Conflict in Western Equatoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Western Equatoria Infographic V6 Final

Joint report by United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Report on violations and abuses against civilians in Gbudue April–August and Tambura States, Western Equatoria 2018 INTRODUCTION This report is jointly published by the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), pursuant to United Nations Security Council resolution 2406 (2018). The report presents the ndings of an investigation conducted by the UNMISS Human Rights Division (UNMISS HRD) into violations and abuses of international human rights law and violations of international humanitarian law reportedly committed by the pro-Machar Sudan People’s Liberation Army in Opposition (SPLA-IO (RM)) and the Government’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) against civilians in the states of Gbudue and Tambura, in Western Equatoria, between April and August 2018. The report documents the plight of civilians in the Western Equatoria region of South Sudan, where increased violence and attacks between April and August 2018 saw nearly 900 people abducted, including 505 women, and forced into sexual slavery or combat, and over 24,000 displaced from their homes. The report identies three SPLA-IO commanders who may bear the greatest responsibility for the violence committed against the civilian population in Western Equatoria during the period under consideration. HRD employed the standard of proof of reasonable grounds to believe in making factual determinations about the violations and abuses incidents, and patterns of conduct of the perpetrators. Unless specically stated, all information in the report has been veried using several independent, credible and reliable sources, in accordance with OHCHR’s human rights monitoring and investigation methodology. -

South Sudan Conflict Insight | Aug 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT South Sudan Conflict The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision-making Insight and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Tsion Belay Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis The area that is today’s South Sudan was once a marginalized region in the EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Republic of Sudan administered by tribal chiefs during the British colonial Ms. Michelle Mendi Muita period (1899-1955). In the 1950s, marginalization gave rise to the Anyanya Mr. Mikias Yitbarek I rebellion, spearheaded by southern Sudanese separatists and resulting in Ms. Siphokazi Mnguni the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972). The war ended after the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement, only for another civil war to break out in 1983 instigated by the Sudan People Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), one of the longest civil wars on © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, record, officially ended in 2005 with the signing of the Comprehensive Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. Peace Agreement (CPA) by the SPLM/A and the government of Sudan. In 2011, six years after the end of the civil war, South Sudan gained August 2018 | Vol. 2 independence from the Republic of Sudan. South Sudan is home to more than 60 ethnic groups, with the Dinka and CONTENTS the Nuer constituting the largest numbers. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

2011 South Sudan Education Statistical Booklet

Education Statistics for Western Equatoria Government of Republic of South Sudan Ministry of General Education and Instruction State Statistical Booklet Western Equatoria Republic of South Sudan Ministry of General Education and Instruction Directorate of Planning and Budgeting Department of Data and Statistics Education Management Information Systems Unit Juba, South Sudan www.goss.org © Ministry of General Education and Instruction 2012 This publication may be used as a part or as a whole, provided that the MoGEI is acknowledged as the source of information. This publication has been produced with financial and technical support from UNICEF, FHI360, and SCiSS. For inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: George Mogga / Director for Planning and Budgeting / [email protected] Fahim Akbar / Senior EMIS Advisor / [email protected] Moses Kong / EMIS Officer / [email protected] Paulino Kamba / EMIS Officer / [email protected] Joanes Odero / Programme Associate / [email protected] Deng Chol Deng / Programme Associate / [email protected] 1 Foreword Message from Minister Joseph Ukel Abango On behalf of the Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MoGEI), I am pleased for the fifth education census data for the Republic of South Sudan (RSS). The collection and consolidation of the Education Management Information System (EMIS) have come a long way since the baseline assessment, or the Rapid Assessment of Learning Spaces (RALS) conducted in 2006. RALS covered less than half of the primary schools operating in the country at the time. By 2011, data from pre-primary, primary, secondary, an Alternative Education Systems (AES), and technical and vocational education and training (TVET) schools, centres, and institutes were collected. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

09.04.20 South Sudan Program

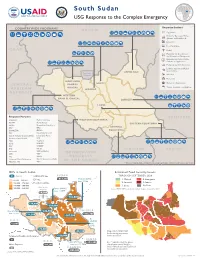

South Sudan USG Response to the Complex Emergency COUNTRYWIDE PROGRAMS Response Sectors: SUDAN Agriculture Economic Recovery, Market Systems, and Livelihoods Education Food Assistance CHAD Health Humanitarian Coordination and Information Management Humanitarian Policy, Studies, Analysis, or Application Multipurpose Cash Assistance Logistics Support and Relief Commodities Abyei Area- UPPER NILE Disputed* Nutrition Protection NORTHERN UNITY Shelter and Settlements CENTRAL BAHR EL GHAZAL Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene AFRICAN WARRAP REPUBLIC WESTERN BAHR EL GHAZAL JONGLEI LAKES Response Partners: ETHIOPIA AAH/USA Mentor Initiative WESTERN EQUATORIA ACTED Mercy Corps EASTERN EQUATORIA ALIMA Nonviolent Peaceforce ARC NRC CENTRAL CONCERN OCHA EQUATORIA CRS Relief International Danish Refugee Council (DRC) Samaritan's Purse Doctors of the World SCF FAO Tearfund ICRC UNHCR IFRC UNICEF IMC VSF/G UGANDA KENYA Internews WFP (UNHAS) IOM WFP DEMOCRATIC IRC WHO REPUBLIC Lutheran World Federation World Vision, Inc. (USA) MEDAIR, SWI WRI OF THE CONGO * Final sovereignty status of Abyei Area pending negotiations between South Sudan and Sudan. IDPs in South Sudan Estimated Food Security Levels # By State " UNMISS IDP Site SUDAN THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2020 # Malakal UNMISS 1: Minimal 4: Emergency 60,000 - 100,000 IDP Site ~813,300 base: 27,900 100,000 - 150,000 Host Communities # 2: Stressed 5: Famine 150,000 - 200,000 ## 3: Crisis No Data Abyei Area - 200,000 - 250,000 Bentiu UNMISS Disputed # Source: FEWS NET, South Sudan Outlook, August - September 2020 base: 111,800 ~9,300 ## ## # # ~233,800# # ## # ##"# # # #"# # ### # #~76,400 # # # ~226,000 # # # # # # # ### Wau UNMISS # ETHIOPIA ##~246,700 # base: 10,000 #"## # ~71,200 ~346,300 # # ~207,200 # ~187,200 # # Bor C.A.R. UNMISS # ~2,600 #"# base: # # 1,900 ## # ~70,900 ## # # # ~60,100 Map reflects FEWS NET # ##"# # # # food security projections # Refugees in Neighboring Countries #~220,800 # at the area level. -

Wfp256400.Pdf

Acknowledgements This report is a collaborative effort of the Republic of South Sudan ministries, UN agencies and development partners. These include: Food Security Technical Secretariat (FSTS), National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MoAF), Ministry of Animal Resources and Fisheries (MoARF), Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) and Ministry of Health (MoH). The activity was funded by the World Food Programme (WFP). The UN agencies included: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Food Programme, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). We gratefully acknowledge support provided by Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and all partners of the Food Security and Livelihoods and Nutrition clusters for their invaluable inputs and the ANLA Technical Working Group (chaired by FSTS) that dedicated their time to contribute different chapters of the report. We especially thank Manase Yanga Laki, Elijah Luak (MoAF), Bernard Owadi, Idiku Michael, Hersi Mohamud, Gummat Abdallatif, Yomo Lawrence (WFP VAM Team), Elijah Mukhala (FAO), Mtendere Mphatso (FSL Cluster), Gloria Kusemererwa of WFP Nutrition Unit who prepared specific chapters of the report. Overall technical editing and layout of the report was done by WFP VAM Unit. Last but not least we thank all the men and women who braved difficult terrain and long travel hours to provide the empirical data used for this report. For questions or comments concerning -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013

Government of the Republic of South Sudan South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013 Realising freedom, equality, justice, peace and prosperity for all Juba, August 2011 0 Contents 0.1 Table of abbreviations and acronyms v 0.2 Foreword xi 0.3 Acknowledgments xii 0.4 Executive summary xiii 0.4.1 Context: conflict, poverty and economic vulnerability xiii 0.4.2 The development challenge xiii 0.4.3 Development objectives xiv 0.4.4 Governance – institutional strengthening and improving transparency and accountability xvi 0.4.5 Economic development – rural development supported by infrastructure improvements xvii 0.4.6 Social and human development – investing in people xviii 0.4.7 Conflict prevention and security – deepening peace and improving security xix 0.4.8 Cross-cutting issues xx 0.4.9 Government resources and their allocation to support development priorities xx 0.4.10 Donor resources xxi 0.4.11 Implementation xxii 0.4.12 Monitoring and Evaluation xxiii 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE SOUTH SUDAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 1 1.1 Purpose of the South Sudan Development Plan 1 1.2 The development planning process and approach 1 1.3 Coverage of the South Sudan Development Plan 2 1.4 Cross-cutting issues integral to the national development priorities 3 2 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 4 2.1 Historical context 4 2.2 Analysis of conflict 6 2.2.1 Causes of conflict 6 2.2.2 Consequences of conflict 8 2.2.3 Peace-building in South Sudan 8 2.2.4 Recommendations for SSDP 11 2.3 Poverty and human development 12 2.3.1 Demographic context 13 2.3.2 Vulnerability 16 2.3.3 Social -

SS 080906 Peace and Reconciliation Conference in Kit

General James most of that day, Lt. and delegates come back. For by the Eastern Equatoria State governors and aided arbitration between the two helped to Wani made consultative The said committee Peace and Rcconciliation. order Parliamentary Committee on day. This was done in of the meeting the following of prepare the ground for the start the dispute. At the end success of the settlement of to develop the framework for the Reconciliation took chargc and Committce for Peace and the day, the Asscmbly Standing day at 9.00 am. announced the adjournment of the conference ror the following SPEAKER OF CLOSING REMARKS BY HE. JAMES WANJ IGGA, THE 06.09.2008. SOUTHERN SUDAN LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ON Legislative Assembly At 6:00 pm, H.E.James Wani lgga, Speaker of the Southern Sudan two governors for made the closing remarks, conveying congratulatory messagcs to the drawn from the two their successful endeavor to mobilize such a huge mass of people as truly contesting counties of Juba and Magwi. He defined the nature of the dispute arbitration. interstate boarder conflict that required good atmosphere of negotiation and He said that any interstate boarder dispute in Southern Sudan is the direct responsibility of the Southern Sudan Legislative Assembly, which has in place a Specialized Committee headed by Honorable Mary Nyaulang. He went on to express that this Committee was comprised of members who were not a party to the conflict. He said Hon. Mary Nyaulang and Hon. Kundi were both from Western Bahr El Ghazal State; and Hon, Barakat Alfred from Western Equatoria State. -

(UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT THURSDAY, 04 JULY 2013 SOUTH SUDAN • Parliament summons security bosses on harassement and detention (Gurtong) • UJoSS delegation forms branch in Northern Bahr el Ghazal State (Gurtong) • Abductees arrive in Aweil from Sudan following community dialogue forum (Gurtong) • Illegal tax collectors arrested in Aweil (Gurtong) • Western Equatoria State vows no long speeches for independence celebrations • Western Equatoria receives independence celebration money (Anisa Radio) OTHER HIGHLIGHTS • UN USG for peacekeeping to hold a press staekout in Khartoum (African Press Organisation) • UNISFA suspends flights after rebel attack on Kadugli airport – report (Sudantribune.com) • Sudan reacts uneasily to ouster of Egypt’s Morsi from presidency (Sudantribune.com) COMMENTS/ STATEMENTS • Joint Sudan, South Sudan statement on current crisis (Sudan Vision) LINKS TO STORIES FROM THE MORNING MEDIA MONITOR • Five heads of state confirmed for South Sudan’s 2nd independence anniversary (Sudantribune.com) • MPs summon one governor, five ministers over harassments (Catholic Radio Network) • MPs pass Oil Revenue Bill to third reading (Catholic Radio Network) • South Sudan suspends radio station for criticizing government (Reuters) • Media, rights entities protest closue of Lakes state radio (Sudantribune.com) • Allowances for South Sudan police to increase in 2014 (Sudantribune.com) • Warrap government sets up a prosecution-immune anti-cattle force (Eye Radio) • Jonglei Ministry of Local Government launches strategic plan (Gurtong) • Over 1,000 leave Komou Boma over hunger threat (Emmanuel Radio) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMISS Communications & Public Information Office can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. -

05 September

5 Sept 2010 Media Monitoring Report www.unmissions.unmis.org United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office Referendum Watch • Southern MPs submit petition to Kiir protesting demarcation report (Al-Rai Al-Aam) • SPLM, NCP at crossroads over North South border issue – ICG (ST) • NCP, southern parties stress need for free and fair referendum (Al-Ayyam) • Referendum commission nominates Al-Nujoomi Secretary General (Khartoum Monitor) • Referendum Commission prepares voter registration (Sudan Vision) • Referendum budget well above $380 million – Machar (The Citizen) • SSRA set up referendum committee, MPs want official secession drive (the Citizen) • LRA activity will affect referendum – Riek Machar (Sudan Vision) • UNMIS establishes Referendum Base in Western Equatoria state (ST) Other Headlines • VP Taha to lead Sudan’s delegation to UN General Assembly meetings (ST) • Public Order law will remain in force –Khartoum state Government (Al-Sahafa) • Six people killed in fresh attacks on another camp in Darfur – IDPs (ST) • UN pledges $ 15 million for Eastern Equatoria (Al-Sahafa) • NCP downplays ICC move to press Sudan to hand over wanted officials (Al-Ayyam) • SPLM purchased 10 helicopters, SAF says in the know (Ajras Al-Hurriya) • UNMIS Helicopter to transport resolution committee to Acholi-Madi areas (The Citizen) • Machar hits back at Akhir Lahza newspaper (Khartoum Monitor) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMIS PIO can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in Sudan. Furthermore, international copyright exists on some materials and this summary should not be disseminated beyond the intended list of recipients.