Mackenzie King's Campaign to Prepare Canada For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A THREAT to LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King

S. Peter Regenstreif A THREAT TO LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King BY Now mE STORY of the Progressive revolt and its impact on the Canadian national party system during the 1920's is well documented and known. Various studies, from the pioneering effort of W. L. Morton1 over a decade ago to the second volume of the Mackenzie King official biography2 which has recently appeared, have dealt intensively with the social and economic bases of the movement, the attitudes of its leaders to the institutions and practices of national politics, and the behaviour of its representatives once they arrived in Ottawa. Particularly in biographical analyses, 3 a great deal of attention has also been given to the response of the established leaders and parties to this disrupting influence. It is clearly accepted that the roots of the subsequent multi-party situation in Canada can be traced directly to a specific strain of thought and action underlying the Progressivism of that era. At another level, however, the abatement of the Pro~ gressive tide and the manner of its dispersal by the end of the twenties form the basis for an important piece of Canadian political lore: it is the conventional wisdom that, in his masterful handling of the Progressives, Mackenzie King knew exactly where he was going and that, at all times, matters were under his complete control, much as if the other actors in the play were mere marionettes with King the manipu lator. His official biographers have demonstrated just how illusory this conception is and there is little to be added to their efforts on this score. -

The Good Fight Marcel Cadieux and Canadian Diplomacy

THE GOOD FIGHT MARCEL CADIEUX AND CANADIAN DIPLOMACY BRENDAN KELLY UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL CONTENTS Foreword / ix Robert Bothwell and John English Preface / xii 1 The Birth of a French Canadian Nationalist, 1915–41 / 3 2 Premières Armes: Ottawa, London, Brussels, 1941–47 / 24 3 The Making of a Diplomat and Cold Warrior, 1947–55 / 55 4 A Versatile Diplomat, 1955–63 / 98 5 Departmental Tensions: Cadieux, Paul Martin Sr., and Canadian Foreign Policy, 1963–68 / 135 6 A Lonely Fight: Countering France and the Establishment of Quebec’s “International Personality,” 1963–67 / 181 7 The National Unity Crisis: Resisting Quebec and France at Home and in la Francophonie, 1967–70 / 228 UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL CONTENTS 8 The Politician and the Civil Servant: Pierre Trudeau, Cadieux, and the DEA, 1968–70 / 260 9 Ambassadorial Woes: Washington, 1970–75 / 296 10 Final Assignments, 1975–81 / 337 Conclusion / 376 Acknowledgments / 380 List of Abbreviations / 382 Notes / 384 Bibliography / 445 Illustration Credits / 461 Index / 463 UBC PRESS ©viii SAMPLE MATERIAL 1 THE BIRTH OF A FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALIST, 1915–41 n an old christening custom that is all but forgotten today, Joseph David Roméo Marcel Cadieux was marked from birth by a traditional IFrench Canadian Catholicism. As a boy, he was named after Saint Joseph. The Hebraic David was the first name of his godfather, his paternal grandfather, a Montreal plasterer. Marcel’s father, Roméo, joined the Royal Mail and married Berthe Patenaude in 1914. She was one of more than a dozen children of Arthur Patenaude, a “gentleman” landowner whose family had deep roots in what had once been the Seigneury of Longueuil, on the south shore of the St. -

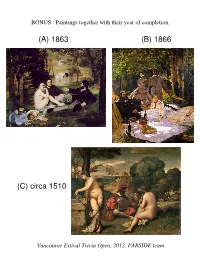

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look. -

The Roots of French Canadian Nationalism and the Quebec Separatist Movement

Copyright 2013, The Concord Review, Inc., all rights reserved THE ROOTS OF FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND THE QUEBEC SEPARATIST MOVEMENT Iris Robbins-Larrivee Abstract Since Canada’s colonial era, relations between its Fran- cophones and its Anglophones have often been fraught with high tension. This tension has for the most part arisen from French discontent with what some deem a history of religious, social, and economic subjugation by the English Canadian majority. At the time of Confederation (1867), the French and the English were of almost-equal population; however, due to English dominance within the political and economic spheres, many settlers were as- similated into the English culture. Over time, the Francophones became isolated in the province of Quebec, creating a densely French mass in the midst of a burgeoning English society—this led to a Francophone passion for a distinct identity and unrelent- ing resistance to English assimilation. The path to separatism was a direct and intuitive one; it allowed French Canadians to assert their cultural identities and divergences from the ways of the Eng- lish majority. A deeper split between French and English values was visible before the country’s industrialization: agriculture, Ca- Iris Robbins-Larrivee is a Senior at the King George Secondary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she wrote this as an independent study for Mr. Bruce Russell in the 2012/2013 academic year. 2 Iris Robbins-Larrivee tholicism, and larger families were marked differences in French communities, which emphasized tradition and antimaterialism. These values were at odds with the more individualist, capitalist leanings of English Canada. -

The Rise and Decline of the Cooperative Commonwealth

THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies B. A. State University of New York at Potsdam, 1987 M. A. State University of New York at Empire State, 2005 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine December 2019 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Nathan Godfried, Professor of History Stephen Miller, Professor of History Howard Cody, Professor Emeritus of Political Science Copyright 2019 Charles A. Deshaies All Rights Reserved ii THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE COOPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH FEDERATION IN ONTARIO AND QUEBEC DURING WORLD WAR II, 1939 – 1945 By Charles A. Deshaies Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Scott See and Dr. Jacques Ferland An Abstract of the Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) December 2019 The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was one of the most influential political parties in Canadian history. Without doubt, from a social welfare perspective, the CCF helped build and develop an extensive social welfare system across Canada. It has been justly credited with being one of the major influences over Canadian social welfare policy during the critical years following the Great Depression. This was especially true of the period of the Second World War when the federal Liberal government of Mackenzie King adroitly borrowed CCF policy planks to remove the harsh edges of capitalism and put Canada on the path to a modern Welfare State. -

“Anglo-Conformity”: Assimilation Policy in Canada, 1890S–1950S1

Jatinder Mann “Anglo-Conformity”: Assimilation Policy in Canada, 1890s–1950s1 Abstract In the late nineteenth century Canada started to receive large waves of non- British migrants for the very first time in its history. These new settlers arrived in a country that saw itself very much as a British society. English-speaking Canadians considered themselves a core part of a worldwide British race. French Canadians, however, were obviously excluded from this ethnic identity. The maintenance of the country as a white society was also an integral part of English-speaking Canada’s national identity. Thus, white non-British migrants were required to assimilate into this English-speaking Canadian or Anglocen- tric society without delay. But in the early 1950s the British identity of English- speaking Canada began to decline ever so slowly. The first steps toward the gradual breakdown of the White Canada policy also occurred at this time. This had a corresponding weakening effect on the assimilation policy adopted toward non-British migrants, which was based on Anglo-conformity. Résumé À la fin du 19e siècle, pour la première fois de son histoire, le Canada commençait à accueillir des vagues importantes d’immigrants non britanni- ques. Ces nouveaux arrivants entraient dans un pays qui se percevait en grande partie comme une société britannique. Les anglophones canadiens se con- sidéraient en effet comme une composante centrale de la « race » britannique mondiale. Les francophones, en revanche, étaient de toute évidence exclus de cette identité ethnique. Par ailleurs, une autre composante essentielle de l’identité nationale canadienne anglophone était la pérennité du pays en tant que société blanche. -

King of Canada Study Guide | Action Infini 2021 2

King of Canada Study Guide Action Infini 2020/2021 Season KING OF CANADA STUDY GUIDE | ACTION INFINI 2021 2 Table of Contents Infinithéâtre’s Mandate ……...………………………………………………………………... 3 Note from the Playwright ……………………………………………………………………... 6 King of Canada and Infinithéâtre Team .……………..……………………………………. 7 William Lyon Mackenzie King (Biography) …………………………………………………. 8 Transcript of a Séance ……………………………………………………………………… 13 Psychologist dives into seances and 'contacting the dead' …………………………….. 17 Canada statue of John A Macdonald toppled by activists in Montreal ………………… 23 The Who’s Who? of King of Canada ……………………………………………..………. 26 Excerpts from King of Canada …………………………………………………………..... 36 Post-Show Discussion……………………………….…………………………………….… 42 Thank You ………………………………………………………………………………….… 43 Sponsors ………………………………………………………………………………….….. 44 2 KING OF CANADA STUDY GUIDE | ACTION INFINI 2021 3 Infinithéâtre’s Mandate REFLECTING AND EXPLORING LIFE IN 21ST CENTURY QUÉBEC (In English) Article written by the AD Emeritus, Guy Sprung Infinithéâtre stages exciting, entertaining, relevant theatre that explores and reflects the issues, challenges and possibilities of contemporary Québec from the perspective of its diverse English-language minority. Our work is driven by the fundamental belief that theatre that speaks to and about the lives, the hopes and the tragedies of its home community has the best possibility of creating an electric connection between stage and audience that is the essence of great theatre. Infinithéâtre is the one theatre in Québec (in French or English!) whose mission is to develop, promote, produce and broker only plays written or adapted by Québec writers and Indigenous writers from within the territory called Canada. We do this, because we believe fundamentally that producing our own writers will generate subject matter and themes relevant to Montréal and Québec and result in the strongest possible engagement and live interaction with our audience. -

The Supremecourt History Of

The SupremeCourt of Canada History of the Institution JAMES G. SNELL and FREDERICK VAUGHAN The Osgoode Society 0 The Osgoode Society 1985 Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-34179 (cloth) Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Snell, James G. The Supreme Court of Canada lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-802@34179 (bound). - ISBN 08020-3418-7 (pbk.) 1. Canada. Supreme Court - History. I. Vaughan, Frederick. 11. Osgoode Society. 111. Title. ~~8244.5661985 347.71'035 C85-398533-1 Picture credits: all pictures are from the Supreme Court photographic collection except the following: Duff - private collection of David R. Williams, Q.c.;Rand - Public Archives of Canada PA@~I; Laskin - Gilbert Studios, Toronto; Dickson - Michael Bedford, Ottawa. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Social Science Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA History of the Institution Unknown and uncelebrated by the public, overshadowed and frequently overruled by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court of Canada before 1949 occupied a rather humble place in Canadian jurisprudence as an intermediate court of appeal. Today its name more accurately reflects its function: it is the court of ultimate appeal and the arbiter of Canada's constitutionalquestions. Appointment to its bench is the highest achieve- ment to which a member of the legal profession can aspire. This history traces the development of the Supreme Court of Canada from its establishment in the earliest days following Confederation, through itsattainment of independence from the Judicial Committeeof the Privy Council in 1949, to the adoption of the Constitution Act, 1982. -

Manuel Observateur (D-6366)

Instruments of direct democracy in Canada and Québec 3rd edition Instruments of direct democracy in Canada and Québec 3rd edition In this document, the masculine form designates both women and men. A copy of this document can be obtained from the Information Centre: By mail: Information centre Le Directeur général des élections du Québec Édifice René-Lévesque 3460, rue de La Pérade Sainte-Foy (Québec) G1X 3Y5 By telephone: Québec City area: (418) 528-0422 Toll-free: 1 888 353-2846 By fax: (418) 643-7291 By e-mail: [email protected] The Internet site of the DGE can also be consulted at: www.dgeq.qc.ca Ce document est disponible en français. The 1st edition of this study was prepared by Charlotte Perreault. The second edition was prepared by France Lavergne. Julien Côté was responsible for updating the 3rd edition. Legal deposit - 2nd quarter 2001 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec National Library of Canada ISBN 2-550-37478-9 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1Instruments of direct democracy ........................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Referendum and plebiscite: definitions ........................................................................................ 3 1.2 Referendums ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Popular initiatives ........................................................................................................................ -

'Atlantic Seat' on the Supreme Court of Canada: an Endangered Species?

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference All Papers Papers 2017 The Atl‘ antic Seat’ on the Supreme Court of Canada: An Endangered Species? Philip Girard Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/all_papers Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Girard, Philip, "The A‘ tlantic Seat’ on the Supreme Court of Canada: An Endangered Species?" (2017). All Papers. 277. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/all_papers/277 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers, Working Papers, Conference Papers at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Papers by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. “The ‘Atlantic Seat’ on the Supreme Court of Canada: An Endangered Species?” Philip Girard* I. Introduction The sigh of relief on the Atlantic coast could be heard all the way to Ottawa on October 17, 2016. On that day, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the nomination of Justice Malcolm Rowe of the Newfoundland and Labrador Court of Appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada seat vacated by Justice Thomas Cromwell. Justice Cromwell’s replacement was to be the first appointed pursuant to a new process put in place by the Trudeau government. When that process was unveiled on August 2, 2016, Trudeau announced that the position would be open to any qualified Canadian lawyer or judge who was functionally bilingual and “representative of the diversity of our great country.” A further clarification stated that “[a]pplications are being accepted from across Canada in order to allow for a selection process that ensures outstanding individuals are considered for appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada,” confirming that Atlantic Canadians did not have a lock on the position.1 People on the east coast generally take most things in stride, but this proposed change created a considerable outcry. -

Canadian Government Policy Towards Titular Honours Fkom Macdondd to Bennett

Questions of Honoar: Canadian Government Policy Towards Titular Honours fkom Macdondd to Bennett by Christopher Pad McCreery A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Caaada September, 1999 Q Christopher Paul McCreery National birary Biblioth&quenationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliagraphiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON KIAON4 OIEawaON K1AON4 Canada Cariada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde melicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheqe nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, preter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format ekctronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni Ia these ai des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &re imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation- Abstract This thesis examines the Canadian government's policy towards British tituiar honours and their bestowal upon residents of Canada, c. 1867-1935. In the following thesis, I will employ primary documents to undertake an original study of the early development of government policy towards titular honours. The evolution and development of the Canadian government's policy will be examined in the context of increasing Canadian autonomy within the British Empire/Commonwealth- The incidents that prompted the development of a Canadian made formal policy will also be discussed. -

BETCHERMAN, Lita-Rose, Ernest Lapointe. Mackenzie King's Great Quebec Lieutenant (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2002)

Document generated on 10/02/2021 7:37 p.m. Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française BETCHERMAN, Lita-Rose, Ernest Lapointe. Mackenzie King’s Great Quebec Lieutenant (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2002), 426 p. John Macfarlane Volume 56, Number 2, Fall 2002 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/007318ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/007318ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Institut d'histoire de l'Amérique française ISSN 0035-2357 (print) 1492-1383 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Macfarlane, J. (2002). Review of [BETCHERMAN, Lita-Rose, Ernest Lapointe. Mackenzie King’s Great Quebec Lieutenant (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2002), 426 p.] Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 56(2), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.7202/007318ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ haf_v56n02.qxd 04/02/03 15:13 Page 235 comptes rendus BETCHERMAN, Lita-Rose, Ernest Lapointe. Mackenzie King’s Great Quebec Lieutenant (Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2002), 426 p. Ce livre fournit une excellente description des événements marquants dans la vie de l’homme «extraordinaire» que fut Ernest Lapointe.