Agrarian Conflicts Plantations in North Sumatera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(KLA) DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT SKRIPSI Oleh JUARI 150906008

POLITIK PEMBANGUNAN KABUPATEN LAYAK ANAK (KLA) DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT SKRIPSI Oleh JUARI 150906008 DEPARTEMEN ILMU POLITIK FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 Universitas Sumatera Utara UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK DEPARTEMEN ILMU POLITIK JUARI (150906008) POLITIK PEMBANGUNAN KABUPATEN LAYAK ANAK (KLA) DI KABUPATEN LANGKAT Rincian isi skripsi: 150 Halaman, 2 tabel, 13 Buku, 2 jurnal, 4 berita online, 5 situs resmi, Regulasi: 5 (Kisaran buku dari tahun 1987-2016). ABSTRAK Pembangunan yang dilakukan suatu negara tidak terlepas dari pengaruh politik. Hal ini disebabkan politik sangat menentukan proses dari pembangunan yang betujuan untuk tercapainya kehidupan suatu negara yang lebih baik. Oleh sebab itu, terciptanya suatu porgram pembangunan di suatu negara yang pada akhirnya muncul suatu kebijakan bertujuan untuk menyelesaikan suatu masalah yang dihadapi di negara tersebut. Kabupaten/Kota Layak Anak (KLA) adalah: Sistem pembangunan Kabupaten/Kota yang mengintegrasikan komitmen dan sumberdaya pemerintah, masyarakat dan dunia usaha yang terencana secara menyeluruh dan berkelanjutan dalam kebijakan, program, dan kegiatan untuk pemenuhan hak-hak anak. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui bagaimana Politik Pembangunan Kabupaten Layak Anak di Kabupaten Langkat. Metode yang digunakan pada penelitian ini adalah metode deskriptif dengan pendekatan kualitatif. Teknik pengumpulan data dengan pengumpulan data primer berupa wawancara dan observasi dilapangan, dan pengumpulan -

The Effect of Allocation of Dividend of the Regional Government-Owned

European Research Studies Journal Volume XX, Issue 4B, 2017 pp. 244-259 The Effect of Allocation of Dividend of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises and the Empowerment Efforts on the Revenue of Regional Government: The Case of Indonesia Iskandar Muda1 Abstract: The purpose of this study is to find out the factors influencing the increase in the dividend of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises (BUMD) in North Sumatera Province. In addition, it is also to determine the steps and efforts in empowering and improving the capacity of BUMD in increasing the allocation of dividend to the Regional Government of North Sumatera. It is an explanatory survey study, a study which justifies the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and explains the relationship. This study used survey for its research design. The data used in this study are primary and secondary data. The population of this study is the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises of North Sumatera Province. The samples were taken by using purposive sampling method with the stakeholders of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises of North Sumatera Province being PT. Bank Sumut, PT. Kawasan Industri Medan, PT Perkebunan Sumut, PT. Askrida and PT. Dirga Surya as the respondents, 66 in total. The method used in this study is the Descriptive Quantitative method with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) by using AMOS as the analytical tool. For the analysis of perception, this study used SPSS for the statistics. This study concluded that (1) The factors of Equity Capital (Penyertaan Modal) and Other Legitimate Local/Regional Government Revenue of Provinces and Districts/Cities can increase the sources of Local/Regional Government Revenue. -

Spatial Model of Above Ground Carbon Distribution of Mangrove in Wildlife Reserve of Karang Gading Dan Langkat Timur Laut Using Landsat 8 Satellite Imagery

Spatial Model of above Ground Carbon Distribution of Mangrove in Wildlife Reserve of Karang Gading dan Langkat Timur Laut using Landsat 8 Satellite Imagery Nurdin Sulistiyono12*, Selpandri G. Sitompul1, Desi Natalie Sinaga1, Pindi Patana1 1Faculty of Forestry, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Jl. Tridharma Ujung No.1 Kampus USU, Medan, Indonesia 2Center of Excellence for Natural Resources-Based Technology, Mangrove and Bio-Resources Group Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia Keywords: Mangrove Forests, Carbon Stock, NDVI, Landsat 8 Abstract: Wildlife reserve of KarangGading dan Langkat Timur Laut (KGLTL) in North Sumatra Province is conservation forest area where mangrove forest is the dominant type of land cover. Mangrove forest is important ecosystem because mangrove have rich-carbon stock, most carbon-rich forest among ecosystems of tropical forest. This research was based on the lack of information on the carbon stock distribution in Wildlife reserve of KGLTL. The objective of this study was to formulate the mangrove above ground carbon stock estimation model using landsat 8 satellite imagery, as well as to develop a carbon stock distribution map based on the selected model. The study found that the normalize different vegetation index(NDVI) has a considerably high correlation with the above ground carbon is 0.8280. On the basis of the values of aggregation deviation, mean deviation, bias, root mean square error, paired sample t test, and R², the best model for estimating the mangrove above ground carbon is -172.00 + 552.89 NDVI with the R² value of 68.48%. Potency of above ground carbon in Wildlife reserve of KGLTL is 10.71 to 122.10 ton per ha. -

Siam Madu Citrus Seeding in Supporting the Development of Sumatra Citrus Zone

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science PAPER • OPEN ACCESS Siam Madu citrus seeding in supporting the development of Sumatra citrus zone To cite this article: Imelda S Marpaung et al 2021 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 819 012065 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.40.139 on 28/09/2021 at 09:19 2nd International Conference Earth Science And Energy IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 819 (2021) 012065 doi:10.1088/1755-1315/819/1/012065 Siam Madu citrus seeding in supporting the development of Sumatra citrus zone Imelda S Marpaung*, Perdinanta Sembiring, Moral A Girsang, and Tommy Purba Balai Pengkajian Teknologi Pertanian Sumatera Utara *[email protected] Abstract. The purposes of this study were to identify the potency of citrus farming and to recommend citrus seeding development policy in North Sumatra Province. The method used in this study was desk study, and secondary data was analyzing descriptively. Citrus seeding is one of the keys to the success of citrus farming. North Sumatra Province is one of the centers for citrus development in Indonesia. The seed is one of the keys to the success of farming. Currently, citrus development in North Sumatra is still constrained by the availability of seeds. Only a few proportions of the seeds that are currently used by farmers were from local breeders and usually carried out if there was a government program. The shortage of citrus seeds came from outside of North Sumatra Province as the Bangkinang citrus variety which is parent stock source was not guaranteed. -

The Development of Smes in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to Create

The development of SMEs in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to create an agricultural center by using a solid cooperation between local governments, enterprises, and farmers : an application of competitive intelligence for stimulating the growth Sahat Manondang Manullang To cite this version: Sahat Manondang Manullang. The development of SMEs in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to create an agricultural center by using a solid cooperation between local governments, enterprises, and farm- ers : an application of competitive intelligence for stimulating the growth. Economics and Finance. Université Paris-Est, 2008. English. NNT : 2008PEST0246. tel-00468693 HAL Id: tel-00468693 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00468693 Submitted on 31 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris-Est Le développement de PME dans les hautes terres de Bukit Barisan pour créer un Centre Agricole au moyen d'une solide coopération entre autorités locales, entreprises et fermiers - Une application de l'Intelligence Compétitive pour stimuler la croissance. -

Law Enforcement of Smes Licensing in Empowerment of People's Economy Connected to Regional Autonomy in North Sumatra, Indonesia

506 International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2021, 10, 506-516 Law Enforcement of SMEs Licensing in Empowerment of People's Economy Connected to Regional Autonomy in North Sumatra, Indonesia Mukidi1, Nelly Azwarni Sinaga2, Nelvitia Purba3 and Rudy Pramono4,* 1Universitas Islam Sumatera Utara; 2Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Sibolga; 3Universitas Muslim Nusantara Al Washliyah; 4Pelita Harapan University, Indonesia Abstract: law enforcement on SME licensing aims to encourage the empowerment of the people's economy through improving the quality of licensing services in the regional autonomy government and for better chances in the future in North Sumatra Province. The research method used is normative legal research (juridical normative), juridical sociology, and empirical to find the truth related to the enforcement of SME licensing laws that have been stipulated in the regulations. Result of this study, the process for obtaining SME licensing in North Sumatra has been regulated through the One-Stop Integrated Licensing Service Agency based on the Minister of Home Affairs Regulation followed by Governor, Regent, and Mayor regulations through regional regulations. In the implementation, it will be carried out using technology systems and facilities or still manual. From the actual conditions, licensing services are still problematic so that to achieve the goal of law enforcement in empowering the people's economy or even to improve the economy of the community is not yet optimal, because the implementation of regulations has not been implemented properly and correctly so that the people applying for permits still have difficulty obtaining business licenses. From the results of the delegation of the authority of the regional head to the BPPTSP, it has not been fully implemented, there are still other offices that accept delegations so that permit applicants find it difficult and convoluted and their implementation overlaps in the difficult bureaucracy, finally the timeliness and expenditure of costs are not as expected. -

(Manihot Esculenta Crantz) in NORTH SUMATERA

BioLink : Jurnal Biologi Lingkungan, Industri dan Kesehatan, Vol. 7 (1) August (2020) ISSN: 2356- 458X (print) ISSN: 2550-1305 (online) DOI: 10.31289/biolink.v7i1.3405 BioLink Jurnal Biologi Lingkungan, Industri, Kesehatan Available online http://ojs.uma.ac.id/index.php/biolink IDENTIFICATION AND INVENTORY OF CASSAVA (Manihot esculenta Crantz) IN NORTH SUMATERA Emmy Harso Kardhinata1*, Edison Purba2, Dwi Suryanto3, dan Herla Rusmarilin4 1&2Program Study of Agrotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia 3Program Study of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia 4Program Study of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Indonesia Received : 24-09-2019; Reviewed : 24-01-2020: Accepted : 20-02-2020 *Corresponding author: E-mail : [email protected] Abstract The study of identification and inventory of cassava accessions was done from August to September 2014 in four districts based on their potential as a center for cassava cultivation, namely Simalungun, Serdang Bedagai, Deli Serdang, Langkat Regency representing the lowlands and Simalungun and Karo Regency representing the highlands. Each district was selected 3 subdistricts and each subdistrict was surveyed 3 villages randomly through the accidental sampling method. Guidance on identifying morphological characters was used by reference from Fukuda, et al. (2010) by giving a score for each character observed. The results of the study obtained 8 genotypes with their respective codes and local names; 1) Sawit (G1), 2) Lampung (G2), 3) Merah (G3), 4) Adira-1 (G4), 5) Kalimantan (G5), 6) Malaysia (G6), 7) Roti (G7) and 8) Klanting (G8). The most common genotype found in the location were Malaysia and Adira-1, while the rarest was Merah. -

Final Project Report English Pdf 38.05 KB

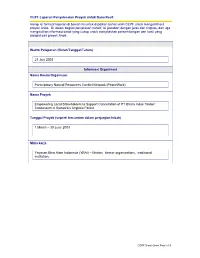

CEPF Laporan Penyelesaian Proyek untuk Dana Kecil Harap isi formulir laporan di bawah ini untuk dijadikan bahan oleh CEPF untuk mengerti hasil proyek Anda. Di dalam bagian penjelasan naratif, isi jawaban dengan jelas dan ringkas, dan uga mengikutkan informasi detail yang cukup untuk menjelaskan perkembangan dan hasil yang didapat dari proyek Anda. Waktu Pelaporan (Bulan/Tanggal/Tahun) 21 July 2003 Informasi Organisasi Nama Resmi Organisasi Participatory Natural Resources Conflict Network (PeaceWork) Nama Proyek Empowering Local Stakeholders to Support Cancellation of PT Bhara Induk Timber Concession in Sumatra’s Angkola Forest Tanggal Proyek (seperti tercantum dalam perjanjian hibah) 1 March – 30 June 2003 Mitra kerja Yayasan Bina Alam Indonesia (YBAI) – Medan, farmer organizations, traditional institution, CEPF Small Grant Final v1.0 Ringkasan Proyek- Jelaskan dengan singkat proyek yang Anda kerjakan. Project entitle "Empowering Local Stakeholders Support Cancellation PT Bhara Induk Timber Concession in Angkola Forest Sumatra' have been conducted from 1 March until 30 June 2003 by PEACEWORK. Project can be divided two main activities that study management of natural forest resources and local stake-holder facilitation. Study focused in conflict of natural forest resources among stake-holder in South Tapanuli Regency and Mandailing Natal Regency. From result of study, is hereinafter conducted by facilitation activity to reach for support in the effort discontinuing operating of PT. Bhara Induk Timber Concession in South Tapanuli Regency. Result of this study is also made the basis for in designing conflict resolution options and future strategy management of related to forest development of conservation corridor of Angkola-Leuser-Seulawah and also become input materials to Minister Forestry and other non-governmental organization. -

Inventarisasi Dan Evaluasi Mineral Non Logam Di Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah Dan Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan , Provinsi Sumatera Utara

INVENTARISASI DAN EVALUASI MINERAL NON LOGAM DI KABUPATEN TAPANULI TENGAH DAN KABUPATEN TAPANULI SELATAN , PROVINSI SUMATERA UTARA Oleh : Nazly Bahar, Umi Kuntjara, Syaiful Asri W. SUBDIT. MINERAL NON LOGAM ABSTRACT Investigated area is in Middle Tapanuli and South Tapanuli Regency, North Sumatra Province. The Geological very complex, consist of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks which age from Permo-Carbon up to Resen. Both of this regency, conducive to have various area mineral commodities, especially non-metallic, which some type prospects to be developed. In Middle Tapanuli it is found granite, clay, limestone, gravel, quartz sand, trass, andesite and dacite. While in South Tapanuli there are granite, clay, limestone, gravel, trass, pumice, slate and quartzite. SARI Lokasi kegiatan terletak di wilayah Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah dan Tapanuli Selatan, Sumatera Utara.Kondisi geologi yang cukup kompleks, dengan jenis batuan yang berumur mulai dari Permo- Karbon sampai dengan Resen, terdiri dari berbagai jenis litologi mulai dari batuan beku, batuan metamorf dan batuan sedimen, memungkinkan kedua daerah kabupaten ini memiliki berbagai jenis bahan galian, terutama non-logam, yang beberapa jenis diantaranya cukup prospek untuk dikembangkan. Di Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah tersebar bahan galian granit, lempung, batugamping, sirtu, pasir/batupasir kuarsa, tras, andesit dan dasit. Sedangkan di Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan terdapat bahan galian granit, lempung, batugamping, sirtu, tras, batuapung, batusabak dan kuarsit. I. PENDAHULUAN daerah otonom kedua Pemerintah Kabupaten tersebut berharap lebih mengetahui potensi 1.1. Latar Belakang sumber daya mineral di daerah masing- Dalam rangka pelaksanaan kegiatan masing, sehingga dapat dikelola seefisien Inventarisasi dan Evaluasi Sub Tolok Ukur mungkin untuk sebesar-besarnya kepentingan Mineral Non Logam, Proyek Inventarisasi dan masyarakatnya. -

Institutional System and Rice Seed Group Problems in North Sumatra Province

Institutional System and Rice Seed Group Problems in North Sumatra Province Muhammad Asa’ad, Tri Martial, Surya Dharma and Desi Novita Agribusiness Department, Faculty of Agriculture, UISU, Medan, Indonesia Keywords: Institutional, Seeds, Rice Fields, Breeding Groups. Abstract: This study aims to identify the institutional forms of breeders of paddy rice and identify problems that occur in rice seed breeding groups in North Sumatra. This study uses in-depth interview method with key respondents. Besides, questionnaires and observations were made in the field. The results showed that the form of breeding institutions consist of two independent and non-independent breeders. All breder members only carry out seed production activities on cultivation resistance, while post-harvest activities, certification and marketing are carried out by the head of the farmer group or the partner company. Problems faced by breeders include lack of access to irrigation sources, capital sources, markets, lack of knowledge and skills in post-harvest and certification and high dependence on one party. 1 INTRODUCTION Whatever the source, farmers are generally very aware of the need to sow the seeds of the highest The Agriculture Sector, especially the food crops quality available. But that does not mean they prefer sub-sector is one of the fields that has great potential "official seeds" rather than those from local sources. and is important to be developed in North Sumatra Farmers' priorities related to quality are more Province. Therefore, agricultural development fulfilled from local sources. The genetic quality of policies, especially sub-sectors of the food crops are the varieties circulated may not be adapted to the directed to ensure food security to support national conditions of the local agricultural environment as security. -

General Information

GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF SEAPAC 23 -24 October 2013 Medan, North Sumatera – Indonesia 1. Meeting Information Tuesday, - Arrival of delegates 22 October 2012 2.00 – 6.00 pm Registration 7.00 pm Quiet Dinner th Venue : the Kitchen Restaurant, 9 Floor, Aryaduta Hotel Wednesday, 8.00 am Registration 23 October 2013 9.00 am Opening Session Venue: Ballroom 2 10.45 am – FIRST SESSION OF THE SEAPAC 13.00pm GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 2.00 pm -5.30 SECOND SESSION OF THE SEAPAC pm GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 6.30 pm Dinner Thursday, 9.00 am Presentation and Debate (continued) 24 October 2013 10.45 am THIRD SESSION OF THE SEAPAC GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 12.30 am Luncheon 2.30 pm FOURTH SESSION OF THE SEAPAC GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 Friday, - Departure of Delegates 25 October 2012 2. Social Function Wednesday, 6.30 pm Dinner hosted by Chairman of SEAPAC/Speaker 23 October 2013 of the Indonesian House of Representatives, H.E Dr. Marzuki Alie Venue:Marriot Hotel Dress Code: National Dress Thursday, 12.30 pm Luncheon hosted by Chairman of Indonesian 24 October 2013 GOPAC National Chapter, Hon. Dr. Pramono Anung Wibowo Venue: The Heritage, Grand Aston, Hotel Dress Code: Business Suit 7.00 pm Farewell Dinner hosted by Governor of North Sumatera Venue: tbc Dress Code: National Dress 3. Date and Venue of Meeting The General Assembly of the Southeast Asia Parliamentarians Against Corruption (SEAPAC) will take place at Aryaduta Hotel, Medan - North Sumatera, Indonesia from Wednesday, 23 October 2013 to Thursday, 24 October 2013. -

Long Range Urban Development Plan

S REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA MINISTRY OF PUBLIC WORKS DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF HOUSING BUILDING PLANNING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (CIFTA KARYA) MEDAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT, HOUSING, WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION PROJECT VOLUME III LONG RANGE URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN OCTOBER 1980 ENGINEERING-SCIENCE, INC. SINOTECH ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, INC. A JOINT VENTURE in association with PADCO and P.T. DACREA PREFACE The feasibility reports emanating from the Medan Urban Development, Housing, Water Supply and Sanitation Project were submitted in draft form to the Government of Indonesia (GOI) in February 1980. These reports, together with the earlier master plan reports, were reviewed by GOI in July 1980 and discussed with the Consultant at a series of meetings at that time. The outcome of this review process was that certain changes in content and format were agreed. These changes have been incorporated into the final printed reports. A result of adopting the new guidelines provided by GOI is that differences occur between the Repelita III investments proposed in the master plan studies and those contained in the first stage program recommendations. The latter incorporate the final adjustments and represent the recommended program for Repelita III. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF TABLES ORGANIZATION OF PROJECT REPORTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.1 GENERAL 1-1 1.2 NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT 1-2 1.3 THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR MEDAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT 1-3 1.4 MAJOR CONCLUSIONS 1-3 1.5 FUTURE PROSPECTS 1-4 1.6 THE BASIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY