Rings and Pulses: the Route to Regenerating the Jerusalem Neighborhood of Kiryat Yovel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arkitektur I Konflikt

Arkitektur i konflikt: Arkitekturens rolle i kampen om Jerusalem Ida Kathinka Skolseg MØNA4590 - Masteroppgave i Midtøsten- og Nord-Afrika-studier Institutt for kulturstudier og orientalske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Mai 2016 II The city does not consist of this, but of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past… The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment mamrked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. III © Forfatter Ida Kathinka Skolseg År 2016 Tittel Arkitektur i konflikt: Hva er arkitekturens rolle i kampen om Jerusalem Forfatter Ida Kathinka Skolseg http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Sammendrag Israel forsøker å presentere Jerusalem som en forent by, hvis udelelige egenskap er basert på Jerusalems rolle som jødenes religiøse, historiske og politiske hovedstad. Den politiske dimensjonen av "å bygge landet Israel" er en fundamental, men samtidig en skjult komponent av enhver bygning som blir konstruert. Den politiske virkeligheten dette skaper er ofte mer konkluderende og dominerende enn hva den stilmessige, estetiske og sensuelle effekten av hva en bygning kan kommunisere. "Ingen er fullstendig fri fra striden om rom", skriver Edward Said, "og det handler ikke bare om soldater og våpen, men også ideer, former, bilder og forestillinger." 27. juni, to uker etter at Seksdagerskrigen endte i 1967, ble 64 kvadratkilometer land og ca. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

Exporting Zionism

Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Ayala Levin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Exporting Zionism: Architectural Modernism in Israeli-African Technical Cooperation, 1958-1973 Ayala Levin This dissertation explores Israeli architectural and construction aid in the 1960s – “the African decade” – when the majority of sub-Saharan African states gained independence from colonial rule. In the Cold War competition over development, Israel distinguished its aid by alleging a postcolonial status, similar geography, and a shared history of racial oppression to alleviate fears of neocolonial infiltration. I critically examine how Israel presented itself as a model for rapid development more applicable to African states than the West, and how the architects negotiated their professional practice in relation to the Israeli Foreign Ministry agendas, the African commissioners' expectations, and the international disciplinary discourse on modern architecture. I argue that while architectural modernism was promoted in the West as the International Style, Israeli architects translated it to the African context by imbuing it with nation-building qualities such as national cohesion, labor mobilization, skill acquisition and population dispersal. Based on their labor-Zionism settler-colonial experience, -

Israeli Sources for Researching Sephardic Jewry in the Holocaust Prof. Yitzchak Kerem Po Box 10642, Jerusalem 91102 Tels

Israeli Sources for Researching Sephardic Jewry in the Holocaust Prof. Yitzchak Kerem Po Box 10642, Jerusalem 91102 Tels: 02-5795595, 054-4870316 FAX: 972-2-5337459 [email protected] http://www.sephardicmuseum.org Genealogical Sources on Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews in the Holocaust Located in Jerusalem and elsewhere in Israel By Prof. Yitzchak Kerem, Foundation for Jewish Diversity and Habayit Lemoreshet Kehilot Sefarad vehaMizrah Archives Yad Vashem Interviews, Spielberg interviews, name lists, archival documents, Red Cross Tracing Service Database Mauthausen card index, Righteous Gentile department files, Jerusalem Municipal Archives, Basement of the Jerusalem Municipality, Jerusalem Sephardic Council files and correspondences Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People, Givat Ram, Collection on Greece until 1941, annotates life of those later annihilated by the Nazis in 1943-44. Collectiion on Yugoslavia Collection on Bulgaria donated by the Bulgarian Immigrants Association Joint Distribution Committee Archives, 12 Beit Hadfus, Givat Shaul Numerous files on refugees from Greece to Turkey, Portugal, and after WWII Israel State Archive, 14 Hartom, Rad Building, First Floor, Har Hotzvim, Jerusalem Many files on the Mufti in Bosnia, Eichmann Trial, and Reaction of Jewish Yishuv in Eretz-Israel to Holocaust. Libraries National Library, Givat Ram, Genealogy Section, Judaica Reading Room Yad Ben Zvi, 12 Abravanel Street, Rehavia, numerous sections on Greece, Yugoslavia, Morocco, Tunisia, Italy Center for the Heritage of North African Jewry, King David Street By appointment Books Haim Asitz, Yitzchak Kerem, Menachem Persof, and Steve Israel, eds. The Shoa in the Sephardic Communities (Jerusalem; Sephardic Educational Center, 2006). Irit Bleigh, ed. Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Tunisia and Libya (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1997).[Hebrew] Eyal Ginio, ed. -

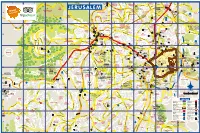

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E . -

The Knesset Building in Giv'at Ram: Planning and Construction

The Knesset Building in Giv’at Ram: Planning and Construction Originally published in Cathedra Magazine, 96th Edition, July 2000 Written by Dr. Susan Hattis Rolef Introduction Already in the early days of modern Zionism, it was clear to those who envisioned the establishment of a Jewish State, and those who acted to realize the vision, that once it was established, it would be a democracy, in which a parliament would be built. In his book Altneuland (written in 1902), Theodor Herzl, described the parliament of the Jewish state in Jerusalem in the following words: “[A] great crowd was massed before (the Congress House). The election was to take place in the lofty council chamber built of solid marble and lighted from above through matte glass. The auditorium seats were still empty, because the delegates were still in the lobbies and committee rooms, engaged in exceedingly hot discussion…" 1 In his book Yerushalayim Habnuya (written in 1918), Boris Schatz, who had established the Bezalel school of arts and crafts, placed the parliament of the Jewish State on Mount Olives: "Mount Olives ceased to be a mountain of the dead… it is now the mountain of life…the round building close to [the Hall of Peace] is our parliament, in which the Sanhedrin sits".2 When in the 1920s the German born architect, Richard Kaufmann, presented to the British authorities his plan for the Talpiot neighborhood, that was designed to be a Jerusalem garden neighborhood, it included an unidentified building of large dimensions. When he was asked about the meaning of the building he relied in German: "this is our parliament building". -

Near East University Docs

NEAR EAST UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES ARCHITECTURE AND POLITICS: The Use of Architecture as a Language of War in The Case of Jerusalem City Rami Mushasha Master Thesis Department of Architecture Nicosia-2008 2 Rami Mushasha: Architecture and Politics Architecture in Jerusalem during Israeli Occupation Approval of Director of the Institute of Social and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. ilkay Salihoğlu Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Oleg Nikitenko We certify that this thesis is satisfactory for the award of the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Examining Committee in Charge: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Oleg Nikitenko Dr. Ayten Ozsavas Akcay Dr. Huriye Gurdalli 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First, I would like to thank my supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Oleg Nikitenko for his invaluable advice and belief in my work through the course of my master degree. Great thanks to my parents Fouad and Ekram Mushasha for their constant support and encouragement all the time. Special thank to the staff of Architecture Department in Near East University for their great support to me from the first day for me in the university. Finally, I would like to thank all my friends for their advice and support. 4 ABSTRACT Architecture always played an important role in the formation of societies, giving us an explanation of the life style of various nations. In the case of Jerusalem, all through the past century, in parallel to politics and economy architecture had a great influence in changing the identity and nature of Jerusalem architecture, putting it to use in achieving political goals there, which consequently made it synonymous to language of war. -

The National Library of Israel Master Plan for Renewal 2010–2016

THE NATIONAL MASTER PLAN FOR RENEWAL 2010–2016 LIBRARY OF ISRAEL Fall 2010 THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF ISRAEL MASTER PLAN FOR RENEWAL 2010–2016 Fall 2010 0($(S&=H &0(&JNQ&0WX#& THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF ISRAEL Mishneh Torah TABLE OF CONTENTS , Maimonides, Spain, 14th century PREFACE 4 פרק INTRODUCTION 6 פרק THE CONCEPT OF LIBRARY RENEWAL 10 The Information Revolution and the National Library 10 The National Library in the Year 2020 10 Library Collections 12 Judaica Collection 13 Israel Collection 14 Islam and Middle East Collection 15 General Humanities Collection 16 Expanding the Collection through Collaboration 16 An Institution for Research and Study 16 A Centre of Culture and Education 17 Cultural Activities 17 Educational Programmes 18 A Hybrid Physical–Digital Library 18 A New Physical Infrastructure 20 Funding Sources 21 פרק LIBRARY GOALS FOR 2010–2016 24 Collection Development 26 Research and Reference Services 28 Cultural and Educational Centre 30 Digital Library 32 Collaborative Relationships 34 Work Processes 36 Preservation of Collections 38 Adaptation 40 Integration of Technology 42 Public Standing and Legal Status 44 Financial Sustainability 46 New Building Construction 48 Ongoing Activity in the Current Building 50 פרק APPENDICES 52 PREFACE The National Library of Israel is experiencing a surge of renewal, aimed the public’s horizons and encourage familiarity with other cultures and at making it a central and active player in the cultural and intellectual ideas from the very finest sources of information. life of all citizens of the State of Israel, of Diaspora Jewry and of the general public worldwide. The plan presented in this booklet The implementation of the renewal plan and the Library’s relocation focuses on practical steps, providing a detailed description of the to an appropriate, accessible and friendly building will enable renewal process, as well as addressing the main objectives and values the realization of these aspirations. -

Changes and Improvements to Bus Lines

From - 21.2.2014 The New Transportation Network in Jerusalem Changes and Improvements to Bus Lines Pamphlet Pisgat Ze’ev | Neve Yaakov | The French Hill | Har Hatzofim Givat Ram | Gonenim | Givat HaMatos | Moshavot | Malcha Givat Mordechai | Bet HaKerem | Kiryat Moshe | Bayit VeGan Ramat Sharet | Givat Shaul Industrial Zone | Talpiot Industrial Zone Public transportation in Jerusalem continues to make progress towards providing faster, more efficient and better service Dear passengers, On 21.2.14 the routes of several lines operating in Jerusalem will be changed as part of the continuous improvement of the city’s public transportation system. Great emphasis was put on improving the service and accessibility to the city’s central employment areas: Talpiot, Givat Shaul, the Technological Garden, Malcha and the Government Complex. From now on there will be more lines that will lead you more frequently and comfortably to and from work. The planning of the new lines is a result of cooperation between the Ministry of Transport, the Jerusalem Municipality and public representatives, through the Jerusalem Transport Master Plan team (JTMT). This pamphlet provides, for your convenience, all the information concerning the lines included in this phase: before you is a layout of the new and improved lines, station locations and line changes on the way to your destination. We wish to thank the public representatives who assisted in the planning of the new routes, and to you, the passengers, for your patience and cooperation during the implementation -

Guide for the New and Visiting Faculty

GUIDE FOR THE NEW AND FOR VISITING FACULTY GUIDE FOR THE NEW AND VISITING FACULTY Twelfth Edition The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Guide For The New And Visiting Faculty CONTENTS | 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 The Pscyho-Educational Service 65 Health Services in Schools 65 CHAPTER ONE English for English Speakers 65 THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM 4 Extracurricular Activities 66 The Adviser’s Office 4 Sports 66 Introduction to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem 5 Music and Art 66 The Edmond J. Safra (Givat Ram) Campus 6 Other Activities 67 The Ein Kerem Campus 7 Community Centers 67 The Rehovot Campus 7 Youth Movements 67 Libraries 8 Field Schools 68 Other University Units 12 Summer, Hanukkah and Passover Camps 68 The Rothberg International School 15 CHAPTER SIX International Degree Programs 18 UNIVERSITY, ADULT, AND CONTINUING EDUCATION 70 Non-Degree Graduate Programs 19 Academic Year 21 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 70 Adult Education 71 CHAPTER TWO Hebrew Language Studies 72 FACILITIES ON CAMPUS 22 CHAPTER SEVEN Getting There 22 GETTING TO KNOW JERUSALEM: LIFESTYLE AND CULTURE 73 Security: Entry to Campus 24 Administration 26 General Information 73 Traditional and Religious Activities 30 Leisure Time 74 Academon 32 Touring Jerusalem 74 Performing Arts 76 CHAPTER THREE Cafés, Bars and Discotheques 76 PLANNING TO COME 40 Cinema 76 Visa Information 40 Media 77 Salaries and Taxes 42 Museums 78 Income Tax 42 Libraries 81 Value Added Tax (VAT/“ma’am”) 43 CHAPTER EIGHT National Insurance (Bituah Leumi) 43 OUT AND ABOUT IN JERUSALEM 82 -

JERUSALEM's CAPITAL HILL New Year Greetings

., , , ..' ., •• • . '. " , ,. ~.'" . , ~.-> ,,'- .-- • r',\',."" "";' ,,'., ,,-' ~' .. ..... ~",-,' ' -- ... • __ • '. J ..... _._ ....".',." .. ,.•. Thursday, September Zl, 1962 . THE JEWISH POST Thursday, September Zl, i962 THI: JEWISH POST Page One Hundred end .Five' Page One Hundred end Four stantly deferred, that the terms of of Israel has started to build on its three ministries, of one' pattern, BEST WISHES FOR A HAPPY NEW YEAR the armistice agreement would be section of the Hill. It has completed functional and undeCorated, but JERUSALEM'S CAPITAL HILL • TO MY MANY PATRONS AND FRIENDS fulfilled, and the university would 17"'======"""==""';='=:-1 possessing a certain beauty of de- New Year Greetings resume its cultural work in its Joyous New Year Greetings sign, because they catch the rhythm Outside the historic limits of the By NORMAN BENTWICH home. to all our Jewish Patrons 1of the slope. On the peak of the Holy City, with its three "moun- Best Wishes for a Happy New Year to all our The teaching and research were and Friends Capitol ,the single-chamber House tains," Moriah, Zion, and Ophel, it· * * " . carried on provisionally in scattered HAIR FASHIONS of Parliament (the Knesset) is ris- --." SRAEL'S Jerusalem today, like ancient Rome, has its Capitol Hill, which is in the south-west sector of the • .-, , Jewish Patrons and Friends , I _ and . improvised premises in tlie ing, and will' replace the austere is to be both the civic and the academic centre of Israel. Its name in New ,City, separated and screened , ' I I Jewish sector of the town. In 1953 .building on King George. Avenue, Hebrew is Givat Ram, which means literally "the Exalted Height." Exten~- from the modern resldential quarter , by .