CRISIS of PURPOSE in the IVY LEAGUE the Harvard Presidency of Lawrence Summers and the Context of American Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debating Diversity Following the Widely Publicized Deaths of Black Tape

KENNEDY SCHOOL, UNDER CONSTRUCTION. The Harvard Kennedy School aims to build students’ capacity for better public policy, wise democratic governance, international amity, and more. Now it is addressing its own capacity issues (as described at harvardmag.com/ hks-16). In January, as seen across Eliot Street from the northeast (opposite page), work was well under way to raise the level of the interior courtyard, install utility space in a new below-grade level, and erect a four-story “south building.” The project will bridge the Eliot Street opening between the Belfer (left) and Taubman (right) buildings with a new “gateway” structure that includes faculty offices and other spaces. The images on this page (above and upper right) show views diagonally across the courtyard from Taubman toward Littauer, and vice versa. Turning west, across the courtyard toward the Charles Hotel complex (right), affords a look at the current open space between buildings; the gap is to be filled with a new, connective academic building, including classrooms. Debating Diversity following the widely publicized deaths of black tape. The same day, College dean Toward a more inclusive Harvard African-American men and women at the Rakesh Khurana distributed to undergrad- hands of police. Particularly last semester, uates the results of an 18-month study on di- Amid widely publicized student protests a new wave of activism, and the University’s versity at the College. The day before, Presi- on campuses around the country in the last responses to it, have invited members of the dent Drew Faust had joined students at a year and a half, many of them animated by Harvard community on all sides of the is- rally in solidarity with racial-justice activ- concerns about racial and class inequities, sues to confront the challenges of inclusion. -

Harvard to Build New Campus Center; Donor Secured to Back Project - Harvard - Your Campus - Boston.Com

Harvard to build new campus center; donor secured to back project - Harvard - Your Campus - Boston.com MORE CAMPUSES Sign In | Register now HARVARD < Back to front page Text size – + Connect to Harvard HARVARD Follow @YCHarvard on Twitter Harvard to build new campus center; Click here to follow Your Campus Harvard on donor secured to back project Twitter. Posted by Matt Rocheleau September 19, 2013 01:05 PM ADVERTISEMENT 0 Comments (0) 1 1 0 E-mail story Print story Other Boston Area Campuses Facebook Twitter Pinterest Share Share Boston College Boston University By Matt Rocheleau, Town Correspondent Brandeis Emerson Harvard University will soon begin planning for a new campus center after securing Harvard MIT donor funding for the project, a campus official said. Northeastern Suffolk More details, including the identity of the donor, are expected to be released this fall, Tufts the official said, confirming a report last week by the Harvard Crimson student Wellesley newspaper, which quoted university president Drew Faust. UMass Boston Simmons Berklee Faust told the Crimson the new campus center will likely be constructed in the Holyoke Babson Center building and would include a range of spaces for community gatherings, Bentley parties, academic events, meetings, and studying. The donation for the project comes as part of a multi-year major fundraising campaign Recent blog posts called The Harvard Campaign, which was announced last spring and is scheduled to When does Spring Break start? A handy calendar for many formally launch on Saturday, Sept. 21, the official said. colleges Comcast testing new Internet-streamed TV service Planning for the project will include input from administrators, students, campus designed for college campuses at Emerson housing officials and faculty, the official said. -

The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports

By Ruth S. Barrett Th e Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports 74 Where the desperation of late-stage m 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 74 9/22/2020 12:04:44 PM Photo Illustrations by Pelle Cass Among Ivy League– Obsessed Parents meritocracy is so strong, you can smell it 75 1120_WEL_Barrett_TulipMania [Print]_14155638.indd 75 9/22/2020 12:04:46 PM On paper, Sloane, a buoyant, chatty, stay-at-home mom from Faireld County, Connecticut, seems almost unbelievably well prepared to shepherd her three daughters through the roiling world of competitive youth sports. She played tennis and ran track in high school and has an advanced “I thought, What are we doing? ” said Sloane, who asked to be degree in behavioral medicine. She wrote her master’s thesis on the identied by her middle name to protect her daughters’ privacy connection between increased aerobic activity and attention span. and college-recruitment chances. “It’s the Fourth of July. You’re She is also versed in statistics, which comes in handy when she’s ana- in Ohio; I’m in California. What are we doing to our family? lyzing her eldest daughter’s junior-squash rating— and whiteboard- We’re torturing our kids ridiculously. ey’re not succeeding. ing the consequences if she doesn’t step up her game. “She needs We’re using all our resources and emotional bandwidth for at least a 5.0 rating, or she’s going to Ohio State,” Sloane told me. a fool’s folly.” She laughed: “I don’t mean to throw Ohio State under the Yet Sloane found that she didn’t know how to make the folly bus. -

Edward Channing's Writing Revolution: Composition Prehistory at Harvard

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2017 EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 Bradfield dwarE d Dittrich University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Dittrich, Bradfield dwarE d, "EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 163. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH B.A. St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2003 M.A. Salisbury University, 2009 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May 2017 ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ©2017 Bradfield E. Dittrich iii EDWARD CHANNING’S WRITING REVOLUTION: COMPOSITION PREHISTORY AT HARVARD, 1819-1851 BY BRADFIELD E. DITTRICH This dissertation has been has been examined and approved by: Dissertation Chair, Christina Ortmeier-Hooper, Associate Professor of English Thomas Newkirk, Professor Emeritus of English Cristy Beemer, Associate Professor of English Marcos DelHierro, Assistant Professor of English Alecia Magnifico, Assistant Professor of English On April 7, 2017 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. -

A Nation at Risk

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform A Report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education United States Department of Education by The National Commission on Excellence in Education April 1983 April 26, 1983 Honorable T. H. Bell Secretary of Education U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202 Dear Mr. Secretary: On August 26, 1981, you created the National Commission on Excellence in Education and directed it to present a report on the quality of education in America to you and to the American people by April of 1983. It has been my privilege to chair this endeavor and on behalf of the members of the Commission it is my pleasure to transmit this report, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. Our purpose has been to help define the problems afflicting American education and to provide solutions, not search for scapegoats. We addressed the main issues as we saw them, but have not attempted to treat the subordinate matters in any detail. We were forthright in our discussions and have been candid in our report regarding both the strengths and weaknesses of American education. The Commission deeply believes that the problems we have discerned in American education can be both understood and corrected if the people of our country, together with those who have public responsibility in the matter, care enough and are courageous enough to do what is required. Each member of the Commission appreciates your leadership in having asked this diverse group of persons to examine one of the central issues which will define our Nation's future. -

Report Concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein's Connections to Harvard University

REPORT CONCERNING JEFFREY E. EPSTEIN’S CONNECTIONS TO HARVARD UNIVERSITY Diane E. Lopez, Harvard University Vice President and General Counsel Ara B. Gershengorn, Harvard University Attorney Martin F. Murphy, Foley Hoag LLP May 2020 1 INTRODUCTION On September 12, 2019, Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow issued a message to the Harvard Community concerning Jeffrey E. Epstein’s relationship with Harvard. That message condemned Epstein’s crimes as “utterly abhorrent . repulsive and reprehensible” and expressed “profound[] regret” about “Harvard’s past association with him.” President Bacow’s message announced that he had asked for a review of Epstein’s donations to Harvard. In that communication, President Bacow noted that a preliminary review indicated that Harvard did not accept gifts from Epstein after his 2008 conviction, and this report confirms that as a finding. Lastly, President Bacow also noted Epstein’s appointment as a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Psychology in 2005 and asked that the review address how that appointment had come about. Following up on President Bacow’s announcement, Vice President and General Counsel Diane E. Lopez engaged outside counsel, Martin F. Murphy of Foley Hoag, to work with the Office of General Counsel to conduct the review. Ms. Lopez also issued a message to the community provid- ing two ways for individuals to come forward with information or concerns about Epstein’s ties to Harvard: anonymously through Harvard’s compliance hotline and with attribution to an email ac- count established for that purpose. Since September, we have interviewed more than 40 individu- als, including senior leaders of the University, staff in Harvard’s Office of Alumni Affairs and Development, faculty members, and others. -

Lia Halloran

Martha Otero Lia Halloran Born: 1977 Chicago, IL Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA Assistant Professor of Art, Chapman University, Orange, CA Education: 2001 MFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1999 BFA, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 1998 Studio Art Centers International, Florence, Italy Solo Exhibitions: 2012 Sublimation | Transmutation, Martha Otero Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2010 Folding and Unfolding, Artisphere, Arlington VA The Only Way Out Is Through, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY * 2008 Dark Skate, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY Dark Skate Miami, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami, FL Dark Skate, LaMontagne Gallery, Boston, MA 101 California Street, San Francisco, CA 2007 Dark Skate, DCKT Contemporary, Pulse London, London, UK 2006 The World is Bound with Secret Knots, DCKT Contemporary, New York, NY 2005 And the Darkness Implies the Vastness, Sandroni Rey, Los Angeles, CA 2001 Aesthetic Confinement; MFA Thesis Exhibition, Yale University School of Art, Green Hall Gallery, New Haven, CT Group Exhibitions: 2012 Tilt-Shift L.A. New Queer Perspectives on the Western Edge, Luis de Jesus Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2011 Haunted: Contemporary Photography / Video / Performance, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain Universe City, The Fine Arts Gallery at CSULA, Los Angeles, CA Critical Faculties, Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, CA. Oniomania, Martha Otero Gallery, Los Angeles, CA X-TRA’s, 1 Image 1 Minute, Angelenos Present Significant Images, Ray Kurtzman Theater Creative Arts Agency, Los Angeles, CA 2010 Girls Just Want to Have Funds, P.P.O.W Gallery, New York, NY Haunted: Contemporary Photography / Video / Performance, Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Bilbao, Spain 820 N Fairfax Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90046 t. -

El Activista Regional

El Activista Regional Revista de Información y Educación Política del Comité Regional Primer Centenario Año 21, Número 231 Junio de 2020 Que quede claro: “La soberanía nacional reside esencial y originariamente en el pueblo. Todo poder público dimana del pueblo y se instituye para beneficio de éste. El pueblo tiene en todo tiempo el inalienable derecho de alterar o modificar la forma de su gobierno”. (Artículo 39 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos). Página 5 A pesar de los deseos gubernamentales, la riesgosa combinación de crisis sanitaria, económica y de seguridad no se detiene El Activista Regional 231 2 Junio de 2020 Índice -Editorial..…………………………..………………………..3 -10 de junio de 1971 siempre en nuestra memoria.-José -Dirigentes socialistas en la historia de México…….….….4 Antonio Rueda Márquez…………………………………..37 -La investigación clínica en COVID-19.-Dr. Gerardo -Pronunciamiento de sobrevivientes de la guerra sucia,10 Gamba...………..…………………………………………...12 de junio no se olvida...……………………………………...38 -En el escenario más sombrío de la ONU para México, -Recordando a Rafael Aguilar Talamantes en el 49 habría 600 mil muertes por COVID-19.-Alejandro….…..13 aniversario de su liberación...…………………...………...39 -Evolución y “fin” del Covid-19.- Dr. Octavio Obregón -El legasdo revolucionario de Carlos Ferra.-Manuel Díaz y Dr. David Delepine…………………………….…...14 Aguilar Mora……...………………………………………..40 -Covid-19 en México.-MOMPADE……………….……....15 -Falleció Nemí Hakel.- Edgard Sánchez Ramírez……….43 -Los datos de Covid-19 no cuadran, la cifra -

Classroom Design - Literature Review

Classroom Design - Literature Review PREPARED FOR THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON CLASSROOM DESIGN PROFESSOR MUNG CHIANG, CHAIR PRINCETON UNIVERSITY BY: LAWSON REED WULSIN JR. SUMMER 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In response to the Special Committee on spontaneous learning. So too does furnishing Classroom Design’s inquiry, this literature these spaces with flexible seating, tables for review has been prepared to address the individual study and group discussion, vertical question; “What are the current trends in surfaces for displaying student and faculty work, learning space design at Princeton University’s and a robust wireless network. peer institutions?” The report is organized into five chapters and includes an annotated Within the classroom walls, learning space bibliography. should be as flexible as possible, not only because different teachers and classes require The traditional transference model of different configurations, but because in order to education, in which a professor delivers fully engage in constructivist learning, students information to students, is no longer effective at need to transition between lecture, group preparing engaged 21st-century citizens. This study, presentation, discussion, and individual model is being replaced by constructivist work time. Furniture that facilitates rapid educational pedagogy that emphasizes the role reorganization of the classroom environment is students play in making connections and readily available from multiple product developing ideas, solutions, and questions. manufacturers. Already, teachers are creating active learning environments that place students in small work Wireless technology and portable laptop and groups to solve problems, create, and discover tablet devices bring the internet not just to together. every student’s dorm room, but also to every desk in the classroom. -

Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01 Kathy Sheehan Western Washington University

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Window on Western Western Publications Fall 1998 Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01 Kathy Sheehan Western Washington University Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices,es W tern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kathy and Alumni, Foundation, and Public Information Offices, Western Washington University, "Window on Western, 1998, Volume 05, Issue 01" (1998). Window on Western. 10. https://cedar.wwu.edu/window_on_western/10 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Window on Western by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fall 1998 WINDOWNews for Alumni and Friends of Western WashingtonON University WESTERNVOL 5, NO. 1 ' r.% am 9HI <•* iii m t 4 ; Professor Richard Emmerson, Olscamp award winner Kathy Sheehan photo A youthful curiosity leads to excellence rofessor Richard Emmerson's parents Emmerson, who came to Western in 1990 provided him with a good grounding as chair of the English department, has been in religious matters, helping him to conducting research on the Middle Ages for understand the Bible and biblical his nearly 30 years, including a year he spent tory, up to the early Christian church. Later, abroad during his undergraduate days. his high school history teachers taught him During his sophomore year in England, he American history, beginning, of course, with enrolled in his first English literature course 1492. -

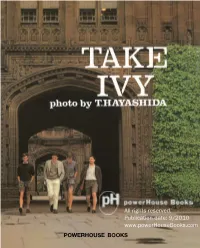

Take Ivy Was Originally Published Shosuke Ishizu Is the Representative Director in Japan in 1965, Setting Off an Explosion of of Ishizu Office

Teruyoshi Hayashida was born in the fashionable Aoyama District of Tokyo, where he also grew up. He began shooting cover images for Men’s Club magazine after the title’s launch. A sophisticated Photographs by Teruyoshi Hayashida dresser and a connoisseur of gourmet food, Text by Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, he is known for his homemade, soy-sauce- and Hajime (Paul) Hasegawa marinated Japanese pepper (sansho), and his love of gunnel tempura and Riesling wine. Described by The New York Times as, “a treasure of fashion insiders,” Take Ivy was originally published Shosuke Ishizu is the representative director in Japan in 1965, setting off an explosion of of Ishizu Office. Originally born in Okayama American-influenced “Ivy Style” fashion among Prefecture, after graduating from Kuwasawa Design students in the trendy Ginza shopping district School he worked in the editorial division at Men’s of Tokyo. The product of four collegiate style Club until 1960 when he joined VAN Jacket Inc. enthusiasts, Take Ivy is a collection of candid He established Ishizu Office in 1983, and now photographs shot on the campuses of America’s produces several brands including Niblick. elite, Ivy League universities. The series focuses on men and their clothes, perfectly encapsulating Toshiyuki Kurosu was raised in Tokyo. He joined the unique student fashion of the era. Whether VAN Jacket Inc. in 1961, where he was responsible lounging in the quad, studying in the library, riding for the development of merchandise and sales bikes, in class, or at the boathouse, the subjects of promotion. He left the company in 1970 and Take Ivy are impeccably and distinctively dressed in started his own business, Cross and Simon.