Measuring Capacity Utilization in OECD Countries: a Cointegration Method

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy

Capacity Utilization, Inflation and Monetary Policy: Classicals, post-Keynesians and the New Keynesian Consensus Peter Kriesler and Marc Lavoie1 Abstract The paper looks at the adjustment process towards long run equilibrium within Marxian models, defined in terms of normal rates of capacity utilization. The model is reduced to three essential equations: an IS equation, a Phillips curve equation and an central bank reaction function. It is shown that long run convergence depends on the specific inflation (Phillips curve) equation, and on the central bank setting a zero inflationary target. When these conditions are relaxed, the results are shown to accord more closely with post-Keynesian results. The Marxian model is then contrasted with New Consensus models, which only varies in its inflation/Phillips curve equation. Post-Keynesian criticisms of both the IS and the Phillips curve equation are considered, and suggestions for a post-Keynesian alternative are made. Keywords: monetary policy, central bank, inflation, capacity utilization, post-Keynesian, New- Keynesian JEL classification: E12, E40, E52, E58 In an extremely interesting paper, Duménil and Lévy (Duménil and Lévy 1999) explore the adjustment mechanism of an economy towards a long run equilibrium with capacity utilization at normal levels − a fully adjusted position as the Sraffians would call it, or a classical long-term equilibrium as Duménil and Lévy have it. Short run equilibrium within their model is of the Keynes/Kalecki type, with variability in levels of capacity utilization. One distinctive feature of their model is that it is not the forces of competition which push the economy to a fully adjusted position, but rather aspects of the macro economy coupled with the behaviour of the central bank. -

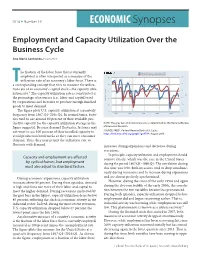

Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle

2016 n Number 19 ECONOMIC Synopses Employment and Capacity Utilization Over the Business Cycle Ana Maria Santacreu, Economist he fraction of the labor force that is currently Capacity Utilization: Total Industry (left) 100-Civilian Unemployment Rate (right) 98 employed is often interpreted as a measure of the 90 utilization rate of an economy’s labor force. There is 96 T 85 a corresponding concept that tries to measure the utiliza- tion rate of an economy’s capital stock—the capacity utili- 94 80 zation rate.1 The capacity utilization rate is constructed as 100-% 92 the percentage of resources (i.e., labor and capital) used 75 Percent of Capacity by corporations and factories to produce enough finished 90 goods to meet demand. 70 88 The figure plots U.S. capacity utilization at a quarterly 65 frequency from 1967:Q1–2016:Q1. In normal times, facto- 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 ries tend to use around 80 percent of their available pro- fred.stlouisfed.org myf.red/g/6ZXZ ductive capacity (as the capacity utilization average in the NOTE: The gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau figure suggests). Because demand fluctuates, factories may of Economic Research. SOURCE: FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; not want to use 100 percent of their installed capacity to https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=6TA4; August 2016. avoid production bottlenecks so they can meet consumer demand. Thus, they may permit the utilization rate to fluctuate with demand. increases during expansions and decreases during recessions. In principle, capacity utilization and employment should Capacity and employment are affected comove closely, which was the case in the United States by cyclical factors, but employment during the period 1967:Q1–1990:Q1. -

Imbalance Game 2.0: a Tale of Two Productivities

NEW THINKING Imbalance Game 2.0: A Tale of Two Productivities Michael Craig, CFA Vice President & Director Haining Zha, CFA Vice President September 2017 Almost nine years after the financial crisis, the global economy remains mired in low growth. Low productivity growth is certainly a key contributing factor, but our research shows that current productivity measures don’t tell the whole story. In this article, we propose a fundamental change to how people should examine productivity: we believe the supply and demand sides should be viewed separately to obtain more robust insights. Taking this approach allows us to differentiate supply-side progress from demand-side malaise and shows that the economy may be more promising than commonly thought. In addition, it highlights large supply-side divergences within and across different sectors of the economy, which are not reflected in the aggregate productivity measure – potentially leading to a distorted economic picture. Viewing productivity through this new lens, we believe that: • Nominal economic growth will remain low • Inflation will remain subdued • Interest rates will stay lower for longer • Technology-driven progress and persistent supply-side divergence will create investment risks and opportunities in equity markets In the investment world, economic growth is a big deal. We believe investment returns across asset classes can ultimately be traced back to one source: economic growth. Occasionally, asset prices can deviate from fundamentals, but over the long term, the relationship between returns and growth is very strong. That’s why it is critical to have a better understanding of the low growth phenomenon and key contributing factors, such as productivity. -

Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues

Working Paper No. 952 Notes on the Accumulation and Utilization of Capital: Some Theoretical Issues by Michalis Nikiforos* Levy Economics Institute of Bard College April 2020 * For useful comments, the author would like to thank participants at the 45th annual Eastern Economic Association conference in New York and those at the 23rd Forum for Microeconomics and Macroeconomics conference in Berlin. The usual disclaimer applies The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2020 All rights reserved ISSN 1547-366X ABSTRACT This paper discusses some issues related to the triangle between capital accumulation, distribution, and capacity utilization. First, it explains why utilization is a crucial variable for the various theories of growth and distribution—more precisely, with regards to their ability to combine an autonomous role for demand (along Keynesian lines) and an institutionally determined distribution (along classical lines). Second, it responds to some recent criticism by Girardi and Pariboni (2019). I explain that their interpretation of the model in Nikiforos (2013) is misguided, and that the results of the model can be extended to the case of a monopolist. -

The Great Depression As a Historical Problem

Upjohn Institute Press The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego Chapter 3 (pp. 63-94) in: The Economics of the Great Depression Mark Wheeler, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1998 DOI: 10.17848/9780585322049.ch3 Copyright ©1998. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. All rights reserved. 3 The Great Depression as a Historical Problem Michael A. Bernstein University of California, San Diego It is now over a half-century since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the most severe and protracted economic crisis in American his tory. To this day, there exists no general agreement about its causes, although there tends to be a consensus about its consequences. Those who at the time argued that the Depression was symptomatic of a pro found weakness in the mechanisms of capitalism were only briefly heard. After World War II, their views appeared hysterical and exag gerated, as the industrialized nations (the United States most prominent among them) sustained dramatic rates of growth and as the economics profession became increasingly preoccupied with the development of Keynesian theory and the management of the mixed economy. As a consequence, the economic slump of the inter-war period came to be viewed as a policy problem rather than as an outgrowth of fundamental tendencies in capitalist development. Within that new context, a debate persisted for a few years, but it too eventually subsided. The presump tion was that the Great Depression could never be repeated owing to the increasing sophistication of economic analysis and policy formula tion. -

Capacity and Capacity Utilization in Fishing Industries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by College of William & Mary: W&M Publish W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Books and Book Chapters Virginia Institute of Marine Science 2003 Capacity And Capacity Utilization In Fishing Industries James E. Kirkley Dale Squires Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Extracted from : Pascoe, S.; Gréboval, D. (eds.) Measuring capacity in fisheries. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. No. 445. Rome, FAO. 2003. 314p. http://www.fao.org/3/Y4849E/y4849e00.htm http://www.fao.org/3/Y4849E/y4849e04.htm#bm04 CAPACITY AND CAPACITY UTILIZATION IN FISHING INDUSTRIES – James E. Kirkley[24] and Dale Squires[25] Abstract: The definition and measurement of capacity in fishing and other natural resource industries possess unique problems because of the stock-flow production technology, in which inputs are applied to the natural resource stock to produce a flow of output. In addition, there are often multiple resource stocks, corresponding to different species, with a mobile stock of capital that can exploit one or more of these stocks. In turn, this leads to three unique issues: (1) multiple stocks of capital and the resource; (2) that of aggregation or how to define the industry and resource stocks to consider; and (3), that of latent capacity or how to include stocks of capital that are currently inactive or exploit the resource stock only at low levels of variable input utilization. This paper presents appropriate definitions of capacity and methods for measuring capacity in fishing industries taking into consideration these issues. -

Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Aloi, Marta; Dixon, Huw D. Working Paper Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy CESifo Working Paper, No. 716 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Aloi, Marta; Dixon, Huw D. (2002) : Entry Dynamics, Capacity Utilisation and Productivity in a Dynamic Open Economy, CESifo Working Paper, No. 716, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/75945 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu A joint Initiative of Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and Ifo Institute for Economic Research Working Papers ENTRY DYNAMICS, CAPACITY UTILISATION AND PRODUCTIVITY IN A DYNAMIC OPEN ECONOMY* Marta Aloi Huw Dixon CESifo Working Paper No. -

The Changing Dynamics of Short-Run Output Adjustment Korkut Alp Ertürk

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES The changing dynamics of short-run output adjustment Korkut Alp Ertürk Ivan Mendieta-Muñoz Working Paper No: 2018-04 June 2018 University of Utah Department of Economics 260 S. Central Campus Dr., Rm. 343 Tel: (801) 581-7481 Fax: (801) 585-5649 http://www.econ.utah.edu 1 The changing dynamics of short-run output adjustment Korkut Alp Ertürk Department of Economics, University of Utah. Email: [email protected] Ivan Mendieta-Muñoz Department of Economics, University of Utah. Email: [email protected] Abstract Much of macroeconomic theorizing rests on assumptions that define the short-run output adjustment of a mass-production economy. The demand effect of investment on output, assumed much faster than its supply effect, works through employment expanding pari passu with changes in capacity utilization while productivity remains constant. Using linear Structural VAR and Time-Varying Parameter Structural VAR models, we document important changes in the short-run output adjustment in the USA. The link between changes in employment, capacity utilization and investment has weakened, while productivity became more responsive following demand shifts caused by investment since the early 1990s. Keywords: Changes in short-run output adjustment, capacity utilization, employment, mass-production economy, post-Fordism. JEL Classification: B50, E10, E32. Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Minqi Li, Codrina Rada, Rudiger von Arnim, and seminar participants at the University of Utah for helpful comments on a previous version of this paper. All errors are the authors’ responsibility. 2 1. Introduction The paper discusses if some of macroeconomists’ theoretical priors still retain their relevance today, presenting evidence that suggests they no longer might. -

Economics Review of Radical Political

Review of Radical Political Economics http://rrp.sagepub.com/ The Current Economic Crisis in the United States: A Crisis of Over-investment David M. Kotz Review of Radical Political Economics 2013 45: 284 originally published online 6 June 2013 DOI: 10.1177/0486613413487160 The online version of this article can be found at: http://rrp.sagepub.com/content/45/3/284 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Union for Radical Political Economics Additional services and information for Review of Radical Political Economics can be found at: Email Alerts: http://rrp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://rrp.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://rrp.sagepub.com/content/45/3/284.refs.html >> Version of Record - Aug 26, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jun 6, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from rrp.sagepub.com at UNIV OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY on December 20, 2013 RRP45310.1177/0486613413487160Review of Radical Political EconomicsKotz 487160research-article2013 Review of Radical Political Economics 45(3) 284 –294 The Current Economic Crisis © 2013 Union for Radical Political Economics in the United States: A Crisis Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav of Over-investment DOI: 10.1177/0486613413487160 rrpe.sagepub.com David M. Kotz1 Abstract This paper offers an analysis of the current economic crisis in the United States that began in 2008, which is understood not as a business cycle recession but as a structural crisis. It presents a case that the current economic crisis is a particular type of crisis of over-investment, called an asset bubble induced over-investment crisis. -

Overhead Labor and Feedback Effects Between Capacity Utilization And

1 Overhead labor and feedback effects between capacity utilization and income distribution: estimations for the USA economy L´ılian Nogueira Rolim∗ Abstract Empirical studies on the USA have not yet reached a consensus on whether this economy is wage- or profit-led, leading many scholars to scrutinize what drives the results of the empirical models. This study tests some possible explanations raised by previous studies by estimating a VECM to the USA from 1964 to 2010. The results suggest that the profit-led short-run outcome does not hold in the long-run, as Blecker (2016) suggests. Also, workers would stimulate the economy more than supervisors (overhead labor), who are also wage earners, as argued by Palley (2017), but there is no support for causality in these directions. Finally, increases in capacity utilization negatively affect the supervisors' share as argued by Lavoie (2014, 2017), but the long-run effect is positive, suggesting a complex determination of functional income distribution, as capacity utilization affects it in ambiguous ways. Keywords: Demand Regimes, Functional Income Distribution, Within-Wage Dis- tribution, Kaleckian Models. JEL classification: E12, D33, C32. ∗Master's degree holder from the Universit´eParis XIII (France) and master's student at the University of Campinas (Brazil). The author thanks Marc Lavoie, Maxime Gueuder, Eckhard Hein, and the participants of the X Brazilian Keynesian Association Meeting for their comments, as well as Simon Mohun for sharing the database. The usual disclaimers apply. Address for correspondence: Rua Pit´agoras, 353 - Bar~ao Geraldo - Campinas/SP - Brazil; email: [email protected]. 2 1 Introduction The stagnationist literature was inaugurated by Baran and Sweezy(1966) and Steindl(1976, 1979), who were analyzing what seemed to be, at their time, a tendency of stagnation in rich countries related to an inelastic profit function that prevented an increase of the wage share that would stimulate demand. -

Capacity Utilization and the NAIRCU Federico Bassi

Capacity Utilization and the NAIRCU Federico Bassi To cite this version: Federico Bassi. Capacity Utilization and the NAIRCU: Evidences of Hysteresis in EU countries. 2019. hal-02360456 HAL Id: hal-02360456 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02360456 Preprint submitted on 12 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Centre d’économie de l’Université Paris Nord CEPN CNRS UMR n° 7234 Document de travail N° 2019-09 Axe : Dynamiques du Capitalisme et Analyses Post-Keynésiennes Capacity Utilization and the NAIRCU Evidences of Hysteresis in EU countries Federico Bassi, [email protected] CEPN, Université Paris 13, Sorbonne Paris Cité October 2019 Abstract: Most empirical studies provide evidence that the rate of capacity utilization is stable around a constant Non-accelerating inflation rate of capacity utilization (NAIRCU). Neverthe- less, available statistical series of the rate of capacity utilization, which is unobservable, are constructed by assuming that it is stable over time. Hence, the stability of the NAIRCU is an ar- tificial artefact. In this paper, we develop a method to estimate the rate of capacity utilization without imposing stability constraints. Partially inspired to the Production function methodology (PFM), we estimate the parameters of a production function by imposing aggregate correlations between the rate of capacity utilization and a set of macroeconomic variables, namely invest- ment, labor productivity and unemployment. -

Measuring Capacity Utilization in Manufacturing

Winter 1976 Measuring Capacity Utilization in Manufacturing by James F. Ragan Capacity utilization rates play an important role in there is no one “best” measure for all purposes, over evaluating economic activity. They have been used, all the FRB utilization rate probably reflects current along with other factors, to explain the behavior of utilization of capital stock most accurately, provided investment, inflation, productivity, profits, and output. that the statistical relationships on which it is based In addition, information on capacity utilization can aid are kept up to date. Finally, based on present utiliza businessmen and economists in assessing current tion rates, the prospects for capacity problems in economic conditions and forecasting future activity. manufacturing over the next year or so appear remote. Unfortunately, alternative measures of capacity utili This is true for key manufacturing subsectors as well zation do not always tell the same story. There are as for aggregate manufacturing. frequent discrepancies between the levels of the vari ous series as well as discrepancies in their movements. Capacity—an elusive concept The purpose of this article is twofold: (1) to examine Capacity refers to the quantity of output that can be how well alternative measures of capacity utilization produced in a fixed period of time, given the existing seem to reflect the current availability of unused capi stock of capital. There are, however, a number of inter tal stock and (2) to assess the current capacity situa pretations for the expression “can be produced”. The tion in manufacturing. engineering interpretation relates to the quantity of There are four principal measures of capacity utili output that could be turned out if, apart from required zation in manufacturing— those of the Wharton School, maintenance, plants and equipment were operated the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System around the clock seven days a week.