Chapter 6: Sex Crime ❖ 193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bdsm) Communities

BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES A Thesis by Anita Fulkerson Bachelor of General Studies, Wichita State University, 1993 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Anita Fulkerson All Rights Reserved Note that thesis work is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. Only the author has the legal right to publish, produce, sell, or distribute this work. Author permission is needed for others to directly quote significant amounts of information in their own work or to summarize substantial amounts of information in their own work. Limited amounts of information cited, paraphrased, or summarized from the work may be used with proper citation of where to find the original work. BOUND BY CONSENT: CONCEPTS OF CONSENT WITHIN THE LEATHER AND BONDAGE, DOMINATION, SADOMASOCHISM (BDSM) COMMUNITIES The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies _______________________________________ Ron Matson, Committee Chair _______________________________________ Linnea Glen-Maye, Committee Member _______________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member _______________________________________ Patricia Phillips, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my Ma'am, my parents, and my Leather Family iv When you build consent, you build the Community. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Ron Matson, for his unwavering belief in this topic and in my ability to do it justice and his unending enthusiasm for the project. -

E Section/167-180

Book Reviews VIOLENCE IN THE find a variety of expressions in lan- intent of the volume, all three chap- NAME OF HONOR: guage, law, religion, education, cul- ters require the reader to contextualize THEORETICAL AND ture, the popular media and more. In their analyses and understanding in their introductory chapter, Mojab culturally specific ways, while keep- POLITICAL and Abdo identify several factors that ing in mind, as Abdo explains, the CHALLENGES mitigate our understanding (even if historical, structural and institutional to limit it) of femicide. Broadly stated, levels of society to more fully under- Shahrzad Mojab and Nahla Abdo, they are as follows: the androcentric stand the propagation of such crimes. Eds. nature of gender relations; legal and Additionally, the contributors to this Istanbul: Istanbul Bilgi University extra-legal inequalities that exist; the section ask us to look closely at the Library Press, 2004 state’s reluctance to educate and in- socio-economic, political, and juridi- tervene; Western racist tendencies cal forces of the state that come into REVIEWED BY NADERA that identify male violence as an en- play when examining the causes and SHALHOUB KEVORKIAN demic component of the “nature” of effects of gender violence. Abdo pays the Other. As Mojab and Abdo state particular attention to the colonial in their introduction, femicide, or as legacy of gender violence, and Sirman The volume of collected essays, Vio- they name it, “violence in the name looks at the post-colonial state. lence In the Name of Honor, advo- of honor,” carries a “complex web of Elden’s contribution pays particular cates for feminist analyses that would contradictions between conscious- attention to the voices of actual enable the development of a femi- ness and reality, knowledge and prac- women who have been victims and nist epistemology regarding the crime tice, the individual and the state, the survivors of gender violence. -

Sexually Violent Predator” Commitment

Oklahoma Law Review Volume 67 Number 4 2014 Dangerous Diagnoses, Risky Assumptions, and the Failed Experiment of “Sexually Violent Predator” Commitment Deirdre M. Smith University of Maine School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Law and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Deirdre M. Smith, Dangerous Diagnoses, Risky Assumptions, and the Failed Experiment of “Sexually Violent Predator” Commitment, 67 OKLA. L. REV. 619 (2015), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol67/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oklahoma Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dangerous Diagnoses, Risky Assumptions, and the Failed Experiment of “Sexually Violent Predator” Commitment Cover Page Footnote I am grateful to the following people who read earlier drafts of this article and provided many helpful insights: David Cluchey, Malick Ghachem, Barbara Herrnstein Smith, and Jenny Roberts. I also appreciate the comments and reactions of the participants in the University of Maine School of Law Faculty Workshop, February 2014, and the participants in the Association of American Law Schools Section on Clinical Legal Education Works in Progress Session, May 2014. I am appreciative of Dean Peter Pitegoff for providing summer research support and of the staff of the Donald L. Garbrecht Law Library for its research assistance. This article is available in Oklahoma Law Review: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/olr/vol67/iss4/1 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 67 SUMMER 2015 NUMBER 4 DANGEROUS DIAGNOSES, RISKY ASSUMPTIONS, AND THE FAILED EXPERIMENT OF “SEXUALLY VIOLENT PREDATOR” COMMITMENT * DEIRDRE M. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

NECROPHILIC and NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page

Running head: NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page: Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Christina Molinari Approved: August 2005 Dr. David Thomas Committee Chair / Advisor Dr. Shawn Keller Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 1 Necrophilic and Necrophagic Serial Killers: Understanding Their Motivations through Case Study Analysis Christina Molinari Florida Gulf Coast University NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7 Serial Killing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Characteristics of sexual serial killers ..................................................................................... 8 Paraphilia ................................................................................................................................... 12 Cultural and Historical Perspectives -

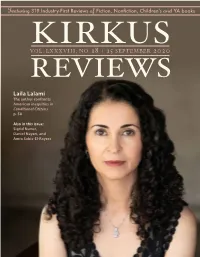

Kirkus Reviews on Our Website by Logging in As a Subscriber

Featuring 319 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books VOL.KIRKUS LXXXVIII, NO. 18 | 15 SEPTEMBER 2020 REVIEWS Laila Lalami The author confronts American inequities in Conditional Citizens p. 58 Also in this issue: Sigrid Nunez, Daniel Nayeri, and Amra Sabic-El-Rayess from the editor’s desk: The Way I Read Now Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # Among the many changes in my daily life this year—working from home, Chief Executive Officer wearing a mask in public, watching too much TV—my changing read- MEG LABORDE KUEHN ing habits register deeply. For one thing, I read on a Kindle now, with the [email protected] Editor-in-Chief exception of the rare galley sent to me at home and the books I’ve made TOM BEER a point of purchasing from local independent bookstores or ordering on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing Bookshop.org. The Kindle was borrowed—OK, confiscated—from my SARAH KALINA boyfriend at the beginning of the pandemic, when I left dozens of advance [email protected] reader copies behind at the office and accepted the reality that digital gal- Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU leys would be a practical necessity for the foreseeable future. I can’t say that I [email protected] love reading on my “new” Kindle—I’m still a sucker for physical books after Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK all these years—but I’ll admit that it fulfills its purpose efficiently. And I do [email protected] Tom Beer rather enjoy the instant gratification of going on NetGalley or Edelweiss Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH and dispatching multiple books to my device in one fell swoop—a harmless [email protected] form of bingeing that affords a little dopamine rush. -

The Case of J Effrey Dah M Er

5 THE CASE OF J EFFREY DAH M ER OVERVIEW This chapter specifically addresses the highly publicized case of Jeffrey Dahmer, a serial lust murderer responsible for the death and mutilation of 17 young men. In an attempt to create a working profile, several factors linked to Dahmer's social and family history, sexuality, education, employment status, fantasy system, and criminality are discussed. In Chapter 6, this developmental portrait is linked to the three principal theoretical models discussed within Chapters 3 and 4. Specifically, Chapter 6 explores what insights the motivational, trauma control, and integrative paraphilic typologies offer in their accounts of Jeffrey Dahmer's criminal behavior. This exercise is particularly useful since the goal is to ascertain the extent to which each conceptual schema advances our understanding of serial sexual homicide (i.e., lust murder) and those persons who commit this act. This chapter is divided into two sections. First, several methodological issues germane to our overall assessment of Jeffrey Dahmer are delineated. Given that our approach emphasizes the case study investigatory strategy, a number of remarks relevant to this line of analysis are warranted. Some observations regard- ing the elements of the case study method are specified, several justifications for the selection of a qualitative approach are outlined, and a description of the data is supplied. Second, both historical and biographical information concerning Dahmer's life is provided. These data are sequenced chronologically, commencing with his early childhood development and moving all the way to his violent fantasies, criminal conduct, and paraphilic behaviors. Profiling his case in this way allows 67 68 THE PSYCHOLOGY OF LUST MURDER the reader to assess the merits of the general organization and facilitates a more comprehensive and seamless evaluation within the application work undertaken in Chapter 6. -

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970

Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lvovsky, Anna. 2015. Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge About Homosexuality, 1920–1970. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463142 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 A dissertation presented by Anna Lvovsky to The Committee on Higher Degrees in the History of American Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of American Civilization Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Anna Lvovsky All rights reserved. Advisor: Nancy Cott Anna Lvovsky Queer Expertise: Urban Policing and the Construction of Public Knowledge about Homosexuality, 1920–1970 Abstract This dissertation tracks how urban police tactics against homosexuality participated in the construction, ratification, and dissemination of authoritative public knowledge about gay men in the -

Exploring Racial Bias in Print Media Coverage of Serial Rape Cases

BLACK, WHITE, AND READ ALL OVER: EXPLORING RACIAL BIAS IN PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF SERIAL RAPE CASES by LAUREN ELIZABETH WRIGHT B.A. Ohio University, 2010 M.A. Ohio University, 2014 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2017 Major Professor: Lin Huff-Corzine © 2017 Lauren Elizabeth Wright ii ABSTRACT The discussion of race and crime has been a long-standing interest of researchers, with statistics consistently showing an overrepresentation of non-white offenders compared to their white counterparts – specifically in relation to violent crimes such as murder and rape. Prior research has found that about 46 percent of serial rapists are black, a fact that correlates with other sensationalized violent crimes such as mass murder and serial murder. The news media are the primary sources of this kind of information for the general public, with previous studies acknowledging that the media primarily focus on discussing non-white offenders in their crime- based news stories. With the majority of Americans receiving their information about crime from the news media, it is important to increase our understanding of how their representations might influence the general public. The current study explores the print media representations of serial rapists, from 1940-2010, from five newspapers: The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and the Chicago Tribune. A content analysis was conducted on 524 articles covering 297 serial rape offenders from the data compiled by Wright, Vander Ven, and Fesmire (2016) in which race of the offender was known. -

Curing Sexual Deviance : Medical Approaches to Sexual Offenders in England, 1919-1959

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output Curing sexual deviance : medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959 http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/188/ Version: Full Version Citation: Weston, Janet (2016) Curing sexual deviance : medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of Lon- don. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email Curing sexual deviance Medical approaches to sexual offenders in England, 1919-1959 Janet Weston Department of History, Classics, and Archaeology Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 1 Declaration: I confirm that all material presented in this thesis is my own work, except where otherwise indicated. Signed ............................................... 2 Abstract This thesis examines medical approaches to sexual offenders in England between 1919 and 1959. It explores how doctors conceptualised sexual crimes and those who committed them, and how these ideas were implemented in medical and legal settings. It uses medical and criminological texts alongside information about specific court proceedings and offenders' lives to set out two overarching arguments. Firstly, it contends that sexual crime, and the sexual offender, are useful categories for analysis. Examining the medical theories that were put forward about the 'sexual offender', broadly defined, and the ways in which such theories were used, reveals important features of medico-legal thought and practice in relation to sexuality, crime, and 'normal' or healthy behaviour. -

The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified

Arch Sex Behav DOI 10.1007/s10508-009-9552-0 ORIGINAL PAPER The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified Martin P. Kafka Ó American Psychiatric Association 2009 Abstract The category of ‘‘Not Otherwise Specified’’ (NOS) Introduction for DSM-based psychiatric diagnosis has typically retained diag- noses whose rarity, empirical criterion validation or symptomatic Prior to an informed discussion of the residual category for expression has been insufficient to be codified. This article re- paraphilic disorders, Paraphilia Not Otherwise Specified (PA- views the literature on Telephone Scatologia, Necrophilia, Zoo- NOS), it is important to briefly review the diagnostic criteria philia, Urophilia, Coprophilia, and Partialism. Based on extant for a categorical diagnosis of paraphilic disorders as well as the data, no changes are suggested except for the status of Partialism. types of conditions reserved for the NOS designation. Partialism, sexual arousal characterized by ‘‘an exclusive focus The diagnostic criteria for paraphilic disorders have been mod- on part of the body,’’ had historically been subsumed as a type of ified during the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Man- Fetishism until the advent of DSM-III-R. The rationale for con- uals of the American Psychiatric Association. In the latest edition, sidering the removal of Partialism from Paraphilia NOS and its DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), a para- reintegration as a specifier for Fetishism is discussed here and in a philic disorder must meet two essential criteria. The essential companion review on the DSM diagnostic criteria for fetishism features of a Paraphilia are recurrent, intense sexually arousing (Kafka, 2009). -

1 Megan's Law and the Misconception of Sex Offender Recidivism1 Debra

Megan’s Law and the misconception of sex offender recidivism1 Debra Patkin 1 I would like to thank Professor Lynn M. LoPucki, Tayler Mayer, and Lesley Patkin for their support, help, and guidance in writing this paper. 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...3 II. Sex Offender Legislations and Recidivism……………………………………………4 A. Sex crime and panic…………………………………………………………..…6 B. Megan’s Laws are largely based on so-called high recidivism…………………8 III. Megan’s Laws should not be based on a collection of recidivism studies in which there is no consensus………………………………………………………13 A. Different studies, different conclusions………………………………………..14 i. Differ by Methodology…………………………………………………..15 ii. Differ by Crime/Victims/Offender………………………………………19 iii. Differ by Individual Factors……………………………………………...21 B. Laws justified by recidivism rates of stranger offenders while the majority of victims know their offenders………………………..25 C. The great harms of the laws should be narrowly tailored………………….27 IV. Why the justifications for Megan’s Laws fail………………………………………30 V. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..34 2 I. Introduction Legislatures cite the so-called high recidivism rate of sex offenders to implement Megan’s Laws to justify laws requiring sex offenders to register and having their information being disseminated to the community. However, whether people convicted of sex crimes actually possess a dangerous risk of recidivism remains doubtful. This paper will critically question the justification of reliance on recidivism studies by both state and federal legislatures in implementing Megan’s Laws. Part II outlines the history of Megan’s Laws and presents the claims of recidivisms made by the legislatures. Part III first demonstrates how Megan’s laws do not take in account the variation in recidivism rates among studies.