“Both Sides, Now”: Voice, Affect, and Thirdness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs About Joni

Songs About Joni Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2003 Latest Update: Dec. 28, 2020 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] © Ed Thrasher, March 1968 Song Title Musician Album / CD Title 1967 Lady Of Rohan Chuck Mitchell Unreleased 1969 Song To A Cactus Tree Graham Nash Unreleased Why, Baby Why Graham Nash Unreleased Guinnevere Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Pre-Road Downs Crosby, Stills & Nash Crosby, Stills & Nash Portrait Of The Lady As A Young Artist Seatrain Seatrain (Debut LP) 1970 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Neil Young After The Goldrush Our House Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Déjà Vu 1971 Just Joni Mitchell Charles John Quarto Unreleased Better Days Graham Nash Songs For Beginners I Used To Be A King Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Simple Man Graham Nash Songs For Beginners Love Has Brought Me Around James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon You Can Close Your Eyes James Taylor Mudslide Slim & The Blue Horizon 1972 New Tune James Taylor One Man Dog 1973 It's Been A Long Time Eric Andersen Stages: The Lost Album You'’ll Never Be The Same Graham Nash Wild Tales Song For Joni Dave Van Ronk songs for ageing children Sweet Joni Neil Young Unreleased Concert Recording 1975 She Lays It On The Line Ronee Blakley Welcome Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Wind On The Water 1976 I Used To Be A King David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Simple Man David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Mama Lion David Crosby / Graham Nash Crosby-Nash LIVE Song For Joni Denise Kaufmann Dream Flight Mellow -

Stephanie Orfano Is the Social Science Librarian at the Downtown Oshawa Branch of the University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT)

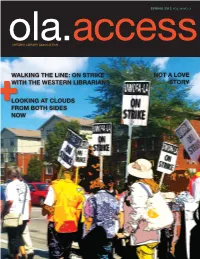

SPRING 2012 vol.18 no. 2 ola.ontario library association access WALKING THE LINE: ON STRIKE NOT A LOVE WITH THE WESTERN LIBRARIANS STORY LOOKING AT CLOUDS FROM BOTH SIDES NOW PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 1 12-03-31 1:11 PM Call today to request your Free catalogue! • Library Supplies • Computer Furniture • Office Furniture • Library Shelving • Book & Media Display • Reading Promotions • Early Learning • Book Trucks • Archival Supplies Call • 1.800.268.2123 Fax • 1.800.871.2397 Shop Online • www.carrmclean.ca PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 2 12-03-31 1:11 PM spring 2012 18:2 contents Features Call today to request Features your Free 11 Risk, Solidarity, Value 21 La place de la bibliothèque publique dans la catalogue! by Kristin hoffmann culture franco-ontarienne During the recent strike by librarians at the University of par steven Kraus Western Ontario, Kristin Hoffmann learned a lot about Vive les bibliothèques publiques du Grand Nord! Steven • Library Supplies her profession, her colleagues and herself. Kraus fait témoignage du rôle que joue la bibliothèque publique dans la promotion de la francophonie. • Computer Furniture 14 Not a Love Story by lisa sloniowsKi 22 Cloudbusting Creating an archive of feminist pornography raises by nicK ruest & john finK • Office Furniture many questions about libraries, librarians, our values and Is all this "cloud" hype ruining your sunny day? Nick • Library Shelving our responsibilities. Lisa Sloniowski guides us through this Ruest and John Fink clear the air and make it all right. The controversial area. forecast is good. • Book & Media Display 18 Visualizing Your Research 24 Governance 101: CEO Evaluation by jenny marvin by jane HILTON • Reading Promotions GeoPortal from Scholars Portal won this year's OLITA As our series on governance continues, Jane Hilton focuses Award for Technological Innovation. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection

Search artists, albums and more... ' Explore + Marketplace + Community + * ) + Dashboard Collection Wantlist Lists Submissions Drafts Export Settings Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection Collection Value:* Min $3,698.90 Med $9,882.74 Max $29,014.80 Sort Artist A-Z Folder Keepers (500) Show 250 $ % & " Remove Selected Keepers (500) ! Move Selected Artist #, Title, Label, Year, Format Min Median Max Added Rating Notes Johnny Cash - American Recordings $43.37 $61.24 $105.63 over 5 years ago ((((( #366 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release American Recordings, American Recordings 9-45520-1, 1-45520 Near Mint (NM or M-) Shrink 1994 US Johnny Cash - At Folsom Prison $4.50 $29.97 $175.84 over 5 years ago ((((( #88 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Very Good Plus (VG+) US 1st Release Columbia CS 9639 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1968 US Johnny Cash - With His Hot And Blue Guitar $34.99 $139.97 $221.60 about 1 year ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Mic Very Good Plus (VG+) top & spine clear taped Sun (9), Sun (9), Sun (9) 1220, LP-1220, LP 1220 Very Good (VG) 1957 US Joni Mitchell - Blue $4.00 $36.50 $129.95 over 6 years ago ((((( #30 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album, Pit Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release Reprise Records MS 2038 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1971 US Joni Mitchell - Clouds $4.03 $15.49 $106.30 over 2 years ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Ter Near Mint (NM or M-) Reprise Records RS 6341 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1969 US Joni Mitchell - Court And Spark $1.99 $5.98 $19.99 -

012521-DRAFT-Bothsidesnow

Both Sides Now: Singer-Songwriters Then and Now An Etz Chayim Fifth Friday SHABBAT SERVICE Kabbalat Shabbat • Happy • Shower the People You Love With Love L’Cha Dodi (to Sweet Baby James) Bar’chu • Creation: Big Yellow Taxi • Revelation: I Choose Y0u Sh’ma • Both Sides Now + Traditional Prayer • V’ahavta: All Of Me • Redemption: Brave Hashkiveynu / Lay Us Down: Beautiful Amidah (“Avodah” / Service) • Avot v’Imahot: Abraham’s Daughter • G’vurot: Music To My Eyes • K’dushat haShem: Edge Of Glory • R’Tzeih: Chelsea Morning • Modim: The Secret Of LIfe • Shalom: Make You Feel My Love (instrumental & reflection) D’Var Torah • Miriam’s Song Congregation Etz Chayim Healing Prayer: You’ve Got a Friend Palo Alto, CA Aleynu Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky Mourners’ Kaddish: Fire And Rain + Traditional Prayer Birchot Hamishpachah / Parents Bless their Children: Circle Game + Inclusive Blessing of Children Closing Song: Adon Olam (to Hallelujah) Both Sides Now Shabbat, 1/29/21 • Shabbat Evening Service, page 1 Kavannah for Our Service For this Fifth Friday Shabbat service we will experience songs by a diverse array of singer- songwriters in place of many of our traditional prayers. The intent is to lift up the prayers by viewing them through a new lens, and perhaps gain new insight into beloved, contemporary songs, whether familiar or new to us. “Both Sides Now” speaks to several relevant themes in our service and in our hearts: • This week’s Torah portion, B’Shallah, begins with our Israeilite ancestors in slavery, on one side of the Sea of Reeds and ends with them as a newly freed people on the other side. -

Scholastic Inc. Out-Of-Print Notification: Pw Advertisement

SCHOLASTIC INC. OUT-OF-PRINT NOTIFICATION: PW ADVERTISEMENT MAY 1, 2006 RETURNS DUE BY AUGUST 28, 2006 Please note: other editions or formats of these titles may exist in print under different ISBNs. ISBN Title 0590338730 ACTS OF LOVE (HC) 0590435469 ADVENTURES OF BOONE BARNABY, THE (HC) 0590445855 ALBIE THE LIFEGUARD (HC) 0590434284 ALICE AND THE BIRTHDAY GIANT (HC) 0590403206 ALIENS IN THE FAMILY (HC) 0590443828 ALIGAY SAVES THE STARS (HC) 0590432125 ANGELA AND THE BROKEN HEART (HC) 0590417266 ANGELA, PRIVATE CITIZEN (HC) 0590443046 ANNA PAVLOVA BALLET'S FIRST WORLD S TAR (HC) 0590478699 AS LONG AS THE RIVERS FLOW (HC) 0590298798 AUTUMN LEAVES (HC) 059022221X BABCOCK (HC) 0590443755 BACKYARD BEAR (HC) 0590601342 BAD GIRLS (HC) 0590601369 BAD, BADDER, BADDEST (HC) 0590427296 BATTER UP! (HC) 0590405373 BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (HC) 0590430211 BEYOND THE CELLAR DOOR (HC) 059041707X BIG AND LITTLE (HC) 0590426222 BIG SARAH'S LITTLE BOOTS (HC) 0590405527 BLACK SNOWMAN, THE (HC) 0590427709 BLITZCAT (HC) 0590433091 BLOODING, THE (HC) 0590601970 BLUE AND THE GRAY, THE (HC) 0590434489 BLUE SKYE (HC) 0590411578 BOATS (HC) 0590407104 BORN INTO LIGHT (HC) 059041237X BORN TO RUN: A RACEHORSE GROWS UP ( HC) 059046843X BOSSY GALLITO, THE (HC) 0590456687 BOTH SIDES NOW (HC) 0590461680 BOY WHO SWALLOWED SNAKES, THE (HC) 0590448161 BSC #01 : KRISTY'S GREAT IDEA (HC) 0439399327 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS #3 THAT’S NO PUDDLE THAT'S ANGELA 0439487196 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS THE EMPEROR OF HOVERBOARD PARK 0439399645 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS DEADLY DREAMS DOCTOR DAMAGE 0439375622 -

Joni Mitchell," 1966-74

"All Pink and Clean and Full of Wonder?" Gendering "Joni Mitchell," 1966-74 Stuart Henderson Just before our love got lost you said: "I am as constant as a northern star." And I said: "Constantly in the darkness - Where 5 that at? Ifyou want me I'll be in the bar. " - "A Case of You," 1971 Joni Mitchell has always been difficult to categorize. A folksinger, a poet, a wife, a Canadian, a mother, a party girl, a rock star, a hermit, a jazz singer, a hippie, a painter: any or all of these descriptions could apply at any given time. Moreover, her musicianship, at once reminiscent of jazz, folk, blues, rock 'n' roll, even torch songs, has never lent itself to easy categorization. Through each successive stage of her career, her songwriting has grown ever more sincere and ever less predictable; she has, at every turn, re-figured her public persona, belied expectations, confounded those fans and critics who thought they knew who she was. And it has always been precisely here, between observers' expec- tations and her performance, that we find contested terrain. At stake in the late 1960s and early 1970s was the central concern for both the artist and her audience that "Joni Mitchell" was a stable identity which could be categorized, recognized, and understood. What came across as insta- bility to her fans and observers was born of Mitchell's view that the honest reflection of growth and transformation is the basic necessity of artistic expres- sion. As she explained in 1979: You have two options. -

Midtown Coffeehouse Alumni Hall Thursdays Spring 2009 Schedule 8:00Pm

Midtown Coffeehouse Alumni Hall Thursdays Spring 2009 Schedule 8:00pm Led by coordinator of jazz studies area Jamie Begian, the January 29 group features alumni Jonathan Blanck on tenor saxophone, WCSU Jazz Quartet Jamie Begian on guitar, alumni/faculty Chris DeAngelis on bass and alumni Tim Walsh on drums. A program of all- Jazz original music is planned with each member of the band contributing 1 composition. A unique and charismatic singer and songwriter, Lara Herscovitch is "...a breath of fresh air in the acoustic world." - February 5 BestFemaleMusicians.com It's about music. Great music. Smart and soulful music. Highly original acoustic / folk flavored with pop Lara Herscovitch and Latin/world styles. Regardless of which song or which melding of styles, listeners, fans and friends agree: Lara is a true original Acoustic/Folk/Pop/Latin and a gem. www.laramarecords.com/home.html February 12 The Parallel Fifths is an all male a capella group, com- prised of both music and non music majors. They travel The Parallel Fifths to grade schools to perform and also have performed with campus co-ed a capella group PIBE. All Male A Capella SPECIAL Co-Sponsored by the Gay Straight Alliance OPENING ACT Tim Walsh is an accomplished instrumentalist, singer, composer, producer, engineer, and teacher. His first solo album, 'Art For Sale' was a collection of songs in various styles - jazz, pop, rock, etc... Artists like Joni Mitchell, who February 19 tend to write about self reflection, were a strong influence for this record. His performance is very much like storytelling, imagery is created in each Tim Walsh song granting an emotional connection to the listener. -

Making the Transition from Outside to In-House Counsel Bethany L

Both Sides Now: Making the Transition from Outside to In-House Counsel Bethany L. Appleby & Gary R. Batenhorst I. Introduction Many in-house lawyers for franchise companies began their careers at law firms where they gained experience representing these same franchise companies. For a vari- ety of reasons, lawyers at various stages of their careers may find it more appealing to move to an in-house posi- tion. In this article, two long-time members of the ABA Forum on Franchising, who have worked both in-house and for law firms, discuss the differences between work- Ms. Appleby ing for franchised companies directly as opposed to rep- resenting these companies at law firms. Although most of the discussion in this article focuses on in-house law departments for franchisors, many of the issues dis- cussed also are relevant for in-house lawyers working in the law department of a multi-unit franchisee, including those with franchises in multiple concepts. II. Backgrounds of the Authors Mr. Batenhorst Bethany Appleby received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale University, magna cum laude, and graduated with highest honors from The University of Connecticut School of Law. Shortly after finishing law school, she joined the New Haven office of Wiggin and Dana LLP, where she eventually became a litigation partner and co-chaired the firm’s Franchise and Distribution Prac- tice Group. After almost twenty years of representing the Subway® restaurant franchisor in litigation, arbitration, and other matters as outside counsel, she Bethany L. Appleby ([email protected]) is a member of Appleby & Corcoran, LLC, in New Haven, Connecticut, and focuses her practice on franchise and business law litigation. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting 1000 (5) CALL TO ORDER Chairman Sam Petrovich Moment of Silence Vice-Chairman Nick Taylor Pledge of Allegiance Chairman Sam Petrovich 1005 (5) Commission Introduction Chairman Sam Petrovich 1010 (3) Oath of Office MG Mark Schindler Robert Forbes- AMVETS 1013 (3) Approval of 4 December meeting minutes REQUIRES A VOTE 1016 (10) DMVA Military Update MG Mark Schindler 1026 (15) VISN 4 Mr. Tim Liezert OLD BUSINESS NEW BUSINESS 1041 (5) DMVA, Policy, Planning & Legislative Affairs Mr. Seth Benge 1046 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Veterans Homes Mr. Rich Adams 1056 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Programs, Initiatives, Reintegration and Outreach (PIRO) Mr. Joel Mutschler SC 1106 (4) Approval of Programs Report (Report provided by DMVA) REQUIRES A VOTE 1110 (5) Act 66 Committee report Mr. Anthony Jorgenson 1115 (5) RETX Committee report Mr. Justin Slep 1120 (5) Legislative Committee report Chairman Sam Petrovich 1125 (5) Pensions & Relief/Grave markings Committee report Ms. Connie Snavely 1135 (10) Member-at-Large Committee Chairman Sam Petrovich 1145 (10) Good of the Order Chairman Sam Petrovich 1155 (5) Next Meeting: April 2, 2021 Webex Virtual 1200 ADJOURNMENT Chairman Sam Petrovich RETIRING OF COLORS Chairman Sam Petrovich State Veterans Commission Meeting Minutes December 4, 2020 10:00 AM to 11:48 AM Webex Video Teleconference Call to Order Chairman Samuel Petrovich The Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission (SVC) meeting was called to order at 10:00 AM by Chairman Samuel Petrovich. Moment of Silence and Pledge of Allegiance The meeting was opened with a moment of silence for the upcoming 79th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance led by Chairman Samuel Petrovich.