An Empirical Study of Subpoenas Received by the News Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Pearlstine, Chief Content Officer

Mandatory Credit: Bloomberg Politics and the Media Panel: Bridging the Political Divide in the 2012 Elections Breakfast NORMAN PEARLSTINE, CHIEF CONTENT OFFICER, BLOOMBERG, LP: Thank you very much to all of you for coming this afternoon for this panel discussion and welcome to the Bloomberg Link. This is a project that a number of my colleagues have been working very hard on to - to get in shape having had a similar facility in Tampa last week. And as Al Hunt is fond of reminding me, eight years ago, Bloomberg was sharing space as far away from the perimeter and I guess any press could be. I think sharing that space with Al Jazeera -- About four years ago, we certainly had a press presence in Denver and St. Paul, but this year, we're a whole lot more active and a lot more aggressive and I think that reflects all the things that Bloomberg has been doing to increase its presence in Washington where, in the last two years through an acquisition and a start up, we've gone from a 145 journalists working at Bloomberg News to close to 2,000 employees and that reflects in large part the acquisition of BNA last September but also the start up of Bloomberg Government, a web based subscription service. And so over the next few days, we welcome you to come back to the Bloomberg Link for a number of events and hopefully, you'll get a chance to meet a number of my colleagues in the process. I'm very happy that we are able to start our activities in Charlotte with this panel discussion today, not only because of the subject matter, which is so important to journalism and to politics, but also because, quite selfishly, it's given me a chance to partner with Jeff Cowan and Center for Communication Leadership and Policy in Los Angeles at Annenberg USC, which Jeff, I was happy to be a co-chair of your board so, it's good to be able to - each of us to convince the other we ought to do this. -

Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: a Question of Access

690 American Archivist / Vol. 56 / Fall 1993 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/56/4/690/2748590/aarc_56_4_w213201818211541.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Question of Access SARA S. HODSON Abstract: The announcement by the Huntington Library in September 1991 of its decision to open for unrestricted research its photographs of the Dead Sea Scrolls touched off a battle of wills between the library and the official team of scrolls editors, as well as a blitz of media publicity. The action was based on a commitment to the principle of intellectual freedom, but it must also be considered in light of the ethics of donor agreements and of access restrictions. The author relates the story of the events leading to the Huntington's move and its aftermath, and she analyzes the issues involved. About the author: Sara S. Hodson is curator of literary manuscripts at the Huntington Library. Her articles have appeared in Rare Books & Manuscripts Librarianship, Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook, and the Huntington Library Quarterly. This article is revised from a paper delivered before the Manuscripts Repositories Section meeting of the 1992 Society of American Archivists conference in Montreal. The author wishes to thank William A. Moffett for his encour- agement and his thoughtful and invaluable review of this article in its several revisions. Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls 691 ON 22 SEPTEMBER 1991, THE HUNTINGTON scrolls for historical scholarship lies in their LIBRARY set off a media bomb of cata- status as sources contemporary with the time clysmic proportions when it announced that they illuminate. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

February 4, 2010

February 4, 2010 475 PARK AVENUE SOUTH, NEW YORK, NY 10016 TEL (212) 686-9700 FAX (212) 686-2172 WWW.MEDIABANKERS.COM Lorne Manly Entertainment Editor Mr. Manly is the entertainment editor of The New York Times. In this role, he oversees the cultural coverage of movies, television and videogames, both in the paper and online. Previously, Mr. Manly was the paper’s film editor, responsible for movie news, feature and reviews; chief media writer, covering trends across the media, entertainment and technology landscapes; and media editor, charged with coverage of the magazine, newspaper, television, movie, music, book publishing and advertising worlds. Before joining The Times in 2002, Mr. Manly worked at Inside as the media editor for its web site, Inside.com, and as the executive editor for its magazine, and served as editorial director for Folio. Mr. Manly has also worked at Brill’s Content as a senior writer and The New York Observer as its media columnist. He began his journalism career at the Toronto Star as a general assignment reporter. Mr. Manly received a BA in political science and history from York University in Toronto, Canada, and graduated with a MS from the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. Keynote Interview Kevin Mayer was appointed executive vice president of Corporate Strategy, Business Development and Technology in June 2005. Mayer leads the group as it targets emerging businesses new to Disney's existing portfolio, manages cross-divisional issues and opportunities, and evaluates new technology and business models. The group is also Kevin Mayer responsible for the evaluation and execution EVP, Corporate Strategy, of mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

Do I Owe Israel Support of Nixon?

killed not him alone, but much more. It killed a dream, morality. We helped by joining forces with destructive and woke me up to the horrible reality in which we hate-mongers, who talk about an Utopian world, but in Jews live. times of real need are incapable of human decency and feelings. We dreamt of a United Nations — about an^nlightened world opinion. Where were they when the Arabs seemed May the untimely death and sacrifice of our Israeli to be victorious? Only when the Arabs seemed beaten brethren be a warning to all of us before it is too late. did the United Nations awake and spread its protective umbrella to prevent Egypt from suffering the results of its aggression. Where, were all those great humanist Do i owe israel support of nixon? nations that were so concerned about Vietnam? Not a single one spoke out — all being more concerned with Jonathan Groner oil than with elementary human decency. How would the impeachment or resignation of the Where was the great McGovern, when his friend Fulbright President affect the future of Israel, and therefore, gave an anti-semitic speech worthy of a Goebbels? And how are we as Jews to respond to calls for either? where were all the great liberal columnists from the New York Times? Only William Safire found it appro- It is clear that if the removal of Richard Nixon would priate to express a word of encouragement. Had we directly endanger Israel's security — for example, if a been criminals, maybe a Tom Wicker or an Anthony Fulbright stood to succeed him — we would have to Lewis would have found time to shed a fake tear — but support Nixon and swallow our revulsion. -

Torturing Terrorists for National Security Imperatives: Mediated Violence on "24"

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2009 Torturing terrorists for national security imperatives: Mediated violence on "24" Michael D. Sears University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Television Commons Repository Citation Sears, Michael D., "Torturing terrorists for national security imperatives: Mediated violence on "24"" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1183. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2596826 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TORTURING TERRORISTS FOR NATIONAL SECURITY IMPERATIVES: MEDIATED VIOLENCE ON 24 by Michael D. Sears Bachelor of Arts New Mexico State University 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Journalism and Media Studies Hank Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2009 UMI Number: 1472488 Copyright 2009 by Sears, Michael D. -

Social Meaning and School Vouchers

William & Mary Law Review Volume 42 (2000-2001) Issue 3 Institute of Bill of Rights Symposium: Article 9 Religion in the Public Square March 2001 Social Meaning and School Vouchers Neal Devins William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Repository Citation Neal Devins, Social Meaning and School Vouchers, 42 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 919 (2001), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol42/iss3/9 Copyright c 2001 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr SOCIAL MEANING AND SCHOOL VOUCHERS NEAL DEvINs* The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same: In 1981, I wrote a paper on the constitutionality of school vouchers for a law school course. At the time, it appeared that a sharply divided Supreme Court would reject vouchers, five to four. Two decades later, it appears that a sharply divided Supreme Court might well uphold vouchers, five to four. For this very reason, academics and others continue to fill the pages of law reviews with competing analyses of whether school vouchers violate the Establishment Clause.' Far more tellingly, during the 2000 elections, Court watchers claimed that the winner of the presidential race would control the constitutional fate of school vouchers (by, presumably, appointing the Justice who will cast the deciding vote in a constitutional challenge to school vouchers).2 * Goodrich Professor of Law and Lecturer in Public Policy, College of William & Mary. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

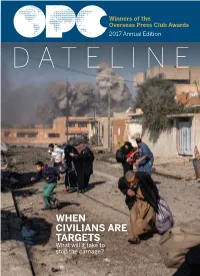

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

2015 New York Journalism Hall of Fame

THE DEADLINE CLUB New York City Chapter, Society of Professional 2015 Journalists NEW YORK JOURNALISM HALL OF FAME SARDI’S RESTAURANT, 234 WEST 44TH ST., MANHATTAN Thursday, Nov. 19, 2015 11:30 a.m. reception Noon luncheon 1 p.m. ceremony PROGRAM WELCOME J. Alex Tarquinio MENU Deadline Club Chairwoman REMARKS APPETIZER Peter Szekely Deadline Club President Sweet Corn Soup with Crab and Avocado Paul Fletcher ENTREE Society of Professional Journalists President Sauteed Black Angus Sirloin Steak with Parmesan Whipped Potatoes, Betsy Ashton Porcini Parsley Custard and Classic Bordelaise Sauce, Deadline Club Past President Seasonal Vegetables THE HONOREES MAX FRANKEL DESSERT The New York Times Molten Chocolate Cake JUAN GONZÁLEZ with Pistachio Ice Cream The New York Daily News CHARLIE ROSE CBS and PBS LESLEY STAHL CBS’s “60 Minutes” PAUL E. STEIGER ProPublica and The Wall Street Journal RICHARD B. STOLLEY Time Inc. FOLLOW THE CONVERSATION ON TWITTER WITH THE HASHTAG #deadlineclub. PROGRAM WELCOME J. Alex Tarquinio MENU Deadline Club Chairwoman REMARKS APPETIZER Peter Szekely Deadline Club President Sweet Corn Soup with Crab and Avocado Paul Fletcher ENTREE Society of Professional Journalists President Sauteed Black Angus Sirloin Steak with Parmesan Whipped Potatoes, Betsy Ashton Porcini Parsley Custard and Classic Bordelaise Sauce, Deadline Club Past President Seasonal Vegetables THE HONOREES MAX FRANKEL DESSERT The New York Times Molten Chocolate Cake JUAN GONZÁLEZ with Pistachio Ice Cream The New York Daily News CHARLIE ROSE CBS and PBS LESLEY STAHL CBS’s “60 Minutes” PAUL E. STEIGER ProPublica and The Wall Street Journal RICHARD B. STOLLEY Time Inc. FOLLOW THE CONVERSATION ON TWITTER WITH THE HASHTAG #deadlineclub.