Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Allocation of Dividend of the Regional Government-Owned

European Research Studies Journal Volume XX, Issue 4B, 2017 pp. 244-259 The Effect of Allocation of Dividend of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises and the Empowerment Efforts on the Revenue of Regional Government: The Case of Indonesia Iskandar Muda1 Abstract: The purpose of this study is to find out the factors influencing the increase in the dividend of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises (BUMD) in North Sumatera Province. In addition, it is also to determine the steps and efforts in empowering and improving the capacity of BUMD in increasing the allocation of dividend to the Regional Government of North Sumatera. It is an explanatory survey study, a study which justifies the relationship between the independent and dependent variables and explains the relationship. This study used survey for its research design. The data used in this study are primary and secondary data. The population of this study is the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises of North Sumatera Province. The samples were taken by using purposive sampling method with the stakeholders of the Regional Government-Owned Enterprises of North Sumatera Province being PT. Bank Sumut, PT. Kawasan Industri Medan, PT Perkebunan Sumut, PT. Askrida and PT. Dirga Surya as the respondents, 66 in total. The method used in this study is the Descriptive Quantitative method with Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) by using AMOS as the analytical tool. For the analysis of perception, this study used SPSS for the statistics. This study concluded that (1) The factors of Equity Capital (Penyertaan Modal) and Other Legitimate Local/Regional Government Revenue of Provinces and Districts/Cities can increase the sources of Local/Regional Government Revenue. -

The Development of Smes in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to Create

The development of SMEs in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to create an agricultural center by using a solid cooperation between local governments, enterprises, and farmers : an application of competitive intelligence for stimulating the growth Sahat Manondang Manullang To cite this version: Sahat Manondang Manullang. The development of SMEs in Bukit Barisan High Land Area to create an agricultural center by using a solid cooperation between local governments, enterprises, and farm- ers : an application of competitive intelligence for stimulating the growth. Economics and Finance. Université Paris-Est, 2008. English. NNT : 2008PEST0246. tel-00468693 HAL Id: tel-00468693 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00468693 Submitted on 31 Mar 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris-Est Le développement de PME dans les hautes terres de Bukit Barisan pour créer un Centre Agricole au moyen d'une solide coopération entre autorités locales, entreprises et fermiers - Une application de l'Intelligence Compétitive pour stimuler la croissance. -

Final Project Report English Pdf 38.05 KB

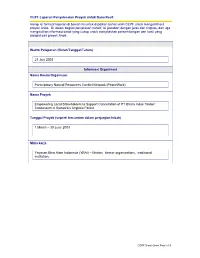

CEPF Laporan Penyelesaian Proyek untuk Dana Kecil Harap isi formulir laporan di bawah ini untuk dijadikan bahan oleh CEPF untuk mengerti hasil proyek Anda. Di dalam bagian penjelasan naratif, isi jawaban dengan jelas dan ringkas, dan uga mengikutkan informasi detail yang cukup untuk menjelaskan perkembangan dan hasil yang didapat dari proyek Anda. Waktu Pelaporan (Bulan/Tanggal/Tahun) 21 July 2003 Informasi Organisasi Nama Resmi Organisasi Participatory Natural Resources Conflict Network (PeaceWork) Nama Proyek Empowering Local Stakeholders to Support Cancellation of PT Bhara Induk Timber Concession in Sumatra’s Angkola Forest Tanggal Proyek (seperti tercantum dalam perjanjian hibah) 1 March – 30 June 2003 Mitra kerja Yayasan Bina Alam Indonesia (YBAI) – Medan, farmer organizations, traditional institution, CEPF Small Grant Final v1.0 Ringkasan Proyek- Jelaskan dengan singkat proyek yang Anda kerjakan. Project entitle "Empowering Local Stakeholders Support Cancellation PT Bhara Induk Timber Concession in Angkola Forest Sumatra' have been conducted from 1 March until 30 June 2003 by PEACEWORK. Project can be divided two main activities that study management of natural forest resources and local stake-holder facilitation. Study focused in conflict of natural forest resources among stake-holder in South Tapanuli Regency and Mandailing Natal Regency. From result of study, is hereinafter conducted by facilitation activity to reach for support in the effort discontinuing operating of PT. Bhara Induk Timber Concession in South Tapanuli Regency. Result of this study is also made the basis for in designing conflict resolution options and future strategy management of related to forest development of conservation corridor of Angkola-Leuser-Seulawah and also become input materials to Minister Forestry and other non-governmental organization. -

Inventarisasi Dan Evaluasi Mineral Non Logam Di Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah Dan Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan , Provinsi Sumatera Utara

INVENTARISASI DAN EVALUASI MINERAL NON LOGAM DI KABUPATEN TAPANULI TENGAH DAN KABUPATEN TAPANULI SELATAN , PROVINSI SUMATERA UTARA Oleh : Nazly Bahar, Umi Kuntjara, Syaiful Asri W. SUBDIT. MINERAL NON LOGAM ABSTRACT Investigated area is in Middle Tapanuli and South Tapanuli Regency, North Sumatra Province. The Geological very complex, consist of igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks which age from Permo-Carbon up to Resen. Both of this regency, conducive to have various area mineral commodities, especially non-metallic, which some type prospects to be developed. In Middle Tapanuli it is found granite, clay, limestone, gravel, quartz sand, trass, andesite and dacite. While in South Tapanuli there are granite, clay, limestone, gravel, trass, pumice, slate and quartzite. SARI Lokasi kegiatan terletak di wilayah Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah dan Tapanuli Selatan, Sumatera Utara.Kondisi geologi yang cukup kompleks, dengan jenis batuan yang berumur mulai dari Permo- Karbon sampai dengan Resen, terdiri dari berbagai jenis litologi mulai dari batuan beku, batuan metamorf dan batuan sedimen, memungkinkan kedua daerah kabupaten ini memiliki berbagai jenis bahan galian, terutama non-logam, yang beberapa jenis diantaranya cukup prospek untuk dikembangkan. Di Kabupaten Tapanuli Tengah tersebar bahan galian granit, lempung, batugamping, sirtu, pasir/batupasir kuarsa, tras, andesit dan dasit. Sedangkan di Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan terdapat bahan galian granit, lempung, batugamping, sirtu, tras, batuapung, batusabak dan kuarsit. I. PENDAHULUAN daerah otonom kedua Pemerintah Kabupaten tersebut berharap lebih mengetahui potensi 1.1. Latar Belakang sumber daya mineral di daerah masing- Dalam rangka pelaksanaan kegiatan masing, sehingga dapat dikelola seefisien Inventarisasi dan Evaluasi Sub Tolok Ukur mungkin untuk sebesar-besarnya kepentingan Mineral Non Logam, Proyek Inventarisasi dan masyarakatnya. -

Institutional System and Rice Seed Group Problems in North Sumatra Province

Institutional System and Rice Seed Group Problems in North Sumatra Province Muhammad Asa’ad, Tri Martial, Surya Dharma and Desi Novita Agribusiness Department, Faculty of Agriculture, UISU, Medan, Indonesia Keywords: Institutional, Seeds, Rice Fields, Breeding Groups. Abstract: This study aims to identify the institutional forms of breeders of paddy rice and identify problems that occur in rice seed breeding groups in North Sumatra. This study uses in-depth interview method with key respondents. Besides, questionnaires and observations were made in the field. The results showed that the form of breeding institutions consist of two independent and non-independent breeders. All breder members only carry out seed production activities on cultivation resistance, while post-harvest activities, certification and marketing are carried out by the head of the farmer group or the partner company. Problems faced by breeders include lack of access to irrigation sources, capital sources, markets, lack of knowledge and skills in post-harvest and certification and high dependence on one party. 1 INTRODUCTION Whatever the source, farmers are generally very aware of the need to sow the seeds of the highest The Agriculture Sector, especially the food crops quality available. But that does not mean they prefer sub-sector is one of the fields that has great potential "official seeds" rather than those from local sources. and is important to be developed in North Sumatra Farmers' priorities related to quality are more Province. Therefore, agricultural development fulfilled from local sources. The genetic quality of policies, especially sub-sectors of the food crops are the varieties circulated may not be adapted to the directed to ensure food security to support national conditions of the local agricultural environment as security. -

General Information

GENERAL INFORMATION GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF SEAPAC 23 -24 October 2013 Medan, North Sumatera – Indonesia 1. Meeting Information Tuesday, - Arrival of delegates 22 October 2012 2.00 – 6.00 pm Registration 7.00 pm Quiet Dinner th Venue : the Kitchen Restaurant, 9 Floor, Aryaduta Hotel Wednesday, 8.00 am Registration 23 October 2013 9.00 am Opening Session Venue: Ballroom 2 10.45 am – FIRST SESSION OF THE SEAPAC 13.00pm GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 2.00 pm -5.30 SECOND SESSION OF THE SEAPAC pm GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 6.30 pm Dinner Thursday, 9.00 am Presentation and Debate (continued) 24 October 2013 10.45 am THIRD SESSION OF THE SEAPAC GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 12.30 am Luncheon 2.30 pm FOURTH SESSION OF THE SEAPAC GENERAL ASSEMBLY Venue: Ballroom 2 Friday, - Departure of Delegates 25 October 2012 2. Social Function Wednesday, 6.30 pm Dinner hosted by Chairman of SEAPAC/Speaker 23 October 2013 of the Indonesian House of Representatives, H.E Dr. Marzuki Alie Venue:Marriot Hotel Dress Code: National Dress Thursday, 12.30 pm Luncheon hosted by Chairman of Indonesian 24 October 2013 GOPAC National Chapter, Hon. Dr. Pramono Anung Wibowo Venue: The Heritage, Grand Aston, Hotel Dress Code: Business Suit 7.00 pm Farewell Dinner hosted by Governor of North Sumatera Venue: tbc Dress Code: National Dress 3. Date and Venue of Meeting The General Assembly of the Southeast Asia Parliamentarians Against Corruption (SEAPAC) will take place at Aryaduta Hotel, Medan - North Sumatera, Indonesia from Wednesday, 23 October 2013 to Thursday, 24 October 2013. -

Jurnal Ilmiah Maksitek Issn. 2655-4399

JURNAL ILMIAH MAKSITEK Vol. 5 No. 3 ISSN. 2655-4399 September 2020 THE REVITALIZATION OF BATAKNESE LANGUAGE IN TANJUNG BALAI : A STUDY CASE AT SEI TUALANG RASO TANJUNG BALAI, NORTH SUMATERA RANI FAIRUS SEKOLAH TINGGI EKONOMI AL-HIKMAH [email protected] Abstract-The study was conducted to find out the revitalization of Bataknese language in Tanjung Balai. The subject of the study was 123 households in three streets in Sei Tualang Raso subdistrict, Tanjungbalai city. This research design was qualitative descriptive design. The instrument for collecting the data was questionnaire. The data was analyzed by reading the result of questionnaires which have been filled by respondents. The result of analysis showed that: 1) Increase the proficiency speakers of Bataknese language. The skill of the language proficiency includes listening, speaking, reading and writing. (2) Grow positive attitude towards bataknese language. (3) Expand the use of bataknese language distribution. Spreading the use of bataknese language can be done by means of print, electronic, device cyberspace. Keywords: Bataknese, History of Bataknese, and Revitalization INTRODUCTION Language revitalization can be viewed as a form of language policy that seeks to halt and reverse this process of shift: different policy measures are adopted with the aim of ensuring that a vulnerable language community does not decline and disappear, but rather demonstrates 'a new-found vigour' (Paulston, 1993: 279). This, it is claimed, will occur when policy steps successfully address a range of -

The Impact of Tourism Industry on Economic Growth in the Salumpat Saindege City (Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatera)

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-2S9, September 2019 The Impact of Tourism Industry on Economic Growth in the Salumpat Saindege City (Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatera) Enni Sari Siregar, Farida Aini, Nora Zulvianti city is a crossing of land routes to the cities of Medan, Abstract: This article focused on analyze the Impact of the Sibolga, and Padang (West Sumatra) in the west Sumatra Tourism Industry on Economic Growth in the Salumpat route. The topography of the area is in the form of a valley Saindege City (Padangsidimpuan, North Sumatera). This article surrounded by Bukit Barisan, so that when viewed from afar, is a descriptive study with a library study approach. Data used the city of Padang Sid is like a lake that resembles a lake. The time series of 2005 - 2017. The results of research concluded highest peak of the hills and mountains surrounding this city that the value of tcount is 0.443. By using a 95% confidence level α = 0.05 compared with the sig value obtained at 0.667, the sig is Mount Lubuk Raya and Bukit (Tor) Sanggarudang which value is greater than α or 0.667 > 0.05. This shows that tourism are located side by side to the north of the city. One of the is not significantly and positive effect on the economic growth in famous hilltops in Padangsidimpuan is Bukit (Tor) Salumpat Saindege City and this indicates that the Economic Simarsayang. Such a topographical situation clearly invites Growth in the Salumpat Saindege City (Padangsidimpuan North some public interest to enjoy the beautiful views of Salumpat Sumatera) is not determined by the Tourism sector in the same direction. -

Analisis Klassen Typology Dan Williamson Index)

POLA PERTUMBUHAN EKONOMI DAN TINGKAT KETIMPANGAN PEMBANGUNAN EKONOMI ANTAR KABUPATEN/KOTA (Analisis Klassen Typology Dan Williamson Index) Pangeran Dosen Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Graha Kirana Abstract This study aims to determine the pattern of economic growth between districts / cities and the level of economic development inter-regency / city in North Sumatra Province. This research uses Klassen Typology analysis and Williamson Index analysis. Typology Klassen Analysis Results show that in the period 2010-2012 and the period 2013- 2015, districts / cities that remain in quadrant I are South Tapanuli Regency, North Labuhanbatu Regency, Pematangsiantar City, Medan City, and Binjai City. Regencies / cities that remain in quadrant II are Toba Samosir Regency, Labuhanbatu Regency, Simalungun Regency, Karo Regency, and Batu Bara Regency. Regencies / cities that remain in quadrant III are Nias Regency, Mandailing Natal Regency, Pakpak Bharat Regency, Padang Lawas Regency, North Nias Regency, Gunungsitoli City. Regencies / cities that remain in quadrant IV are Central Tapanuli Regency, North Tapanuli Regency, Dairi Regency, South Nias Regency, Humbang Hasundutan Regency, and Padangsidimpuan City. Williamson Iindex analysis shows the average value of IW among regencies / cities in North Sumatra Province is relatively high at 0.4316. This means that the value of inequality in economic development between regencies / cities in North Sumatra Province is very high. Keywords: Economic Growth, Economic Development Inequality, Klassen Typology, -

Analysis of Factors Affecting the Human Development Index in North Sumatra Province

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 19, Issue 10. Ver. VII. (October. 2017), PP 27-36 www.iosrjournals.org Analysis of Factors Affecting the Human Development Index in North Sumatra Province Asmita1*, Fitrawaty2, Dede Ruslan3 1 Master Program, State University of Medan. Indonesia 2Faculty of Economics, State University of Medan. Indonesia 3Faculty of Economics, State University of Medan. Indonesia * Related Authors: [email protected] Abstract: This research aims to analyze the influence of economic growth, percentage of poor population, government expenditure of education, health expenditure of government, and income distribution inequality affecting human development index (HDI) in North Sumatera Province. This research uses panel data analysis model through fixed effect model approach. Sources of data used in the form of secondary data obtained from the publication data of the Central Statistics Indonesia (BPS) and data Ministry of Finance with the period 2009-2013, with data between 33 districts/cities. The results of this study indicate that of the five variables suspected to affect HDI in the Province of North Sumatra, assuming ceteris paribus condition that: Economic growth has a significant positive effect on HDI due to the increase of economic growth of 0,000000293. The percentage of poor people does not affect to the HDI. Government expenditures in the field of education have no effect on HDI. Government expenditures in the field of health have a significant positive effect on HDI and income inequality has no effect. Key words : HDI, Economic Growth, IW, Education Fund, Health Fund and Percentage of the poor, Fixed Effects Model, North Sumatera Province ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 04-10-2017 Date of acceptance: 28-10-2017 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. -

Agrarian Conflicts Plantations in North Sumatera

Agrarian Conflicts Plantations in North Sumatera Hidayat1, Ichwan Azhari2, Samsidar Tanjung3 {[email protected]} Department of History, Faculty of Social Science, Universitas Negeri Medan, Indonesia1,2,3 Abstract. Plantation agrarian conflict is an agrarian conflict that is quite prominent in the area which is the center of plantations in north Sumatra. Agrarian conflicts can analyze from Marxian and Weberian perspectives. The agrarian conflict in North Sumatra in the period 1970-2000 the quantity and quality was the biggest agrarian conflict outside of Java. The agrarian conflict in North Sumatra, is caused by the development and expansion of plantation businesses; development of conservation and protection forests; development of transmigration areas, and an increase in people who are "hungry for land" as a result of life difficulties, narrowing of employment opportunities in both the formal and informal sectors and the rise in layoffs. The agrarian conflicts of plantations in North Sumatra can be identified as follows: agrarian conflicts arise because of the government's denial of people's socio-economic rights; related to the effort of unilateral manipulation and interpretation of the government and capital owners regarding the State's Right to Control over land, use of instruments criminal law, intimidation and violence through the mobilization of the apparatus against the people who fight and claim their rights to land and in every agrarian conflict, the community is on the weak side and has no bargaining. Keywords: agrarian conflict, plantations, hungry for land, government's denial 1 Introduction Agrarian conflicts in Indonesia in the last three decades have tended to become more widespread and intensive in terms of both quantity and quality. -

Tetrahedron Template

Journal of Research in Weed Science Volume 3 Issue 1 (2020), pp 24-35 Journal of Research in Weed Science Journal homepage: www.jrweedsci.com Original Research Article Single and Multiple Resistance of Eleusine indica from Asahan Regency, Indonesia Koko Tampubolon a,* , Wismaroh Sanniwati Saragih a,b, Zavandri Purba c, Ikhlas Hamzani d a Doctoral Program of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, 20155, Indonesia. b Program Study of Agrotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Pembinaan Masyarakat Indonesia. c Program Study of Agrotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, 20155, Indonesia. d Program Magister of Agrotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, 20155, Indonesia. ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Eleusine indica population at oil palm estate in the Asahan Regency has never Received: 1 June 2019 been reported to being resistant to glyphosate and paraquat. This research was Revised: 30 June 2019 aimed to the resistance classification of E. indica population to glyphosate from one of oil palm estate in the Asahan Regency and to find out of glyphosate- Accepted: 1 July 2019 resistant Eleusine (GRE) biotype has been also resistant to paraquat. This Available online: 2 July 2019 research was conducted on Weed Research Center Land, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan from September 2017 until May 2018. DOI: 10.26655/JRWEEDSCI.2020.1.3 Single resistance evaluation of E. indica population was performed using glyphosate at the dose 720 g a.i.ha-1. However the multiple resistance of GRE KEYWORDS biotype was performed using paraquat at rates of 0, 50, 100, 200, and 400 g a.i.ha-1 and glyphosate at rates of 0, 720, 1440, 2880, and 5760 g a.i.ha-1.