The Upper Kidron Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Arkitektur I Konflikt

Arkitektur i konflikt: Arkitekturens rolle i kampen om Jerusalem Ida Kathinka Skolseg MØNA4590 - Masteroppgave i Midtøsten- og Nord-Afrika-studier Institutt for kulturstudier og orientalske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Mai 2016 II The city does not consist of this, but of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past… The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment mamrked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls. Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. III © Forfatter Ida Kathinka Skolseg År 2016 Tittel Arkitektur i konflikt: Hva er arkitekturens rolle i kampen om Jerusalem Forfatter Ida Kathinka Skolseg http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Sammendrag Israel forsøker å presentere Jerusalem som en forent by, hvis udelelige egenskap er basert på Jerusalems rolle som jødenes religiøse, historiske og politiske hovedstad. Den politiske dimensjonen av "å bygge landet Israel" er en fundamental, men samtidig en skjult komponent av enhver bygning som blir konstruert. Den politiske virkeligheten dette skaper er ofte mer konkluderende og dominerende enn hva den stilmessige, estetiske og sensuelle effekten av hva en bygning kan kommunisere. "Ingen er fullstendig fri fra striden om rom", skriver Edward Said, "og det handler ikke bare om soldater og våpen, men også ideer, former, bilder og forestillinger." 27. juni, to uker etter at Seksdagerskrigen endte i 1967, ble 64 kvadratkilometer land og ca. -

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile

Sur Bahir & Umm Tuba Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jerusalem Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jerusalem Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all villages in Jerusalem Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in the Jerusalem Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jerusalem Governorate. -

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

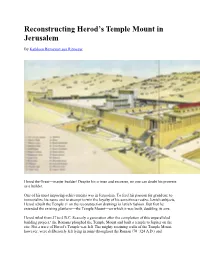

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

Jerusalem Hanukkah Vacation

Jerusalem Hanukkah vacation Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Jerusalem Hanukkah vacation Our Jerusalem Hanukkah vacaon, the best of Jerusalem in 3 days: Mahne Yehuda market, the Arab market, the David tower, Western wall, Al-Aqsa Mosque, Yad Vashem Museum and more.... Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Warning: count(): Parameter must be an array or an object that implements Countable in /var/www/dev/views/templates/pdf_day_images.php on line 4 Day 1 - Arrival to Jerusalem Accomodation: Rafael Residence Boutique Notice: Trying to get property 'address' of non-object in /var/www/dev/views/pdf.php on line 435 Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Arrival to Jerusalem 3. Mahane Yehuda Market apartment building in Hong Kong "Azura", song on the album 1. Tel Aviv-Yafo Don Solaris by 808 State MS Azura, a cruise ship in the P&O Duration ~ 2 Hours Cruises fleet Azura, a tular see in the Roman Catholic Church Duration ~ 2 Hours Mahane Yehuda Market, Jerusalem Azura, the alias of fictional character Romwell Jr in the more.. Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel Website: www.tel-aviv.gov.il WIKIPEDIA 5. Nahalat Shiv'a WIKIPEDIA Mahane Yehuda Market, oen referred to as "The Shuk", is a marketplace in Jerusalem, Israel. Popular with locals and Duration ~ 1 Hour Tel Aviv is the second most populous city in Israel—aer tourists alike, the market's more than 250 vendors sell fresh Nahalat Shiv'a, Jerusalem, Israel Jerusalem—and the most populous city in the conurbaon of fruits and vegetables; baked goods; fish, meat and cheeses; Gush Dan, Israel's largest metropolitan area. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

Nickolay Mladenov Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Security Council Briefing on the Situation in the Mi

(As Delivered) NICKOLAY MLADENOV SPECIAL COORDINATOR FOR THE MIDDLE EAST PEACE PROCESS SECURITY COUNCIL BRIEFING ON THE SITUATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF UNSCR 2334 (2016) 29 September 2020 Mister President, Members of the Security Council, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I will devote this briefing to presenting his fourteenth report on the implementation of Security Council resolution 2334, covering the period from 5 June to 20 September of this year. Before presenting the report, I would like to note the recent agreements between Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. The Secretary-General welcomes these agreements, which suspended Israeli annexation plans over parts of the occupied West Bank. The Secretary-General hopes that these developments will encourage Palestinian and Israeli leaders to re-engage in meaningful negotiations toward a two-State solution and will create opportunities for regional cooperation. He reiterates that only a two-State solution that realizes the legitimate national aspirations of Palestinians and Israelis can lead to sustainable peace between the two peoples and contribute to broader peace in the region. I am similarly encouraged by the call to restore hope in the peace process and resume negotiations on the basis of international law and agreed parameters, as made by the Foreign Ministers of Jordan, Egypt, France and Germany in Amman. The recent moves toward strengthening Palestinian unity as demonstrated by the outcome of the Fatah-Hamas meetings calling for long-awaited national presidential and legislative elections are also encouraging. Elections and legitimate democratic institutions are critical to uniting Gaza and the West Bank under a single national authority vital to upholding the prospect of a negotiated two-State solution. -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2014 Human

ISRAEL 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multi-party parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “State of Emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in January 2013, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) During the year a number of developments affected both the Israeli and Palestinian populations. From July 8 to August 26, Israel conducted a military operation designated as Operation Protective Edge, which according to Israeli officials responded to increases in the number of rockets deliberately fired from Gaza at Israeli civilian areas beginning in late June, as well as militants’ attempts to infiltrate the country through tunnels from Gaza. According to publicly available data, Hamas and other militant groups fired 4,465 rockets and mortar shells into Israel, while the government conducted 5,242 airstrikes within Gaza and a 20-day military ground operation in Gaza. According to the United Nations, the operation killed 2,205 Palestinians. The Israeli government estimated that half of those killed were civilians and half were combatants, according to an analysis of data, while the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs recorded 1,483 civilian deaths--more than two-thirds of those killed--including 521 children and 283 women; 74 persons in Israel were killed, among them 67 combatants, six Israeli civilians, and one Thai civilian.