A Revolt from Within Contextualizing Revolutionary Ballet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

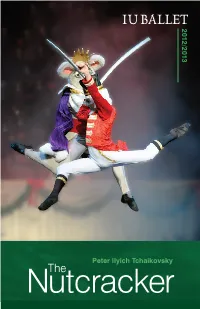

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

9789004250994.Pdf

Fragmenting Modernisms China Studies Edited by Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 24 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/CHS Fragmenting Modernisms Chinese Wartime Literature, Art, and Film, 1937–49 By Carolyn FitzGerald LEIDEn • bOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Ye Qianyu, “Stage Set,” from the 1940 sketch-cartoon series Wartime Chongqing. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data FitzGerald, Carolyn. Fragmenting modernisms : Chinese wartime literature, art, and film, 1937-49 / by Carolyn FitzGerald. pages cm. — (China studies ; v. 24) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) 1. Chinese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Literature and the war. 3. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Art and the war. 4. China—History—Civil War, 1945–1949—Literature and the war. 5. China—History— Civil War, 1945–1949—Art and the war. 6. Motion pictures—China—History—20th century. 7. Art, Chinese—20th century. 8. Modernism (Literature)—China. 9. Modernism (Art)— China. I. Title. PL2302.F58 2013 895.1’09005—dc23 2013003681 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. -

Made in BC Dance on Tour

MADE IN BC - DANCE ON TOUR January 29, 2019 ARTIST INFO RAVEN SPIRIT DANCE EARTHSONG Starr Muranko (Artistic Associate), Heather Lamoureux (Outreach Coordinator) PROJECT DESCRIPTION Earth Song – a mixed program of contemporary Indigenous dance featuring choreography by Starr Muranko & Michelle Olson, two visionary choreographers bring their diverse voices to the act of connection. Moving from Spirit to form through currents of spatial tension, these are the songs of the land and body, deeply rooted and ever reaching. Starr Muranko’s Spine of the Mother and Michelle Olson’s Northern Journey traverse territories of impulse, memory, and landscape. Additionally, the program includes the solo, Frost Exploding Trees Moon, choreographed by Michelle Olson and Floyd Favel; this piece follows the breath, instinct & impulse of a woman on her northern trap line. ARTIST PROFILE The artistic vision of Raven Spirit Dance Society is to share stories from an Indigenous worldview. Our medium is contemporary dance; and, we incorporate other expressions such as traditional dance, theatre, puppetry and multi-media to tell these stories. By sharing this work on local, national and international stages, Raven Spirit Dance reaffirms the vital importance of dance to the expression of human experience and to cultural reclamation. Raven Spirit Dance aims to explore how professional artistic work is responsive and responsible to the community it is a part of and to continue to redefine dance’s place in diverse community settings. Raven Spirit is Vancouver-based yet indelibly tied to the Yukon through its projects and inspirations, as our Artistic Director, Michelle Olson is from the Tr’ondek Hwech’in First Nation. -

Why Stockton Folk Dance Camp Still Produces a Syllabus

Syllabus of Dance Descriptions STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2018 FINAL In Memoriam Rickey Holden – 1926-2017 Rickey was a square and folk dance teacher, researcher, caller, record producer, and author. Rickey was largely responsible for spreading recreational international folk dancing throughout Europe and Asia. Rickey learned ballroom dance in Austin Texas in 1935 and 1936. He started square and contra dancing in Vermont in 1939. He taught international folk dance all over Europe and Asia, eventually making his home base in Brussels. He worked with Folkraft Records in the early years. He taught at Stockton Folk Dance Camp in the 1940s and 50s, plus an additional appearance in 1992. In addition to dozens of books about square dancing, he also authored books on Israeli, Turkish, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Greek, and Macedonian dance. STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2018 FINAL Preface Many of the dance descriptions in the syllabus have been or are being copyrighted. They should not be reproduced in any form without permission. Specific permission of the instructors involved must be secured. Camp is satisfied if a suitable by-line such as “Learned at Folk Dance Camp, University of the Pacific” is included. Loui Tucker served as editor of this syllabus, with valuable assistance from Karen Bennett and Joyce Lissant Uggla. We are indebted to members of the Dance Research Committee of the Folk Dance Federation of California (North and South) for assistance in preparing the Final Syllabus. Cover art copyright © 2018 Susan Gregory. (Thanks, Susan.) Please -

2013| 2014 Community Programs Atlanta Ballet's

2013| 2014 COMMUNITY PROGRAMS ATLANTA BALLET’S NUTCRACKER STUDY GUIDE PRESENTED BY DEAR EDUCATOR Atlanta Ballet and Atlanta Ballet Centre for Dance Education are committed to bringing you and your students the highest quality educational programs available. We continually strive to meet the ever-growing needs of students and the educational community. Please take a moment, after viewing the ballet and using the study guide, to complete the survey enclosed at the end of this guide. Your feedback is the only way we can continue to deliver high quality programs. This study guide was designed to acquaint both you and your students with Atlanta Ballet’s Nutcracker, as well as provide an interdisciplinary approach to teaching your existing curriculum and skills. This study guide was prepared by Atlanta Ballet staff members with educational backgrounds. Every attempt was made to ensure that this study guide can be used to enhance your existing curriculum. We hope both you and your students enjoy the educational experience of Atlanta Ballet and have fun along the way! Sharon Story Nicole Kedaroe Dean, Centre for Dance Education Community Division Manager TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Information and Teacher Resources Suggested Resources 4 Curriculum Connections 5 Synopsis of the Ballet 6 The Composer 7 The Choreographer 8 Choreographer History 9 History of the Nutcracker 10 History of Atlanta Ballet 11-12 History of Ballet 13 History of the Fox 14 Who’s Who in the Ballet 15 Nutcracker Vocabulary 16 Student Activities Creating a Ballet 17 Pantomime 18* Answer This 19 Who am I? 20 Extra, Extra 21 Character Education 22-23 Nutcracker Matching Quiz 24 Word Search 25 Drawing Activities 26 *This page is from the Ballet Workbook Series The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, E.T.A. -

A Dance “Festival Within a Festival” at the Fringe

A dance “festival within a festival” at The Fringe www.bookingdance.com SEE 7 DYNAMIC DANCE COMPANIES FROM AMERICA IN ONE SHOW WED, AUG 12 - SUN, AUG 16 Cover and inside cover photo:Lois Greenfield WORLD PREMIERES ABOUT BOOKING DANCE FESTIVALS ALL COMPANIES DEBUTING IN EDINBURGH FOR THE FIRST TIME The Booking DANCE FESTIVAL is the brainchild of Producer Jodi Kaplan, born with the intention of creating a cultural exchange between performing artists and international communities. The Festival occurs Welcome! annually at different locations around the globe, continually bridging dance artists and audiences worldwide. It is the long-term vision of Booking DANCE FESTIVAL to return annually to the Edinburgh Fringe for a full Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Edinburgh 2009 is the first dance “festival within a festival” three week run while additionally producing showcases in a third-world country every two years and the presented by Producer Jodi Kaplan / BookingDance at the Edinburgh Fringe. summer Olympics every four years. Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Edinburgh 2009 is a continuation of a cultural exchange between performing You will see seven of the best USA Dance Companies performing at The Fringe for the first time. artists and communities on a global scale. Last summer, coinciding with the Beijing Olympics, Jodi Kaplan Ranging stylistically from classical modern to traditional dance from around the globe, this & Associates produced Booking DANCE FESTIVAL Beijing 2008 as the first of its international productions. diverse program showcases seven innovative -

Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: an Autoethnography

The Qualitative Report Volume 25 Number 1 Article 7 1-13-2020 Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography Nan Zhang Monash University, Australia, [email protected] Maria Gindidis Monash University, Australia Jane Southcott Monash University, Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended APA Citation Zhang, N., Gindidis, M., & Southcott, J. (2020). Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography. The Qualitative Report, 25(1), 88-104. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4022 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dancing My Way Through Life; Embodying Cultural Diversity Across Time and Space: An Autoethnography Abstract In this paper, I research how my background, in different times and within diverse spaces, has led me to exploring and working with specific Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) programs. I am forever motivated to engage students learning second languages by providing them with possibilities to find out who they are, to know other ways of being and meet diverse peoples, to maintain languages more effectively and maintain culture(s) more authentically. I employ autoethnography as a method to discover and uncover my personal and interpersonal experiences through the lens of my dance related journeys. -

HKUST Institutional Repository

The Dance of Revolution: Yangge in Beijing in the Early 1950s* Chang-tai Hung ABSTRACT Yangge is a popular rural dance in north China. In the Yan’an era (1936–47) the Chinese Communist Party used the art form as a political tool to influence people’s thinking and to disseminate socialist images. During the early years of the People’s Republic of China, the Communists introduced a simpler form of yangge in the cities. In three major yangge musicals performed in Beijing, the Party attempted to construct “a narrative history through rhythmic movements” in an effort to weave the developments of the Party’s history into a coherent success story, affirming various themes: the support of the people, the valour of the Red Army, the wise leadership of the Party and the country’s bright future. However, urban yangge’s simplicity as an art form, the professionalization of art troupes, the nation’s increas- ing exposure to a variety of alternative dance forms and, worse still, stifling government control all contributed to the rapid decline of this art form in urban China. Unlike the Bolsheviks, who at the time of the October Revolution of 1917 had little experience with political art forms, the Chinese Communists, before their seizure of power in 1949, had skilfully employed the popular art media to conduct an effective propaganda campaign among the mostly illiterate peasant inhabitants of rural China. The story of their use of such rural art forms as storytelling and yangge dance as a political tool during the Yan’an era (1936–47) is now relatively well known.1 Yet their use in the post-Yan’an period, particularly after the establishment of the Peo- ple’s Republic of China (PRC) in1949, has rarely been examined. -

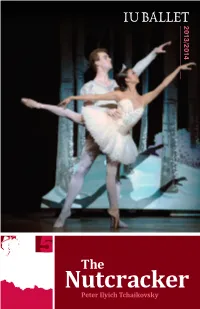

Nutcracker 5 Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season ______

2013/2014 5 The Nutcracker Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater as its 55th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffman Michael Vernon, Choreography Philip Ellis, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Design Patrick Mero, Lighting Design The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. ____________ Musical Arts Center Thursday vening,E December Fifth, Seven O’Clock Friday Evening, December Sixth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December Seventh, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December Seventh, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Eighth, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress & Children’s Ballet Mistress The children performing in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music Pre-College Ballet Program. MENAHEM PRESSLER th 90BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION Friday, Dec. 13 8pm | Musical Arts Center | $10 Students $20 Regular The Jacobs School of Music will celebrate the 90th birthday of Distinguished Professor Menahem Pressler with a concert that includes performances by violinist Daniel Hope, cellist David Finckel, pianist Wu Han, the Emerson String Quartet, and the master himself! Chat online with the legendary pianist! Thursday, Dec. 12 | 8pm music.indiana.edu/celebrate-pressler For concert tickets, visit the Musical Arts Center Box Office: (812) 855-7433, or go online to music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. -

Fit to Dance Survey: Elements of Lifestyle and Injury Incidence in Chinese Dancers

Fit to Dance Survey: elements of lifestyle and injury incidence in Chinese dancers Yanan Dang, MSc1,2; Yiannis Koutedakis, PhD1,3; Matthew Wyon, PhD1,4 1 Institute of Human Sciences, University of Wolverhampton, UK 2 Beijing Dance Academy, Beijing, China 3 Department of Sport Science, University of Thessaly, Greece 4 National Institute of Dance Medicine and Science, Walsall, UK Corresponding author Prof Matthew Wyon Institute of Human Sciences, University of Wolverhampton, Gorway Rd, Walsall, WS1 3BD, UK email: [email protected] Abstract The Fit to Dance survey has been conducted a number of times using primarily Western participants and has provided foundation data for other studies. The purpose of the current study was to replicate the Fit to Dance 2 survey focusing on features of health and injuries in pre-professional and professional Chinese dancers of different genres. Results revealed that respondents (n=1040) were from Chinese Folk dance (44.4%), Chinese Classical Dance (25.6%), ballet (10.2%) and contemporary dance (9.8%). Compared to the Fit to Dance 2 survey, alcohol consumption (29% vs 82%; p<0.01) and smoking (13% vs 21%; p<0.05) were significantly less in Chinese dancers, but a higher percentage reported using weight reducing eating plans (57% vs 23%; p<0.01) or having psychological issues with food (27% vs 24%; p<0.05). Reported injuries in a 12-month period prior to data collection were significantly lower in the current survey (49% vs 80%; p<0.01). The type of injury (muscle and joint/ligament) and perceived cause of injury (fatigue, overwork and reoccurrence of an old injury) were the same in both the current and previous survey. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Defining Self: Performing Chinese Identity Through Dance in Belfast

eSharp Issue 24: Belonging and Inclusion Defining Self: Performing Chinese Identity through Dance in Belfast Wanting Wu (Queen's University Belfast) Abstract This paper takes an auto-ethnographic approach to questions of belonging and inclusion through anthropological analysis of my own experience as a Chinese dancer in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The Chinese community in Belfast has been well established since the 1970s, retaining a distinctive identity within a city dominated by ‘British’ and ‘Irish’ ethnici- ties. Dance plays a significant role in communal ceremonies and festivals as a symbol and enactment of Chinese identity. As a Beijing trained Chinese dancer who came to Belfast as a postgraduate student, I found myself playing a significant role in the expression of Chinese identity within the city, and having emotional experiences when dancing which were differ- ent to those I had experienced in China. These experiences led me to reflect upon the sources of my own identity as a Chinese person. Through a detailed auto-ethnographic account of my dance experience as a Beijing trained dancer performing in the context of a multi-cultural city far removed from China, I explore the ways that dance may form and transform embodied identities and redefine prac- tices and selves in interaction with different environments and audiences. The article will uti- lise theorisations of “flow,” “authenticity” and “habitus” to understand the emergence of identity in embodied action. The article concludes that the perceived ‘Chineseness’ of my dance performance, and my own experience of myself as a ‘Chinese’ dancer, are rooted in ways of being that have been embodied through extensive socialisation and training from an early age.