Apocalyptic Desire and Our Urban Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sessões Recomendadas Para Crianças L São, Além Das INFANTIS: FUTURO ANIMADOR E ANIMATV

PETROBRAS apresenta k'FTUJWBM*OUFSOBDJPOBM EF"OJNB}{PEP#SBTJM 3JPEF+BOFJSP BEF+VMIP Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Centro Cultural Correios Casa França-Brasil Oi Futuro Cinema Odeon-BR Unibanco Arteplex Botafogo 4P1BVMP EF+VMIPBnEF"HPTUP Memorial da América Latina Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil 1 ATENÇÃO: Anima Mundi informa que as sessões recomendadas para crianças L são, além das INFANTIS: FUTURO ANIMADOR e ANIMATV. 14 As demais sessões não são recomendadas para menores de 14 anos. RIO DE JANEIRO Locais De Exibição Obs: Pagam meia-entrada: maiores de 60 (sessenta) anos e crianças até 12 (doze) anos. Centro Cultural Casa França-Brasil Banco do Brasil (CCBB) Rua Visconde de Itaboraí, 78, Centro Rua Primeiro de Março, 66, Centro Informações: (21) 2332-5121 Informações: (21) 3808-2020 Horário de funcionamento: Horário de funcionamento: 10h às 21h Estúdio Aberto: Ter a Dom 13h às 19h, Ingresso: R$ 6,00 (meia entrada R$ 3,00) Entrada franca Sessões gratuitas: Infantis, AnimaTV e Futuro Animador, retirada de senhas somente no dia da sessão Unibanco Arteplex Botafogo com 1 hora de antecedência na bilheteria Praia de Botafogo, 316 Térreo, Botafogo Informações: (21) 2559-8750 Centro Cultural Correios Horário de funcionamento: 12h às 22h Rua Visconde de Itaboraí, 20, Centro Ingresso: R$ 6,00 (meia entrada: R$ 3,00), Informações: (21) 2253-1580 Vendas por dia, a partir da abertura da bilheteria Horário de funcionamento: 11h30 às 19h30 Oi Futuro Flamengo · Sala de Cinema Rua Dois de Dezembro, 63, Flamengo Entrada Franca, Classificação Livre, Informações: -

Ca' Foscari Short Film Festival 7

Short ca’ foscari short film festival 7 1 15 - 18 MARZO 2017 AUDITORIUM SANTA MARGHERITA - VENEZIA INDICE CONTENTS × Michele Bugliesi Saluti del Rettore, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia × Michele Bugliesi Greetings from the Rector, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Flavio Gregori Saluti del Prorettore alle attività e rapporti culturali, × Flavio Gregori Greetings from the Vice Rector for Cultural activities and relationships, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Board × Board × Ringraziamenti × Acknowledgements × Comitato Scientifico × Scientific Board × Giuria Internazionale × International Jury × Catherine Breillat × Catherine Breillat × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Barry Purves × Barry Purves × Giuria Levi Colonna Sonora × Levi Soundtrack Jury × Concorso Internazionale × International Competition × Concorso Istituti Superiori Veneto × Veneto High Schools’ Competition × Premi e menzioni speciali × Prizes and special awards × Programmi Speciali × Special programs × Concorso Music Video × Music Video Competition × Il mondo di Giorgio Carpinteri × The World of Giorgio Carpinteri × Desiderio in movimento - Tentazioni di celluloide × Desire on the move - Celluloid temptations × Film making all’Università Waseda × Film-making at Waseda University Waseda Students Waseda Students Il mondo di Hiroshi Takahashi The World of Hiroshi Takahashi × Workshop: Anymation × Workshop: Anymation × Il mondo di Iimen Masako × The World of Iimen Masako × C’era una volta… la Svizzera × Once upon a time… Switzerland -

Catálogo De Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX

European and Latin American short film market Catálogo de Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX Bienvenidos / Welcome .................................................... 3 Programa Shortlatino / Shortlatino program ............. 5 PAÍSES EUROPEOS / EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PAÍSES LATINOS / LATIN COUNTRIES Alemania / Germany ........................................................ 11 Argentina / Argentina .................................................. 299 Austria / Austria .............................................................. 40 Brasil / Brazil .................................................................. 303 Bélgica / Belgium ............................................................. 41 Chile / Chile ................................................................... 309 Bulgaria / Bulgaria ......................................................... 49 Colombia / Colombia ...................................................... 311 Dinamarca / Denmark .................................................... 50 Costa Rica / Costa Rica ................................................ 315 Eslovenia / Slovenia ........................................................ 51 Cuba / Cuba ..................................................................... 316 España / Spain ................................................................. 52 México / Mexico ............................................................... 317 Estonia / Estonia ........................................................... 168 Perú / Peru .................................................................... -

Tidligere Vindere 1975-2012

I dette dokument kan du finde tidligere vindere af Odense Internationale Film Festival. Derudover kan du se, hvem der var jury det pågældende år samt læse en kort beskrivelse af de enkelte festivaler. Følg hyperlinksene herunder for at komme frem til det ønskede år: 1975, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 Hvis du har spørgsmål, er du altid velkommen til at kontakte os på telefon 6551 2837 eller på mail [email protected] 1975, 27. juli – 4. august I 1975 afholdes festivalen for første gang under navnet Den Internationale Eventyrfestival. Festivalen kunne præsentere 58 udvalgte film fra 20 forskellige lande. Filmene blev vist i Palace Biografen. Juryen bestod af: - Jan Lenica, Polen - Thorbjørn Egner, Norge - Georg Poulsen, Danmark - Niels Oxenvad, Danmark - Ebbe Larsen, Danmark 1.pris - Guldpris THE THREE COMPANIONS af Jan Karpas, Tjekkoslovakiet THE LEGEND OF POUL BUNYAN af Sam Weiss, USA 2.pris - Sølvpris THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL af Kazuhiko Watanabe, Japan Vinderfilm THE FROG PRINCE af Jim Henson, USA THE SHADOW af Jørgen Vestergaard, Danmark THE SWINEHERD af Gene Deitch, Danmark ARROW TO THE SUN af Gerald McDermott, USA BLACK OR WHITE af Waclaw Wajser, Polen Personlige priser Thorbjørn Egner: THE BAG OF APPLES af Vladimir Bordzilovskij, U.S.S.R. Speciel Jurypris: THE SERIES OF CARTOONS af Raoul Servais, Belgien 1977, 31. juli - 7. august Den 2. Internationale Eventyrfestival bød på 68 film fra 18 forskellige lande. Filmene blev vist i Palads Teatret, Bio Centret, Folketeatret Grand og Bio Vollsmose. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

Courts-Metrages

COURTS-METRAGES vieux dessins animés libres de droits (Popeye, Tom et Jerry, Superman…) : https://archive.org/details/animationandcartoons page d’accueil (adultes et enfants (films libres de droit) : https://www.apar.tv/cinema/700-films-rares-et-gratuits-disponibles-ici-et-maintenant/ page d’accueil : https://films-pour-enfants.com/tous-les-films-pour-enfants.html page d’accueil : https://creapills.com/courts-metrages-animation-compilation-20200322 SELECTION Un film pour les passionnés de cyclisme et les nostalgiques des premiers Tours de France. L'histoire n'est pas sans rappeler la réelle mésaventure du coureur cycliste français Eugène Christophe pendant la descente du col du Tourmalet du Tour de France 1913. Eugène Christophe cassa la fourche de son vélo et marcha 14 kilomètres avant de trouver une forge pour effectuer seul la réparation, comme l'imposait le règlement du Tour. Les longues moustaches du héros sont aussi à l'image d'Eugène Christophe, surnommé "le Vieux Gaulois". (7minutes , comique) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/14.html pickpocket Une course-poursuite rocambolesque. (1minute 27) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/korobushka.html salles gosses (1 minutes 30) Oui, les rapaces sont des oiseaux prédateurs et carnivores ! Un film comique et un dénouement surprenant pour expliquer aux enfants l'expression "être à bout de nerfs". https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/sales-gosses.html i am dyslexic (6 minutes 20) Une montagne de livres ! Une très belle métaphore de la dyslexie et des difficultés que doivent surmonter les enfants dyslexiques. https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/i-am-dyslexic.html d'une rare crudité et si les plantes avaient des sentiments (7 minutes 45) Un film étrange et poétique, et si les plantes avaient des sentiments. -

Oficina De Animação

autoria | MARIA NUNES ANIMAÇÃO TÉCNICAS E HISTÓRIA primeira edição SETEMBRO 2016 A infância vive a realidade da única forma honesta, que é tomando-a como uma fantasia. Agustina Bessa-Luís UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Orientação | Francisco Merino “OFICINA DE ANIMAÇÃO - Técnicas e História” Texto | Maria Nunes Design | Maria Nunes Projecto desenvolvido no âmbito de: Ilustrações | Maria Nunes Mestrado de Design Multimédia Setembro de 2016 Impressão e acabamento | Gráfica Maiadouro © todos os direitos reservados 1994 “O Rei Leão” 8 INTRODUÇÃO 10 O QUE É A ANIMAÇÃO? 12 BRINQUEDOS ÓTICOS 15 ANIMAÇÃO TRADICIONAL 19 STOP-MOTION 23 ANIMAÇÃO DE RECORTES 27 PIXILATION 31 ANIMAÇÃO DIRETA 33 ROTOSCOPIA 35 ANIMAÇÃO DIGITAL 38 EVOLUÇÃO DA ANIMAÇÃO INTRODUÇÃO A animação é uma atividade que existe há mais de 100 anos! Ao longo dos anos, várias técnicas e estilos de animação foram desenvolvidos por imensos artistas e animadores. Ao longo deste livro vais aprender o que é a animação, como é que ela funciona, várias maneiras de fazer desenhos animados e alguns dos principais filmes de animação que existem (alguns até já deves conhecer muito bem). 8 Enquanto lês e aprendes, podes experimentar, ao mesmo tempo, algumas das coisas que te são explicadas para ser mais divertido! Podes fazer os teus próprios desenhos animados com as tuas personagens únicas e histórias incríveis. Põe a tua imaginação a funcionar e diverte-te! 9 O QUE É A ANIMAÇÃO? Todos nós já vimos desenhos O QUE É A PERSISTÊNCIA animados e filmes de animação, RETINIANA? mas será que sabemos o que é que torna a animação possível? Sabes A persistência retiniana é um pro- quais são os fenómenos que per- cesso que ocorre numa das partes mitem que vários desenhos formem do olho. -

Shock the Monkey a Vr Film by Nicolas Blies & Stéphane Hueber-Blies

SHOCK THE MONKEY A VR FILM BY NICOLAS BLIES & STÉPHANE HUEBER-BLIES An experiment of anticipation in virtual reality on the privatization of our imagination. Will you be able to regain your freedom? A production by “The advertising industry that is used to create consumers is a phenomenon that has developed in the freest countries. 100 years ago, it became clear that it would be more difficult to control the population by force. The freedom gained was far too great. We needed new ways to control people. With this new objective, the advertising industry exploded to make consumers. The idea is to control everyone, to transform society into a perfect system. A system based on a duo. This duo is you and television, or today, you and the Internet, that shows you what an ideal life looks like, what you should have. And you will spend your time and energy to get it. (...) We create desires, we lock the population into the role of consumers. (...) Consumers who must be spectators, not participants in our democracies. Noam Chomsky “ 2 SUMMARY 2046. SOMA is an activist against the dominant system. It is also the code name for the spirit liberation program she and her team have been running for several months. A program that seeks to stem the privatization of our minds by multinationals and consumerist ideology. SOMA kidnaps you and encourages you to free yourself from this conditioning. With your permission, she infiltrates your brain. You then begin a psychedelic journey into the depths of your imagination to allow you to regain your free will. -

22 VII. the New Golden Age Then Something Wonderful Happened. Just When Everything Was Looking As Grim As It Could for the Art O

VII. The New Golden Age Then something wonderful happened. Just when everything was looking as grim as it could for the art of animation, technology came to the rescue. Here was an art form born only because technology made it possible, almost died when the human costs in time and effort became too high, and now was rescued by technology again. The computer age saved animation. Since computers first came on the scene in the 50s, there have been people who have tried to create machinery and programs to make animation faster, easier and cheaper to both make and distribute. From machines like copiers and scanners, to computers that can draw and render, to the distribution of animation by cable, Internet, phones, tablets and video games - as one character says, “To infinity and beyond” - animation has been totally reborn. As the old animators of the Golden Age were dying off, the new technologies created a huge demand for the old craft. Fortunately, many of the old men were able to pass on their skills to a younger generation, which has helped the quality of today's animation meet and exceed the animation of the Golden Age. In 1985, Girard and Maciejewski at OSU publish a paper describing the use of inverse kinematics and dynamics for animation.! The first live-action film to feature a complete computer-animated character is released, "YOUNG SHERLOCK HOLMES."! Ken Perlin at NYU publishes a paper on noise functions for textures. He later applied this technique to add realism to character animations. In 1986, "A GREEK TRAGEDY" wins the Academy Award. -

Festival Runway, Limp Into the Air (Barely Missing the Trees) and Splutter up Into the Clouds

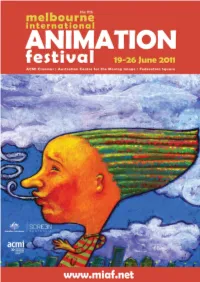

1 DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE Malcolm Turner Greetings to fans, first-timers and the animatedly curious. DIRECTOR Despite the crazed improbability of it all, MIAF is still here doing its thing. It certainly suffers from the so-called ‘bumble bee’ syndrome. That is to say, on paper there’s no way Melbourne International you can prove it will fly. Somehow though, Air MIAF has found a way to bump down the Animation Festival runway, limp into the air (barely missing the trees) and splutter up into the clouds. Dunno how we do it, to be honest. It certainly wouldn’t happen without the support of ACMI, Screen Australia and each and every one of the sponsors. Nor would it happen without the core crew who give up a great deal of their time and varying slivers of their sanity to make this thing work. And it definitely wouldn’t happen without the filmmakers. It surprises alot of people (including me sometimes) just how many short animated films are being made. We get over 2,000 entries every year and the vast majority of them are made for the simple reason that somebody has felt compelled to create them – in much the same way that a painter feels compelled to paint a picture or a playwright feels compelled to create an imaginary universe, populated with a fictional tribe who have something on their mind they want to share. Animation, as a technological achievement, surrounds us and is woven into so many elements of our daily lives. It is a workhorse technology that is pressed into service by any number of plump jockeys who vie for our scarce and shattered attentions as we go through our day. -

Branding the Authentic

INTRODUCTION BRANDING THE AUTHENTIC If there is, among all words, one that is inauthentic, then surely it is the word “authentic.” Maurice Blanchot1 Welcome to the future of Los Angeles. It is a city made up entirely of brands, logos, and trademarked characters. Every visual landmark in the city has been stamped with a brand. Every resident is a branded or licensed charac- ter: Ronald MacDonald wreaks havoc on the city, the cops are the rounded, treaded lumps of the Michelin tire logo, crowds of people are depicted as the America On-Line instant message logo, Bob’s Big Boy is taken hostage and finds a love match in the Esso girl. Anonymous individuals walk around the city with the trademark symbol ™ hovering about their heads. Scanning the skyline, we see the U-Haul building, the Eveready skyscraper, the MTV apartment building. Corporate logos—Microsoft, BP, Enron, Visa, and countless others— blanket the city’s infrastructure, including the roads, cars, and even the city zoo. The animals in the zoo are also brands: the lion of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer film corporation, the alligator from Lacoste clothing company, and Microsoft Window’s butterflies, with the zoo tour bus driven by the iconic Mr. Clean. || 1 9780814787137 _banetWeiser_text.idd 1 8/8/12 10:46 AM 2 || BRANDING THE AUTHENTIC Logorama’s brand landscape. Ronald McDonald holding Bob’s Big Boy hostage. This is the world of Logorama, a sixteen-minute animated short film writ- ten and directed in 2009 by the French creative collective H5, composed of François Alaux, Hervé de Crécy, and Ludovic Houplain.2 The film’s simple and familiar narrative—which replicates an age-old trope of good versus evil—takes place in a futuristic, stylized, war-zone Los Angeles, where a homicidal psychopath armed with a gun takes people hostage, wreaks havoc on the city, and leads the police in a prolonged, violent chase.