which assists leading SMEs with a clear focus on quality and sustainability in their efforts to market their touristic offers internationally. The Branch Overview on Sustainable Tourism in Peru is a useful milestone in these efforts, providing Swiss tourism business partners and consumers with suitable products in Peru. I wish all readers of the Branch Overview a successful reading and Disclaimer can promise them that SECO will continue to work towards the The information provided in this publication is believed to be ac- growth of tourism in Peru for the benefit of both the Peruvian and curate at the time of writing. -

Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru

AC 2011-2240: MATHEMATICS AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE INCAS IN PERU Cheri Shakiban, University of St. Thomas I am a professor of mathematics at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I have been a faculty member since 1983. I received my Ph.D. in 1979 from Brown University in Formal Cal- culus of Variations. My recent area of research is mostly in computer vision, with applications to object recognition. My publications are in diverse areas of mathematics and engineering. I love to work with undergraduate students, in particular, underrepresented students, to get them involved in doing research in mathematics and encourage them to give conference presentations/posters and submit their work for publication. In addition to teaching regular math courses, I also like to create and teach innovative courses such as ”Mathematical symmetry of Southern Spain” and ”Mathematics and Architecture of the Incas in Peru”, which I have taught as study abroad courses several times. Michael P. Hennessey, University of St. Thomas Michael P. Hennessey (Mike) joined the full-time faculty as an Assistant Professor fall semester 2000. He is an expert in machine design, computer-aided-engineering, and in the kinematics, dynamics, and control of mechanical systems, along with related areas of applied mathematics. Presently, he has published 41 technical papers (published or accepted), in journals (9), conferences (31), or magazines (1). In 2006 he was tenured and promoted to the rank of Associate Professor. Mike gained 10 years of industrial and academic research lab experience at 3M, FMC, and the University of Minnesota prior to embarking on an academic career at Rochester Institute of Technology (3 years) and Minnesota State University, Mankato (2 years). -

CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26

Arrive: 0800 Tuesday November 22 CALLAO, PERU Onboard: 1800 Saturday November 26 Brief Overview: A traveler’s paradise, the warm arms of Peru envelope some of the world’s most timeless traditions and greatest ancient treasures! From its immense biodiversity, the breathtaking beauty of the Andes Mountains (the longest in the world!) and the Sacred Valley, to relics of the Incan Empire, like Machu Picchu, and the rich cultural diversity that populates the country today – Peru has an experience for everyone. Located in the Lima Metropolitan Area, the port of Callao is just a stone’s throw away from the dazzling sights and sounds of Peru’s capital and largest city, Lima. With its colorful buildings teeming with colonial architecture and verdant coastline cliffs, this vibrant city makes for a home-away-from-home during your port stay in Peru. Nearby: Explore Lima’s most iconic neighborhoods - Miraflores and Barranco – by foot, bike (PER 104-201 Biking Lima), and even Segway (PER 121-101 Lima by Segway). Be sure to hit up one of the local markets (PER 114-201 Culinary Lima) and try out Peruvian fare – you can’t go wrong with picarones (fried pumpkin dough with anis seeds and honey - pictured above), cuy (guinea pig), or huge ears of roast corn! Worth the travel: Cusco, the former capital of Incan civilization, is a short flight from Lima. From this ancient city, you can access a multitude of Andean wonders. Explore the ruins of the famed Machu Picchu, the city of Ollantaytambo – which still thrives to this day, Lake Titcaca and its many islands, and the culture of the Quechua people. -

Catálogo Cusco Cambios 2017-2 (3).Pdf

We invite you to study while enjoying a unique cultural immersion experience in the most important historic city in South America, the former capital of the Inca Empire, and visiting one of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Inca royal residence of Machu Picchu. Cusco is situated in the heart of the Andes, at an altitude of 3400 meters (11,300 feet). It is a city in which ancient Inca royal palaces and temples share space with colonial-era Spanish mansions and beautifully decorated churches. Today, Cusco is a melting pot of cultures with a richly cosmopolitan feel, where ancient indigenous traditions and customs are overlaid with the trappings of the modern world. Every year, millions of tourists come to Cusco to see Machu Picchu, the legendary Inca settlement nestled among mountains covered in tropical forest, just four hours from Cusco by bus and train. Over the past one hundred years, Machu Picchu has emerged as one of the most emblematic sites on the continent, and a must-see experience for travelers interested in history and culture. The Cusco region boasts a series of spectacular landscapes, from the high peaks of the Andes, which give way to the foothills surrounding the city itself, to the forests of the Amazon basin, with their breathtaking variety of plant and animal species. The people of Cusco are open, forthcoming and always willing to give a warm welcome to visitors. We take pleasure in sharing these treasures with you. Communication Introduction to Communication Communication for Development History of Latin American Cinema -

Viewees Who Donated Their Time and Knowledge to the Dissertation Research

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Selling Sacred Cities: Tourism, Region, and Nation in Cusco, Peru A Dissertation Presented by Mark Charles Rice to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Mark Rice 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Mark Charles Rice We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Paul Gootenberg – Dissertation Advisor SUNY Distinguished Professor, History, Stony Brook University Eric Zolov – Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, History, Stony Brook University Brooke Larson Professor, History, Stony Brook University Deborah Poole Professor, Anthropology, Johns Hopkins University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Selling Sacred Cities: Tourism, Region, and Nation in Cusco, Peru by Mark Charles Rice Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2014 It is hard to imagine a more iconic representation of Peru than the Inca archeological complex of Machu Picchu located in the Cusco region. However, when US explorer, Hiram Bingham, announced that he had discovered the “lost city” in 1911, few would have predicted Machu Picchu’s rise to fame during the twentieth century. My dissertation traces the unlikely transformation of Machu Picchu into its present-day role as a modern tourism destination and a representation of Peruvian national identity. -

Tourism and the Community: Direction, Purpose and Challenges in Caribbean Tourism

TOURISM AND THE COMMUNITY: DIRECTION, PURPOSE AND CHALLENGES IN CARIBBEAN TOURISM BY Chandana Jayawardena ABSTRACT In the Caribbean, communities are often left out of tourism development and planning which results in resentment and negative actions against the industry such as visitor harassment. A number of countries have therefore, demonstrated initiatives geared to include local communities in the tourism industry by ensuring that they have meaningfkl participation. This paper examines the dL,namics of the tourism sector and the community, and the relationship that may exist between the two. 7he author also categorises various levels of community involvement in tourism. Two models are presented to demonstrate the importance of community in the tourism experience. Khe author then redefines the term "community" in the context of the tourism sector and discusses community tourism and its implications for sustainable tourism development. Suggestions and recommendations are made for the inclusion of communities in the tourism sector. INTRODUCTION Tourism was not a planned strategic option in most Caribbean countries. The industry is at times faced with challenges such as crime and tourist harassment. The need for planned sustainable development is, therefore, essential for the fbture of tourism in the Caribbean. Efforts have been made by countries such as Belize, Dominica and Guyana to develop alternative forms of tourism such as eco-tourism, agro-tourism and community tourism to address concerns that have arisen as a result of conventional mass tourism activities. This paper begins with an examination of tourism within the Caribbean. A new model - Pyramid of Tourism Segmentation POTS) - is explained and the development of special interest tourism is advocated. -

On the Road CAROLINA a MIRANDA Coordinating Author on This Assignment, I Literally Ate My Way Through Lima

© Lonely Planet 4 On the Road CAROLINA A MIRANDA Coordinating Author On this assignment, I literally ate my way through Lima. This gobble-fest was with a friend at a popular chifa (Chinese restaurant) in Barranco (p115 ). After carbo-loading on wontons, langostino fried rice and steamy piles of noodles, we were ready to destroy our livers at the neighborhood’s many – and I mean many – bars. AIMÉE DOWL Southern Peru’s archaeological riches get top billing, but northern Peru’s mysterious ruins – mist-shrouded temples, haunting hilltop sarco- phagi and mummies, mummies everywhere! – turned on the amateur archaeologist in me. My guide at Chavín de Huántar (p422 ) explained details about spine-chilling carvings that brought this ancient world to life. KATY SHORTHOUSE Some bears and me in a village between BETH WILLIAMS That claw pro- Cuzco and Puno (p288 ). My truding from the bottom of this intrepid traveling companion photo belongs to the enormous Steve Wilson and I hit the chupe de camarones (shrimp area as the sun went down, chowder) I devoured after a trek stumbling straight into a huge in the Cañón del Colca ( p187 ). fiesta. The only gringos for It was well earned after a night miles around, we ended up spent in a leaky thatched hut at with places of honor at the the base of the canyon – and postparade festivities. they said rainy season was over! LUKE WATERSON I’d been stranded for two days in the remote town of Pevas (p507 ), located on an Amazon tributary. No boats were headed back to civiliza- tion, so I hitched a lift on this raft. -

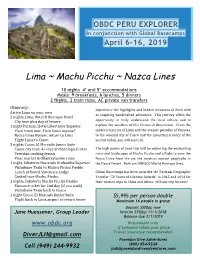

Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines

OBDC PERU EXPLORER In conjunction with Global Basecamps April 6-16, 2019 Lima ~ Machu Picchu ~ Nazca Lines 10 nights 4* and 5* accommodations Meals: 9 breakfasts, 6 lunches, 5 dinners 2 flights, 2 train rides, AC private van transfers Itinerary: Experience the highlights and hidden treasures of Peru with Arrive Lima on your own an inspiring handcrafted adventure. This journey offers the 2 nights Lima, Hotel B Boutique Hotel City tour plus day of leisure opportunity to truly understand the local culture and to 1 night Paracas, Hotel LiBertador Superior explore the wonders of this historical destination. From the Pisco town tour, Pisco Sours anyone? modern luxuries of Lima and the seaside paradise of Paracas, Nazca Lines flyover, return to Lima to the colonial city of Cusco and the mountain scenery of the Flight Lima to Cusco Sacred Valley, you will see it all. 3 nights Cusco, El Mercado Junior Suite Cusco city tour, 4+ Inca archaeological sites The high points of your trip will Be exploring the enchanting Peruvian cooking lesson ruins and landscapes of Machu Picchu and a flight to view the Pisac market & OllantaytamBo ruins Nazca Lines from the air, the mystical ancient geoglyphs in 1 night, Inkaterra Hacienda UruBamBa Superior the Nazca Desert. Both are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Vistadome Train to Machu Picchu PueBlo Lunch at famed Sanctuary Lodge GloBal Basecamps has Been awarded the National Geographic Guided tour Machu Picchu Traveler “50 Tours of Lifetime Awards” in 2015 and 2014 for 2 nights, Inkaterra Machu Picchu PueBlo their custom trips to China and Africa.