Willi Soukop Interviewed by Andrew Lambirth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9789004250994.Pdf

Fragmenting Modernisms China Studies Edited by Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 24 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/CHS Fragmenting Modernisms Chinese Wartime Literature, Art, and Film, 1937–49 By Carolyn FitzGerald LEIDEn • bOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Ye Qianyu, “Stage Set,” from the 1940 sketch-cartoon series Wartime Chongqing. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data FitzGerald, Carolyn. Fragmenting modernisms : Chinese wartime literature, art, and film, 1937-49 / by Carolyn FitzGerald. pages cm. — (China studies ; v. 24) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) 1. Chinese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Literature and the war. 3. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Art and the war. 4. China—History—Civil War, 1945–1949—Literature and the war. 5. China—History— Civil War, 1945–1949—Art and the war. 6. Motion pictures—China—History—20th century. 7. Art, Chinese—20th century. 8. Modernism (Literature)—China. 9. Modernism (Art)— China. I. Title. PL2302.F58 2013 895.1’09005—dc23 2013003681 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. -

HKUST Institutional Repository

The Dance of Revolution: Yangge in Beijing in the Early 1950s* Chang-tai Hung ABSTRACT Yangge is a popular rural dance in north China. In the Yan’an era (1936–47) the Chinese Communist Party used the art form as a political tool to influence people’s thinking and to disseminate socialist images. During the early years of the People’s Republic of China, the Communists introduced a simpler form of yangge in the cities. In three major yangge musicals performed in Beijing, the Party attempted to construct “a narrative history through rhythmic movements” in an effort to weave the developments of the Party’s history into a coherent success story, affirming various themes: the support of the people, the valour of the Red Army, the wise leadership of the Party and the country’s bright future. However, urban yangge’s simplicity as an art form, the professionalization of art troupes, the nation’s increas- ing exposure to a variety of alternative dance forms and, worse still, stifling government control all contributed to the rapid decline of this art form in urban China. Unlike the Bolsheviks, who at the time of the October Revolution of 1917 had little experience with political art forms, the Chinese Communists, before their seizure of power in 1949, had skilfully employed the popular art media to conduct an effective propaganda campaign among the mostly illiterate peasant inhabitants of rural China. The story of their use of such rural art forms as storytelling and yangge dance as a political tool during the Yan’an era (1936–47) is now relatively well known.1 Yet their use in the post-Yan’an period, particularly after the establishment of the Peo- ple’s Republic of China (PRC) in1949, has rarely been examined. -

From Trinidad to Beijing Dai Ailian and the Beginnings of Chinese Dance

1 From Trinidad to Beijing Dai Ailian and the Beginnings of Chinese Dance Dong d-dong, dong d-dong. A gong sounds as the camera fixes on an empty stage set with an arched footbridge and blossoming tree branch. Dai Ailian emerges dressed in a folkloric costume of red balloon pants and a rose-colored silk jacket, a ring of red flowers in her hair and shoes topped with red pom-poms. Puppetlike, two false legs kick out from under the back of Dai’s jacket, while the false torso and head of an old man hunch forward in front of her chest, creating the illusion of two characters: an old man carrying his young wife on his back. This dance is Dai’s adaptation of “The Mute Carries the Cripple” (Yazi bei feng), a comic sketch performed in several regional variations of xiqu, or Chinese traditional theater (video 1). This particular version is derived from Gui opera(Guiju), a type of xiqu specific to Guangxi Autonomous Region in south China. Dai demonstrates her dance skill by isolating her upper body and lower body, so that her pelvis and legs convincingly portray the movements of an old man while her torso, arms, and head those of a young woman. As the man, Dai takes wide sweeping steps, kicking, squatting, and balancing with her feet flexed and knees bent between steps, occa- sionally lurching forward as if struggling to balance under the weight of the female rider. As the woman, Dai grips the old husband’s shoulders with one hand while she lets her head bob from side to side, her eyes sparkling as she uses her free hand to twirl a fan, point to things in her environment, and dab the old man’s forehead with a handkerchief. -

When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950S and 1960S

China Perspectives 2020-1 | 2020 Sights and Sounds of the Cold War in Socialist China and Beyond When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s Emily Wilcox Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/9947 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.9947 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2020 Number of pages: 33-42 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Emily Wilcox, “When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s”, China Perspectives [Online], 2020-1 | 2020, Online since 01 March 2021, connection on 02 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ chinaperspectives/9947 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.9947 © All rights reserved Special feature china perspectives When Folk Dance Was Radical: Cold War Yangge, World Youth Festivals, and Overseas Chinese Leftist Culture in the 1950s and 1960s EMILY WILCOX ABSTRACT: This article challenges three common assumptions about Chinese socialist-era dance culture: first, that Mao-era dance rarely circulated internationally and was disconnected from international dance trends; second, that the yangge movement lost momentum in the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC); and, third, that the political significance of socialist dance lies in content rather than form. This essay looks at the transformation of wartime yangge into PRC folk dance during the 1950s and 1960s and traces the international circulation of these new dance styles in two contexts: the World Festivals of Youth and Students in Eastern Europe, and the schools, unions, and clan associations of overseas Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, and San Francisco. -

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People's Republic of China

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Xin Liu, Chair Professor Vincanne Adams Professor Alexei Yurchak Professor Michael Nylan Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2011 Abstract The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Xin Liu, Chair Under state socialism in the People’s Republic of China, dancers’ bodies became important sites for the ongoing negotiation of two paradoxes at the heart of the socialist project, both in China and globally. The first is the valorization of physical labor as a path to positive social reform and personal enlightenment. The second is a dialectical approach to epistemology, in which world-knowing is connected to world-making. In both cases, dancers in China found themselves, their bodies, and their work at the center of conflicting ideals, often in which the state upheld, through its policies and standards, what seemed to be conflicting points of view and directions of action. Since they occupy the unusual position of being cultural workers who labor with their bodies, dancers were successively the heroes and the victims in an ever unresolved national debate over the value of mental versus physical labor. -

DAF Media Release Neal and Massy Foundation

MEDIA RELEASE NEAL & MASSY FOUNDATION SUPPORTS THE DAI AILIAN FOUNDATION The Neal & Massy Foundation is the first local organisation to support the Dai Ailian Foundation. The Dai Ailian Foundation was formed last year to honour and 7 St. Ann’s Road promote the life and work of Dai Ailian who was born in Trinidad in 1916 and is St. Ann’s Trinidad, W.I. internationally acclaimed and highly revered in the People’s Republic of China. (868) 624-7150 The International Theatre Institute, Paris, France, will honour Madam Dai in their th 30 Anniversary publication for International Dance Day at UNESCO this year. One of the Dai Ailian Foundation’s objectives is to offer performing arts scholarships and two young dancers, Juan Pablo Alba Dennis from Port of Spain, and Seon Nurse from Laventille, were awarded 1-year dance scholarships at the prestigious Beijing Dance Academy in Beijing, the People’s Republic of China, commencing last September and finishing July 2012. The Dai Ailian Foundation is proud of these two young men – the Beijing Dance Academy is impressed with their talent and application to work and Juan Pablo and Seon are enjoying their learning and cultural experiences while at the same time being great Trinidad and Tobago ambassadors. The Neal & Massy Foundation, formed in 1979, is a very successful Non- Government Organisation that practices good corporate social responsibility by their support of numerous projects and annual grants to charitable organisations such as the Dai Ailian Foundation. The Dai Ailian Foundations sincerely thanks the Neal & Massy Foundation for their support on behalf of the two scholarship winners. -

Magisterarbeit

MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit „Kontextualisierte Betrachtung des Modellstücks Das rote Frauenbataillon als sinisiertes Hybridprodukt vor dem Hintergund der chinesischen Modernisierungsanstrengungen― Verfasserin Bakk. phil. Ulrike Kniesner angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 811 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Sinologie Betreuerin: Univ.- Prof. Dr. Susanne Weigelin-Schwiedrzik Meiner Schwester i Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 EINLEITUNG .......................................................................................................... 1 2 EXKURS: TANZ IN CHINA ................................................................................... 18 2.1 HISTORISCHER RÜCKBLICK ................................................................................................ 22 2.2 WESTLICHER IMPORT DES EURPÄISCHEN BÜHNENTANZES NACH CHINA: DIE CHINESISCHE TANZSZENE IN DER ERSTEN HÄLFTE DES 20. JAHRHUNDERTS ................................................. 25 2.2.1 Wu Xiaobang und Dai Ailian – Pioniere des Zeitgenössischen Tanzes in China ................ 29 2.3 TANZ IN CHINA UNTER MAO ZEDONG ............................................................................... 30 2.3.1 Kulturrevolutionäre Modelle an vorderster Front: Die Jahre 1966-1976 .............................. 35 2.4 TENDENZEN IM TANZ IN CHINA HEUTE: VON DEN 80ERN INS 21. JAHRHUNDERT ................ 39 3 TANZ UND POLITIK ............................................................................................ -

"Folk Dance in China: the Dance Pioneer Dai Ailian 1916-2006"

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Baruch College 206 "Folk Dance in China: the Dance Pioneer Dai Ailian 1916-2006" Eva S. Chou CUNY Bernard M Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_pubs/1203 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Folk Dance in China: The Dance Pioneer Dai Ailian, 1916–2006 Eva Shan Chou became interested in this topic through my work in the history of ballet in China, in which Dai Ailian was a vital figure, especially in the ballet’s early years. Her role, I undoubtedly major and yet enigmatic to a historian, drew my attention to how, a decade earlier, she had been an equally vital figure in the early years of folk dance in China, when knowledge of such dances first began to reach outside their indigenous com- munities. I perceived many parallels both in her energetic deployment of her talents and in the later portrayals of her role, and found that the existence of two rather than one such phenomena helped one to clarify the other. This paper focuses only on the earlier case, her pioneering role in folk dance. I hope you will come away from my presentation with two points: (1) a clearer picture of one early and concrete instance of what we could call dance ethnography, and (2) by con- trast, a quick view of folk dance on the large scale in which it exists today, supported by its largest funder, the government. -

Emily E. Wilcox(魏美玲)

Emily E. Wilcox(魏美玲) Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese Studies, Department of Asian Languages Cultures University of Michigan [email protected] / (001) 415-846-2234 EDUCATION Ph.D. Anthropology Department, University of California, Berkeley, 2011 Dissertation: The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 Program: Medical Anthropology (joint with the University of California, San Francisco) Committee: Xin Liu, Vincanne Adams, Shannon Jackson, Michael Nylan, Alexei Yurchak Visiting Graduate Student. Beijing Dance Academy, Beijing, 2008-2009 Program: Masters program in Chinese dance technique, history, and theory Language Training. Inter-University Program, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 2007-2008 Program: Advanced Modern and Classical Chinese Language Training. Princeton in Beijing Program, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 2005, 2006 Program: Advanced and Intermediate Chinese M.Phil. Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, 2004 A.B. magna cum laude. Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, 2003 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor of Modern Chinese Studies. Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, 2013-present Courses taught: Contemporary Chinese Performance Culture, Freshman Seminar “China in Ten Words,” Great Cities of Asia (China), Junior/Senior Seminar Program Director. Reves Center for International Education at the College of William and Mary, Summer Study Abroad Program in Beijing, June-August 2013 -

Searchable PDF Format

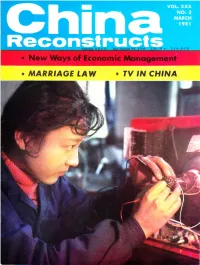

c t8 &.!,s {: ...{ Give the People Some Sweetness (woodcut, 1979) t\g PUBLTSHED MONTHLy GERMAN, cHlNEsE BY THE cHINA.tN-.ENgll_S.t-+-IEEryCfl, wrlrAne rnsfrrure 5_t4l,ilSE.ARABIC, tsoolc -txriiio'-[r'nG,'-afnr-Rttiiii.r] PORTUGUEsE AND vot. xxx No. 3 MARCH 1981 Articles of the Month CONTENTS Economy Reforming Economic Monogement Beforming Economic Managemenl 4 Chino's economy, Vast Changes in Naniing port 24 omidst reolistit od- justment torgets A Day in a Mountain Village 54 ol . ond priorities, is olso Questions of Moruioge the scene of initiol re- Why New Marriage Law Was Necessary lorms in its monoge- 17 ment Why they ore Finding a Wife,i Husband in ghanghai 21 needed, benelits re- Questions ond Answers reoled, new contro- dictions enGountered ls China 'Going Backward'? 8 - discus3ed by on Medio economist Poge ,l Entering the Television Age 11 China's Voice Abroad 52 Everyone Equo! Before the Low Low I Deportment of Beijirng Univer' Everyone Equal Before Membe the Law 28 sity ons the procedure, principles, legol Culture issues i of Jiong Qing ond other cul' prits conce for the luture. Pqge 28 Determined Philatelist Shen Zenghua 3l - Gu Yuan's Woodcuts and Watercolors JJ Yangzhou Papercuts and Zhang yongshou 46 Chino Enters Television Dai Ailian Fifty Years a Dancer 49 - Age Songfest in Guangxi 61 Qrowing production of TV Sports sets, now owned by millions. 'Monkey'Boxing 42 Moin content ol progroms Across the Lond news, entertoinment, -issue-oiring, educotioiiol Go Fly a Kite 27 courses - ond odvertising. Purple Sand Teaware of Yixing 40 Poge lt . -

La Danse Selon Ye Qianyu, Peintre Du Vingtième Siècle : De L’Inde À La Chine Marie Laureillard

La danse selon Ye Qianyu, peintre du vingtième siècle : de l’Inde à la Chine Marie Laureillard To cite this version: Marie Laureillard. La danse selon Ye Qianyu, peintre du vingtième siècle : de l’Inde à la Chine. Véronique Alexandre Journeau et Christine Vial Kayser. Penser l’art du geste : en résonance entre les arts et les cultures, L’Harmattan, pp.95-110, 2017, L’Univers esthétique, 978-2-343-12714-9. hal- 01599144 HAL Id: hal-01599144 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01599144 Submitted on 7 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LA DANSE SELON YE QIANYU, PEINTRE DU XXe SIÈCLE : DE L’INDE À LA CHINE Marie LAUREILLARD La représentation du mouvement a toujours constitué un défi pour les artistes. Elle est une sorte d’oxymore, puisque la peinture, par nature statique, se fixe ici pour objectif la saisie du mouvement ou du geste. Le peintre chinois Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-1995), connu dans les années 1930 pour ses caricatures et ses bandes dessinées, a été séduit à partir des années 1940 par la danse, dynamique dans son essence et qui apparaît le seul art naturel, avec le chant, comme le souligne André Leroi-Gourhan, car ne séparant pas le corps, le geste, l’outil, la matière et le produit1. -

A Revolt from Within Contextualizing Revolutionary Ballet

4 A Revolt from Within Contextualizing Revolutionary Ballet One day in the summer of 1966, Shu Qiao, the dancer who played the heroine Zhou Xiuying in Dagger Society, was on her way to work. In her memoir, she recalls feeling that something was amiss as she walked along the streets of Shanghai.1 People in haphazard military uniforms patrolled the sidewalks, and women and shop owners were harassed in public. A sickness in Shu’s stomach manifested her impending dread. When she arrived at the ensemble, her fears were confirmed: I entered the Theater and saw large-character posters everywhere, on the walls, in the hallways, on the doors. In the rehearsal studio there were rows of large character posters strung up on wires like laundry hung in an alleyway. Suddenly, I saw my own name. It had bright red circles around it and a bright red cross through the middle. It reminded me of the ‘execution upon sentencing’ in ancient times, and a chill went up my spine. After looking down the rows, I counted at least forty or fifty names with red circles and crosses over them.2 The “large character posters” (dazi bao) that Shu describes—handwritten signs in large script hung in public places—had been developed in socialist China as a tool for average citizens to participate in political discourse. Although they had been used widely as a medium for personal attacks since at least the late 1950s, their appearance proliferated dramatically in the summer of 1966 with the launch of a new campaign known as the Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution (Wenhua da geming, hereafter Cultural Revolution).