Pointing Our Thoughts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foreign Service Journal, January 1951

gL AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL JANUARY, 1951 .. .it’s always a measure warn ,0? KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOUHBOI WHISKEY W/A BOTTLED IN BOND KENTUCKY BOURBON KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY • TOO PROOF • I. W. HARPER DISTILLING COMPANY, KENTUCKY REGISTERED DISTILLERY NO. 1, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION HONORARY PRESIDENT FOREIGN SERVICE DEAN ACHESON SECRETARY OF STATE HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS THE UNDER SECRETARY OF STATE THE ASSISTANT SECRETARIES OF JOURNAL STATE THE COUNSELOR H. FREEMAN MATTHEWS PRESIDENT FLETCHER WARREN VICE PRESIDENT BARBARA P. CHALMERS EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE HERVE J. L.HEUREUX CHAIRMAN HOMER M. BYINGTON, JR. VICE CHAIRMAN WILLIAM O. BOSWELL SECRETARY-TREASURER DALLAS M. COORS ASSISTANT SECRETARY-TREASURER CECIL B. LYON ALTERNATES THOMAS C. MANN EILEEN R. DONOVAN STUART W. ROCKWELL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY U. ALEXIS JOHNSON ANCEL N. TAYLOR THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION JOURNAL EDITORIAL BOARD JOHN M. ALLISON CHAIRMAN FRANK S. HOPKINS G. FREDERICK REINHARDT VOL, 28, NO. 1 JANUARY, 1951 WILLIAM J. HANDLEY CORNELIUS J. DWYER JOHN K. EMM FRSON AVERY F. PETERSON COVER PICTURE: A snowstorm blankets old Jerusalem. DAVID H. MCKILLOP Photo by FSO William C. Burdett, Jr. JOAN DAViD MANAGING EDITOR ROBERT M. WINFREE REGIONAL CONFERENCES IN 1950 13 ADVERTISING MANAGER By Alfred H. Lovell, FSO EDUCATION COMMITTEE REGIONAL CONFERENCE AT THE HAGUE 16 G. LEWIS JONES CHAIRMAN By Thomas S. Estes, FSO H. GARDNER AINSWORTH MRS. JOHN K. EMMERSON MRS. ARTHUR B. EMMONS III WHAT! NO SPECIALISTS? 18 JOSEPH N. GREENE. JR. By Thomas A. Goldman, FSO J. GRAHAM PARSONS MRS. JACK D. NEAL THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE FORMER ITALIAN COLONIES 2C ENTERTAINMENT COMMITTEE By David W. -

A Nation at Risk

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform A Report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education United States Department of Education by The National Commission on Excellence in Education April 1983 April 26, 1983 Honorable T. H. Bell Secretary of Education U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202 Dear Mr. Secretary: On August 26, 1981, you created the National Commission on Excellence in Education and directed it to present a report on the quality of education in America to you and to the American people by April of 1983. It has been my privilege to chair this endeavor and on behalf of the members of the Commission it is my pleasure to transmit this report, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. Our purpose has been to help define the problems afflicting American education and to provide solutions, not search for scapegoats. We addressed the main issues as we saw them, but have not attempted to treat the subordinate matters in any detail. We were forthright in our discussions and have been candid in our report regarding both the strengths and weaknesses of American education. The Commission deeply believes that the problems we have discerned in American education can be both understood and corrected if the people of our country, together with those who have public responsibility in the matter, care enough and are courageous enough to do what is required. Each member of the Commission appreciates your leadership in having asked this diverse group of persons to examine one of the central issues which will define our Nation's future. -

CRISIS of PURPOSE in the IVY LEAGUE the Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education

Institutions in Crisis CRISIS OF PURPOSE IN THE IVY LEAGUE The Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education Rebecca Dunning and Anne Sarah Meyers In 2001, Lawrence Summers became the 27th president of Harvard Univer- sity. Five tumultuous years later, he would resign. The popular narrative of Summers’ troubled tenure suggests that a series of verbal indiscretions created a loss of confidence in his leadership, first among faculty, then students, alumni, and finally Harvard’s trustee bodies. From his contentious meeting with the faculty of the African and African American Studies Department shortly af- ter he took office in the summer of 2001, to his widely publicized remarks on the possibility of innate gender differences in mathematical and scientific aptitude, Summers’ reign was marked by a serious of verbal gaffes regularly reported in The Harvard Crimson, The Boston Globe, and The New York Times. The resignation of Lawrence Summers and the sense of crisis at Harvard may have been less about individual personality traits, however, and more about the context in which Summers served. Contestation in the areas of university governance, accountability, and institutional purpose conditioned the context within which Summers’ presidency occurred, influencing his appointment as Harvard’s 27th president, his tumultuous tenure, and his eventual departure. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution - Noncommercial - No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You may reproduce this work for non-commercial use if you use the entire document and attribute the source: The Kenan Institute for Ethics at Duke University. -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

Mailed free to requesting homes in Thompson Vol. VII, No. 32 Complimentary to homes by request (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] FRIDAY, MAY 4, 2012 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE Committee to search for grants to fund mill clean up SELECTMEN HOPEFUL PROPERTY MAY SEE NEW LIFE AS PARK “Self-development BY KERENSA KONESNI ble left behind after a series expressed by what is now the – as is the case with the is a higher duty VILLAGER STAFF WRITER of owners removed the valu- Department of Energy and Belding site, the corporation THOMPSON — After clean able portions of its construc- Environmental Protection that retains responsibility than self-sacrifice.” up efforts were derailed by tion, leaving piles of bricks (DEEP) drew the process out, for the clean up and remedia- the downturn in the econo- and concrete behind a chain and with trucks on the tion of a site is often not pres- my, the site of the Belding- link fence near the heart of ground ready to begin clear- ent, if it exists at all. Corticelli Mill on Route 12 in the town. ing debris, the money to com- “The town is willing to find Thompson may be back on According to First plete the project privately ways to be creative but not to track to see clean up, remedi- Selectman Larry Groh, the ran out. According to Groh, take on the liability,” said ation and a change in the current owner of the site Scott owns the Belding- Kennedy. “So right now the INSIDE landscape. Andy Scott has said that he is Corticelli Mill free and clear. -

Citizen Culture Issue #6

corrections 11/22/05 11:17 AM Page 117 corrections 11/30/05 12:14 PM Page 3 38 106 75 TIDBITS JOURNALISM The Meth Mess Idiotic Inventive Crimes 8 Grace Carter 38 Mark Peters Must-Have Tech Gadgets 2005 8 Agha Khan TABLET: Fiction Recording in a Free World Phantom of Havana: 10 Paul Rouse 50 The Forgotten Legend of C.J. Fuentes El Rushbo, Gentle Arbiter Chris Wilson 12 Michael Serazio Flight 117, Tampa to Providence Insomnia Corner 55 Jennifer Farmer 15 Moisture Therapy Docents Against Darwin 59 Krista Jarmas 16 R.M Schneiderman ON THE FENCE TOCFrom the Left THE CCM INTERVIEW Sen. John McCain on 60 Dmitry Tuchinsky 18 Young Pros in 2006 65 From the Right Igor Finkel and Jonathon Scott Feit Ben Barron First Person SATIRE 70 Jill Dudones 21 A Good Day for John Bolton Seth Reiss 75 THE “F” WORD APHRODISIA CCM INVESTIGATES On Camping and Childbirth The NYC Security Paradox 23 Jen Karetnick 82 Team Coverage TRAVEL LOCAL FLAVOR: Anecdote Bluffed by Bali Adventures in Designer 26 Nicholas Gill 88 Handbag Shopping Amanda Joyce GLOBAL FOCUS Murder in Mongolia ARCHITECTURE 32 Claudia B. Flisi In Pursuit of Luxury issue92 Molly Klais #6 corrections 11/22/05 11:14 AM Page 4 124 102 92 MAGAZINES CONTRIBUTORS New York’s Arbiter of Cool JEN KARETNICK is a Miami-based freelance writer 99 Jonathon Scott Feit and poet. She works as the features editor for Wine 102 THE 6*4*6 News, the Miami stringer for Gayot.com and the restaurant critic for So.Florida Magazine, Las Olas LINES AND LISTS Magazine and Lincoln Road Magazine. -

Report Concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein's Connections to Harvard University

REPORT CONCERNING JEFFREY E. EPSTEIN’S CONNECTIONS TO HARVARD UNIVERSITY Diane E. Lopez, Harvard University Vice President and General Counsel Ara B. Gershengorn, Harvard University Attorney Martin F. Murphy, Foley Hoag LLP May 2020 1 INTRODUCTION On September 12, 2019, Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow issued a message to the Harvard Community concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein’s relationship with Harvard. That message condemned Epstein’s crimes as “utterly abhorrent . repulsive and reprehensible” and expressed “profound[] regret” about “Harvard’s past association with him.” President Bacow’s message announced that he had asked for a review of Epstein’s donations to Harvard. In that communication, President Bacow noted that a preliminary review indicated that Harvard did not accept gifts from Epstein after his 2008 conviction, and this report confirms that as a finding. Lastly, President Bacow also noted Epstein’s appointment as a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Psychology in 2005 and asked that the review address how that appointment had come about. Following up on President Bacow’s announcement, Vice President and General Counsel Diane E. Lopez engaged outside counsel, Martin F. Murphy of Foley Hoag, to work with the Office of General Counsel to conduct the review. Ms. Lopez also issued a message to the community provid- ing two ways for individuals to come forward with information or concerns about Epstein’s ties to Harvard: anonymously through Harvard’s compliance hotline and with attribution to an email ac- count established for that purpose. Since September, we have interviewed more than 40 individu- als, including senior leaders of the University, staff in Harvard’s Office of Alumni Affairs and Development, faculty members, and others. -

![1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, Nouveaux Regards » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2006, Consulté Le 13 Août 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3445/1895-mille-huit-cent-quatre-vingt-quinze-31-2000-%C2%AB-abel-gance-nouveaux-regards-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-06-mars-2006-consult%C3%A9-le-13-ao%C3%BBt-2020-563445.webp)

1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, Nouveaux Regards » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 06 Mars 2006, Consulté Le 13 Août 2020

1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 31 | 2000 Abel Gance, nouveaux regards Laurent Véray (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/1895/51 DOI : 10.4000/1895.51 ISBN : 978-2-8218-1038-9 ISSN : 1960-6176 Éditeur Association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma (AFRHC) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2000 ISBN : 2-913758-07-X ISSN : 0769-0959 Référence électronique Laurent Véray (dir.), 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze, 31 | 2000, « Abel Gance, nouveaux regards » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 06 mars 2006, consulté le 13 août 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/1895/51 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/1895.51 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 13 août 2020. © AFRHC 1 SOMMAIRE Approches transversales Mensonge romantique et vérité cinématographique Abel Gance et le « langage du silence » Christophe Gauthier Abel Gance, cinéaste à l’œuvre cicatricielle Laurent Véray Boîter avec toute l’humanité Ou la filmographie gancienne et son golem Sylvie Dallet Abel Gance, auteur et ses films alimentaires Roger Icart L’utopie gancienne Gérard Leblanc Etudes particulières Le celluloïd et le papier Les livres tirés des films d’Abel Gance Alain Carou Les grandes espérances Abel Gance, la Société des Nations et le cinéma européen à la fin des années vingt Dimitri Vezyroglou Abel Gance vu par huit cinéastes des années vingt Bernard Bastide La Polyvision, espoir oublié d’un cinéma nouveau Jean-Jacques Meusy Autour de Napoléon : l’emprunt russe Traduit du russe par Antoine Cattin Rachid Ianguirov Gance/Eisenstein, un imaginaire, un espace-temps Christian-Marc Bosséno et Myriam Tsikounas Transcrire pour composer : le Beethoven d’Abel Gance Philippe Roger Une certaine idée des grands hommes… Abel Gance et de Gaulle Bruno Bertheuil Étude sur une longue copie teintée de La Roue Roger Icart La troisième restauration de Napoléon Kevin Brownlow 1895. -

View Nomination

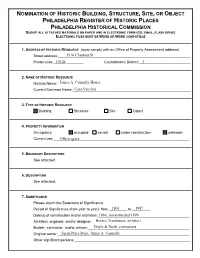

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

Classroom Design - Literature Review

Classroom Design - Literature Review PREPARED FOR THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON CLASSROOM DESIGN PROFESSOR MUNG CHIANG, CHAIR PRINCETON UNIVERSITY BY: LAWSON REED WULSIN JR. SUMMER 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In response to the Special Committee on spontaneous learning. So too does furnishing Classroom Design’s inquiry, this literature these spaces with flexible seating, tables for review has been prepared to address the individual study and group discussion, vertical question; “What are the current trends in surfaces for displaying student and faculty work, learning space design at Princeton University’s and a robust wireless network. peer institutions?” The report is organized into five chapters and includes an annotated Within the classroom walls, learning space bibliography. should be as flexible as possible, not only because different teachers and classes require The traditional transference model of different configurations, but because in order to education, in which a professor delivers fully engage in constructivist learning, students information to students, is no longer effective at need to transition between lecture, group preparing engaged 21st-century citizens. This study, presentation, discussion, and individual model is being replaced by constructivist work time. Furniture that facilitates rapid educational pedagogy that emphasizes the role reorganization of the classroom environment is students play in making connections and readily available from multiple product developing ideas, solutions, and questions. manufacturers. Already, teachers are creating active learning environments that place students in small work Wireless technology and portable laptop and groups to solve problems, create, and discover tablet devices bring the internet not just to together. every student’s dorm room, but also to every desk in the classroom. -

TWAS 27Th General Meeting - Kigali, Rwanda, 14-17 November 2016 List of Participants

TWAS 27th General Meeting - Kigali, Rwanda, 14-17 November 2016 List of Participants 1 Samir ABBES 9 Sabah ALMOMIN (FTWAS) 18 Marlene BENCHIMOL Associate Professor Research Scientist Brazilian Academy of Sciences Higher Institute of Biotechnology of Beja Biotechnology Department Rio de Janeiro (ISBB) Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research Brazil Habib Bourguiba Street (KISR) BP: 382; Beja 9000 P.O. Box 24885 University of Jendouba Safat 13109 19 Tonya BLOWERS Jendouba 8189 Kuwait OWSD Programme Coordinator Tunisia Organization for Women in Science for 10 Ashima ANAND (FTWAS) the Developing World (OWSD) 2 Ahmed E. ABDEL MONEIM Principal Investigator c/o TWAS, ICTP Campus Lecturer Exertional Breathlessness Studies Strada Costiera 11 Zoology and Entomology Department Laboratory 34151 Trieste Faculty of Science Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute Italy Helwan University P.O. Box 2101 11795 Ain Helwan Delhi University 20 Rodrigo de Moraes BRINDEIRO Cairo Delhi 110 007 Director Egypt India Institute of Biology Federal University of Rio de Janeiro 3 Adejuwon Adewale ADENEYE 11 Asfawossen ASRAT KASSAYE (UFRJ) Associate Professor Associate Professor Rio de Janeiro Department of Pharmacology School of Earth Sciences Brazil Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences Addis Ababa University Lagos State University College of P.O. BOX 1176 21 Federico BROWN Medicine Addis Ababa Assistant Professor 1-5 Oba Akinjobi Way Ethiopia Departamento de Zoologia G.R.A. Ikeja, Lagos State, Nigeria Instituto de Biociências 12 Thomas AUF DER HEYDE Universidade de São Paulo 4 Ahmed A. AL-AMIERY Deputy Director General Rua do Matão, Travessa 14, n.101 Assistant Professor Ministry of Science and Technology Cidade Universitária Environmental Research Center Department of Science and Technology São Paulo SP. -

Stonybrook Estate Historic District Newport County, RI Name of Property County and State

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No.1 024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Stonvbrook Estate Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number 501 - 521 IndianAvenue and 75 Vaucluse Avenue 0 not for publication city or town Middletown 0 vicinity state RI code RI county Newport code 005 zip code _0_28_4_2 _ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this I:8J nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property o me~¢"¢\alkf 0 does0 stadide no~. ~lIy. NN~ationalRegister(0 See continuation criteria. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7.