Engaging with Advertising Media in a Constructivist Classroom: Case Study of a Rural Seventh Grade Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Sessões Recomendadas Para Crianças L São, Além Das INFANTIS: FUTURO ANIMADOR E ANIMATV

PETROBRAS apresenta k'FTUJWBM*OUFSOBDJPOBM EF"OJNB}{PEP#SBTJM 3JPEF+BOFJSP BEF+VMIP Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil Centro Cultural Correios Casa França-Brasil Oi Futuro Cinema Odeon-BR Unibanco Arteplex Botafogo 4P1BVMP EF+VMIPBnEF"HPTUP Memorial da América Latina Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil 1 ATENÇÃO: Anima Mundi informa que as sessões recomendadas para crianças L são, além das INFANTIS: FUTURO ANIMADOR e ANIMATV. 14 As demais sessões não são recomendadas para menores de 14 anos. RIO DE JANEIRO Locais De Exibição Obs: Pagam meia-entrada: maiores de 60 (sessenta) anos e crianças até 12 (doze) anos. Centro Cultural Casa França-Brasil Banco do Brasil (CCBB) Rua Visconde de Itaboraí, 78, Centro Rua Primeiro de Março, 66, Centro Informações: (21) 2332-5121 Informações: (21) 3808-2020 Horário de funcionamento: Horário de funcionamento: 10h às 21h Estúdio Aberto: Ter a Dom 13h às 19h, Ingresso: R$ 6,00 (meia entrada R$ 3,00) Entrada franca Sessões gratuitas: Infantis, AnimaTV e Futuro Animador, retirada de senhas somente no dia da sessão Unibanco Arteplex Botafogo com 1 hora de antecedência na bilheteria Praia de Botafogo, 316 Térreo, Botafogo Informações: (21) 2559-8750 Centro Cultural Correios Horário de funcionamento: 12h às 22h Rua Visconde de Itaboraí, 20, Centro Ingresso: R$ 6,00 (meia entrada: R$ 3,00), Informações: (21) 2253-1580 Vendas por dia, a partir da abertura da bilheteria Horário de funcionamento: 11h30 às 19h30 Oi Futuro Flamengo · Sala de Cinema Rua Dois de Dezembro, 63, Flamengo Entrada Franca, Classificação Livre, Informações: -

Ca' Foscari Short Film Festival 7

Short ca’ foscari short film festival 7 1 15 - 18 MARZO 2017 AUDITORIUM SANTA MARGHERITA - VENEZIA INDICE CONTENTS × Michele Bugliesi Saluti del Rettore, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia × Michele Bugliesi Greetings from the Rector, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Flavio Gregori Saluti del Prorettore alle attività e rapporti culturali, × Flavio Gregori Greetings from the Vice Rector for Cultural activities and relationships, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Ca’ Foscari University of Venice × Board × Board × Ringraziamenti × Acknowledgements × Comitato Scientifico × Scientific Board × Giuria Internazionale × International Jury × Catherine Breillat × Catherine Breillat × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Małgorzata Zajączkowska × Barry Purves × Barry Purves × Giuria Levi Colonna Sonora × Levi Soundtrack Jury × Concorso Internazionale × International Competition × Concorso Istituti Superiori Veneto × Veneto High Schools’ Competition × Premi e menzioni speciali × Prizes and special awards × Programmi Speciali × Special programs × Concorso Music Video × Music Video Competition × Il mondo di Giorgio Carpinteri × The World of Giorgio Carpinteri × Desiderio in movimento - Tentazioni di celluloide × Desire on the move - Celluloid temptations × Film making all’Università Waseda × Film-making at Waseda University Waseda Students Waseda Students Il mondo di Hiroshi Takahashi The World of Hiroshi Takahashi × Workshop: Anymation × Workshop: Anymation × Il mondo di Iimen Masako × The World of Iimen Masako × C’era una volta… la Svizzera × Once upon a time… Switzerland -

Apocalyptic Desire and Our Urban Imagination

Apocalyptic DESIRE AND OUR URBAN Imagination AmY murphY University of Southern California INTRODUCTION The trouble with our times is that the future is not what it used to be. Paul Valery For approximately the last three millennia, some portion of the world’s population has subscribed to the notion that the world as we know it is going to be destroyed by the wrath of nature, the will of God, or by human development itself. While many apoca- lyptic references relate back to conservative religious traditions, a great number in circulation today are being promoted by progres- sive secular entities. Eco-theorist scholar Greg Garrard writes that not only has the notion of the apocalypse been present since the beginning of Judeo-Christian time, but the apocalyptic trope has more recently “provided the green movement with some if its most Figure 1. Opening shot of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988). striking successes,” in publications such as Rachel Carson’s Silent The apocalyptic trope has proven to be one of the most complic- Spring, Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb and Al Gore’s An In- it, resilient, and powerful metaphors used throughout our history convenient Truth.1 to manipulate human behavior. On one side, it continues to be a central rhetorical element connecting a multitude of conservative As demonstrated by Pixar’s Hollywood feature Wall-e or Hayao Mi- agendas (religious, military, and industrial) to justify an assumed yazaki’s popular anime film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, moral supremacy of one group over other humans as well as nature. -

Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled Tammy Mckillip Mckillip University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2016-01-01 Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled Tammy Mckillip Mckillip University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Mckillip, Tammy Mckillip, "Tumbling Dice and Other Tales from a Life Untitled" (2016). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 897. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/897 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED TAMMY MCKILLIP Master’s Program in Creative Writing APPROVED: ______________________________________ Liz Scheid, MFA, Chair ______________________________________ Lex Williford, MFA ______________________________________ Maryse Jayasuriya, Ph.D. _________________________________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED ©Tammy McKillip, 2016 This work is dedicated to my beautiful, eternally-young mother, who taught me how to roll. Always in a hurry, I never stop to worry, Don't you see the time flashin’ by? …You’ve got to roll me And call me the tumbling dice —The Rolling Stones TUMBLING DICE AND OTHER TALES FROM A LIFE UNTITLED BY TAMMY -

Catálogo De Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX

European and Latin American short film market Catálogo de Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX Bienvenidos / Welcome .................................................... 3 Programa Shortlatino / Shortlatino program ............. 5 PAÍSES EUROPEOS / EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PAÍSES LATINOS / LATIN COUNTRIES Alemania / Germany ........................................................ 11 Argentina / Argentina .................................................. 299 Austria / Austria .............................................................. 40 Brasil / Brazil .................................................................. 303 Bélgica / Belgium ............................................................. 41 Chile / Chile ................................................................... 309 Bulgaria / Bulgaria ......................................................... 49 Colombia / Colombia ...................................................... 311 Dinamarca / Denmark .................................................... 50 Costa Rica / Costa Rica ................................................ 315 Eslovenia / Slovenia ........................................................ 51 Cuba / Cuba ..................................................................... 316 España / Spain ................................................................. 52 México / Mexico ............................................................... 317 Estonia / Estonia ........................................................... 168 Perú / Peru .................................................................... -

Tidligere Vindere 1975-2012

I dette dokument kan du finde tidligere vindere af Odense Internationale Film Festival. Derudover kan du se, hvem der var jury det pågældende år samt læse en kort beskrivelse af de enkelte festivaler. Følg hyperlinksene herunder for at komme frem til det ønskede år: 1975, 1977, 1979, 1981, 1983, 1985, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012 Hvis du har spørgsmål, er du altid velkommen til at kontakte os på telefon 6551 2837 eller på mail [email protected] 1975, 27. juli – 4. august I 1975 afholdes festivalen for første gang under navnet Den Internationale Eventyrfestival. Festivalen kunne præsentere 58 udvalgte film fra 20 forskellige lande. Filmene blev vist i Palace Biografen. Juryen bestod af: - Jan Lenica, Polen - Thorbjørn Egner, Norge - Georg Poulsen, Danmark - Niels Oxenvad, Danmark - Ebbe Larsen, Danmark 1.pris - Guldpris THE THREE COMPANIONS af Jan Karpas, Tjekkoslovakiet THE LEGEND OF POUL BUNYAN af Sam Weiss, USA 2.pris - Sølvpris THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL af Kazuhiko Watanabe, Japan Vinderfilm THE FROG PRINCE af Jim Henson, USA THE SHADOW af Jørgen Vestergaard, Danmark THE SWINEHERD af Gene Deitch, Danmark ARROW TO THE SUN af Gerald McDermott, USA BLACK OR WHITE af Waclaw Wajser, Polen Personlige priser Thorbjørn Egner: THE BAG OF APPLES af Vladimir Bordzilovskij, U.S.S.R. Speciel Jurypris: THE SERIES OF CARTOONS af Raoul Servais, Belgien 1977, 31. juli - 7. august Den 2. Internationale Eventyrfestival bød på 68 film fra 18 forskellige lande. Filmene blev vist i Palads Teatret, Bio Centret, Folketeatret Grand og Bio Vollsmose. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

The Iafor Journal of Media, Communication & Film

the iafor journal of media, communication & film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Editor: James Rowlins ISSN: 2187-0667 The IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue – I IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Editor: James Rowlins, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Associate Editor: Celia Lam, University of Notre Dame Australia, Australia Assistant Editor: Anna Krivoruchko, Singapore University of Technology and Design, Singapore Advisory Editor: Jecheol Park, National University of Singapore, Singapore Published by The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Rachel Dyer IAFOR Publications. Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2016 ISSN: 2187-0667 Online: JOMCF.iafor.org Cover photograph: Harajuku, James Rowlins IAFOR Journal of Media, Communication & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Edited by James Rowlins Table of Contents Notes on Contributors 1 Introduction 3 Editor, James Rowlins Interview with Martin Wood: A Filmmaker’s Journey into Research 5 Questions by James Rowlins Theorizing Subjectivity and Community Through Film 15 Jakub Morawski Sinophone Queerness and Female Auteurship in Zero Chou’s Drifting Flowers 22 Zoran Lee Pecic On Using Machinima as “Found” in Animation Production 36 Jifeng Huang A Story in the Making: Storytelling in the Digital Marketing of 53 Independent Films Nico Meissner Film Festivals and Cinematic Events Bridging the Gap between the Individual 63 and the Community: Cinema and Social Function in Conflict Resolution Elisa Costa Villaverde Semiotic Approach to Media Language 77 Michael Ejstrup and Bjarne le Fevre Jakobsen Revitalising Indigenous Resistance and Dissent through Online Media 90 Elizabeth Burrows IAFOR Journal of Media, Communicaion & Film Volume 3 – Issue 1 – Spring 2016 Notes on Contributors Dr. -

Download Program

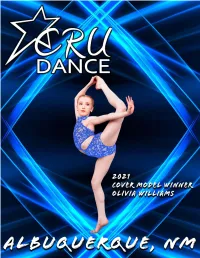

Tun fo e vi r yo IN rtua ur l aw ards Friday 7pm est on our facebook page @crudance competition convention live stream scholarships cash awards 3 competitive level entertainment winner choreographer winner and much more! CRU DANCE Saturday May 1st - Sunday May 2nd, 2021 ALBUQUERQUE, NM KIVA AUDITORIUM Saturday May 1st, 2021 Start Time: 9:00am Studio Check in- Studio A, F, P 8:30 AM Violet Bleger, Jolie Chowen, Sydney 1 P Waltz from Giselle Teen Pointe Small Group Intermediate DeLacey, Hannah Dobesh, Diana 9:00 AM Koshevoy, Sutton Schreiber, Anna Wiley 2 A Maniac Mini Acrobat Solo Intermediate Maria Moreno 9:03 AM Shaylah Apodaca, Zanae Cadena, Nadia Erives, Maria Gamez, Arianna Guzman, 3 F Grown Junior Jazz Small Group Novice 9:05 AM Jadelyne Maldonado, Alyson Ortiz, Nevaeh Ramos Gabriella Albert, Blythe Bleger, Maya Fontenot, Abigail Grindstaff, Rose Hamill, 4 P Don Quixote Ensemble Junior Ballet Large Group Novice 9:08 AM Gillian Reynolds, Eden Smith, Grace Tranum, Sophia Valdez, Naomi Verow 5 P Paquita Variation Senior Pointe Solo Elite Anna Wiley 9:12 AM 6 P Odalisque Variation Teen Pointe Solo Intermediate Hannah Dobesh 9:15 AM Alecia Baca, Bianca Gandara, Sonrisa Gonzales Atencio, Camilla Meraz, Ana 7 F Castle Teen Contemporary Large Group Novice 9:18 AM Oropeza, Carisse Padilla, Elicia Peralta, Jackie Pinon, Joslyn Purcella, Natalie Veleta Variation From Don 8 P Senior Pointe Solo Elite Sydney DeLacey 9:22 AM Quixote 9 P Perfect Senior Contemporary Solo Elite Anna Wiley 9:25 AM 10 P La Fille Mal Gardee Senior Pointe Duets/Trios -

Courts-Metrages

COURTS-METRAGES vieux dessins animés libres de droits (Popeye, Tom et Jerry, Superman…) : https://archive.org/details/animationandcartoons page d’accueil (adultes et enfants (films libres de droit) : https://www.apar.tv/cinema/700-films-rares-et-gratuits-disponibles-ici-et-maintenant/ page d’accueil : https://films-pour-enfants.com/tous-les-films-pour-enfants.html page d’accueil : https://creapills.com/courts-metrages-animation-compilation-20200322 SELECTION Un film pour les passionnés de cyclisme et les nostalgiques des premiers Tours de France. L'histoire n'est pas sans rappeler la réelle mésaventure du coureur cycliste français Eugène Christophe pendant la descente du col du Tourmalet du Tour de France 1913. Eugène Christophe cassa la fourche de son vélo et marcha 14 kilomètres avant de trouver une forge pour effectuer seul la réparation, comme l'imposait le règlement du Tour. Les longues moustaches du héros sont aussi à l'image d'Eugène Christophe, surnommé "le Vieux Gaulois". (7minutes , comique) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/14.html pickpocket Une course-poursuite rocambolesque. (1minute 27) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/korobushka.html salles gosses (1 minutes 30) Oui, les rapaces sont des oiseaux prédateurs et carnivores ! Un film comique et un dénouement surprenant pour expliquer aux enfants l'expression "être à bout de nerfs". https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/sales-gosses.html i am dyslexic (6 minutes 20) Une montagne de livres ! Une très belle métaphore de la dyslexie et des difficultés que doivent surmonter les enfants dyslexiques. https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/i-am-dyslexic.html d'une rare crudité et si les plantes avaient des sentiments (7 minutes 45) Un film étrange et poétique, et si les plantes avaient des sentiments. -

The Riverdale Park

The Riverdale Park Town Crier September 2021 Volume 50, Issue 7 SPECIAL ELECTION NOTICE Ward 1 Special Election Page 1 Council Actions Page 2 AVISO DE ELECCIÓN ESPECIAL Fair Summaries Page 3 Ward 1 Special Election Page 3 In compliance with the terms of the Charter of the Mayor’s Report Page 4 Town Extensions Page 5 Town of Riverdale Park, Maryland, a Special Election will be held Stay-Up-To-Date Page 5 Virtual Meetings Page 6 Conforme a los Estatutos de la Ciudad de Riverdale Park, 2021 Dates Page 6 Mosquito Control Page 7 Maryland, se celebrará una elección el Neighborhood Services Page 8 Emergency Repair Grant Page 8 Saturday, September 11, 2021 Covid-19 Vaccine Page 9 Notices Page 9 - 10 To elect a Ward 1 Council Member Calendar Page 11 Important Numbers Page 12 Sábado, 11 de septiembre de 2021 Para elegir al Consejo del Distrito 1 Polls will be open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. at Riverdale Fire Department, 4714 Queensbury Road Town of Riverdale Park Contact Information Las urnas abrirán de 7 a.m. a 8 p.m. en el Departamento de Bomberos de Riverdale, Town Hall 4714 Queensbury Road 5008 Queensbury Road 301-927-6381 CANDIDATES 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. CANDIDATOS Department of Public Works Council, Ward 1 5008 Queensbury Road Consejo, Distrito 1 301-927-6381 IFIOK INYANG 7:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Police Department RICHARD SMITH 5004 Queensbury Road 301-927-4343 Sarah Zolad, Chief Election Judge 24-hours Anne Kelly, Deputy Chief Election Judge Town of Riverdale Park Council Actions www.riverdaleparkmd.gov Cable Channels: 10 and 71 Legislative Meeting July 12, 2021 Mayor Consent Agenda Alan K.