1 State-Building in Borderlands: Some “Equatorian” Responses to the SPLM/A Directed Order in Southern Sudan Aleksi Ylönen U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan Conflict Insight | Aug 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT South Sudan Conflict The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision-making Insight and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Tsion Belay Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis The area that is today’s South Sudan was once a marginalized region in the EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Republic of Sudan administered by tribal chiefs during the British colonial Ms. Michelle Mendi Muita period (1899-1955). In the 1950s, marginalization gave rise to the Anyanya Mr. Mikias Yitbarek I rebellion, spearheaded by southern Sudanese separatists and resulting in Ms. Siphokazi Mnguni the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972). The war ended after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, only for another civil war to break out in 1983 instigated by the Sudan People Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), one of the longest civil wars on © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, record, officially ended in 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. Peace Agreement (CPA) by the SPLM/A and the government of Sudan. In 2011, six years after the end of the civil war, South Sudan gained August 2018 | Vol. 2 independence from the Republic of Sudan. South Sudan is home to more than 60 ethnic groups, with the Dinka and CONTENTS the Nuer constituting the largest numbers. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013

Government of the Republic of South Sudan South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013 Realising freedom, equality, justice, peace and prosperity for all Juba, August 2011 0 Contents 0.1 Table of abbreviations and acronyms v 0.2 Foreword xi 0.3 Acknowledgments xii 0.4 Executive summary xiii 0.4.1 Context: conflict, poverty and economic vulnerability xiii 0.4.2 The development challenge xiii 0.4.3 Development objectives xiv 0.4.4 Governance – institutional strengthening and improving transparency and accountability xvi 0.4.5 Economic development – rural development supported by infrastructure improvements xvii 0.4.6 Social and human development – investing in people xviii 0.4.7 Conflict prevention and security – deepening peace and improving security xix 0.4.8 Cross-cutting issues xx 0.4.9 Government resources and their allocation to support development priorities xx 0.4.10 Donor resources xxi 0.4.11 Implementation xxii 0.4.12 Monitoring and Evaluation xxiii 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE SOUTH SUDAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 1 1.1 Purpose of the South Sudan Development Plan 1 1.2 The development planning process and approach 1 1.3 Coverage of the South Sudan Development Plan 2 1.4 Cross-cutting issues integral to the national development priorities 3 2 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 4 2.1 Historical context 4 2.2 Analysis of conflict 6 2.2.1 Causes of conflict 6 2.2.2 Consequences of conflict 8 2.2.3 Peace-building in South Sudan 8 2.2.4 Recommendations for SSDP 11 2.3 Poverty and human development 12 2.3.1 Demographic context 13 2.3.2 Vulnerability 16 2.3.3 Social -

SS 080906 Peace and Reconciliation Conference in Kit

General James most of that day, Lt. and delegates come back. For by the Eastern Equatoria State governors and aided arbitration between the two helped to Wani made consultative The said committee Peace and Rcconciliation. order Parliamentary Committee on day. This was done in of the meeting the following of prepare the ground for the start the dispute. At the end success of the settlement of to develop the framework for the Reconciliation took chargc and Committce for Peace and the day, the Asscmbly Standing day at 9.00 am. announced the adjournment of the conference ror the following SPEAKER OF CLOSING REMARKS BY HE. JAMES WANJ IGGA, THE 06.09.2008. SOUTHERN SUDAN LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ON Legislative Assembly At 6:00 pm, H.E.James Wani lgga, Speaker of the Southern Sudan two governors for made the closing remarks, conveying congratulatory messagcs to the drawn from the two their successful endeavor to mobilize such a huge mass of people as truly contesting counties of Juba and Magwi. He defined the nature of the dispute arbitration. interstate boarder conflict that required good atmosphere of negotiation and He said that any interstate boarder dispute in Southern Sudan is the direct responsibility of the Southern Sudan Legislative Assembly, which has in place a Specialized Committee headed by Honorable Mary Nyaulang. He went on to express that this Committee was comprised of members who were not a party to the conflict. He said Hon. Mary Nyaulang and Hon. Kundi were both from Western Bahr El Ghazal State; and Hon, Barakat Alfred from Western Equatoria State. -

(UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT THURSDAY, 04 JULY 2013 SOUTH SUDAN • Parliament summons security bosses on harassement and detention (Gurtong) • UJoSS delegation forms branch in Northern Bahr el Ghazal State (Gurtong) • Abductees arrive in Aweil from Sudan following community dialogue forum (Gurtong) • Illegal tax collectors arrested in Aweil (Gurtong) • Western Equatoria State vows no long speeches for independence celebrations • Western Equatoria receives independence celebration money (Anisa Radio) OTHER HIGHLIGHTS • UN USG for peacekeeping to hold a press staekout in Khartoum (African Press Organisation) • UNISFA suspends flights after rebel attack on Kadugli airport – report (Sudantribune.com) • Sudan reacts uneasily to ouster of Egypt’s Morsi from presidency (Sudantribune.com) COMMENTS/ STATEMENTS • Joint Sudan, South Sudan statement on current crisis (Sudan Vision) LINKS TO STORIES FROM THE MORNING MEDIA MONITOR • Five heads of state confirmed for South Sudan’s 2nd independence anniversary (Sudantribune.com) • MPs summon one governor, five ministers over harassments (Catholic Radio Network) • MPs pass Oil Revenue Bill to third reading (Catholic Radio Network) • South Sudan suspends radio station for criticizing government (Reuters) • Media, rights entities protest closue of Lakes state radio (Sudantribune.com) • Allowances for South Sudan police to increase in 2014 (Sudantribune.com) • Warrap government sets up a prosecution-immune anti-cattle force (Eye Radio) • Jonglei Ministry of Local Government launches strategic plan (Gurtong) • Over 1,000 leave Komou Boma over hunger threat (Emmanuel Radio) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMISS Communications & Public Information Office can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. -

05 September

5 Sept 2010 Media Monitoring Report www.unmissions.unmis.org United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office Referendum Watch • Southern MPs submit petition to Kiir protesting demarcation report (Al-Rai Al-Aam) • SPLM, NCP at crossroads over North South border issue – ICG (ST) • NCP, southern parties stress need for free and fair referendum (Al-Ayyam) • Referendum commission nominates Al-Nujoomi Secretary General (Khartoum Monitor) • Referendum Commission prepares voter registration (Sudan Vision) • Referendum budget well above $380 million – Machar (The Citizen) • SSRA set up referendum committee, MPs want official secession drive (the Citizen) • LRA activity will affect referendum – Riek Machar (Sudan Vision) • UNMIS establishes Referendum Base in Western Equatoria state (ST) Other Headlines • VP Taha to lead Sudan’s delegation to UN General Assembly meetings (ST) • Public Order law will remain in force –Khartoum state Government (Al-Sahafa) • Six people killed in fresh attacks on another camp in Darfur – IDPs (ST) • UN pledges $ 15 million for Eastern Equatoria (Al-Sahafa) • NCP downplays ICC move to press Sudan to hand over wanted officials (Al-Ayyam) • SPLM purchased 10 helicopters, SAF says in the know (Ajras Al-Hurriya) • UNMIS Helicopter to transport resolution committee to Acholi-Madi areas (The Citizen) • Machar hits back at Akhir Lahza newspaper (Khartoum Monitor) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMIS PIO can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in Sudan. Furthermore, international copyright exists on some materials and this summary should not be disseminated beyond the intended list of recipients. -

Dual Realities: Peace and War in the Sudan – an Update on the Implementation of the CPA

Institute for Security Studies Situation Report Date Issued: 16 May 2007 Author: M riam Bibi Jooma1 a Distribution: General Contact: [email protected] Dual realities: Peace and war in the Sudan – An update on the implementation of the CPA Global news headlines continue to report the political impasse and consequent Introduction loss of civilian life in Sudan’s western state of Darfur, but there is decidedly less attention on what is essentially a fragile peace between the former warring factions of Northern and Southern Sudan. Indeed, almost 30 months after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in January 2005 there is little confidence that any significant change will occur in what remains of the Interim Period. Certainly the precariousness of the CPA impacts, and will continue to impact, upon both the Darfur Peace Agreement and the Eastern Peace Agreement as it acts as a basic document upon which the legitimacy of the Government of National Unity and the Government of Southern Sudan are based. As the incoming Secretary General of the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon suggested in his opening report on Sudan in January this year, Of central concern, the principles of the Agreement related to political inclusion and “making unity attractive” have yet to be fully upheld, and much remains to be done if the parties are to achieve their ambitious goals set out in the Machakos Protocol and in subsequent Protocols (UN 2007a). This situation report highlights some of the most pressing challenges to the implementation of the CPA from the perspective of the political incumbents, international observers, and sectors of civil society including the Sudanese media. -

Full List of the Historical SPLM/SPLA Commanders, 1983-2005

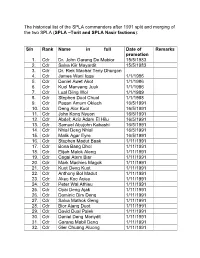

The historical list of the SPLA commanders after 1991 split and merging of the two SPLA (SPLA –Torit and SPLA Nasir factions): S/n Rank Name in full Date of Remarks promotion 1. Cdr Dr. John Garang De Mabior 15/5/1983 2. Cdr Salva Kiir Mayardit 15/5/1983 3. Cdr Dr. Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon 4. Cdr James Wani Igga 1/1/1986 5. Cdr Daniel Awet Akot 1/1/1986 6. Cdr Kuol Manyang Juuk 1/1/1986 7. Cdr Lual Diing Wol 1/1/1989 8. Cdr Stephen Duol Chuol 1/1/1988 9. Cdr Pagan Amum Okiech 16/5/1991 10. Cdr Deng Alor Kuol 16/5/1991 11. Cdr John Kong Nyuon 16/5/1991 12. Cdr Abdel; Aziz Adam El Hilu 16/5/1991 13. Cdr Samuel Abujohn Kabashi 16/5/1991 14. Cdr Nhial Deng Nhial 16/5/1991 15. Cdr Malik Agar Eyre 16/5/1991 16. Cdr Stephen Madut Baak 1/11/1991 17. Cdr Bona Bang Dhol 1/11/1991 18. Cdr Elijah Malok Aleng 1/11/1991 19. Cdr Cagai Atem Biar 1/11/1991 20. Cdr Mark Machiec Magok 1/11/1991 21. Cdr Kuot Deng Kuot 1/11/1991 22. Cdr Anthony Bol Madut 1/11/1991 23. Cdr Akec Koc Acieu 1/11/1991 24. Cdr Peter Wal Athieu 1/11/1991 25. Cdr Oyai Deng Ajak 1/11/1991 26. Cdr Dominic Dim Deng 1/11/1991 27. Cdr Salva Mathok Geng 1/11/1991 28. Cdr Bior Ajang Duot 1/11/1991 29. -

Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2016

A/HRC/31/CRP.6 Advance version Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2016 English only Human Rights Council Thirty-first session Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Assessment mission by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to improve human rights, accountability, reconciliation and capacity in South Sudan: detailed findings* Summary This present document contains the detailed findings of the comprehensive assessment conducted by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) into allegations of violations and abuses of human rights and violations of international humanitarian law in South Sudan since the outbreak of violence in December 2013. It should be read in conjunction with the report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the assessment mission to South Sudan submitted to the Human Rights Council at its thirty-first session (A/HRC/31/49). * Reproduced as received. A/HRC/31/CRP.6 Contents Page Part 1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 6 I. Establishment of the OHCHR Assessment Mission to South Sudan ............................................... 8 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 8 B. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... -

(UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT MONDAY, 08 JULY 2013 SOUTH SUDAN South Sudan’s 2nd birthday (Al-Jazeera News) Friends of S. Sudan’ go public with call for "significant changes and reform" (Sudantribune.com) Dr. Tedros Receives South Sudan's Foreign Minister (AllAfrica.com) South Sudan not a failed state: British Envoy (Gurtong.net) O3b’s new satellite constellation to provide high speed connectivity to S. Sudan (Business Wire) Youth want leader to step down for abuse of office (Gurtong.net) Japan boosts Ministry of Health with USD 4 million by Anthony Wani (Theniles.org) South Sudanese students in Egypt meet government delegation (Gurtong.net) CARE International assists vulnerable communities in Unity state (Sudantribune.com) Organization distributes treated mosquito nets to curb malaria spread (Gurtong.net) SOUTH SUDAN, SUDAN FM to represent Sudan in S. Sudan national day celebrations (Sudanvisiondaily.com) Sudan MiG-29s said to conduct air strikes on South (Worldtribune.com) SAF denies Juba accusations of fresh attacks on border areas (Sudantribune.com) Now is the time for Arab Unity; Nafie (Sudanvisiondaily.com) Eritrea’s leader says comprehensive strategy key to resolve Sudans disputes (Sudantribune.com) South Sudan’s FM briefs Ethiopian PM about recent talks with Khartoum (Sudantribune.com) Juba says Khartoum wants to buy 4,500 barrels of oil for Kosti power plant (Sudantriibune.com) Sudan will not shut oil