Contradictions of Economic Growth in the Neoliberal Era, Revised Version May 2007 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy: Classicals, post-Keynesians and the New Keynesian Consensus Peter Kriesler and Marc Lavoie1 Abstract The paper looks at the adjustment process towards long run equilibrium within Marxian models, defined in terms of normal rates of capacity utilization. The model is reduced to three essential equations: an IS equation, a Phillips curve equation and an central bank reaction function. It is shown that long run convergence depends on the specific inflation (Phillips curve) equation, and on the central bank setting a zero inflationary target. When these conditions are relaxed, the results are shown to accord more closely with post-Keynesian results. The Marxian model is then contrasted with New Consensus models, which only varies in its inflation/Phillips curve equation. Post-Keynesian criticisms of both the IS and the Phillips curve equation are considered, and suggestions for a post-Keynesian alternative are made. Keywords: monetary policy, central bank, inflation, capacity utilization, post-Keynesian, New- Keynesian JEL classification: E12, E40, E52, E58 In an extremely interesting paper, Duménil and Lévy (Duménil and Lévy 1999) explore the adjustment mechanism of an economy towards a long run equilibrium with capacity utilization at normal levels − a fully adjusted position as the Sraffians would call it, or a classical long-term equilibrium as Duménil and Lévy have it. Short run equilibrium within their model is of the Keynes/Kalecki type, with variability in levels of capacity utilization. One distinctive feature of their model is that it is not the forces of competition which push the economy to a fully adjusted position, but rather aspects of the macro economy coupled with the behaviour of the central bank. -

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

1 SECTION Gross Domestic Product ross domestic product (GDP) is a measure of a country’s economic output. GDP per capita and GDP Gper employed person are related indicators that provide a general picture of a country’s well-being. GDP per capita is an indicator of overall wealth in a country, and GDP per employed person is a general indicator of productivity. 8 CHARTING INTERNATIONAL LABOR COMPARISONS | SEPTEMBER 2012 U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS | www.bls.gov Gross domestic product, selected countries, in U.S. dollars, 2010 United States China Japan CHART India 1.1 Germany Gross domestic United Kingdom France product (GDP) Brazil was more Italy than 14 trillion Mexico dollars in the Spain South Korea United States Canada and exceeded Australia 4 trillion Poland dollars in only Netherlands Argentina three other Belgium countries: Sweden China, Japan, Philippines and India. Switzerland Austria In addition to China Greece Singapore and India, other large Czech Republic emerging economies, Norway such as Brazil and Portugal Mexico, were among the Israel 10 largest countries in Denmark terms of GDP. Hungary Finland The GDP of the United Ireland States was roughly 5 New Zealand times larger than that of Slovakia Germany, 10 times larger Estonia than that of South Korea, 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Trillions of 2010 U.S. dollars and 40 times larger than that of the Philippines. NOTE: GDP is converted to U.S. dollars using purchasing power parities (PPP). See section notes. SOURCES: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and The World Bank. -

Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle

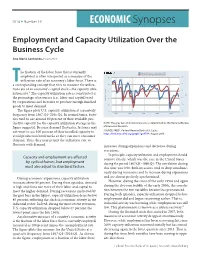

2016 n Number 19 ECONOMIC Synopses Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle Ana Maria Santacreu, Economist he fraction of the labor force that is currently Capacity Utilization: Total Industry (left) 100-Civilian Unemployment Rate (right) 98 employed is often interpreted as a measure of the 90 utilization rate of an economy’s labor force. There is 96 T 85 a corresponding concept that tries to measure the utiliza- tion rate of an economy’s capital stock—the capacity utili- 94 80 zation rate.1 The capacity utilization rate is constructed as 100-% 92 the percentage of resources (i.e., labor and capital) used 75 Percent of Capacity by corporations and factories to produce enough finished 90 goods to meet demand. 70 88 The figure plots U.S. capacity utilization at a quarterly 65 frequency from 1967:Q1–2016:Q1. In normal times, facto- 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 ries tend to use around 80 percent of their available pro- fred.stlouisfed.org myf.red/g/6ZXZ ductive capacity (as the capacity utilization average in the NOTE: The gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau figure suggests). Because demand fluctuates, factories may of Economic Research. SOURCE: FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; not want to use 100 percent of their installed capacity to https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=6TA4; August 2016. avoid production bottlenecks so they can meet consumer demand. Thus, they may permit the utilization rate to fluctuate with demand. increases during expansions and decreases during recessions. In principle, capacity utilization and employment should Capacity and employment are affected comove closely, which was the case in the United States by cyclical factors, but employment during the period 1967:Q1–1990:Q1. -

A Better Measure of Economic Growth: Gross Domestic Output (Gdo)

COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS ISSUE BRIEF JULY 2015 A BETTER MEASURE OF ECONOMIC GROWTH: GROSS DOMESTIC OUTPUT (GDO) The growth of total economic output affects our assessment of current well-being as well as decisions about the future. Measuring the strength of the economy, however, can be difficult as it depends on surveys and administrative source data that are necessarily imperfect and incomplete. The total output of the economy can be measured in two distinct ways—Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which adds consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports; and Gross Domestic Income (GDI), which adds labor compensation, business profits, and other sources of income. In theory these two measures of output should be identical; however, they differ in practice because of measurement error. With today’s annual revision, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) began publishing a new measure of U.S. output—the “average of GDP and GDI”—which the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) will refer to as Gross Domestic Output (GDO).1 This issue brief describes GDO, reviews its recent trends, and explains why it can be a more accurate measure of current economic growth and a better predictor of future economic growth than either GDP or GDI alone. What is Gross Domestic Output (GDO)? The first estimate of quarterly GDP is released nearly a month after each quarter’s end. Owing to data lags, GDI What we are calling “GDO” is the average of two existing is generally first released nearly two months after series, the headline Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and quarter’s end, along with the second estimate of GDP.2 its lesser-known counterpart, Gross Domestic Income As a result, with today’s advance GDP release, GDI and (GDI). -

Imbalance Game 2.0: a Tale of Two Productivities

NEW THINKING Imbalance Game 2.0: A Tale of Two Productivities Michael Craig, CFA Vice President & Director Haining Zha, CFA Vice President September 2017 Almost nine years after the financial crisis, the global economy remains mired in low growth. Low productivity growth is certainly a key contributing factor, but our research shows that current productivity measures don’t tell the whole story. In this article, we propose a fundamental change to how people should examine productivity: we believe the supply and demand sides should be viewed separately to obtain more robust insights. Taking this approach allows us to differentiate supply-side progress from demand-side malaise and shows that the economy may be more promising than commonly thought. In addition, it highlights large supply-side divergences within and across different sectors of the economy, which are not reflected in the aggregate productivity measure – potentially leading to a distorted economic picture. Viewing productivity through this new lens, we believe that: • Nominal economic growth will remain low • Inflation will remain subdued • Interest rates will stay lower for longer • Technology-driven progress and persistent supply-side divergence will create investment risks and opportunities in equity markets In the investment world, economic growth is a big deal. We believe investment returns across asset classes can ultimately be traced back to one source: economic growth. Occasionally, asset prices can deviate from fundamentals, but over the long term, the relationship between returns and growth is very strong. That’s why it is critical to have a better understanding of the low growth phenomenon and key contributing factors, such as productivity. -

Income, Expenditures, Poverty, and Wealth

Section 13 Income, Expenditures, Poverty, and Wealth This section presents data on gross periodically conducts the Survey of domestic product (GDP), gross national Consumer Finances, which presents finan- product (GNP), national and personal cial information on family assets and net income, saving and investment, money worth. The most recent survey is available income, poverty, and national and at <http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs personal wealth. The data on income and /oss/oss2/scfindex.html>. Detailed infor- expenditures measure two aspects of the mation on personal wealth is published U.S. economy. One aspect relates to the periodically by the Internal Revenue National Income and Product Accounts Service (IRS) in SOI Bulletin. (NIPA), a summation reflecting the entire complex of the nation’s economic income National income and product— and output and the interaction of its GDP is the total output of goods and major components; the other relates to services produced by labor and prop- the distribution of money income to erty located in the United States, valued families and individuals or consumer at market prices. GDP can be viewed in income. terms of the expenditure categories that comprise its major components: The primary source for data on GDP, GNP, personal consumption expenditures, national and personal income, gross gross private domestic investment, net saving and investment, and fixed assets exports of goods and services, and gov- and consumer durables is the Survey of ernment consumption expenditures and Current Business, published monthly by gross investment. The goods and services the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). included are largely those bought for final A comprehensive revision to the NIPA use (excluding illegal transactions) in the was released beginning in July 2009. -

Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues

Working Paper No. 952 Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues by Michalis Nikiforos* Levy Economics Institute of Bard College April 2020 * For useful comments, the author would like to thank participants at the 45th annual Eastern Economic Association conference in New York and those at the 23rd Forum for Microeconomics and Macroeconomics conference in Berlin. The usual disclaimer applies The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2020 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT This paper discusses some issues related to the triangle between capital accumulation, distribution, and capacity utilization. First, it explains why utilization is a crucial variable for the various theories of growth and distribution—more precisely, with regards to their ability to combine an autonomous role for demand (along Keynesian lines) and an institutionally determined distribution (along classical lines). Second, it responds to some recent criticism by Girardi and Pariboni (2019). I explain that their interpretation of the model in Nikiforos (2013) is misguided, and that the results of the model can be extended to the case of a monopolist. -

3. GDP Per Capita

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT (GDP) 3. GDP per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is a core indicator needed in interpretation, for example Luxembourg and, to a of economic performance and commonly used as a broad lesser extent, Switzerland have a relatively large number of measure of average living standards or economic well- frontier workers. Such workers contribute to GDP but are being; despite some recognised shortcomings. excluded from the population figures, which is one of the For example average GDP per capita gives no indication of reasons why cross-country comparisons of income per how GDP is distributed between citizens. Average GDP per capita based on gross or net national income (GDI and NNI) capita may rise for example but more people may be worse are often preferred, see second chapter on Income. (See also off if income inequalities also increase. “Reader’s guide”, relating to PPP based comparisons.) Equally, in some countries (see Comparability), there may be a significant number of non-resident border or seasonal Source workers or indeed inflows and outflows of property income • OECD (2012), National Accounts of OECD Countries, OECD and both phenomena imply that the value of production Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2221433x. differs from the income of residents, thereby over or under- stating their living standards. Online database A full discussion of these issues can be found in the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi report (see “Further reading”). • OECD (2012), “Aggregate National Accounts: Gross domestic product”, OECD National Accounts Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00001-en. Definition Further reading The definition for GDP is described in Section 1 and • Lequiller, F. -

Hungary (24 June 2021)

Coronavirus response in 2021: building back better Update on Hungary (24 June 2021) Covid-19 policy response EBRD assessment of transition qualities (ATQs), 20201 • The authorities implemented a major policy response in 2020, amounting to around 18 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), focused on income support for vulnerable individuals, liquidity Competitive Inclusive support for businesses and budgetary support for the health sector. Well-governed Resilient • Covid-19-related fiscal measures in 2021 are projected at 12 per cent of GDP, with continued spending on pandemic protection and support for the economic recovery, including a value-added Green Integrated tax cuts on new housing, more money for the pandemic control fund and a wage hike for doctors. • Substantial European Union (EU) funds will help boost the short-term recovery. Hungary is 0 2 4 6 8 10 0 2 4 6 8 10 expected to receive about €41 billion in total from the bloc’s regular multiannual financial Hungary EBRD Advanced comparators framework (MFF) and an extraordinary Covid-19 recovery fund. Building back better: key ongoing initiatives Macroeconomic indicators (%) The government is adding HUF 30 billion (around €86 million) to its existing Competitive competitiveness programme for companies that maintain employment at current levels. 2018 2019 2020 Short-term indicators The government is supporting investments in residential solar power systems and the Green electrification of residential heating systems. EBRD GDP growth forecast (June 2021) GDP growth 5.4 4.6 -5.0 Water management reform is set to boost Hungary's resilience to climate change and to 2021: 5.5%; 2022: 4.8% Resilient Annual inflation (end-year) -0.4 0.3 0.3 improve the conditions of drought-prone ecosystems. -

The Great Depression As a Historical Problem

Upjohn Institute Press The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego Chapter 3 (pp. 63-94) in: The Economics of the Great Depression Mark Wheeler, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1998 DOI: 10.17848/9780585322049.ch3 Copyright ©1998. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. 3 The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego It is now over a half-century since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the most severe and protracted economic crisis in American his tory. To this day, there exists no general agreement about its causes, although there tends to be a consensus about its consequences. Those who at the time argued that the Depression was symptomatic of a pro found weakness in the mechanisms of capitalism were only briefly heard. After World War II, their views appeared hysterical and exag gerated, as the industrialized nations (the United States most prominent among them) sustained dramatic rates of growth and as the economics profession became increasingly preoccupied with the development of Keynesian theory and the management of the mixed economy. As a consequence, the economic slump of the inter-war period came to be viewed as a policy problem rather than as an outgrowth of fundamental tendencies in capitalist development. Within that new context, a debate persisted for a few years, but it too eventually subsided. The presump tion was that the Great Depression could never be repeated owing to the increasing sophistication of economic analysis and policy formula tion. -

"The Macroeconomics of Happiness." (Pdf)

The Macroeconomics of Happiness Author(s): Rafael Di Tella, Robert J. MacCulloch and Andrew J. Oswald Source: The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Nov., 2003), pp. 809-827 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3211807 Accessed: 25-11-2019 16:44 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Review of Economics and Statistics This content downloaded from 206.253.207.235 on Mon, 25 Nov 2019 16:44:09 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE MACROECONOMICS OF HAPPINESS Rafael Di Tella, Robert J. MacCulloch, and Andrew J. Oswald* Abstract-We show that macroeconomic movements have omitted strong from effects economists' standard calculations of the cost on the happiness of nations. First, we find that there are clear microeco- of cyclical downturns. nomic patterns in the psychological well-being levels of a quarter of a million randomly sampled Europeans and Americans from In thespite 1970s of a longto tradition studying aggregate economic the 1990s. Happiness equations are monotonically increasing fluctuations, in income, there is disagreement among economists about and have similar structure in different countries. -

National Income Per Capita

PRODUCTION AND INCOME • INCOME, SAVINGS AND INVESTMENTS NATIONALPRODUCTIONIncome, savings AND and INCOME investments INCOME PER CAPITA While per capita gross domestic product is the indicator Depreciation, which is deducted from GNI to obtain NNI, is most commonly used to compare living standards across the decline in the market value of fixed capital assets – countries, two other measures are preferred by many dwellings, buildings, machinery, transport equipment such analysts. These are per capita gross national income (GNI) as physical infrastructure, software, etc. – through wear and and net national income (NNI). tear and obsolescence. Definition Comparability GNI is defined as GDP plus net receipts from abroad of Both income measures are compiled according to the wages and salaries and property income. definitions of the 1993 System of National Accounts. There are, Wages and salaries from abroad are those that are earned by however, practical difficulties in measuring international residents, i.e. by persons who essentially live and consume flows of wages and salaries and property income and inside the economic territory of a country but work abroad depreciation. Because of these difficulties, GDP per capita is (this happens in border areas on a regular basis) or by the most widely used indicator of income despite being persons that live and work abroad for only short periods theoretically inferior to either GNI or NNI. (seasonal workers). Guest-workers and other migrant Note that data for Australian and New Zealand refer to fiscal workers who live abroad for one year or more are considered years. to be resident in the country where they are working.