Does AACHEN Provide the Missing Urban Splendor for the Early Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideazione Di Clementina Panella a Cura Di Alessandro D'alessio

Ideazione di Clementina Panella A cura di Alessandro D’Alessio Clementina Panella Rossella Rea ROMA UNIVERSALIS SEZIONE I SEZIONE II 206 Tombe e necropoli a Roma SEZIONE III L’IMPERO E LA DINASTIA L’IMPERO DEI SEVERI LA ROMA DEI SEVERI e dintorni ROMA E IL MEDITERRANEO VENUTA DALL’AFRICA Barbara E. Borg LA DINASTIA LA FORMA DELLA CITTÀ 210 Linguaggio architettonico e sistemi CITTÀ, TERRITORI, ECONOMIE 23 I Severi e i caratteri di un’epoca. 36 I Severi 132 Urbs Roma – Urbs Sacra: forma decorativi dei grandi complessi 264 La Sicilia Continuità e frattura nella storia Orietta D. Cordovana e immagini della Città di Roma Daniele Malfitana della popolazione di Roma Domenico Palombi L’IMPERO IN PACE Patrizio Pensabene, Francesca Caprioli 270 L’Africa e del suo impero mediterraneo 48 Moneta, economia e cittadinanza I LUOGHI SEVERIANI Alejandro Quevedo Elio Lo Cascio 220 L’industria laterizia e Marco Maiuro 142 Le “Terme di Elagabalo” l’organizzazione dei grandi 278 L’Egitto 28 Cronologia dell’età severiana. Clementina Panella 58 Società, cultura, religione cantieri urbani Jessica Montani 192-235 Cesare Letta 150 I reperti scultorei dalle Évelyne Bukowiecki, 282 Dal Mediterraneo a Roma “Terme di Elagabalo”: dall’età Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt † L’IMPERO IN GUERRA Clementina Panella augustea all’età severiana 64 Gli eserciti: riforme, campagne Massimiliano Papini L’IMPERATORE E LA PLEBE URBANA militari e nuove province 228 Intrattenere e sorprendere: ludi, 298 Abbreviazioni Cecilia Ricci 154 Il Tempio di Elagabalo munera e agones Françoise Villedieu 300 Bibliografia ARTE E ARCHITETTURA Silvia Evangelisti 72 Luoghi, monumenti, immagini: 158 La Domus Severiana sul Palatino. -

Foro Romano E Palatino

Foro Romano e Palatino Visite guidate Bookshop La valle del Foro tra i sette colli di Roma era anticamente una palude. Dalla fine del VII secolo a.C. dopo la bonifica della palude nella valle fu realizzato il Foro Romano che fu il centro della vita pubblica romana per oltre un millennio. Nel corso dei secoli furono costruiti i vari monumenti: dapprima gli edifici per le attività politiche, religiose e commerciali, poi durante il II sec. a.C. le basiliche civili, dove si svolgevano le attività giudiziarie. Alla fine dell’età repubblicana, l’antico Foro Romano era ormai insufficiente e inadeguato a svolgere la funzione di centro amministrativo e di rappresentanza della città. Le varie dinastie di imperatori aggiunsero solo monumenti di prestigio: il Tempio di Vespasiano e Tito e quello di Antonino Pio e Faustina dedicati alla memoria degli imperatori divinizzati, il monumentale Panorama del Foro Romano Arco di Settimio Severo, costruito all’estremità occidentale della piazza nel 203 d.C. per celebrare le vittorie dell’imperatore sui Parti. L’ultimo grande intervento fu realizzato dall’imperatore Massenzio ai primi anni del IV secolo d.C. Massenzio fece costruire il Tempio dedicato alla memoria del figlio Romolo e l’imponente Basilica sulla Velia che fu ristrutturata alla fine del IV secolo d.C. L’ultimo monumento realizzato nel Foro fu la Colonna eretta nel 608 d.C. in onore dell’imperatore bizantino Foca. Luogo | Indirizzo Indirizzo: Via di San Gregorio 30 e Largo della Salara Vecchia 5/6 Cap: 00184 Comune: Roma Provincia: Roma (RM) Regione: Lazio Telefono: 06699841 0639967700 Fax: 066787689 Sito web: http://www.archeoroma.beniculturali.it/sar2000/palatino/palatino.htm Luogo | Galleria delle Immagini Panorama del Foro Veduta della Basilica Casa delle Vestali, Casa delle Vestali Via Nova Tempio di Venere Romano Emilia veduta ADArte | Sintesi di accessibilità Informazioni raccolte con un sopralluogo terminato il 12 ottobre 2012. -

Thinking Big. Research in Monumental Constructions in Antiquity

Special Volume 6 (2016): Space and Knowledge. Topoi Research Group Articles, ed. by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, pp. 250–305. Hagan Brunke – Evelyne Bukowiecki – Eva Cancik- Kirschbaum – Ricardo Eichmann – Margarete van Ess – Anton Gass – Martin Gussone – Sebastian Hageneuer – Svend Hansen – Werner Kogge – Jens May – Hermann Parzinger – Olof Pedersén – Dorothée Sack – Franz Schopper – Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt – Hauke Ziemssen Thinking Big. Research in Monumental Constructions in Antiquity Edited by Gerd Graßhoff and Michael Meyer, Excellence Cluster Topoi, Berlin eTopoi ISSN 2192-2608 http://journal.topoi.org Except where otherwise noted, content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 Hagan Brunke – Evelyne Bukowiecki – Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum – Ricardo Eichmann – Margarete van Ess – Anton Gass – Martin Gus- sone – Sebastian Hageneuer – Svend Hansen – Werner Kogge – Jens May – Hermann Parzinger – Olof Pedersén – Dorothée Sack – Franz Schopper – Ulrike Wulf-Rheidt – Hauke Ziemssen Thinking Big. Research in Monumental Constructions in Antiquity Ancient civilizations have passed down to us a vast range of monumental structures. Mon- umentality is a complex phenomenon that we address here as ‘XXL’.It encompasses a large range of different aspects, such as sophisticated technical and logistical skills and the vast economic resources required. This contribution takes a closer look at the special interdependence of space and knowledge represented by such XXL projects. We develop a set of objective criteria for determining whether an object qualifies as ‘XXL’,in order to permit a broadly framed study comparing manifestations of the XXL phenomenon in different cultures and describing the functional and conceptional role of the phenomenon in antiquity.Finally,we illustrate how these criteria are being applied in the study of large construction projects in ancient civilisations through six case studies. -

(Michelle-Erhardts-Imac's Conflicted Copy 2014-06-24).Pages

ROME MMXV Piety, Pagans and Popes CLST 370: Seminar Abroad in Rome 2015 From its foundation through its expansion as an empire, to the rise of the papacy, Rome has served as a showcase of political and religious power through art, architecture and urban form. This course will examine the Eternal City’s most significant architectural and urban sites, moving roughly in chronological order. We will discuss how individual monuments assume symbolic importance, how they serve as models of architectural style, and how the sites take on a “sacred” quality both inside and outside of a religious context. This course is intended to offer students an introduction to the city of Rome that is architectural, artistic, and topographic in nature. Excursions to Etruscan tombs, Assisi and Florence help put Rome in a larger cultural context. " Tentative Itinerary" Friday, May 29th! Arrival in Rome Benvenuto a Roma! Check into the Centro - Piazzale del Gianicolo (view of Rome) -A walk through Trastevere: Sta. Cecilia, church and underground domus; S. Francesco a Ripa; Sta. Maria; S. Pietro in Montorio (Bramante’s Tempietto)." Saturday, May 30th! Cerveteri - Tarquinia Etruscan Influences on Early Rome. Half-Day Trip to Cerveteri or Tarquinia followed by afternoon visit to the Villa " Giulia (Etruscan Museum). ! Sunday, May 31st! Circus Flaminius Foundations of Early Rome, Military Conquest and Urban Development. Isola Tiberina (cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius) - Santa Maria in Cosmedin: Ara Maxima Herculis - Forum Boarium: Temple of Hercules Victor and Temple of Portunus - San Omobono: Temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta - San Nicola in Carcere - Triumphal Way Arcades, Temple of Apollo Sosianus, Porticus Octaviae, Theatre of Marcellus. -

Severan Culture Edited by Simon Swain, Stephen Harrison and Jas´ Elsner Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85982-0 - Severan culture Edited by Simon Swain, Stephen Harrison and Jas´ Elsner Frontmatter More information Severan culture The Roman empire during the reigns of Septimius Severus and his successors (ad 193–225) enjoyed a remarkably rich and dynamic cul- tural life. It saw the consolidation of the movement known as the Second Sophistic, which had flourished during the second century and promoted the investigation and reassessment of classical Greek culture. It also witnessed the emergence of Christianity on its own terms, in Greek and in Latin, as a major force extending its influ- ence across literature, philosophy, theology, art and even architecture. This volume offers the first wide-ranging and authoritative survey of the culture of this fascinating period when the background of Rome’s rulers was for the first time non-Italian. Leading scholars discuss gen- eral trends and specific instances, together producing a vibrant picture of an extraordinary period of cultural innovation rooted in ancient tradition. simon swain is Professor of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. His recent publications include Bilingualism in Ancient Society (2002) (with J. N. Adams and M. Janse), Approaching Late Antiquity (2004) (with M. Edwards) and Seeing the Face, Seeing the Soul: Polemon’s Physiognomy from Classical Antiquity to Medieval Islam (2007). stephen harrison is Professor of Classical Languages and Lit- erature at the University of Oxford and Fellow and Tutor in Classics at Corpus Christi College. His numerous publications include A Com- mentary on Vergil, Aeneid 10 (1991), Apuleius: A Latin Sophist (2000), Generic Enrichment in Vergil and Horace (2007) and, as editor, The Cambridge Companion to Horace (2007). -

The House of the Rising Sun: Luminosity and Sacrality from Domus to Ecclesia

Fabio Barry The House of the Rising Sun: Luminosity and Sacrality from Domus to Ecclesia The poem In praise of the younger Justin (566/567 AD) was the last flowering of Latin panegyricepic in Byzantium, written by Corippus, court poet to Justin II (r. 565578). In one passage, the poet offers this ekphrasis of the Emperor’s throneroom in the recently completed Sophia Palace: There is a hall within the upper part of the palace That shines with its own light as though it were open to the clear sky And so gleams with the intense luster of glassy minerals, That, if one may say so, it has no need of the golden sun And it ought really be named the ‘Abode of the Sun’ So pleasing is the sight of the place and still more wondrous in appea- rance1. One commentator has taken these words at face value to mean “a kind of solarium, with walls and perhaps roof of glass.”2 Instead, the poet means a chamber sheathed in glass mosa- ic (“vitrei… metalli”), indubitably vaulted not glazed, and abounding in such gleaming reflec- tions that the room seemed to illuminate itself. It was a throneroom worthy of the Sun himself and the emperor Justin, we are to understand, is that Sun. This interpretation is more than confirmed by the permutations on the theme that pervade the rest of the poem: Justin acce- ded to the throne at dawn and light filled the palace at his acclamation; his father Justinian (fig. 1) was “the light of the city and the world”; Justin’s royal limbs emit light; the “imperial palace with its officials is like Olympus. -

Roman Art 12.1

THE SEVERANS • Marcus Aurelius = last of the “5 good emperors” • son Commodus deranged -megalomania -divine aspirations (Hercules and Jupiter) -no interest in statecraft or military -renamed himself “Hercules Romanus” -renamed Rome “Colonia Commodiana” • portraiture highly resembles father -beard, heavy eyelids, aloof gaze • assassinated with damnatio memoriae in 192 -later rescinded à Marcus Aurelius, d. 180 CE Commodus THE SEVERANS IN ROME Five Good Emperors (96-180) à Commodus (180-192) à Civil War à SEVERANS • Septimius Severus born in N. Africa (Leptis Magna, Libya) • assumes imperial throne in 193 CE after successful military career • two sons, Caracalla and Geta à à Caracalla (198-217) Commodus Septimus Severus (193-211) Geta (killed in 212) Forma Urbis Romae • Severan map of entire city • installed in Te m plu m Pacis • shows all buildings, streets, infrastructure, building heights • most important monuments labelled • function unknown http://formaurbis.stanford.edu Severan Palace (domus Severiana) on the Palatine • only substructures survive • included private bath complex • looms over Circus Maximus Septizodium • monumental structure attested in literary evidence • destroyed in late 16th c. • partially documented and labeled on Forma Urbis plan • elevation recorded in multiple drawings prior to destruction • 3 storeys of columns -resembles stages of Roman theatres Function of Septizodium • monumental fountain • visual anchor for those entering city from S “Septizodium” • name only attested for monuments in N. Africa • general -

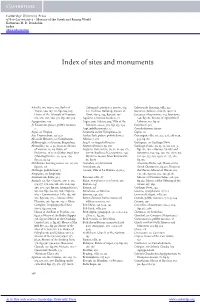

Index of Sites and Monuments

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-00230-1 - Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World Katherine M. D. Dunbabin Index More information Index of sites and monuments Acholla, 103, 104–5, 295; Baths of Colonnade, porticoes, 179–80, 304 Cabezón de Pisuerga, villa, 322 Trajan, 104, 107, 111, figs.104, 105; n.3; Triclinos Building, mosaic of Caesarea (Judaea), church, 196 n.19 House of the Triumph of Neptune, Hunt, 183–4, 234, figs.196, 197 Caesarea (Mauretania), 124; fountains, 105, 106, 280, 288, 310, figs.106, 309 Aquileia, Christian basilicas, 71 246, fig.261; Mosaic of Agricultural Agrigentum, 130 Argos, 299; Odeion, 304; Villa of the Labours, 117, fig.121 Ai Khanoum, palace, pebble mosaics, Falconer, 220–2, 305, figs.233, 234 Caminreal, 318 17 Arpi, pebble mosaics, 17 Camulodunum, 89–90 Aigai, see Vergina Arsameia on the Nymphaios, 30 Capsa, 117 Ain-Témouchent, 323 n.31 Arslan Tash, palace, pebble floor, 5 Carranque, villa, 155, 272, 276, 286 n.29, Alcalá de Henares, see Complutum Athens, 7, 271 323, fig.162 Aldborough, see Isurium Brigantum Augst, see Augusta Raurica Cartagena, see Carthago Nova Alexandria, 22–4, 32, 274 n.25; Mosaic Augusta Raurica, 79, 280 Carthage, Punic, 20, 33, 53, 101, 102–3, of warrior, 23, 24; Palace of Augusta Treverorum, 79, 81, 82, 94, 271, figs.101, 102; – Roman, Vandal and Ptolemies, 26 n.25; Shatby, Stag Hunt 317–18; Basilica of Constantine, 246; Byzantine, 103, 104, 107, 125, 127 n. 66, (Hunting Erotes), 20, 23–4, 254, Mysteries mosaic from Kornmarkt, 128, 130, 137, 138, 139 n.21, 257, 280, figs.22, 23, 24 82, fig.85 -

Aqueducts for the Urbis Clarissimus Locus: the Palatine’S Water Supply from Republican to Imperial Times

AQUEDUCTS FOR THE URBIS CLARISSIMUS LOCUS: THE PALATINE’S WATER SUPPLY FROM REPUBLICAN TO IMPERIAL TIMES Dr. Andrea Schmölder-Veit, University of Augsburg [email protected] The Palatine hill, where Rome began, was already an to the Palatine’s water supply occurred under Nero, who important center of power long before Imperial palaces built the first unified palace building (not a collection of were built there. As early as the Republican period, elite several independent domus as Augustus had done).7 For residents had constructed monumental architecture on this this he needed more water; therefore, he sponsored a hill above the Roman Forum that publicly advertised their completely new branch that extended the Arcus Neroniani claims to leadership. Also at this time, the greatness of the (Arcus Caelimontani) on the Caelian to the Palatine. This res publica was demonstrated through monumental higher-level line could deliver water to every level of the building projects, which correlated with the gloria of hill, even to nymphaea in the highest courts and gardens. families who dedicated temples in Rome's honor.1 As nothing is known about the domus of this period, it can The first conduit for the Palatine in Republican times only be assumed that the Palatine was a residential area The Marcia was the only aqueduct to supply the Palatine populated by elite Romans in the fourth and third century hill during the Republican period. The Aqua Appia (312 BC. For example, Livy (8: 19. 4) tells us that Vitruvius BC) arrived at only about 15 masl (meters above sea level) Vaccus, a very rich Fundanian, had a property on the in the city.8 This was too low, even for the houses at the Palatine before 330 BC. -

Byzantine Mosaics in Istanbul in Nineteenth-Century French Guide-Books Korpus Öncesi: 19

JMR 8, 2015 81-100 Before the Corpus: Byzantine Mosaics in Istanbul in Nineteenth-Century French Guide-Books Korpus Öncesi: 19. Yüzyıl Fransız Rehber Kitaplarında İstanbul Bizans Mozaikleri Helene MoRlieR* (Received 16 March 2015, accepted after revision 11 November 2015) Abstract The study of a series of nineteenth-century French guide-books shows the evolution of the art of travel: guide- books were first based on the experience of travellers and the documentation summarized by writers. Little by little, guide-books became more detailed and gave more accurate descriptions of the ornamentation of build- ings: art history replaced general impressions. Guide-books also witnessed the changes of mentalities on both sides: foreign visitors and local citizens. Keywords: Istanbul, guide-books, nineteenth-century travel, Byzantine church, art history. Öz 19. yüzyıla ait bir dizi Fransız rehber kitapları çalışması, seyahat sanatının gelişimini göstermektedir. Rehber kitaplar ilk olarak, seyyahların deneyimlerine ve yazarlarca özetlenen belgelere dayanmaktadır. Zaman geç- tikçe rehber kitaplar daha detaylı olmuş ve yapıların süslemeleri hakkında daha doğru tanımlamalar vermiştir: Sanat tarihi, genel izlenimlerin yerini almıştır. Rehber kitaplar aynı zamanda her iki tarafta yani yabancı zi- yaretçiler ve yerli vatandaşlar arasında zihniyet değişimlerine de tanık olmuştur Anahtar Kelimeler: İstanbul, rehber kitaplar, 19. yüzyıl seyahati, Bizans kilisesi, sanat tarihi. How did nineteenth-century guide-books pay attention to mosaics? What was written about them? How were they considered? The table (Fig. 1) recapitulates the publications of the main series of guide-books published during the nineteenth-century in the three main european languages used by travellers (French, english and German). As guide-books are too numerous to be studied comprehensively in this paper, i will focus on a forgotten series of guide-books published in French from the end of the eighteenth century up to the end of the First World War which included the Joanne guide-books. -

On Wall Decorations in Sectile Work As Used by the Romans, Icith Special Reference to the Decorations of the Palace of the Bassi at Borne

X.— On Wall Decorations in Sectile Work as used by the Romans, icith special reference to the Decorations of the Palace of the Bassi at Borne. By ALEXANDER NESBITT, Esq., F.iS.A. Bead November 24th, 1870. IT is proposed in the following memoir to do two things : one, to give some account of that species of mosaic decoration which by the Romans was dis- tinguished as " opus sectile," particularly as applied on walls; the other, to describe the very remarkable building which has afforded by far the most important examples of work of that character of which we have any knowledge, viz., the church of San Andrea in Catabarbara, which was probably originally the great hall or basilica of the palace of the Bassi on the Esqailine hill in Rome. Those collocations of pieces of stone, glass, or baked clay which we are accus- tomed to call mosaics may be divided into three classes; first, that in which fragments of stone or glass without any definite shape are fixed in cement and polished down to a smooth surface; second, that in which the pieces are all small cubes; and third, that in which the materials employed are in slices, and are so cut into shapes, geometrical or other, that when put together they form a pattern. The first kind is still in use in Italy, where it is known as "alia Veneziana." A good ancient example exists in the " House of the Eaun " at Pompeii; this contains many pieces of transparent amethystine and opaque crimson glass. The second kind, called " tessellatum," as being composed of tessellse, is too well known to need any description. -

Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World

MOSAICS OF THE GREEK AND ROMAN WORLD KATHERINE M. D. DUNBABIN The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge , United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, , UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk West th Street, New York, –, USA http://www.cup.org Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © Cambridge University Press This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in / ⁄pt Minion in QuarkXPress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World / Katherine M. D. Dunbabin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. x hardback . Mosaics, Ancient. I. Title. .Ј–dc – hardback Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association Contents List of plates viii PART I: Historical and regional development List of figures x List of maps xx . Origins and pebble mosaics . The invention of tessellated mosaics: Preface xxi Hellenistic mosaics in the east Introduction . Hellenistic mosaics in Italy . Mosaics in Italy: Republican and Imperial . The north-western provinces . Britain . The North African provinces . Sicily under the Empire: Piazza Armerina . The Iberian peninsula . Syria and the east . Palestine and Transjordan . Greece: the Imperial period . Asia Minor, Cyprus, Constantinople . Wall and vault mosaics . Opus sectile PART II: Technique and production .