Norman Pearlstine, Chief Content Officer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 4, 2010

February 4, 2010 475 PARK AVENUE SOUTH, NEW YORK, NY 10016 TEL (212) 686-9700 FAX (212) 686-2172 WWW.MEDIABANKERS.COM Lorne Manly Entertainment Editor Mr. Manly is the entertainment editor of The New York Times. In this role, he oversees the cultural coverage of movies, television and videogames, both in the paper and online. Previously, Mr. Manly was the paper’s film editor, responsible for movie news, feature and reviews; chief media writer, covering trends across the media, entertainment and technology landscapes; and media editor, charged with coverage of the magazine, newspaper, television, movie, music, book publishing and advertising worlds. Before joining The Times in 2002, Mr. Manly worked at Inside as the media editor for its web site, Inside.com, and as the executive editor for its magazine, and served as editorial director for Folio. Mr. Manly has also worked at Brill’s Content as a senior writer and The New York Observer as its media columnist. He began his journalism career at the Toronto Star as a general assignment reporter. Mr. Manly received a BA in political science and history from York University in Toronto, Canada, and graduated with a MS from the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. Keynote Interview Kevin Mayer was appointed executive vice president of Corporate Strategy, Business Development and Technology in June 2005. Mayer leads the group as it targets emerging businesses new to Disney's existing portfolio, manages cross-divisional issues and opportunities, and evaluates new technology and business models. The group is also Kevin Mayer responsible for the evaluation and execution EVP, Corporate Strategy, of mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures. -

Tech Edit Spotlight: the Wall Street Journal May 2009

SWMS Editorial Teleconference Series: Tech Edit Spotlight: The Wall Street Journal May 2009 Well into its second year under the stewardship of News Corp., the Wall Street Journal remains an enigma. Its circulation has risen when virtually all competitors have retrenched. Most PR pros still view it as the place to be. But underneath the mighty brand, edit quality has slipped. Typos. Less thought leadership. Departures of key talent. But things could be worse. Iironically for those who feared the worst from Rupert Murdoch, only News Corp.’s deep pockets have kept the WSJ from the fiscal pain affecting every other newspaper in America. The WSJ remains the most powerful editorial brand there is. SWMS Webinar Link The Mission From a business standpoint, the WSJ cares about the collision of telecom- munications and computing as it affects society. And in The Journal’s esti- mation, society is all about markets. Retailing, customer service... technol- ogy, and particularly communications technologies have radically trans- formed every single business there is, which is why The Wall Street Journal cares about it. Kill The Times, Kill The Post, and don’t be boring. Write breaking news. Priority #1: Beat The New York Times. Priority #2: Marcus Brauchli and The Washington Post. Brauchli is a former Wall Street Jour- SWMS Teleconference nal managing editor. There seems to be a personal vendetta going on, not only to take down Links & Insight The New York Times, but Murdoch also intends to put pressure on The Washington Post as well by putting the resources in Washington D.C. -

130556 IOP.Qxd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY John F. WINTER 2003 Kennedy School of Message from the Director INSTITUTE Government Spring 2003 Fellows Forum Renaming New Members of Congress OF POLITICS An Intern’s Story Laughter in the Forum: Jon Stewart on Politics and Comedy Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University D AN G LICKMAN, DIRECTOR The past semester here at the Institute brought lots of excitement—a glance at this newsletter will reveal some of the fine endeavors we’ve undertaken over the past months. But with a new year come new challenges. The November elections saw disturbingly low turnout among young voters, and our own Survey of Student Attitudes revealed widespread political disengagement in American youth. This semester, the Institute of Politics begins its new initiative to stop the cycle of mutual dis- engagement between young people and the world of politics. Young people feel that politicians don’t talk to them; and we don’t. Politicians know that young people don’t vote; and they don’t. The IOP’s new initiative will focus on three key areas: participation and engagement in the 2004 elections; revitalization of civic education in schools; and establishment of a national database of political internships. The students of the IOP are in the initial stages of research to determine the best next steps to implement this new initiative. We have experience To subscribe to the IOP’s registering college students to vote, we have had success mailing list: with our Civics Program, which sends Harvard students Send an email message to: [email protected] into community middle and elementary schools to teach In the body of the message, type: the importance of government and politics. -

2014-2015 Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT 2014-2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION ABOUT THE IWMF Our mission is to unleash the potential of women journalists as champions of press freedom to transform the global news media. Our vision is for women journalists worldwide to be fully supported, protected, recognized and rewarded for their vital contributions at all levels of the news media. As a result, consumers will increase their demand for news with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives as a cornerstone of democracy and free expression. Photo: IWMF Fellow Sonia Paul Reporting in Uganda 2 IWMF IMPACT REPORT 2014/2015 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION IWMF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Linda Mason, Co-Chair CBS News (retired) Dear Friends, Alexandra Trower, Co-Chair We are honored to lead the IWMF Board of Directors during this amazing period of growth and renewal for our The Estée Lauder Companies, Inc. Cindi Leive, Co-Vice Chair organization. This expansion is occurring at a time when journalists, under fire and threats in many parts of the Glamour world, need us most. We’re helping in myriad ways, including providing security training for reporting in conflict Bryan Monroe, Co-Vice Chair zones, conducting multifaceted initiatives in Africa and Latin America, and funding individual reporting projects Temple University that are being communicated through the full spectrum of media. Eric Harris, Treasurer Cheddar We couldn’t be more proud of how the IWMF has prioritized smart and strategic growth to maximize our award George A. Lehner, Legal Counsel and fellowship opportunities for women journalists. Through training, support, and opportunities like the Courage Pepper Hamilton LLP in Journalism Awards, the IWMF celebrates the perseverance and commitment of female journalists worldwide. -

It Takes a Journalist

IT TAKES A JOURNALIST ® 2019 ANNUAL REVIEW IT TAKES A OUR MISSION LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT JOURNALIST ® ICFJ empowers a global network of Dear Friend, 2 OUR MISSION journalists to produce news coverage Across the globe, our unparalleled network of journalists produces news stories 3 LETTER FROM OUR PRESIDENT that have tremendous impact. With our training and support, these journalists: 4 BLAZING THE TRAIL that leads to better governments, Hold the powerful to account even in the darkest corners of the world 6 OUR NETWORK stronger economies, vibrant societies where autocratic forces threaten their safety. 8 OUR IMPACT and healthier lives. Combat disinformation as fake news spreads across every platform — 12 AWARDS DINNER from local radio in the smallest village to the social media giants. 15 FINANCIALS 16 OUR DONORS Give voice to the forgotten, such as poor children denied an ICFJ HAS WORKED WITH education or women deformed in vicious acid attacks. 19 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 140,000+ JOURNALISTS On our 35th anniversary, we are committed to expanding our vast network of journalists, who are pursuing the truth despite the risks. FROM 180 COUNTRIES Join our efforts to support the truth tellers in these perilous times. To ensure free and vibrant societies, it takes a journalist. OVER 35 YEARS Joyce Barnathan, President, ICFJ ICFJ 2019 ANNUAL REVIEW 3 BLAZING THE TRAIL ICFJ has stayed ahead of the trends to ensure that journalists can provide the highest quality content. 1984 1989 1994 2001 2007 2009 2010 2014 2016 2017 2018 2018 2019 Founded by Led the rise of Trained a new Helped U.S. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

Article Racial Capitalism

VOLUME 126 JUNE 2013 NUMBER 8 © 2013 by The Harvard Law Review Association ARTICLE RACIAL CAPITALISM Nancy Leong CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2153 I. VALUING RACE ................................................................................................................... 2158 A. Whiteness as Property .................................................................................................... 2158 B. Diversity as Revaluation ................................................................................................ 2161 C. The Worth of Nonwhiteness .......................................................................................... 2169 II. A THEORY OF RACIAL CAPITALISM .............................................................................. 2172 A. Race as Social Capital .................................................................................................... 2175 B. Race as Marxian Capital ............................................................................................... 2183 C. Racial Capitalism ............................................................................................................ 2190 III. CRITIQUING RACIAL CAPITALISM ................................................................................. 2198 A. Commodification ............................................................................................................. 2199 B. Harm -

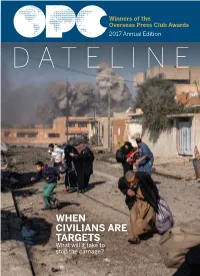

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

Framing Disabilities Symposium Proceedings 2

The Georgetown University According to the US Census Bureau, 54 million Americans have a Center for Child and disability, representing 18% of the population. Between 1990 and 2000, Human Development the number of Americans with disabilities increased 25 percent, http://gucchd.georgetown.edu outpacing any other subgroup of the U.S. population. With an aggregate income of $1 trillion and $220 billion of discretionary spending, people with disabilities are an often-ignored market. Media, especially news organizations, has the ability to raise awareness, clarify information, and educate the public on issues as diverse as The School of Continuing foreign policy and fashion. Although mass media has the potential to Studies, Journalism “socially construct images of people with disabilities” positively, in reality The Master of Professional Studies in it often perpetuates stereotypes by depicting individuals with disabilities Journalism degree program as dependent, helpless, burdens, threats, or heroes. According to the Special Olympics more than 80% of US adults surveyed felt that media portrayals were an obstacle to acceptance and inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. This symposium explored issues related to the representation of persons with disabilities in the media and how this representation influences the public’s attitudes and perpetuate stereotypes, which in turn influence decisions regarding school placement, employment opportunities, Proceedings Edited By: housing choices, use of public transportation, access to health -

The Front Runner

The Front Runner Written by Matt Bai & Jay Carson & Jason Reitman July 27th, 2017 Blue Revisions 8/28/17 Pink Revisions 9/10/17 Yellow Revisions 9/15/17 ii. Note: The following screenplay features overlapping dialogue in the style of films like The Candidate. The idea is to create a true-to-life experience of the Hart campaign of 1987. CAST OF CHARACTERS THE HARTS GARY HART, SENATOR LEE HART, HIS WIFE THE CAMPAIGN TEAM BILL DIXON, CAMPAIGN MANAGER BILLY SHORE, AIDE-DE-CAMP KEVIN SWEENEY, PRESS SECRETARY JOHN EMERSON, DEPUTY CAMPAIGN MANAGER DOUG WILSON, POLICY AIDE MIKE STRATTON, LEAD ADVANCE MAN IRENE KELLY, SCHEDULER AT THE WASHINGTON POST BEN BRADLEE, EXECUTIVE EDITOR ANN DEVROY, POLITICAL EDITOR AJ PARKER, POLITICAL REPORTER DAVID BRODER, CHIEF POLITICAL CORRESPONDENT BOB KAISER, MANAGING EDITOR AT THE MIAMI HERALD KEITH MARTINDALE, EXECUTIVE EDITOR JIM SAVAGE, EDITOR TOM FIEDLER, POLITICAL REPORTER JOE MURPHY, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER ROY VALENTINE, PHOTOGRAPHER THE TRAVELING PRESS JACK GERMOND, BALTIMORE SUN COLUMNIST IRA WYMAN, AP PHOTOGRAPHER ALAN WEINBERG, PHILADELHIA ENQUIRER ANN MCDANIEL, NEWSWEEK MIKE SHANAHAN, AP MIAMI DONNA RICE, MODEL AND ACTRESS BILLY BROADHURST, HART’S PERSONAL FRIEND LYNN ARMANDT, RICE’S FRIEND “1984” EXT. SAINT FRANCIS HOTEL, SAN FRANCISCO. NIGHT. We open inside a NEWS VAN. Four monitors show different competing feeds. A waiting reporter. Color Bars. A political commercial. One monitor is cueing up a debate clip. A light pops on the reporter and he springs to life. TV REPORTER Yes, we learned just a few minutes ago that Senator Hart will soon be leaving this hotel back to the convention hall, where he will concede -- yes, he will concede -- to former vice president Walter Mondale. -

Download Transcript

THE ECONOMIC CLUB OF WASHINGTON, D.C. A CONVERSATION WITH DONALD GRAHAM WELCOME AND MODERATOR: DAVID RUBENSTEIN, PRESIDENT AND CEO, THE ECONOMIC CLUB OF WASHINGTON, D.C. SPEAKER: DONALD E. GRAHAM, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD, THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY TUESDAY, MARCH 2, 2010 Transcript by Federal News Service Washington, D.C. DAVID RUBENSTEIN: Can everybody please take their seats? Can everybody please take their seats? Is this mike on? It doesn’t feel like it. Can everybody please take their seats so we can start on time? MR. : You’ve got a lot of influence here. MR. RUBENSTEIN: I have none, none. I have no influence. Nobody ever listens. It is like talking to your kids. Okay. Could we close the doors and people please sit down? Thank you all for sitting down. Okay, we are making progress. Thank you. How many people here did not get the word that the last month’s event was cancelled and showed up? There were a few. Okay, I’m sorry. We made a very late decision to cancel last month’s event with Don. I now know what it is like to, you know, be a school superintendent and try to figure out whether schools are going to be open or not. I talked to Don late that night and we didn’t know whether it was going to snow, wasn’t going to snow the next day. We went back and forth and actually it didn’t snow at the time the event was held. But anyway, I apologize to those people who came.