SOME CLIMBS in KOREA. by C. H. Archer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Correspondence

234 CORRESPONDENCE CORRESPONDENCE . ' St. John's School, Leatherhead, Surrey Sep~ember 28, 1955. ·The Editor, the ALPINE JouRNAL. · SIR, I was much impressed by the somewhat unusual article which appeared in the May number of the A.J. entitled ' The Technique of Artificial Climbing.' At first glance it was not easy to decide· which way up some of the illustrations were meant to be. Now, Sir, while I have great respect for the achievements of the exponents of this technique, I would humbly suggest that the article in question is somewhat out of place in the ALPINE JOURNAL and would better grace the pages of an engineering journal. The methods of the ' Hammer ·and Nail Co.' to quote the words of our pre-war Editor, Lt.-Col. E. L. Strutt, are alien to the traditions of the Alpine Club and to British mountaineering generally. It used to be a point of honour never to sully the face of a British climb with a piton. Let me quote the instance of the Munich climb. The visiting party of Germans in the middle 'thirties found it necessary to insert one piton in that remarkably steep and exposed face. The climb was promptly repeated by a British party who took out the piton ! Mountaineering is a sport and not a form of war. A sport is governed by a set of rules which allows each side a fair chance. Why must we use ' all out ' methods in mountaineering ? Why not let the mountain win sometimes ? The occasional piton for security perhaps, for roping off, or when caught by bad weather, but 'tension' climbing no ; etriers no ! . -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge. -

<Tlerg\?Men Anb <Tlimbing

THE LETTERS OF ST. JEROME number of pilgrims thronged to see him from all parts ; for his writings had, by their charm, their learning, their wit, their satire become celebrated throughout the whole of the Roman speaking world. Legend soon became busy with this anchorite of the cave at Bethlehem. Many stories, brought by the pilgrims of the time, and amplified by the imagination of subsequent centuries, were told about this great doctor of the West. Many of the stories are obviously silly, and many of them are false ; but the very fact that such stories were circulated even before the death of Jerome himself is sufficient evidence of his fame. But in his letters, far more than in his controversial works, or even his translations, we catch a clear and true sight of the man as he was, alike in his strength and in his weakness. There are many things we cannot either admire or approve in his conduct or in his writings ; but, when all is said and done, the verdict of Professor Dill is surely the right one : " He added to the monastic life fresh lustre by his vivid intellectual force and by his contagious enthusiasm for the study of Holy Writ." <tlerg\?men anb <tlimbing. BY THE REV. w. A. FURTON, B.A. T is not easy to explain the precise nature of the fascination I that mountaineering possesses for any of its followers. The ordinary man looks upon it with a kind of amused contempt that finds expression in pitying remarks or patronizing inquiries. But to the extraordinary man who has been " bitten," it is an enthusiasm, an obsession, a paramount source of pure delight. -

Glacier National Park, 1917

~ ________________ ~'i DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / FRANKLIN K. LANE. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVI'CE,/ STEPHEN T. MATHER. DIRECTOR GENERAL ~FO ~N GL CIER NAL ONAL PARK Season of 191 7 The Alps of America-Wonderful Tumbled Region Possessing 60 Glaciers. 250 Lakes, and M y Stately Peaks-Precipices 4,000 Feet Deep-Valleys of Astonish ing Rugged B auty-Scenery Equaling Any in the World- Large, Excellent Hotels and Comfortable Chalet Camps-Good Roads- The Gunsight Trail Across the Top of the Range-Good Trout Fishing-How to Get There-What to See-What to Wear lor MOUiltain Climbing WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 TI-IE NATIO .... PARKS AT A GLANCE ( Chron010gIca,l.ly In the order of theIr creatIon [Number,14; Total Area, 7,290 Square Miles] NATIONAL AREA PARKS In DISTINCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS In order of LOCATION square creation miles H ot Springs •..... Middle H 46 hot springs possessing curative properties-Many hotels and 1832 Arkansa.s boording houses-20 bathhouses under public control. CONTENTS. Yellowstone . ••••. North- 3,348 More geysers than in al1 rest of world together-Boiling 1872 western springs-Mud volcanoes-Petrified forests-Grand Canyon Page. Wyoming of the YelIowstone, remarkable for gorgeous coloring-Large General description_ .. _. _. ........ ..... .... ... ... ...... ........ .. 5 lakes-Many large streams and waterfalls-Vast wilderness A romance in rocks . • _. __ . _. _.. .......................... _. ....... 5 inhabited by deer, elk, bison, moose, antelope, bear, moun- The Lewis overthrust .. __. .... _............................... ...... 6 tain sheep, beaver, etc., constituting greatest wild bird and A general view _ . _____ .. ..... ................................. 6 animal preserve in world-Altitude 6,000 to 11,000 feet- The west side .... -

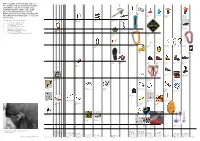

Representation in Chronological Order of the Evolution and Development of Products and Artifacts Related to Mountaineering and H

Representation in chronological order of 1800 1850 1880 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 the evolution and development of products and artifacts related to mountaineering and high mountain activities. The graph places in temporal line the technical improvements developed in correlation with RURP Longware Bong 1959 1964 the achievement of main alpine ascents and Portaledge Camel Bag Avalanche Electric 1970 1989 Backpack avalanche new records. 1997 Backpack A MOUNTAINEERS INNOVATION KEY PRODUCTS Piton Knifeblade Piton Expansion Bolt Lost Arrow 20th Century 1910 1930 1946 A Expansion Bolt, Laurent Grivel, 1930 B Kernmantel Rope, Edelrid, 1953 C Gorotex Membrane, 1976 D New Safety level of Carabiner, 1953 Inflatable Double Gate, Grivel, 2016 Portaledge E Vibram Sole, Vitale Bramani, 1935 B 2019 Static Rope Nylon rope Kernmantel F Full Webbing Harness, Whillans Sit, 1970 1949 rope 1953 G Grigri Discensorm, Petzl, 1991 1800 H Friends and temporary protection, Ray Jardine, 1973 C N-3B PARKA Gorotex 1935 1976 D Karabiner D Shape Snap Gate Quickdraw Wire Gate Screw Gate Captive Double Gate 1910 1937 1953 1970 1991 2000 2016 2016 Tranceiver Tranceiver Tranceiver 1968 1986 2018 E Vibram Carrarmato Alta Quota Danner Boots Koflach Modern Hiking Trail Running 1935 1937 1970 1979 1990 Boots Shoes 2013 Swiss Knife 1884 Mythos Speed 1991 Mountaineering 2010 F Rope Harness Chest Harness Whillans Sit Har- Modern 1800 1967 ness 1970 Harness 2000 CRAMPONS Modern Two poin Rigid crampon Automatic 16TH CENTURY Crampon 1909 Crampons -

CLIMBS with MEDICAL and WEATHER COMPLICATIONS 347 • • Jungle of Heather, Birch and Rowan, Boulders and Peat, Which I Have Never Succeeded in Circumnavigating

CLIMBS WITH MEDICAL AND WEATHER COMPLICATIONS 347 • • jungle of heather, birch and rowan, boulders and peat, which I have never succeeded in circumnavigating. With Dr. Johnson, I have always felt that ' a walk upon ploughed fields in England is a dance upon carpets compared with the toilsome drudgery of wandering in Skye.' But for all the scratche~ the ridge remains the finest mountaineering • expedition in the British Isles. Or perhaps it is on4y the best but one ; for it has ·one . sad disadvantage· for the real hero. Its completeness is . spoilt by those two awkward outposts of the Black Coolin, isolated amongst the Red Coolin, Blaven and Clach Glas. Blaven is perversely just over 3000 feet high, so that for a gatherer of Munros a traverse of the main ridge leaves one· still to pluck. In June 1939, Charleson and Forde started from a camp at the foot of Gars Bheinn, traversed the whole of the main ridge to Sgurr na h'Uamha, with snow and ice part of the way ; and after a meal and a rest at a camp in Harta Corrie, went up Clach Glas and Blaven and came back to their tent in Harta Corrie, the whole expedition taking five minutes less than 24 hours. Three months later Murray and Donaldson, setting out from Glen Brittle, sustained by vita-glucose and revived with draug4ts of navy rum and Bovril, repeated the feat with half an hour to spare. So history once more repeats itself, and the finest expedition in the British Isles, already only a preliminary tC? an ascent of Blaven and Clach G las, is fast becoming an ' Easy Day for a Lady.' . -

Winter Wandering Is Gaining Traction by Ira Orenstein

Winter Wandering is Gaining Traction by Ira Orenstein Another wonderful year of spring, summer and fall hiking has gone by, preserved in memories and in the plethora of acquired precious images to be sorted and viewed during what for some is an upcoming sedentary winter. For many outdoor enthusiasts exploring the mountains is a seasonal activity that ends needlessly with the coming of the short, snowy winter days ahead. A visit to your favorite outdoor shop will confirm however that there is no shortage of equipment and supplies available to permit the hiker to explore and enjoy wilderness trails year-round. The focus of this article is to discuss how to select proper traction to remain vertical and prevent slipping while walking or hiking on ice and snow-covered terrain. Let’s start with the simplest form of traction. One winter day my family set out to climb Hunter Mountain in New York’s Catskill Park. After pulling into the parking area I realized after taking my first step out of the car that I was atop glassy smooth ice. Snow or ice in the lot had melted the day before and re-froze overnight into water-ice, which can make for extremely slippery conditions that can be even more challenging if the ground is sloping (we can also throw in a coating of fluffy snow to obscure the underlying ice for good measure). In this instance even with the parking lot being flat I couldn’t gain enough traction to stand up, let alone walk to the trunk where our snowshoes and crampons were located. -

Festival of Climbing All Tooled up Going In

30916_Cover 6/11/01 4:22 pm Page 1 ISSUE 24 - WINTER 2001 £2.50 Festival Of Climbing Are You Ready For It ? All Tooled Up Ice Axe Development Going In The John Muir Trust ACT COMPETITION SOUTH AMERICA AVALANCHE TRANSCEIVERS BMC CHANGES • EXPEDITIONS • MOUNTAIN TRAVEL • MALLORY FOREWORD... GLOBAL SUMMITS (LEFT) The UIAA Summit Charter. (TOP) Roger Payne contemplating global summits. At first sight it may seem strange to suggest the Cuillins of Skye as a possible peace park. However, Skye has been the scene of clan battles, and the Glen Brittle Memorial Hut was erected in memory of all those who fell during the sec- ond world war. Also, following the failure of the disputed sale of the Cuillins perhaps John MacLeod of MacLeod will be prepared to renounce any ownership claim. What a fantastic gesture that would be as a commitment to peace and freedom in the International Year of Mountains. At the launch of the UIAA Summit Charter Robert Pelousek the deputy education minister for Austria was in the mood to make gestures. In an excellent speech in which he high- lighted the many benefits of climbing and mountaineering he announced that Austria would like to see indoor climbing as a component of sports education for all 6 to 11 year olds. He amusingly pointed out that anyone who can learn o, what does it mean that the United Nations to climb and walk in mountains when they are young “…will has designated 2002 as the International Year have no problem moving around on the slippery flatlands Sof Mountains? Will mountains get bigger later in life!” during the year? Or perhaps gravity will be reduced to make them easier to climb? Anyway, isn’t the There is lots happening to celebrate the International Year UN busy solving global problems? of Mountains with various launch events at the Festival of Climbing on 7 to 9 December including the launch of the The response that the mountaineering federations have Access and Conservation Trust with Alan Michael MP, the taken to the International Year of Mountains (IYM2002) is Minister for Rural Affairs. -

Swiss Letters and Alpine Poems

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com 600022057M II 600022057M I aM z z o .t » * NE. -».'-< » T» -u$'f?mT ?%* ; Jr.* ' - Swiss Letters AND ALPINE POEMS. BY THE LATE FRANCES RIDLEY HAVERGAL. EDITED BY HER SISTEK, J. MIRIAM CRANE. JAN'F«2 .) JAMES NISBET & CO., 21, BERNERS STREET. 203 butler & tanner, the selwood printing works, Frome, and London. PREFATORY NOTE. THE world-wide interest excited by the writings and " Memorials " of my lamented sister, Frances Ridley Havergal, has led her family to think that such of her letters as I have been able to collect, written to her home circle from Switzerland, will be acceptable to her many admirers. Some will feel pleasure in mentally revisiting the sublime scenery she describes with such vigour and simplicity ; and others will be inter ested in observing how unconsciously these letters illustrate her enthusiastic nature, her practical ability, and her ardent desire that every one should share her earthly pleasures and her heavenly aspirations. JANE MIRIAM CRANE. Oakhampton, near Stourport, October 20, 1881. CONTENTS. I. Encyclical Letter in 1869, during a tour with HER BROTHER-IN-LAW, HENRY CRANE, HIS WIFE, AND DAUGHTER MIRIAM LOUISA . page I-IOI Dover — Calais — Brussels — Obercassel — Bingen — Heidel berg — Baden — Basle — Neuhausen — Rhine Falls — Zurich — Berne — Thun — Interlachen — Lauterbrunnen — Miirren — Grindelwald — Giessbach — Meyringen — Rosenlaui — Briinig Pass — Lucerne — The Rigi — Altdorf — Langnau — Fribourg — Vevey — Montreux — Glion — St. Gingolph — Novelles — Chillon — Bouveret — Gorge du Trient — Martigny — T6te Noire— Col de Balm — Chamouni — Pierre a 1' Echelle — La Flegere — Montanvert — Mer de Glace— Mauvais Pas — St. -

Anna Kacperczyk University of Lodz, Poland Between Individual and Collective Actions

Anna Kacperczyk University of Lodz, Poland Between Individual and Collective Actions: The Introduction of Innovations in the Social World of Climbing DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.15.2.08 Abstract This article, which is based upon the findings of a seven-year research project concerning the social world of climbing, discusses climbing as an organized social practice that possesses a strong historical dimen- sion and collective character. It examines the relation between individual participants and that social world as a whole, and it accepts that an individual’s personal life may be inscribed in the development and formation of that world in two ways. These are 1) a given social world imposes the behavioral pat- terns, normative rules, institutional schemes of actions, and careers upon participants that characterize their identities and actions; and 2) the actions of an individual participant trigger significant change in that world. I am particularly interested in those unique situations in which when a participant induces a change that affects a given social world (or a sub-world) as a whole, and discuss two examples of this relation, namely, the history of designing and creating climbing equipment, and setting new standards of climbing performance. Briefly stated, innovative solutions are born in conjunction with particular climb- ing actions that are either promoted or hindered depending on whether or not the vision of the primary activity associated with those solutions was accepted by the majority of participants. The dynamics and transformations of the social world in question thus rely upon the activities of exceptional individuals who, as pioneers, innovators, and visionaries, attain mastery in performing the primary activity of that world and set new standards of performance for others. -

Spedizioni Escursionismo Alpinismo

CAI SET_OTT 08 10-09-2008 18:44 Pagina a1 SETTEMBRE OTTOBRE 2008 st. – 45% art. 2 comma 20/b legge 662/96 - Filiale di Milano. Alpinismo Nadelgrat, Tofana di Rosez Monte Cristallo Escursionismo Parco del Pollino, Vanoise e Gran Paradiso Spedizioni Torre del Paine Settembre Ottobre 2008 Supplemento bimestrale a la “Rivista del a la 2008 Supplemento bimestrale Ottobre Settembre Alpino Italiano - Lo Scarpone” Club Po 10/2008 - Sped. in abb. N. CAI SET_OTT 08 10-09-2008 18:44 Pagina a2 Photo © LA SPORTIVA Vi parliamo della bellezza dello scoprire, di sentire una passione, di avere addosso is a trademark of the shoe manufacturing company “La Sportiva S.p.A” located in Italy (TN) un’emozione. Di uscire, respirare, vivere. ® Ascolta il tuo Outdoor Instinct LA SPORTIVA .com ?L; DD H 7 I 7 Trango ALP Trango Trango TREK Trango < H Trango S EVO Trango < < O lasportiva www. CAI SET_OTT 08 10-09-2008 18:44 Pagina 1 Intercettare il mutamento dell’epoca: non solo un refrain ma un preciso progetto per il CAI. E pren- dendo l’occasione dell’incontro con il mondo Scout, inizia un percorso dentro e fuori l’associazione che probabilmente l’anno prossimo ci porterà verso gli “Stati Generali della Gioventù” in montagna e per la montagna. Al centro sono approcci nuovi e valori di sempre che affascinano lo spirito gio- vanile, l’ambiente da conoscere e difendere, l’empatia con la natura, la scoperta culturale, il gusto della socialità e il mutuo aiuto. Non da ultimo, il recupero della fatica sul sentiero o in parete, come Photo © LA SPORTIVA simbolo di “riscoperta di una vita autentica” di Pier Giorgio Il tema è: riusciamo a parlare e ad agire rispetto al mondo giovanile senza sfiorare Oliveti nel lessico, nel timbro, nell’esempio, l’agguato della “retorica”, tanto poco sopportabile agli orecchi e agli occhi delle nuove generazioni ? Proviamoci, almeno. -

Été 2019 La Montagne En Partage

ASCENSIONS printemps été 2019 La montagne en partage club alpin Strasbourg ASCENSIONS printemps été 2019 1919-2019 Votre club a 100 ans ! SOMMAIRE EDITO 3 ACTIVITÉS 5-29 Alpinisme 6-9 Escalade 10-17 Slackline 18 Ski Alpinisme 19-21 Randonnée Pédestre 22-25 Canyon - Spéléo 26-29 Vie du Club 30 Couverture : Lucas Schwinte dans la face Nord de l’Ober Gabelhorn (photo F. Willmann) Prochain bulletin : novembre 2019 Vos contributions, textes (word) et photos (jpeg), sont à adresser à Jean-Marc Chabrier ([email protected]) avant le 30 septembre 2019 LE CLUB ALPIN DE STRASBOURG 6, boulevard du Président Poincaré 67000 Strasbourg Secrétariat : Marta vous accueille du mardi au vendredi de 17h à 19h Téléphone : 03 88 32 49 13 Courriel : [email protected] Site internet : http://clubalpinstrasbourg.org (contact : [email protected]) Directeur de la publication : Jean-Marc Chabrier Rédacteur en chef : Jean-Marc Chabrier Mise en page : Fabrice Cognot Imprimé par JUNG à Geispolsheim - Dépôt légal : avril 2019 EDITO Adapter nos pratiques Alors que nous fêtons les 100 ans de notre Club Alpin, il n’est pas inutile de nous pencher sur nos pratiques. Le contexte a bien changé depuis 1919, et nous devons aujourd’hui faire face à de nombreuses évolutions. J’aimerais m’attarder sur deux d’entre elles : le réchauffement climatique, qui impacte directement nos espaces naturels, et la surfréquentation de certains de ces espaces. Le réchauffement climatique est une réalité ; sa cause en partie humaine aussi. Il nous appartient d’y remédier au mieux, et cela passe entre autres par une baisse de notre bilan carbone lors de nos sorties CAF.