Advance Version Distr.: Restricted 10 March 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Commission and Sudanese Authorities Sign the Country Strategy Paper to Resume Co- Operation

IP/05/94 Brussels, 25 January 2005 European Commission and Sudanese authorities sign the Country Strategy Paper to resume co- operation Following the signature of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the Government of the Sudan and the SPLM/A in Nairobi on 9 January 2005, the European Commission and the Government of the Sudan have finalised the Country Strategy Paper (CSP) for their cooperation. This document includes the National Indicative Programme and will be signed at 15h30 on 25 January 2005 by the Minister for International Co-operation, Mr. Takana, and the European Commissioner for Development, Mr. L. Michel. The President of the European Commission, Mr. J.M. Barroso, the Vice-president of the Sudan, Mr. Taha and Mr. Nhial Deng Nhial, Commissioner for External relations of the SPLM, will witness the signature. In November 1999, after 9 years of suspension of co-operation, the EU and the Sudan engaged in a formal Political Dialogue. Since December 2001, the Dialogue has been intensified with a view to a gradual resumption of co-operation once a Comprehensive Peace Agreement would be signed. The European Union has been clearly linking its future relations with the Sudan to the signing of a Comprehensive Peace Agreement. The Agreement is considered in particular as a basis to integrate in a global process the other marginalised areas of Sudan, including Darfur. The signature of the CSP should be considered a first step to normalise the Commisison’s relations with the Government of the Sudan. Its implementation will be gradual and in parallel to the effective implementation of the peace agreement and the improvement of the situation in the Darfur. -

South Sudan Conflict Insight | Aug 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT South Sudan Conflict The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision-making Insight and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Tsion Belay Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis The area that is today’s South Sudan was once a marginalized region in the EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Republic of Sudan administered by tribal chiefs during the British colonial Ms. Michelle Mendi Muita period (1899-1955). In the 1950s, marginalization gave rise to the Anyanya Mr. Mikias Yitbarek I rebellion, spearheaded by southern Sudanese separatists and resulting in Ms. Siphokazi Mnguni the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972). The war ended after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, only for another civil war to break out in 1983 instigated by the Sudan People Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), one of the longest civil wars on © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, record, officially ended in 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. Peace Agreement (CPA) by the SPLM/A and the government of Sudan. In 2011, six years after the end of the civil war, South Sudan gained August 2018 | Vol. 2 independence from the Republic of Sudan. South Sudan is home to more than 60 ethnic groups, with the Dinka and CONTENTS the Nuer constituting the largest numbers. -

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

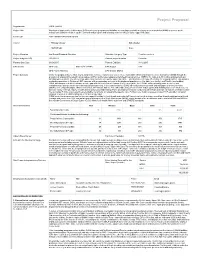

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack Table of Contents Page No. Table of Contents 1 State Map 2 Overview 3 Security and Political History 3 Major Conflicts 4 State Government Structure 6 Recovery and Development 7 State Resident Coordinator’s Support Office 8 Organizations Operating in the State 9-11 1 Map of Upper Nile State 2 Overview The state of Upper Nile has an area of 77,773 km2 and an estimated population of 964,353 (2009 population census). With Malakal as its capital, the state has 13 counties with Akoka being the most recent. Upper Nile shares borders with Southern Kordofan and Unity in the west, Ethiopia and Blue Nile in the east, Jonglei in the south, and White Nile in the north. The state has four main tribes: Shilluk (mainly in Panyikang, Fashoda and Manyo Counties), Dinka (dominant in Baliet, Akoka, Melut and Renk Counties), Jikany Nuer (in Nasir and Ulang Counties), Gajaak Nuer (in Longochuk and Maiwut), Berta (in Maban County), Burun (in Maban and Longochok Counties), Dajo in Longochuk County and Mabani in Maban County. Security and Political History Since inception of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), Upper Nile State has witnessed a challenging security and political environment, due to the fact that it was the only state in Southern Sudan that had a Governor from the National Congress Party (NCP). (The CPA called for at least one state in Southern Sudan to be given to the NCP.) There were basically three reasons why Upper Nile was selected amongst all the 10 states to accommodate the NCP’s slot in the CPA arrangements. -

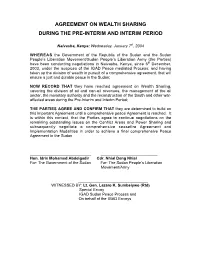

Agreement on Wealth Sharing During the Pre-Interim and Interim Period

AGREEMENT ON WEALTH SHARING DURING THE PRE-INTERIM AND INTERIM PERIOD Naivasha, Kenya: Wednesday, January 7th, 2004 WHEREAS the Government of the Republic of the Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Sudan People’s Liberation Army (the Parties) have been conducting negotiations in Naivasha, Kenya, since 6th December, 2003, under the auspices of the IGAD Peace mediated Process; and having taken up the division of wealth in pursuit of a comprehensive agreement, that will ensure a just and durable peace in the Sudan; NOW RECORD THAT they have reached agreement on Wealth Sharing, covering the division of oil and non-oil revenues, the management of the oil sector, the monetary authority and the reconstruction of the South and other war- affected areas during the Pre-Interim and Interim Period; THE PARTIES AGREE AND CONFIRM THAT they are determined to build on this important Agreement until a comprehensive peace Agreement is reached. It is within this context, that the Parties agree to continue negotiations on the remaining outstanding issues on the Conflict Areas and Power Sharing and subsequently negotiate a comprehensive ceasefire Agreement and Implementation Modalities in order to achieve a final comprehensive Peace Agreement in the Sudan. ____________________________ __________________________ Hon. Idris Mohamed Abdelgadir Cdr. Nhial Deng Nhial For: The Government of the Sudan For: The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army ________________________________ WITNESSED BY: Lt. Gen. Lazaro K. Sumbeiywo (Rtd) Special Envoy IGAD -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 Update)

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 update) Three months have elapsed since widespread conflict broke out in South Sudan, and Malakal, Upper Nile’s state capital, remains deserted and largely burned to the ground. The state is patchwork of zones of control, with the rebels holding the largely Nuer south (Longochuk, Maiwut, Nasir, and Ulang counties), and the government retaining the north (Renk), east (Maban and Melut), and the crucial areas around Upper Nile’s oil fields. The rest of the state is contested. The conflict in Upper Nile began as one between different factions within the SPLA but has now broadened to include the targeted ethnic killing of civilians by both sides. With the status of negotiations in Addis Ababa unclear, and the rebel’s 14 March decision to refuse a regional peacekeeping force, conflict in the state shows no sign of ending in the near future. With the first of the seasonal rains now beginning, humanitarian costs of ongoing conflict are likely to be substantial. Conflict began in Upper Nile on 24 December 2013, after a largely Nuer contingent of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) 7th division, under the command of General Gathoth Gatkuoth, declared their loyalty to former vice-president Riek Machar and clashed with government troops in Malakal. Fighting continued for three days. The central market was looted and shops set on fire. Clashes also occurred in Tunja (Panyikang county), Wanding (Nasir county), Ulang (Ulang county), and Kokpiet (Baliet county), as the SPLA’s 7th division fragmented, largely along ethnic lines, and clashed among themselves, and with armed civilians. -

South Sudan 2015 Human Rights Report

SOUTH SUDAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Sudan is a republic operating under a transitional constitution signed into law upon declaration of independence from Sudan in 2011. President Salva Kiir Mayardit, whose authority derives from his 2010 election as president of what was then the semiautonomous region of Southern Sudan within the Republic of Sudan, led the country. While the 2010 Sudan-wide elections did not wholly meet international standards, international observers believed Kiir’s election reflected the will of a large majority of Southern Sudanese. International observers considered the 2011 referendum on South Sudanese self-determination, in which 98 percent of voters chose to separate from Sudan, to be free and fair. President Kiir is a founding member of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) political party, the political wing of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Of the 27 ministries, only 21 had appointed ministers in charge, of which 19 are SPLM representatives. The bicameral legislature consists of 332 seats in the National Legislative Assembly (NLA), of which 296 were filled, and 50 seats in the Council of States. SPLM representatives controlled the vast majority of seats in the legislature. Through presidential decrees Kiir replaced eight of the 10 state governors elected since 2010. The constitution states that an election must be held within 60 days if an elected governor has been relieved by presidential decree. This has not happened. The legislature lacked independence, and the ruling party dominated it. Civilian authorities failed at times to maintain effective control over the security forces. In 2013 armed conflict between government and opposition forces began after violence erupted within the Presidential Guard Force (PG) of the SPLA, also known as the Tiger Division. -

1.1 Million 3.2 Million 4.9 Million

South Sudan Crisis Situation report as of 10 April 2014 Report number 31 This report is produced by OCHA South Sudan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 4 to 10 April 2014. The next report will be published on or around 18 April 2014. Highlights Clashes were reported in northern Upper Nile State, with tension mounting in and around Melut. So far, aid agencies have reached around 1.1 million people, around one third of the people to be assisted by June. Over 960,000 people have been reached with medical interventions. Over 100,000 people are reported to be displaced in and around Kodok, Lul and Wau Shiluk in Upper Nile State. They are in urgent need of assistance. Multi-sector rapid response was ongoing in eight locations in Jonglei, Unity and Upper Nile states, with partners also ready to begin response in Kodok, Upper Nile State. 4.9 million 3.2 million 1.1 million 817,700 People in need of People to be assisted People reached with People internally humanitarian by aid organizations by humanitarian displaced by violence assistance June assistance* since 15 Dec 2013 *This includes people internally displaced, refugees from other countries sheltering in South Sudan and other vulnerable communities who have received assistance since January 2014. This does not mean that the needs of these people have been comprehensively met. Situation overview Clashes were reported in Upper Nile State the Central Equatoria Jonglei 250,000 last days, including in Kaka, 40 kilometres northwest of Melut on 7-8 April, heightening Lakes Unity 200,000 tension in the state and causing some pre- Upper Nile emptive movements of people.