Manuel Observateur (D-6366)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapports Financiers Annuels

FINANCEMENT DES PARTIS POLITIQUES TS TIS POLITIQUES RAPPORTS AR FINANCIERS EXERCICE TERMINÉ LE 31 DÉCEMBRE 2009 TERMINÉ LE 31 DÉCEMBRE 2009 FINANCEMENT DES P EXERCICE RAPPOR FINANCIERS JUIN 2010 Le Directeur général des élections du Québec contribue à la préservation de l'environnement en imprimant les pages blanches de ce document sur du papier contenant 100% de fibres recyclées. 100% © Directeur général des élections du Québec Dépôt légal - 2010 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque nationale du Canada ISBN 978-2-550-58985-3 ISSN 1923-5569 Aux électeurs et électrices du Québec, En vertu de la Loi électorale, j’ai la responsabilité de rendre accessibles au public les rapports financiers annuels. C’est dans cette optique et afin de faciliter la consultation et la compréhension des différentes données que je publie le présent volume sur les rapports financiers des partis politiques provinciaux, de leurs instances, des députés et des candidats indépen- dants autorisés pour l’exercice qui s’est terminé le 31 décembre 2009. Pour obtenir plus de détails concernant ces rapports, vous pouvez vous adresser au Centre de renseignements du Directeur général des élections ou aux représentants officiels des partis politiques. Le directeur général des élections et président de la Commission de la représentation électorale, Marcel Blanchet Juin 2010 Table des matières 1 INFORMATIONS GÉNÉRALES 1.1 Exigences générales de la Loi électorale 7 1.2 Partis politiques autorisés au 31 décembre 2009 et leur représentant officiel au 30 avril -

Memory, Militarism and Citizenship: Tracking the Dominion Institute in Canada's Military-Cultural Memory Network

MEMORY, MILITARISM AND CITIZENSHIP: TRACKING THE DOMINION INSTITUTE IN CANADA'S MILITARY-CULTURAL MEMORY NETWORK by Howard D. Fremeth A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Carleton, University Ottawa, Ontario © 2010 Howard D. Fremeth Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87763-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87763-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Printable PDF Version

CEO Appearance: Supplementary Estimates B 2019-20 Binder Table of Contents Fact Sheets Lead Exercising the Right to Vote Elections Canada’s (EC) Response to Manitoba Storms EEI-OFG Efforts by EC for Indigenous electors PPA-OSE Official languages complaints during the general election (GE) and EC CEO-COS response/proposed solutions Enhanced Services to Jewish Communities RA-LS/EEI- OFG/PPA-OSE Initiatives for target groups PPA-OSE/EEI-OFG Vote on Campus EEI-OFG Regulating Political Entities Activities to educate third parties on the new regime RA-LS/PF Enforcement and Integrity Measures to increase the accuracy of the National Register of Electors (NRoE) EEI-EDMR Social media and disinformation RA-EIO/PPA Election Administration Cost of GE IS-CFO Social media influencer campaign (including response to Written Q-122) PPA-VIC/MRIM Comparison of costs of EC’s and Australia’s voter information campaigns PPA-VIC Security of IT Equipment IS COVID-19 and election preparation IS Background Documentation Lead Placemat – Election Related Stats PPA-P&R Proximity and accessibility of polling stations (improvements for the 43rd GE) EEI Media lines on Voter Qualification/Potential Non-Citizens on the NRoE PPA-MRIM Recent responses to MP Questions (2019) PPA-P&R Registration of Expat Electors-43rd GE EEI Statement on “Enforcement of the third-party regime by the Commissioner of PPA-P&R Canada Elections” Copy of Elections Canada Departmental Plan 2020-21 IS-CFO Copy of Supplementary Estimates IS-CFO *Binder prepared for the appearance of the Chief Electoral Officer before the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs on the Subject of the Supplementary Estimates “B” 2019-20 on March 12, 2020. -

A THREAT to LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King

S. Peter Regenstreif A THREAT TO LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King BY Now mE STORY of the Progressive revolt and its impact on the Canadian national party system during the 1920's is well documented and known. Various studies, from the pioneering effort of W. L. Morton1 over a decade ago to the second volume of the Mackenzie King official biography2 which has recently appeared, have dealt intensively with the social and economic bases of the movement, the attitudes of its leaders to the institutions and practices of national politics, and the behaviour of its representatives once they arrived in Ottawa. Particularly in biographical analyses, 3 a great deal of attention has also been given to the response of the established leaders and parties to this disrupting influence. It is clearly accepted that the roots of the subsequent multi-party situation in Canada can be traced directly to a specific strain of thought and action underlying the Progressivism of that era. At another level, however, the abatement of the Pro~ gressive tide and the manner of its dispersal by the end of the twenties form the basis for an important piece of Canadian political lore: it is the conventional wisdom that, in his masterful handling of the Progressives, Mackenzie King knew exactly where he was going and that, at all times, matters were under his complete control, much as if the other actors in the play were mere marionettes with King the manipu lator. His official biographers have demonstrated just how illusory this conception is and there is little to be added to their efforts on this score. -

Electoral Bias in Quebec Since 1936

Canadian Political Science Review 4(1) March 2010 Electoral Bias in Quebec Since 1936 Alan Siaroff (University of Lethbridge) * Abstract In the period since 1936, Quebec has gone through two eras of party politics, the first between the Liberals and the Union Nationale, the second and ongoing era between the Liberals and the Parti Québécois. This study examines elections in Quebec in terms of all relevant types of electoral bias. In both eras the overall electoral bias has clearly been against the Liberal Party. The nature of this bias has changed however. Malapportionment was crucial through 1970 and of minimal importance since the 1972 redistribution. In contrast gerrymandering, ultimately involving an ‘equivalent to gerrymandering effect’ due to the geographic nature of Liberal core support, has been not only a permanent phenomenon but indeed since 1972 the dominant effect. The one election where both gerrymandering and the overall bias were pro-Liberal — 1989 — is shown to be the ‘exception that proves the rule’. Finally, the erratic extent of electoral bias in the past four decades is shown to arise from very uneven patterns of swing in Quebec. Introduction In common with other jurisdictions using the single-member plurality electoral system, elections results in the province of Quebec tend to be disproportionate. This can be seen in Table 1, which provides some summary measures on elections since 1936 — the time period of this analysis. Average disproportionality over this period has been quite high at 20.19 percent. This has almost entirely been in favour of the winning party, with the average seat bias of the largest party being 19.65 percent. -

The Good Fight Marcel Cadieux and Canadian Diplomacy

THE GOOD FIGHT MARCEL CADIEUX AND CANADIAN DIPLOMACY BRENDAN KELLY UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL CONTENTS Foreword / ix Robert Bothwell and John English Preface / xii 1 The Birth of a French Canadian Nationalist, 1915–41 / 3 2 Premières Armes: Ottawa, London, Brussels, 1941–47 / 24 3 The Making of a Diplomat and Cold Warrior, 1947–55 / 55 4 A Versatile Diplomat, 1955–63 / 98 5 Departmental Tensions: Cadieux, Paul Martin Sr., and Canadian Foreign Policy, 1963–68 / 135 6 A Lonely Fight: Countering France and the Establishment of Quebec’s “International Personality,” 1963–67 / 181 7 The National Unity Crisis: Resisting Quebec and France at Home and in la Francophonie, 1967–70 / 228 UBC PRESS © SAMPLE MATERIAL CONTENTS 8 The Politician and the Civil Servant: Pierre Trudeau, Cadieux, and the DEA, 1968–70 / 260 9 Ambassadorial Woes: Washington, 1970–75 / 296 10 Final Assignments, 1975–81 / 337 Conclusion / 376 Acknowledgments / 380 List of Abbreviations / 382 Notes / 384 Bibliography / 445 Illustration Credits / 461 Index / 463 UBC PRESS ©viii SAMPLE MATERIAL 1 THE BIRTH OF A FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALIST, 1915–41 n an old christening custom that is all but forgotten today, Joseph David Roméo Marcel Cadieux was marked from birth by a traditional IFrench Canadian Catholicism. As a boy, he was named after Saint Joseph. The Hebraic David was the first name of his godfather, his paternal grandfather, a Montreal plasterer. Marcel’s father, Roméo, joined the Royal Mail and married Berthe Patenaude in 1914. She was one of more than a dozen children of Arthur Patenaude, a “gentleman” landowner whose family had deep roots in what had once been the Seigneury of Longueuil, on the south shore of the St. -

T Savoir Tout Savoir Sur Lequébec Sur Lequébec

Tout savoir Tout savoir sur leQuébec sur leQuébec Voici un guide pratique qui renferme tout ce que l’on est censé savoir sur le Québec… mais qu’on a tendance à oublier! Explication des armoiries, symbolique du drapeau, origine de la devise du Québec, emblèmes offi ciels, principales dates historiques… Tout savoir sur le Québec est un recueil à la fois instructif et ludique. Un véritable «condensé du Québec» d’une grande valeur informative, facile à consulter, et qui pourra servir aussi bien d’aide-mémoire pour savoir sur le Québec Tout tous que de livret éducatif pour les jeunes, ou de guide de référence pour les nouveaux arrivants. Vous trouverez dans ce guide • De nombreux textes concis sur des thèmes aussi variés que la gastronomie, les Amérindiens, l’architecture, la géographie, les grandes réalisations québécoises... • Des questions quiz qui ajoutent une dimension interactive tout en permettant d’aborder encore davantage de sujets. • De nombreux encadrés qui mettent en lumière de façon amusante d’autres facettes méconnues du Québec. ISBN: 9782894648780 12,95 $ www.guidesulysse.com 9,99 € TTC en France Le plaisir de mieux voyager Tout savoir sur leQuébec Le plaisir de mieux voyager Recherche et rédaction Illustrateur Pierre Daveluy Pascal Biet Jean-Hugues Robert Collaboration Photographies Pierre Ledoux p 11 © Shutterstock.com/Bruce Amos; p 12 © Dreamstime.com/Andrzej Fryda; p 23 Éditeur et directeur de production © Dreamstime.com/Lauren Jones, Mike Rogal, Olivier Gougeon Reinhard Tiburzy; p 24 © Dreamstime.com/ André Nantel, Graça Victoria; p 38 © Dreams- Correcteur time.com/Mary Lane; p 45 © Dreamstime. Pierre Daveluy com/Marieve Bouchard; p 55 © Dreamstime. -

FINAL REPORT and RECOMMENDATIONS a Review Of

COMPLIANCE REVIEW: FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS A Review of Compliance with Election Day Registration and Voting Process Rules By Harry Neufeld, Reviewer Includes the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada’s Response TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................5 COMPLIANCE REVIEW CONTEXT ........................................................................................9 Ontario Superior Court Decision ........................................................................... 9 Supreme Court of Canada Decision .................................................................... 10 Public Trust at Risk .............................................................................................. 10 The Compliance Review ...................................................................................... 11 Information Gathering .................................................................................... 11 Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................... 12 Interim Report ................................................................................................ 13 Final Report and Recommendations .............................................................. 13 CAUSES OF NON-COMPLIANCE ....................................................................................... 14 Complexity ......................................................................................................... -

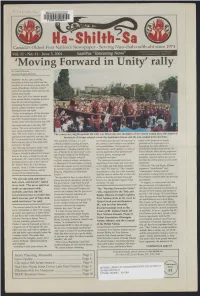

'Moving Forward in Unity' Rally

1 LIBRARY AND CANADA NS,OR.NA,- Bibliother ie et Canada 111,31181151,21611611611 IIII 3 3286 5426465 3 O Na- Shilth -Sa Canada's Oldest First Nation's Newspaper - Serving Nuu -chah- nulth -aht since 1974 Canadian Publications Mail Product Vol. 31 - No. 11 - June 3, 2004 haaitsa "Interesting News" Sales Agreement No. 40047776 'Moving Forward in Unity' rally By David Wiwchar, Southern Region Reporter Victoria - As the canoe carrying Hesquiaht Ha'wiih was lifted onto the shoulders of two -dozen young men, the ' s r . , , ' sound of hundreds of drums echoed '737-34.-'.1,_^1 - across the legislature lawns and the sun - . ,# ` ._« soaked inner harbor. ...va ti, More than 2000 First Nations people =;`" . ' .p'. from around British Columbia marched + J -l .' .-3..i 1 upon the provincial legislature, .. -. i demanding Premier Gordon Campbell a..4 and his cabinet ministers recognize r' Aboriginal title and rights. / "Today were going to tell the province .a who the real owners of this land are," . said NTC Northern Region Co -chair , a. Little, who joined more than 200 s Archie 16:E ' " 5r -aht at the May 20th IY} i ! , Nuu -chah- nulth protest. "We own our land and water lock, stock, and barrel," added Jerry a Jack. "We never sold it or made an The canoe carrying Hesquiaht Ha'wiih was lifted onto the shoulders of two -dozen young men, the sound of agreement with anybody, and they [the hundreds of drums echoed across the legislature lawns and the sun -soaked inner harbour. BC Government] have to realize they Title and Rights Alliance is a new government and industry infringement of spoke to the hundreds of people don't own any part of Nuu -chah -nulth collective initiative among all major the resources that belong to our children gathered on the legislature lawn territories," he said. -

Electoral Systems and Electoral Reform in Canada and Elsewhere: an Overview

Electoral Systems and Electoral Reform in Canada and Elsewhere: An Overview Publication No. 2016-06-E 11 January 2016 Revised 23June 2016 Andre Barnes Dara Lithwick Erin Virgint Legal and Social Affairs Division Parliamentary Information and Research Service Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. © Library of Parliament, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 Electoral Systems and Electoral Reform in Canada and Elsewhere: An Overview (Background Paper) Publication No. 2016-06-E Ce document est également publié en français. CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 2 CANADA’S FEDERAL ELECTORAL SYSTEM ........................................................ 1 2.1 Canada’s “First-Past-the-Post” Electoral System .................................................. 1 2.2 Legal Basis ............................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Advantages and Disadvantages of the Status Quo ............................................... 2 2.4 Voter Turnout ........................................................................................................ -

COMPOSITION RÉCENTE DU CORPS POLITIQUE 895 Ministre

COMPOSITION RÉCENTE DU CORPS POLITIQUE 895 Ministre délégué à l'Aménagement et au Développement Ministre de l'Industrie et du Commerce, l'hon. Frank S. régional et président du Comité ministériel permanent de Miller l'aménagement et du développement régional, l'hon. Ministre de l'Agriculture et de l'Alimentation, l'hon. François Gendron Dennis R. Timbrell Ministre des Relations internationales et ministre du Ministre de l'Éducation et ministre des Collèges et des Commerce extérieur, l'hon. Bernard Landry Universités, l'hon. Bette Stephenson, M.D. Ministre de la Main-d'oeuvre et de la Sécurité du revenu Procureur général, l'hon. Roy McMurtry, CR. et vice-présidente du Conseil du Trésor, l'hon. Pauline Marois Ministre de la Santé, l'hon. Keith C. Norton, CR. Ministre de l'Énergie et des Ressources, l'hon. Yves Ministre des Services sociaux et communautaires, l'hon. Duhaime Frank Drea Ministre délégué aux Relations avec les citoyens, l'hon. Trésorier provincial et ministre de l'Économie, l'hon. Denis Lazure Larry Grossman, CR. Ministre des Transports, l'hon. Jacques Léonard Président du conseil d'administration du Cabinet et président du Cabinet, l'hon. George McCague Ministre de l'Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l'Alimentation, l'hon. Jean Garon Ministre du Tourisme et des Loisirs, l'hon. Reuben Baetz Ministre de l'Habitation et de la Protection du Ministre de la Consommafion et du Commerce, l'hon. consommateur, l'hon. Guy Tardif Robert G. Elgie, M.D. Ministre des Affaires culturelles, l'hon. Clément Richard Secrétaire provincial à la Justice, l'hon. -

The Electoral Participation of Persons with Special Needs

Working Paper Series on Electoral Participation and Outreach Practices The Electoral Participation of Persons with Special Needs Michael J. Prince www.elections.ca Working Paper Series on Electoral Participation and Outreach Practices The Electoral Participation of Aboriginal People by Kiera L. Ladner and Michael McCrossan The Electoral Participation of Ethnocultural Communities by Livianna Tossutti The Electoral Participation of Persons with Special Needs by Michael J. Prince The Electoral Participation of Young Canadians by Paul Howe For information, please contact: Public Enquiries Unit Elections Canada 257 Slater Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0M6 Tel.: 1-800-463-6868 Fax: 1-888-524-1444 (toll-free) TTY: 1-800-361-8935 www.elections.ca Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Prince, Michael John, 1952– The electoral participation of persons with special needs / Michael J. Prince. Text in English and French on inverted pages. Title on added t.p.: La participation électorale des personnes ayant des besoins spéciaux. Includes bibliographical references: pp. 41–52 ISBN 978-0-662-69824-1 Cat. no.: SE3-70/2007 1. People with disabilities — Suffrage — Canada. 2. Homeless persons — Suffrage — Canada. 3. Illiterate persons — Suffrage — Canada. 4. Suffrage — Canada. I. Elections Canada. II. Title: La participation électorale des personnes ayant des besoins spéciaux. JL191.P74 2007 324.6'20870971 C2007-980108-0E © Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, 2007 All rights reserved Printed and bound in Canada EC 91010 Table of Contents Foreword.........................................................................................................................................5